Had he so desired, the "Father of Relativity" could have been Israel's second president.

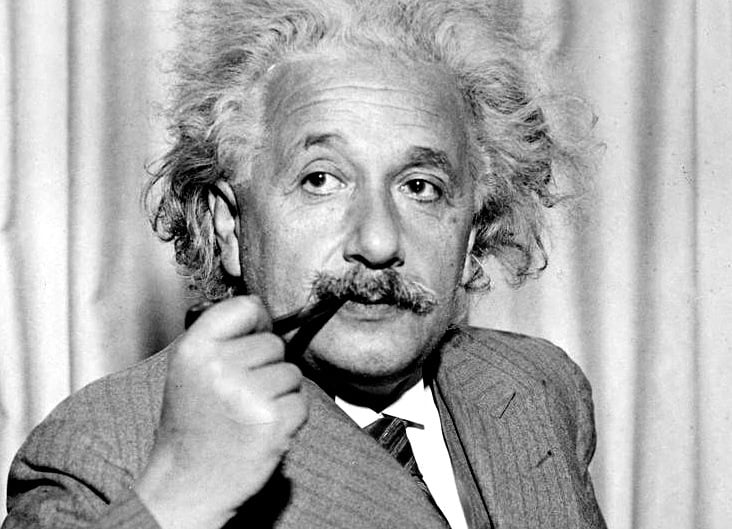

Wikimedia CommonsAlbert Einstein in Princeton, New Jersey, soon after he fled Nazi Germany in 1933.

As a Nobel Prize-winning physicist and the creator of the world’s most famous equation, Albert Einstein had an impressive resume. But there was one notable title he turned down: President of Israel.

Israel’s first president, Chaim Weizmann, said that Einstein was “the greatest Jew alive.” So, upon Weizmann’s death on November 9, 1952, only one successor seemed a natural fit.

As such, the Embassy of Israel sent a letter to Einstein on November 17, officially offering him the presidency.

He would have to move to Israel, the letter said, but he wouldn’t have to worry about the job being a distraction from his other interests. It was just the presidency, after all.

“The Prime Minister assures me that in such circumstances complete facility and freedom to pursue your great scientific work would be afforded by a government and people who are fully conscious of the supreme significance of your labors,” Abba Ebban, an Israeli diplomat, wrote.

And despite Einstein’s old age — he was 73 at the time — he would have been a popular choice. For one, thing, as a German-born professor who found refuge in America during Hitler’s rise to power, he had been a long-time advocate for the establishment of a persecution-free sanctuary for the Jews.

“Zionism springs from an even deeper motive than Jewish suffering,” he is quoted as saying in a 1929 issue of the Manchester Guardian. “It is rooted in a Jewish spiritual tradition whose maintenance and development are for Jews the basis of their continued existence as a community.”

Furthermore, Einstein’s leadership in establishing the Hebrew University of Jerusalem suggested that he might be a willing candidate, and proponents thought his mathematics expertise would have been useful to the burgeoning state.

“He might even be able to work out the mathematics of our economy and make sense out of it,” one statistician said to TIME magazine.

However, Einstein turned the offer down, insisting that he — the man whose last name is synonymous with “genius” — was not qualified. He also cited old age, inexperience, and insufficient people skills as reasons why he wouldn’t be a good choice. (Imagine, someone turning down a presidency based on a lack of experience, old age, and an inability to deal properly with people.)

“All my life I have dealt with objective matters, hence I lack both the natural aptitude and the experience to deal properly with people and to exercise official functions,” he wrote.

Though he was resolute in his decision, Einstein hoped it wouldn’t reflect badly on his relationship with the Jewish community – a connection he called his “strongest human bond.”

For more fun Einstein information, take a look atwhat Albert Einstein’s desk looked like on the day he died, or read 25 things you didn’t know about Einstein.