When a fire erupted inside the coal mine in Centralia, residents thought it would quickly burn out on its own. But the blaze is still going six decades later and the state has given up on trying to fight it.

Peter & Laila/FlickrThe underground fire in Centralia, Pennsylvania has been burning for 60 years, turning this once-vibrant community into a ghost town.

Centralia, Pennsylvania once boasted 14 active coal mines and 2,500 residents in the early 20th century. But by the 1960s, its boomtown heyday had passed and most of its mines were abandoned. Still, over 1,000 people called it home, and Centralia was far from dying — until a coal mine fire began below.

In 1962, a fire started in a landfill and spread to the labyrinthine coal tunnels that miners dug thousands of feet below the surface. And despite repeated attempts to extinguish the flames, the fire caught a coal seam and still burns to this day.

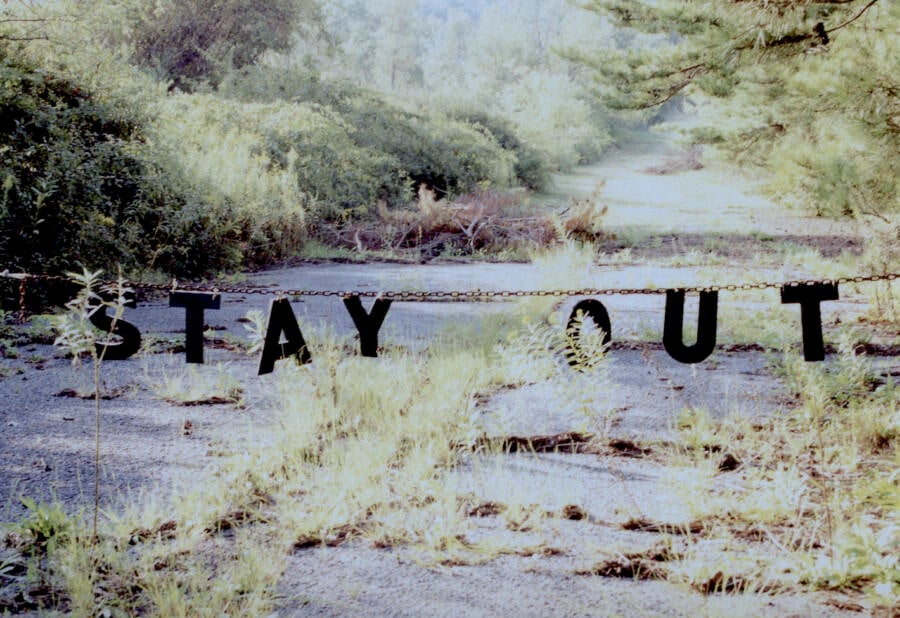

In the 1980s, Pennsylvania ordered everyone out to raze the town’s buildings and the federal government even revoked its ZIP code. Only six homes remain, occupied by the town’s final holdouts.

Wikimedia CommonsSmoke rises from the ground near the original landfill site, in Centralia, Pennsylvania.

But the fire that burns beneath the surface continues to spew poisonous smoke into the air through hundreds of fissures while the ground is in constant danger of collapsing.

Read the incredible story of this abandoned town in Pennsylvania that has been on fire for 60 years — and is the real Silent Hill town.

The Centralia, Pennsylvania Fire Starts In A Landfill

Bettmann/Getty ImagesOne of the ventilation shafts installed to keep gas from building up under Centralia, August 27, 1981.

In May of 1962, the town council of Centralia, Pennsylvania met to discuss the new landfill.

Earlier in the year, Centralia had built a 50-foot-deep pit that covered an area about half the size of a football field to deal with the town’s problem with illegal dumping. However, the landfill was getting full and needed clearing before the town’s annual Memorial Day celebration.

At the meeting, council members proposed a seemingly obvious solution: burning out the landfill.

At first, it seemed to work. The fire department lined the pit with an incombustible material to contain the fire, which they lit on the night of May 27, 1962. After the landfill’s contents were ash, they doused the remaining embers with water.

However, two days later, residents again saw flames. Then again a week later on June 4. Centralia firefighters were baffled as to where the recurring fire was coming from. They used bulldozers and rakes to stir up the remains of the burned garbage and locate the concealed flames.

Finally, they discovered the cause.

The Fire Spreads Through Miles Of Coal Mines

Travis Goodspeed/FlickrCoal tunnels zigzag underneath Centralia, Pennsylvania, giving the fire a near infinite source of fuel.

At the bottom of Centralia’s trash pit, next to the north wall, was a hole 15-feet wide and several feet deep. Waste had concealed the gap. As a result, it had not been filled with fire-retardant material.

And the hole provided a direct pathway to the labyrinth of old coal mines over which Centralia was built.

Soon, residents began complaining of foul odors entering their homes and businesses, and they noted wisps of smoke coming out of the ground around the landfill.

The town council brought in a mine inspector to check the smoke, who determined that the levels of carbon monoxide in them were indeed indicative of a mine fire. They sent a letter to the Lehigh Valley Coal Company (LVCC) stating that a “fire of unknown origin” was burning under their town.

The council, the LVCC, and the Susquehanna Coal Company, which owned the coal mine in which the fire was now burning, met to discuss ending the fire as quickly and cost-effectively as possible. But before they reached a decision, sensors detected lethal levels of carbon monoxide seeping from the mine, and all Centralia-area mines were immediately shut down.

Trying — And Failing — To Put Out The Centralia, PA Fire

Cole Young/FlickrThe main highway running through Centralia, Route 61, has had to be rerouted. The former road is cracked and broken and regularly spews clouds of smoke from the fires burning beneath it.

The commonwealth of Pennsylvania tried to stop the spreading of the Centralia fire several times, but all attempts were unsuccessful.

The first project involved excavating beneath Centralia. Pennsylvania authorities planned to dig out the trenches to expose the flames so they could extinguish them. However, the plan’s architects underestimated the amount of earth that would have to be excavated by more than half and eventually ran out of funding.

The second plan involved flushing out the fire by using a mixture of crushed rock and water. But uncommonly low temperatures at the time caused the water lines to freeze, as well as the stone grinding machine.

The company also worried that the amount of mixture they possessed could not completely fill the warren of mines. So they elected to fill them only halfway, leaving ample room for the flames to move.

Eventually, their project also ran out of funding after going almost $20,000 over budget. By then, the fire had spread by 700 feet.

But that didn’t stop people from going about their daily lives, living above the hot, smoking ground. The town population was still about 1,000 by the 1980s, and residents enjoyed growing tomatoes in the midwinter and not having to shovel their sidewalks when it snowed.

In 2006, Lamar Mervine, the then-90-year-old mayor of Centralia, said people learned to live with it. “We’d had other fires before, and they’d always burned out. This one didn’t,” he said.

Why Some Residents Have Fought To Stay In This Pennsylvania Ghost Town

Michael Brennan/Getty ImagesFormer Centralia Mayor Lamar Mervine, pictured atop a smouldering hill in the burning Pennsylvania town, March 13, 2000.

Twenty years after the fire started, however, Centralia, Pennsylvania began to feel the effects of its eternal flame underground. Residents started passing out in their homes from carbon monoxide poisoning. The trees began to die, and the ground turned to ash. Roads and sidewalks began to buckle.

The real turning point came on Valentine’s Day in 1981, when a sinkhole opened up underneath 12-year-old Todd Domboski’s feet. The ground was searing and the sinkhole was 150-feet deep. He only survived because he was able to grab ahold of an exposed tree root before his cousin arrived to pull him out.

By 1983, Pennsylvania had spent more than $7 million trying to put out the fire with no success. A child had almost died. It was time to abandon the town. That year, the federal government appropriated $42 million to purchase Centralia, demolish the buildings, and relocate the residents.

But not everybody wanted to leave. And for the next ten years, legal battles and personal arguments between neighbors became the norm. The local newspaper even published a weekly list of who was leaving. Finally, Pennsylvania invoked eminent domain in 1993, by which point only 63 residents remained. Officially, they became squatters in houses they had owned for decades.

Even so, that didn’t put an end to the town. It still had a council and a mayor, and it paid its bills. And over the next two decades, residents fought hard to stay legally.

Sue/FlickrSmoke from the smoldering fire in Centralia.

In 2013, the remaining residents — then fewer than 10 — won a settlement against the state. Each was awarded $349,500 and ownership of their properties until they die, at which point, Pennsylvania will seize the land and finally demolish what structures remain.

Mervine recalled choosing to stay with his wife, even when offered a bailout. “I remember when the state came and said they wanted our house,” he said. “She took one look at that man and said, ‘They’re not getting it.'”

“This is the only home I’ve ever owned, and I want to keep it,” he said. He died in 2010 at the age of 93, still illegally squatting in his childhood home. It was the last remaining building on what was once a three-block-long stretch of row houses.

The Legacy Of Centralia

Fewer than five people still live in Centralia. Experts estimate there is enough coal underneath Centralia to fuel the fire for another 250 years.

But the story and infrastructure of the town has provided its own kind of fuel for creative endeavors. The real Silent Hill town that inspired the 2006 horror film is this abandoned Pennsylvania town. Though there is no real Silent Hill town, the movie used the setting and what happened to Centralia as part of its plot.

R. Miller/FlickrCentralia, Pennsylvania’s graffiti highway in 2015.

And the abandoned Route 61 that leads into the town center was also given new life for many years. Artists transformed this three-quarter-mile stretch into a local roadside attraction known as the “graffiti highway.”

Even as the pavement cracked and smoked, people came from around the country to leave their mark. By the time a private mining company purchased the land and filled the road with dirt in 2020, nearly the entire surface was covered by spray paint.

Today, Centralia, Pennsylvania is better known as a tourist attraction for people looking to glimpse one of the plumes of noxious smoke rising from beneath the earth. The surrounding forest has crept in where a once-thriving main street was lined with long-demolished stores.

“People have called it a ghost town, but I look at it as a town that’s now full of trees instead of people,” resident John Comarnisky said in 2008.

“And truth is, I’d rather have trees than people.”

After learning about Centralia, Pennsylvania, read about the most polluted ghost towns in America. Then, read about the world’s most mystifying ghost towns.