While we know Dr. Seuss best for his tongue twisters and whimsical characters, the famed children's author actually got his start by drawing some rather controversial ads.

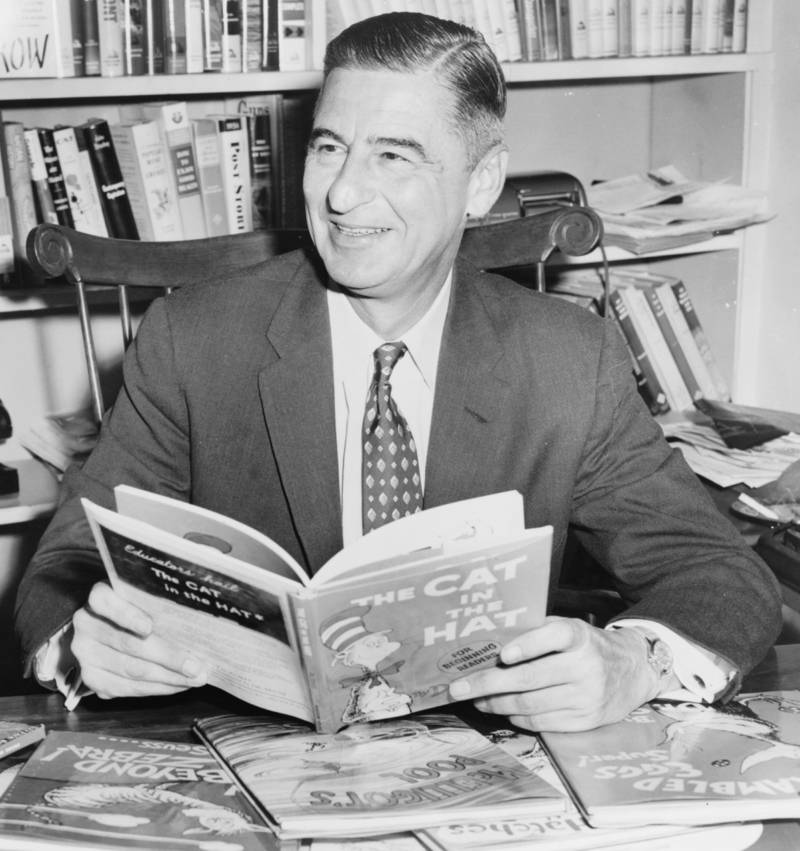

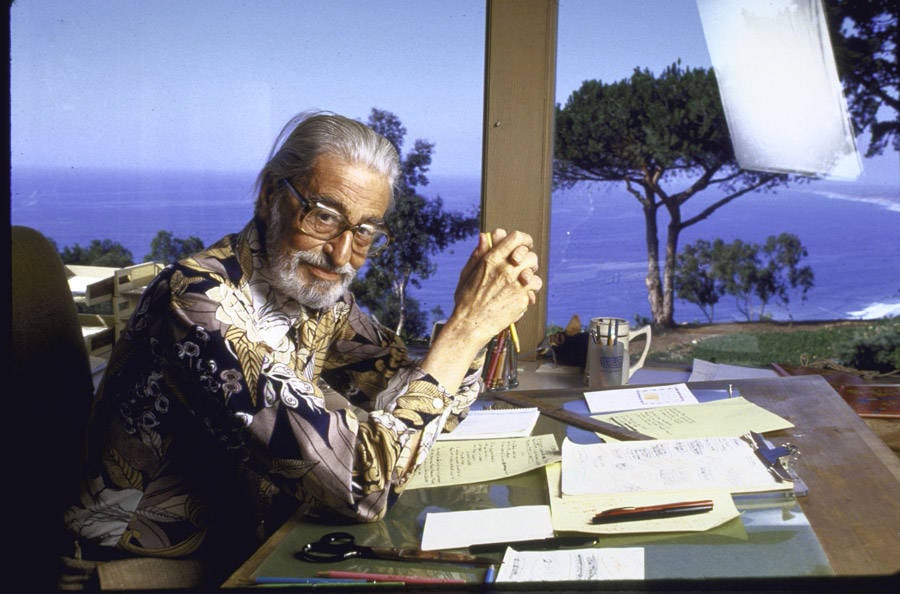

Theodor Geisel. 1957

Even in death, Dr. Seuss continues to entertain millions of children with his stories of whimsical characters and tongue twisters. Though, despite being a household name with over forty books, including The Cat In The Hat and Green Eggs And Ham, fans have been pronouncing his name wrong all these years.

Though Seuss is spelled like Zeus, it is not pronounced like Soose at all. Instead, the Bavarian name is pronounced like Zoice. Seuss was, in fact, the maiden name of his German mother, Henrietta. It was also his middle name. The addition of “Dr”, Theodor Geisel explained, was for his father who wanted him to become a professor.

While it is not exactly a shock that Geisel is one of the biggest selling children’s authors of all time, there are many contradictions about the author. For instance, it may come as a surprise that he had very little do with children until after his success with The Cat In The Hat in 1957.

When asked why he didn’t have children of his own, he quipped, “You make ’em, I’ll amuse ’em.” According to his second wife Audrey, he was slightly afraid of children. But with his success, he’d be forced into the public eye to interact with them. Something he did rather well.

But, the made-up words, the rhyme and rhythm, and tongue twisters of his whimsical stories that his child fans loved so much were often about far deeper political and social themes, particularly in his later books, that often divided adults. Recently his work has come under closer scrutiny revealing a little-known side to Geisel.

His prolific work in advertising, his political cartoons and even some of his books have been labeled sexist, vulgar, and even racist. How can we explain these contradictions? What do they say about the man, the time in which he lived, and the work he left behind?

Childhood Inspiration

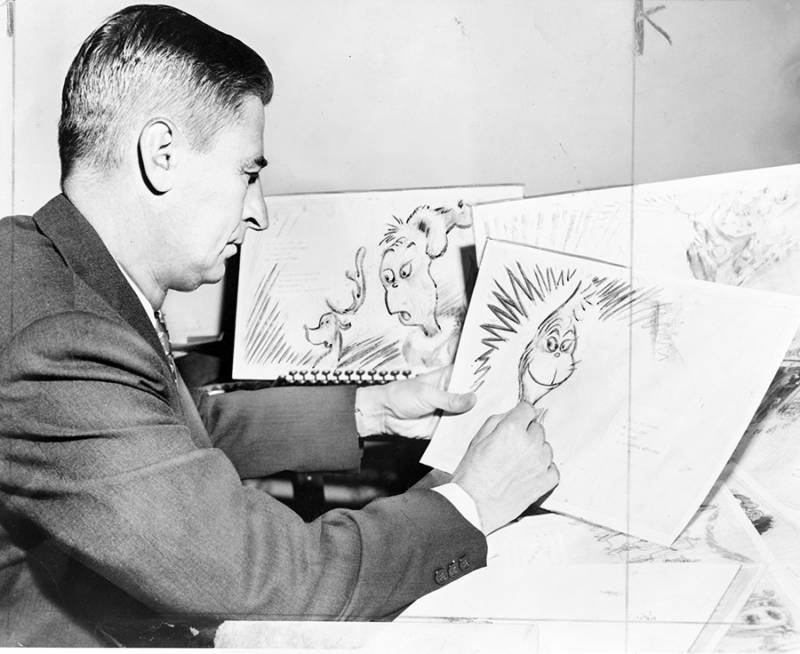

Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty ImagesAmerican writer and cartoonist Dr. Seuss draws the grinch.

Theodor Geisel was born on March 2, 1904. His early childhood was a happy one, and the outlandish tales he wrote as an adult were peppered with many early autobiographical details from his home life in Springfield. Place names, people’s names, and situations formed the basis of some of his wacky and whimsical stories.

Terwilliger and Bickelbaum were not unusual names he dreamt up for his books but borrowed from real-life neighbors he grew up around. And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street is set on the real-life street of the same name that he walked along to school each day, while If I Ran The Zoo, about a boy fantasizing about running his father’s zoo, is based on Springfield Zoo, which his father ended up owning.

There is a bit of his family life in all his books, but Geisel credited his mother for helping develop his signature writing style. “More than anybody else,” Geisel said. “My mother was responsible for the rhythms in which I write.”

In 1921, Geisel went to Dartmouth College in New Hampshire and gravitated to the college humor magazine, Jack-O-Lantern, where he published his first cartoons. By the end of his junior year, his cartoons began to exhibit his trademark combination of humorous words with distinctly quirky drawings. It was also the year he became the magazine’s Editor-in-Chief.

However, during Easter 1925, Geisel and nine others were caught sharing a pint of gin amongst them. They were put on probation for breaking Prohibition laws and Geisel lost his position as Editor-in-Chief. But this didn’t stop him and forced him to use various pseudonyms to get published, under such names as “L. Pasteur” and “Thos. Mott Osbourne”, the name of the warden at the notorious Sing Sing prison.

It was also the first time he used “Seuss.”

“To what extent this corny subterfuge fooled the dean, I never found out,” said Geisel. “But that’s how ‘Seuss’ first came to be used as my signature. The ‘Dr’ was added later on.”

In 1925, he was off to Oxford University to study English Literature, which, he realized, he had limited interest in. Notes were gradually replaced with fantastical drawings.

“As you go through the notebook, there’s a growing incidence of flying cows and strange beasts. And, finally, at the last page of the notebook there are no notes on English literature at all. There are just strange beasts.”

His classmate Helen Palmer convinced him to pursue a career as an illustrator, and after one year at Oxford, he dropped out.

The Controversy Behind Dr. Seuss’ Advertisements And Political Cartoons

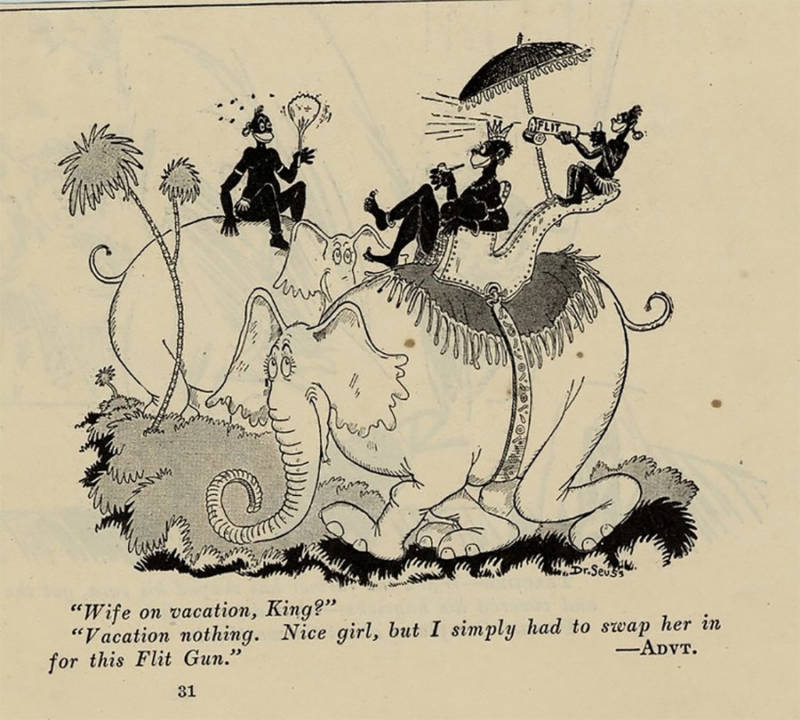

University of California, San Diego, LibraryA Flint cartoon ad from Dr. Seuss.

In 1927, Geisel and Palmer married and then moved to New York. After a year of struggling financially, Geisel got a job with the now-defunct satirical magazine Judge where he started using the pseudonym Dr. Seuss professionally.

About four months into the job, he drew an insecticide gag that changed his life. In it, a knight looks up at a dragon nuzzling him and says, “Darn it, another dragon. And just after I’d sprayed the whole castle with… .? “With what? I wondered. There were two well-known insecticides. One was Flit and one was Fly Tox. So, I tossed a coin. It came up heads, for Flit.”

Before he knew it, Flit had hired him and he captioned his first ad with “Quick Henry, the Flit!” which became a popular catchphrase of its day.

From 1927 through the 1950s, Geisel illustrated campaigns for Flit’s parent company, Standard Oil, followed by ad campaigns for Holly Sugar, Ford, GE, and NBC. Though the advertisements were aimed at adults, some of the characters from these adverts would later reappear in his children’s books.

Other characters were decidedly racist caricatures.

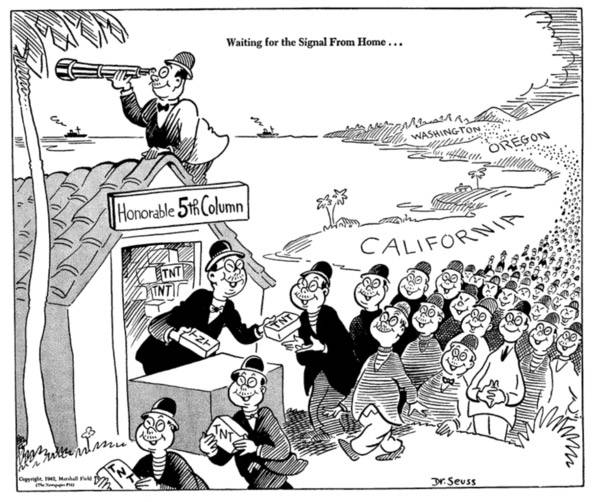

Wikimedia commonsGeisel’s wartime political cartoons often lampooned America’s isolationism before Pearl Harbor.

Adverts for Flit depicted black people as savages with ape-like facial features holding spears or cooking white men in a pot. Arabs are drawn as sultans, camel-riders, or in one ad, as a servant leading a camel carrying a white man. The originality of his zany drawings had not extended to his racial stereotypes, which were views shared by his contemporaries.

From 1940, he drew over 400 political cartoons on World War II for the liberal newspaper PM. But his clever cartoons on Adolf Hitler, fascism, and America’s isolationism before Pearl Harbor, are in today’s light, often overshadowed by some deplorable racial stereotypes.

Though numerous cartoons railed against anti-Semitism, Geisel was not so favorable in his representation of the Japanese. Most notably, Call to Arms depicts Hitler as an almost pleasing caricature and at least recognizable. On the other hand, Hideki Tojo, the Prime Minister, and Supreme Military Leader of Japan is drawn with squinty eyes and buck teeth, an ugly racial stereotype representing all Japanese.

Wikimedia CommonsA Dr. Seuss 1942 cartoon with the caption “Waiting for the Signal from Home.”

While he was a liberal Democrat and passionately opposed fascism, racism, and anti-Semitism, he also initially supported the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

“… right now, when the Japs are planting their hatchets in our skulls, it seems like a hell of a time for us to smile and warble: “Brothers!” It is a rather flabby battle cry. If we want to win, we’ve got to kill Japs, whether it depresses John Haynes Holmes or not. We can get palsy-walsy afterward with those that are left,” he once said.

To some Geisel’s racist stereotyping is viewed as a product of the time. Afterall, World War II was raging and after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, his cartoon’s were more overtly anti-Japanese.

However, according to Ron Lamothe, the filmmaker behind The Political Dr. Seuss, Geisel later regretted his past beliefs and even scanned and amended his earlier works to remove any racist oversights.

In fact, Geisel would later write 1954’s Horton Hears a Who after a trip to Japan, using his story as an allegory for the post-war occupation of the country. He dedicated the book to Mitsugi Nakamura, a Japanese friend and professor.

Crude Jokes And Propaganda: Dr. Seuss’ Time In Hollywood

Getty ImagesA politial cartoon drawn by Theodor Geisel, also known as Dr. Seuss.

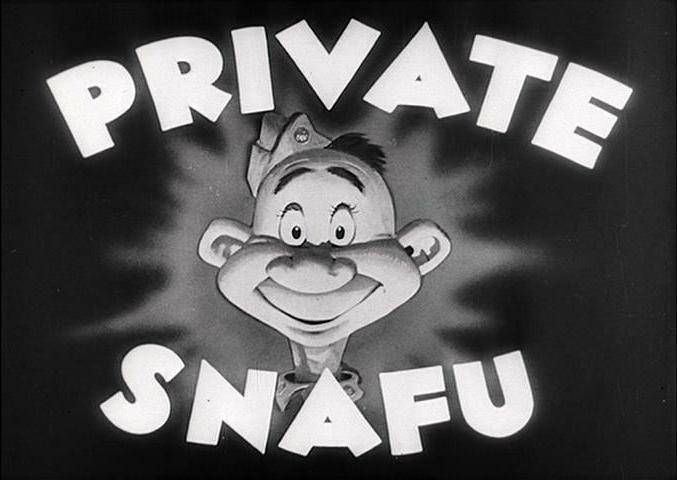

In 1943, Geisel joined the Army and was recruited as a commander into First Motion Picture Unit of the US Airforce in Hollywood. Geisel worked with film director Frank Capra, and animator Chuck Jones, the creator of Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck, to make Private Snafu, a series of animated films aimed to teach basic lessons to GIs through Snafu’s mistakes.

To get the soldiers attention, Geisel used adult humor with a combination of double entendres and visual gags. For instance, in the film entitled Booby Traps, Private Snafu claims that no booby traps will get past him.

“I ain’t no boob and I won’t be trapped!”

But during the harem sequence, the phrase booby trap becomes quite literal. He attempts to hit on a scantily-clad woman. At one point her brasserie drops to reveal two circular bombs instead of breasts.

Wikimedia commonsPrivate Snafu used irreverent humor to teach Army recruits.

In 1945, after the success of Private Snafu, Capra enlisted Geisel to make propaganda films aimed at American soldiers who would be occupying Germany and Japan at war’s end. Both the films Your Job in Germany and Your Job in Japan featured no gags or cartoons. Rather, they delivered a strong message to the occupiers about the Japanese and German people. Though a son of a German, Geisel found himself once again stereotyping an entire people:

“Someday the German people might be cured of their disease. The super race disease. The world conquest disease. But they must prove that they have been cured. Beyond the shadow of a doubt. Before they ever again are allowed to take their place among respectable nations. Until that day we stand guard.”

In 1948, Your Job in Japan was re-edited and repackaged for public consumption winning an Academy Award for Best Documentary:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=czW1IJ-Hd1I

The Children’s Books Of Dr. Seuss

Gene Lester/Getty ImagesAmerican author and illustrator Theodor Geisel, also known as Dr Seuss, sits outdoors talking with a group of children.

During his advertising and Hollywood years, Geisel started writing books. The inspiration behind the first, And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Streetis decidedly Seussian.

In 1936, while on a cruise ship for eight days, the constant, repetitive sound of the ship’s engines became a rhythm in his head. For fun, he added words to the rhythm which formed the rhythmic lines of text in Mulberry Street.

The book, about fabricating stories and letting the imagination run wild, was turned down by twenty-seven publishers. Geisel was about to throw the book away when a chance encounter with an editor on Madison Avenue led to the book being published by Vanguard Press.

“That’s one of the reasons I believe in luck,” Geisel recalled of the encounter. “If I’d been going down the other side of Madison Avenue, I would be in the dry-cleaning business today!”

After his second book, The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, Geisel left Vanguard for Random House and he wrote his first adult book. Titled The Seven Lady Godivas, it was about the exploits of nude sisters.

It tanked. Geisel would not write another adult book for 50 years.

In 1940, Horton Hatches An Egg was the first Dr Seuss book to feature an outright moral. Geisel demonstrated that unlike the Dick and Jane primers that made children wish they had never read, moral tales could be fun.

The book is about Horton the elephant who sits on an abandoned egg for 51 days, rain or shine, while the egg’s mother takes a permanent vacation to Palm Beach. But when the mother decides to return and get Horton off the egg, it hatches and out springs a tiny elephant with bird wings. Many have argued that the story one about ethics, morality, and consequences.

The heart-warming story outsold Geisel’s previous books. But he would not write another for seven years while he worked as a propagandist during World War II.

In 1947, Geisel and his wife Helen moved to La Jolla, where they built a home overlooking the ocean on Mount Soledad. Geisel’s office became a prolific sanctuary where Geisel would write one book per year for a decade.

Some of his finest and most important works were produced in this period.

FlickrA collection of Dr. Seuss books.

In 1954, Geisel reached a turning point in his work. An article in LIFE magazine by writer John Hershey took aim at tepid stories featured in Dick and Jane primers as being responsible for a drop in literacy in the United States. Hershey offered Dr. Seuss books as the solution.

William Spaulding, the director of Houghton Mifflin, read the article and hired Geisel to write a story “that first-graders can’t put down!” Geisel was given one stipulation: he could only use 225 different words from a list of 348. He ended up using 236.

Frustrated with the process, Geisel chose the first two letters that rhymed and created a story around them.

The result was The Cat and the Hat. Geisel did the opposite of Dick and Jane and introduced chaos into the story. The way children really behave.

When the book was published in 1957, it was a huge hit that turned Geisel into a household name. The success inspired Geisel, his wife Helen, and Phyllis Cerf to launch Beginner Books a division at Random House. Titles included Go, Dog. Go!, The Berenstain Bearsseries, and Geisel’s next book, Green Eggs And Ham, written from only fifty words. It soon became his best-selling book of all time.

In 1967, Geisel’s first wife Helen committed suicide. Helen had struggled with partial paralysis from Guillain-Barre syndrome for over a decade, and along with depression from her failing health, she may have suspected her husband was having an affair with their friend, Audrey Stone Dimond.

A year later Dimond would become Geisel’s second wife.

In his later books, Geisel wanted to teach children how to think about important social issues. Yertle the Turtle and The Sneetches discuss issues of dictatorship and anti-Semitism in the wake of World War II. But his most hard-hitting books were The Butter Battle Bookand The Lorax.

Geisel wrote The Lorax after witnessing workmen cutting down trees while holidaying in Kenya. He wrote a story draft in one sitting on a laundry list.

The Lorax tells the story of a repentant industrialist who cut down all the trees and drove away the Lorax, a furry little character that could communicate with the trees. In the end, the ex-industrialist informs the reader that they can reverse the damage by planting more Truffula trees, so “the Lorax/ and all his friends/ may come back.”

Mark Kauffman/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty ImagesTheodore Geisel, also known as Dr. Seuss, at home.

While well-received, The Lorax caused friction with logging communities. The logging communities tried to have the book banned from their local school libraries, while it even made it to the annual list of challenged and banned books of the American Library Association.

The sales of The Lorax were initially slow, but Geisel reasoned that it if you weren’t patronizing and you weren’t false, you could discuss anything with children. He also felt that children were his only hope — adults in his mind were just “obsolete children.”

But as he got older with declining health, he began to face his own mortality, and he once again wrote for adults. His 1986 book, You’re Only Old Once! was based on the indignities of aging and topped the New York Times bestseller list, a far cry from his first adult book, The Seven Lady Godivas. Within a year, over one million copies had been sold.

He followed that up in 1990 with Oh, The Places You’ll Go! which also shot to the top of the New York Times Adult bestseller list. In the book, Geisel talks about the end of life’s journey and then the journey we make beyond that.

Wishing to remain where he worked for so many years, a bed was placed in his studio in La Jolla. On Sept. 24, 1991, the 87-year-old Geisel died from oral cancer in his studio a few feet from his drawing board and the creatures he spent a lifetime making.

Now that you’ve learned about Dr. Seuss, read about the real and horrifying stories behind Disney classics. Then learn about the dark side of beloved children’s books and their authors.