Desperate to end a dry spell, the San Diego council hired self-proclaimed "moisture accelerator" Charles Hatfield to fill the Morena reservoir. He did much, much, more than that.

In 1915, San Diego hired Charles Hatfield, a man who claimed he could make it rain to end a devastating drought. “I do not make rain,” Hatfield insisted, “That would be an absurd claim. I simply attract clouds, and they do the rest.”

Indeed, clouds were attracted to Hatfield, perhaps too much so. Instead of bringing rain, Hatfield conjured epic floods that turned deadly.

Charles Hatfield’s Background

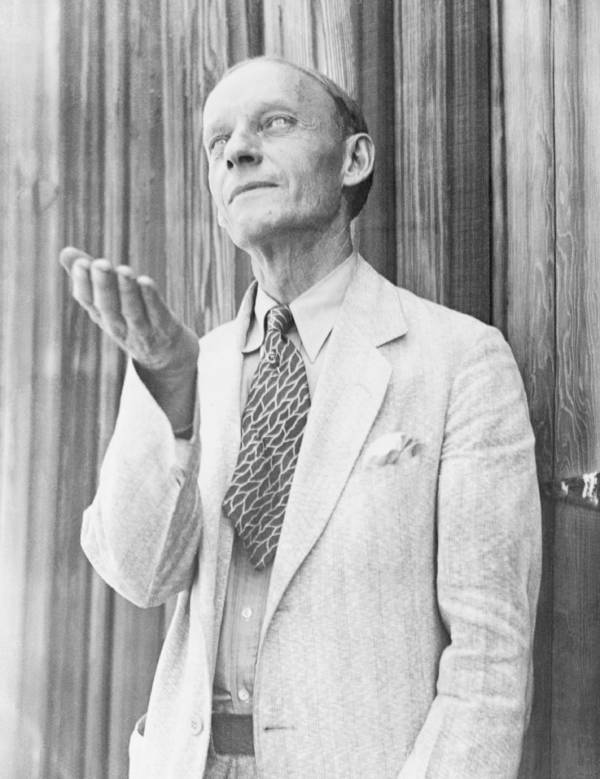

Bettman/GettyCharles Hatfield, the rainmaker, holds his hand palm-up, perhaps conjuring some droplets.

Before summoning the floods, Charles Mallory Hatfield was but a humble sewing machine salesman. But his earnest Quaker background would help him to garner trusting clients in his rainmaking business.

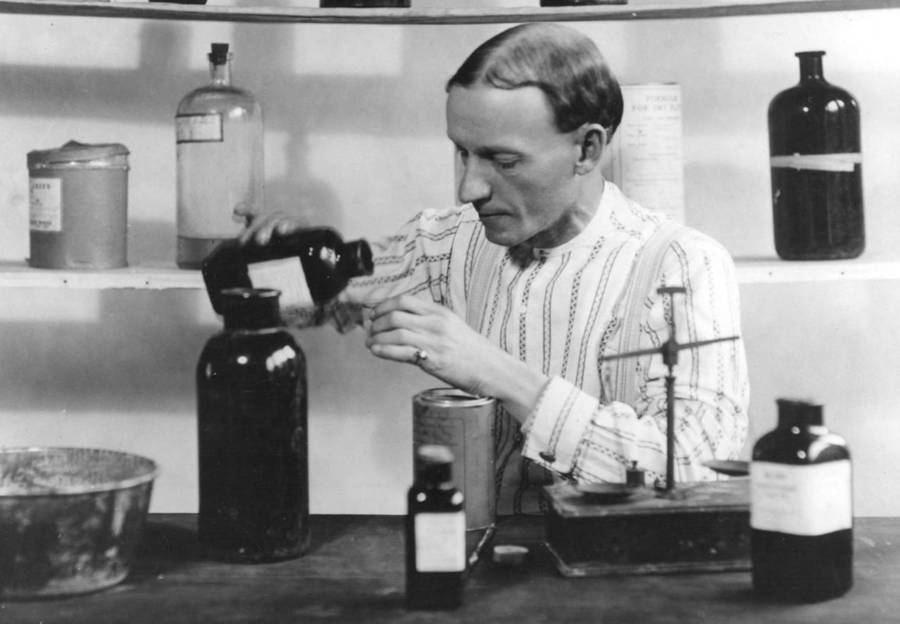

In his spare time, Hatfield studied pluviculture and mixed his own methods for rain production. By 1902, he had created a mixture of 23 chemicals in evaporating tanks which, he claimed, attracted rain. Charles Hatfield thus dubbed himself a “moisture accelerator.”

The term “rainmaker” may sound as though it came straight from the ancient world, and in the 20th century, many salesmen like Hatfield based their trade on a sort of pseudoscience, not unlike the magic of old spells.

Instead of appealing to the gods with secret prayers and special rituals, though, Hatfield believed he could instigate rainfall by evaporating mixtures of dynamite, nitroglycerin, and other ingredients – he took the exact formula with him to his grave – into the air from towers.

Hatfield’s process seems to be an early form of “cloud seeding,” or the process of sending chemicals into the air that will react with elements in the cloud to produce particles of precipitation. Although this is certainly a more scientific-sounding process than “rainmaking,” experts today still debate the effectiveness of cloud-seeding.

San Diego Public LibraryCharles Hatfield shown mixing up his secret rain-making formula in 1922.

Hatfield’s main selling point was that he wouldn’t charge people until he had produced results. When asked by one reporter if he was really going to make it rain he replied, “I certainly will, or it won’t cost the people a cent.”

In 1904, the Quaker from Kansas began by charging clients – mostly small farmers — $50 for his services, but word of his skills soon spread after a series of successful rainfalls. A year later, he upped his price to $1,000 per inch of rain.

San Diego’s Great Drought

San Diego had long had problems with water supply. Since the city has little in the way of natural water sources, it relies heavily on reservoirs, which run dry during an extreme drought. This is exactly what had happened in late 1915 after weeks without rain and consequently brought the desperate San Diego City Council to turn to Charles Hatfield, despite the protests of one council member who ruled the idea nothing but “foolishness.”

Bettman/GettyCharles Hatfield holding his umbrella.

The 40-year-old rainmaker made a deal with the city in which he would either fill the Morena reservoir or induce between 30-50 cm of rain at the cost of $10,000, to be paid after the showers started, of course. The Council amazingly agreed to the proposal, albeit verbally only, and Hatfield together with his younger brother constructed a tower where he could conduct his secret work.

In early January 1916, it began to rain over San Diego after weeks of drought. The wife of the local dam keeper recalled how on a visit to Hatfield’s tower during the early days of the drizzle she declared, “It’s sure raining now!” to which Charles Hatfield replied, “You haven’t seen anything yet. Wait two weeks and it will really rain.”

And really rain it did.

Visual Studies Workshop/Getty ImagesPortrait of Charles Hatfield and his brother, Paul.

Charles Hatfield’s Flood

At first, San Diegans rejoiced in Charles Hatfield’s fulfillment of his promise, with one newspaper joyfully proclaiming “Rainmaker Hatfield Induces Clouds To Open.” It seemed their prayers had been answered.

But when the rains continued for a week people grew ready for a break. A semi-serious poem beseeched Hatfield to stop, “From Saugus down to San Diego’s Bay, they bless you for the rains of yesterday. But Mister Hatfield, listen now; Make us this vow: Oh, please, kind sir, don’t let it rain on Monday!”

San Diego Historical SocietySan Diego suffered horrendous floods in early 1916.

Joy turned into apprehension and then dismay as the rain turned to storms and water overflowed the reservoirs. By January 27, the floods had destroyed everything in their path. When the “Hatfield Flood” ended, an estimated 30 inches of rain had fallen and around 20 people were killed.

Rather than stick around to collect his fee and “fearful of being lynched by angry farmers,” Hatfield decided to skip town.

Lawsuit, Legacy, And Later Life

The rainmaker did eventually return to try and collect his $10,000 dollars, although the infuriated City Council sent him packing.

When Charles Hatfield decided to sue, one councilman cleverly propositioned that they would pay the rainmaker his money, but on the condition that he also accepted responsibility for creating the floods and pay the city for the damage it caused. Hatfield then decided it would be best to cut his losses and left San Diego behind without his money.

San Diego Historical SocietyMore of the damage caused by “Hatfield’s Flood.”

Although Charles Hatfield’s rainmaking career ended with the Great Depression, which forced him to go back to selling sewing machines, his legend endured in the form of pop culture, books, and songs, and experts still debate his responsibility in the 1916 flood.

Weathermen during Hatfield’s time observed that the rainmaker tended to see to those locations where rain was in the forecast. Hatfield also boasted that he had made it rain more than 500 times, which made most experts wary of his abilities. Charles Hatfield could very well have simply been a great fraud who was even better at forecasting the weather.

After this look at Charles Hatfield, read about San Francisco’s worst natural disaster: the earthquake of 1906. Then, read about the man who thought he could harness the power of orgasms to control the weather.