The bitter, colossal Battle of Stalingrad was the key turning point of World War II, paving the way for the eventual defeat of Nazi Germany.

Five months, one week, and three days. Lasting from August 1942 to February 1943, the Battle of Stalingrad was the largest battle of World War II — and in the history of warfare. Millions were killed, wounded, missing, or captured in what was perhaps the most brutal battle in modern history.

A grisly monument to the human capacity for violence and survival, the Battle of Stalingrad was marked by massive civilian losses, the executions of retreating soldiers by their own commanders, and even alleged cannibalism.

Historians estimate about 1.1 million Soviet soldiers were killed, missing, or wounded at Stalingrad, in addition to thousands of perished civilians. Axis casualty estimates range between 400,000 to as many as 800,000 killed, missing, or wounded.

This astounding figure means Soviet casualties at this single battle represented nearly 3 percent of total worldwide casualties from the entire war. More Soviets died in this single battle than the number of Americans who died in all of World War II.

Operation Barbarossa

Leading up to the Battle of Stalingrad, the German Wehrmacht had already suffered multiple setbacks in Russia. Germany had launched Operation Barbarossa, its ill-fated invasion of the Soviet Union, in June 1941. Dispatching some 3 or 4 million soldiers to the Eastern Front, Adolf Hitler hoped for a rapid victory.

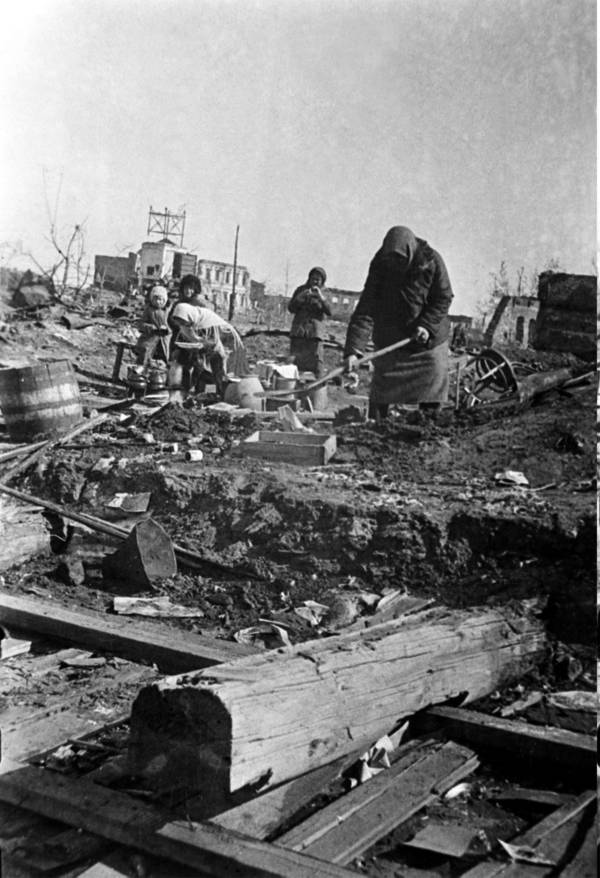

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone/Getty ImagesThe Battle of Stalingrad resulted in over a million Soviet soldier and civilian casualties.

It was an all-out effort to crush the Soviet threat by capturing Ukraine to the south, the city of Leningrad — present-day Saint Petersburg — to the north, and the capital city of Moscow.

Despite initial successes, the Nazi war machine was stopped mere miles away from Moscow. Bogged down by dogged Soviet resistance and the brutal Russian winter, the Germans were eventually pushed back by a Soviet counteroffensive. The operation was a failure. By the spring of 1942, however, Hitler was ready to try again.

Operation Case Blue: Setting Sights On Stalingrad

In April's Directive No. 41, following up on what he called a "great defensive success," Hitler wrote: "[The Soviet Union] has expended during the winter the bulk of reserves intended for later operations. As soon as the weather and the state of the terrain allows, we must seize the initiative again, and through the superiority of German leadership and the German soldier force our will upon the enemy."

Wikimedia CommonsAdolf Hitler in 1937.

In the order, Hitler added that "every effort will be made to reach Stalingrad itself, or at least to bring the city under fire from heavy artillery so that it may no longer be of any use as an industrial or communications center."

These directives resulted in Operation Case Blue: the summer 1942 Nazi offensive tasked with seizing Soviet oil fields in the Caucasus, as well as the industrial city of Stalingrad in the Soviet Union's southeast.

Unlike Barbarossa a year earlier, whose aim was to wipe out the Soviet Union's army and eradicate its Jewish and other minority populations city by city and village by village, Hitler's aim with Stalingrad was to crush the Soviets economically.

The city of Stalingrad, which today is called Volgograd, was massively important to the USSR's economy and war strategy. It was one of the country's most important industrial centers, producing equipment and large amounts of ammunition. It also controlled the Volga River, which was an important shipping route to move equipment and supplies from the denser and more economically prosperous west to the less populated but resource-rich east.

More importantly, Stalingrad was named after the ruthless Soviet leader himself, and for this reason alone became a key target. Hitler was obsessed with occupying the Soviet dictator's namesake, and Joseph Stalin was equally fanatical about not letting it fall into German hands.

Prelude To The Battle Of Stalingrad

During Operation Barbarossa, the Axis powers had attempted several large encircling movements against the Soviets, with early and lethal success. The Soviets, for their part, had eventually learned to counter these efforts and had become adept at evacuations and orderly troop placement to avoid being surrounded.

Sovfoto/UIG/Getty ImagesRed Army soldier aiming his machine gun in a ruined building.

Nonetheless, Hitler personally intervened to order a large encircling capture of Stalingrad, intent on claiming ownership of the city. From the west, Gen. Friedrich Paulus approached with his Sixth Army of 330,000 men. From the south, on Hitler's orders to divert from its original mission, Gen. Hermann Hoth's Fourth Panzer Army formed the other arm of the attack.

Meanwhile, Soviet commanders prepared by evacuating civilians and beginning to arrange their troops for a strategic retreat that would avoid a disastrous encirclement, as they had learned to do successfully in the previous year.

With an enormous land mass stretching thousands of miles behind their front lines, this strategy of making a gradual retreat east had been a key part of Russia's success a year earlier.

"Not One Step Back"

But Stalin's plans changed. In July 1942, he issued Order No. 227, commanding his troops to take "not one step back," instructing army commanders to "decisively eradicate retreat attitude in the troops." The Red Army wouldn't back down from the Germans' offensive. It would stand and fight.

To make matters worse, he also canceled the evacuation of civilians, forcing them to stay in Stalingrad and fight alongside the soldiers. It is alleged that Stalin believed Red Army soldiers would fight harder if civilians were forced to stay, committing more to battle than they would if they were only protecting empty buildings.

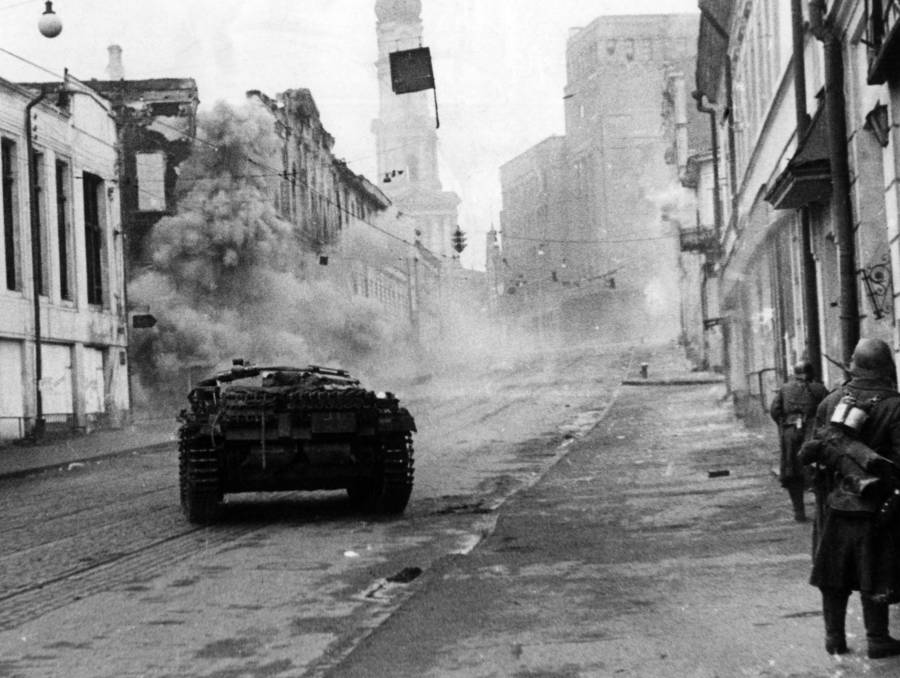

The initial German attack on Stalingrad caught the Soviet forces off guard, as they had been expecting the Nazis to remain focused on Moscow. The German war machine continued to advance rapidly and by August, Gen. Paulus had reached Stalingrad's suburbs.

The Axis armies proceeded to level the city with vicious artillery and aircraft bombing, killing thousands and making the rubble-strewn ruins impassable by tanks.

As a response, the Soviet 62nd Army fell back into the city center and prepared to make its stand against the German infantry. Clinging to the western bank of the Volga River, the Soviets' only resupply option were barges crossing the water from the east.

Red Army soldier Konstantin Duvanov, 19 years old at the time, recalled years later the scenes of death on the river.

"Everything was on fire," said Duvanov. "The bank of the river was covered in dead fish mixed with human heads, arms, and legs, all lying on the beach. They were the remains of people who were being evacuated across the Volga, when they were bombed."

Brutality On Both Sides

By September, the Soviet and Nazi forces were engaged in bitter close-quarters combat for Stalingrad's streets, houses, factories, and even individual rooms.

And it looked like the Germans had the upper hand. By the time Soviet Gen. Vasily Chuikov arrived to take command, the situation was turning increasingly desperate for the Soviets. Their only option was to make a last stand in the city to buy time for a Soviet counterattack.

Considering their dire situation, and frustrated that three of his deputies had fled to save their own lives, Chuikov chose the most brutal methods imaginable to defend the city. "We immediately began to take the harshest possible actions against cowardice," he later wrote.

"On the 14th I shot the commander and commissar of one regiment, and a short while later, I shot two brigade commanders and their commissars."

Although this tactic was an element of the Soviet method, it was the Nazi brutalities which contributed to the Soviets' stubborn defense of Stalingrad. German historian Jochen Hellbeck writes that the number of Soviet soldiers shot and killed by their own commanders due to cowardice has been vastly exaggerated.

Instead, Hellbeck quotes legendary Soviet sniper Vasily Zaytsev, who said that the sight of "the young girls, the children, who hang from the trees in the park..." is what truly motivated the Soviet forces.

Another Soviet soldier recalled a fallen peer "whose skin and fingernails on his right hand had been completely torn off. The eyes had been burnt out and he had a wound on his left temple made by a red-hot piece of iron. The right half of his face had been covered with a flammable liquid and ignited."

Heinrich Hoffmann/Ullstein Bild/Getty ImagesSoldiers hunkered down inside their communications post during the battle.

The Soviets' Last Stand At The Battle Of Stalingrad

By October 1942, Soviet defenses were on the brink of collapse. The Soviet position was so desperate that the soldiers had their backs literally up against the river.

By this point, German machine gunners could actually hit the resupply barges that were crossing the water. Most of Stalingrad was now under German control, and it looked like the battle was about to be over.

But in November, the Soviets' fortunes began to turn. German morale was evaporating due to increasing losses, physical exhaustion, and the approach of the Russian winter. The Soviet forces began a decisive counteroffensive to liberate the city.

On November 19, following a plan created by famed Soviet Gen. Georgy Zhukov, the Soviets launched Operation Uranus to liberate the city. Zhukov masterminded the Red Army attack from both sides of the German attack line with 500,000 Soviet troops, 900 tanks, and 1,400 aircraft.

The counteroffensive converged three days later at the town Kalach to the west of Stalingrad, cutting off the Nazi supply routes and trapping General Paulus and his 300,000 men in the city.

Hitler's Refusal To Retreat

Surrounded inside Stalingrad, Germany's Sixth Army faced atrocious conditions. Against the advice of his commanders, Hitler ordered Gen. Paulus to hold his army's position at all costs.

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone/Getty ImagesGen. Friedrich Paulus of Germany was found in an emaciated state after the Nazis finally surrendered.

Paulus was forbidden from trying to fight his way west and out of the city, and with no land passage available, his soldiers had to be resupplied by air drops from the German Luftwaffe.

As winter set in, the Germans inside Stalingrad were freezing to death, running out of supplies, and starving on short rations. A typhus epidemic hit, with no medications available. Stories of cannibalism began to spread from the city.

In December, a rescue attempt was mounted from outside the city. But rather than a two-pronged attack, Hitler sent Field Marshall Erich von Manstein, one of Germany's most brilliant commanders, to fight his way into Stalingrad while Paulus remained fixed in his position within the city. It was an effort dubbed Operation Winter Storm.

The German Surrender

By the end, the German 6th Army had been trapped in the battle of Stalingrad for almost three months facing disease and starvation and low on ammunition, and there was little left to do than die within the city. About 45,000 men had already been captured, and another 250,000 were dead inside and around the city.

Rescue attempts had been defeated by the Soviets, and the Luftwaffe, which was dropping supplies by air to provide the only food available to the trapped Germans, could only supply one third of what was needed.

On Jan. 7, 1943, the Soviets offered a deal to German Gen. Friedrich Paulus: If he surrendered within 24 hours, his soldiers would be safe, fed, and given the medical care they needed. But Paulus, on orders from Hitler himself, refused. The Germans believed that by prolonging the Battle of Stalingrad, the Germans would weaken the Soviets' efforts on the rest of the Eastern Front.

Days later, Hitler doubled down on Paulus, sending him word that he had been promoted to Field Marshal, and reminding him that no one of that high rank had ever surrendered. But the warning didn't matter — Paulus officially surrendered the next day.

The Defeated General

When Soviet officers entered Stalingrad after the German surrender, they found Paulus "seemed to have lost all his courage." Around him "filth and human excrement and who knows what else was piled up waist-high. It stank beyond belief," according to Maj. Anatoly Soldatov.

Still, Paulus may have been one of the most fortunate of the German survivors of Stalingrad.

Some estimate that more than 90 percent of the surrendered Germans would not survive Soviet captivity for long. Of the 330,000 who had occupied Stalingrad, barely 5,000 survived the war.

Paulus and his second-in-command, Gen. Walther von Seydlitz-Kurzbach, however, found a way to stay alive. They cooperated with Soviet officials through the "Free Germany Committee," a propaganda group composed of war prisoners who broadcast anti-Nazi messages. Paulus and Seydlitz would go on to become highly vocal critics of the Nazis for the rest of the war.

Corbis/Getty ImagesGerman prisoners are marched through the snowy streets of battered Stalingrad after their defeat.

The Aftermath Of The Battle Of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad marked the turning point of World War II. In the end, it was the fight against the Soviets, not against western Europe, that led to the Nazis' defeat. After the Battle of Stalingrad, even the tone of the Nazi propaganda changed. The loss had been so devastating that it could not be denied, and it was the first time that Hitler publicly acknowledged defeat.

Joseph Goebbels, Hitler's propaganda specialist, gave a speech after the battle stressing the mortal danger that Germany faced, and calling for total warfare on the Eastern front. Thereafter, they launched Operation Citadel, attempting to destroy the Red Army at the Battle of Kursk, but they would fail yet again.

This time, the Nazis would not recover.

Next, take a look at 54 photos of the Battle of the Bulge that capture the Nazis' last-ditch counteroffensive. Then learn about the Battle of Verdun, the longest battle of World War I.