These famous inventors don't actually deserve credit for the inventions that made them famous. Here's who we should be remembering instead.

Image Sources (clockwise from top left): Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons, Michael Jackson Wiki.

While the light bulb may be the quintessential human invention — not to mention the very symbol of inspiration itself — the process of invention couldn’t be further from flipping a light switch. Invention is a slow, gradual grind, with one inventor carefully building off the achievements of the last until we finally have the product that history has decided is the invention.

However, once we have these inventions and the famous inventors supposedly responsible for them, we tend to forget those inventors that came before, and instead pretend that that last inventor in the chain conjured brilliance from nothing, turning darkness into light.

Worse yet, we sometimes ignore the inventor who should have been known as the last one in the chain. Often, those not-so-famous inventors are ignored because they aren’t from the right class, or don’t have enough clout, or aren’t from the right nation.

Whatever the reason, here are six famous inventors — including the man behind the light bulb itself — who don’t actually deserve credit for their most famous creation.

Famous Inventors: Alexander Graham Bell Didn’t Invent The Telephone

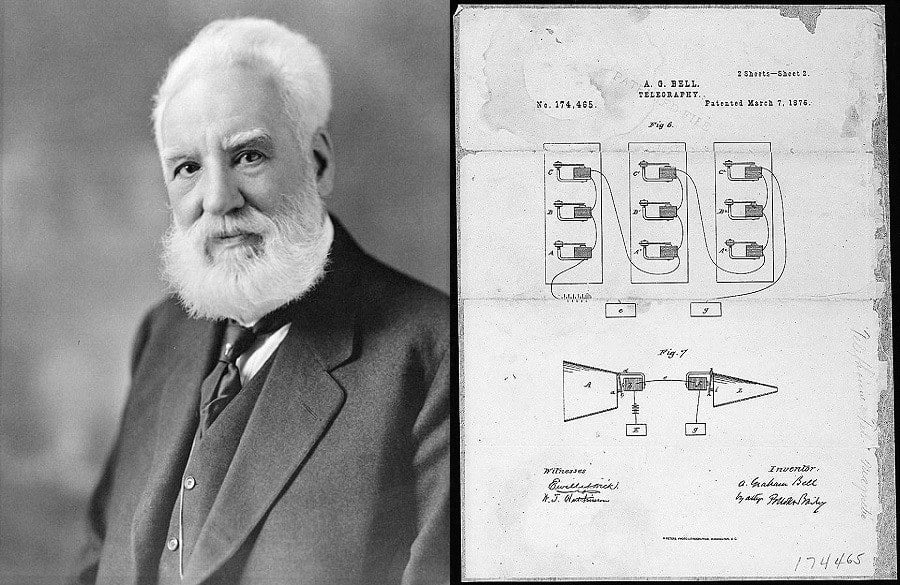

Left: Alexander Graham Bell, one of history’s most famous inventors. Right: Bell’s original patent drawing for the telephone. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons.

On June 2, 1875, Alexander Graham Bell and his assistant, Thomas Watson, were working on their harmonic telegraph, a device that would transmit sound at a distance via the vibrations of steel reeds charged with currents. When one of the reeds failed to respond to a current, Bell, thinking the reed had stuck to the nearby magnet used to generate that current, asked Watson to pluck the reed with his hand. When he did, Bell actually heard the sound on his receiver far away. They’d successfully transmitted sound at a distance.

One month later, they transmitted the human voice (Bell saying “Mr. Watson — come here — I want to see you.”). After a few more months of tinkering and refining, on March 7, 1876, Bell was awarded U.S. Patent 174,465, and the origin story of the telephone, as we know it, came to an end.

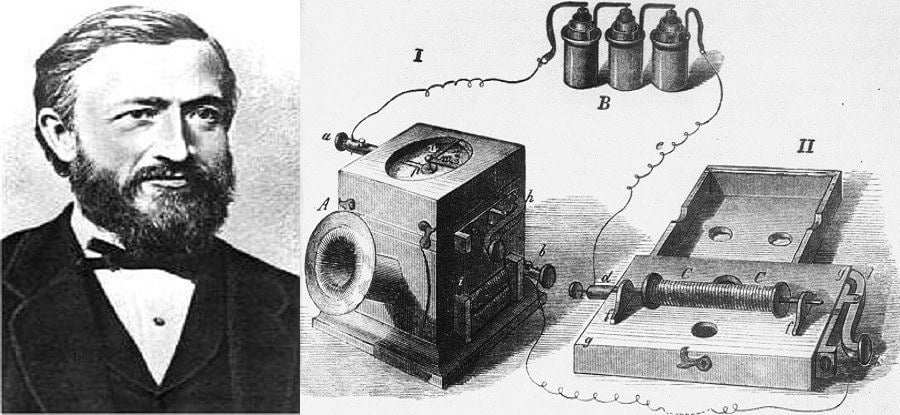

Elisha Gray. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

However, the true drama of this origin story happened nearly a month before that patent (tellingly titled “Improvements In Telegraphy”) was awarded. It was Valentine’s Day, 1876, and not one, but two, men were racing to the Patent Office. The one who got there first, however, wasn’t Alexander Graham Bell, but Elisha Gray.

Gray, a man whose name rarely ranks among the list of history’s most famous inventors, had been working on a sound transmitting device for years, similar to Bell’s except for its use of a liquid transmitter. And on the morning of February 14, Gray’s lawyer got to the Patent Office bright and early and handed in his paperwork — where it sat, at the bottom of the pile, until the afternoon. In the meantime, just before noon, Bell’s lawyer reached the Patent Office, and whether by force or clout, had Bell’s paperwork pushed through the pile and filed immediately.

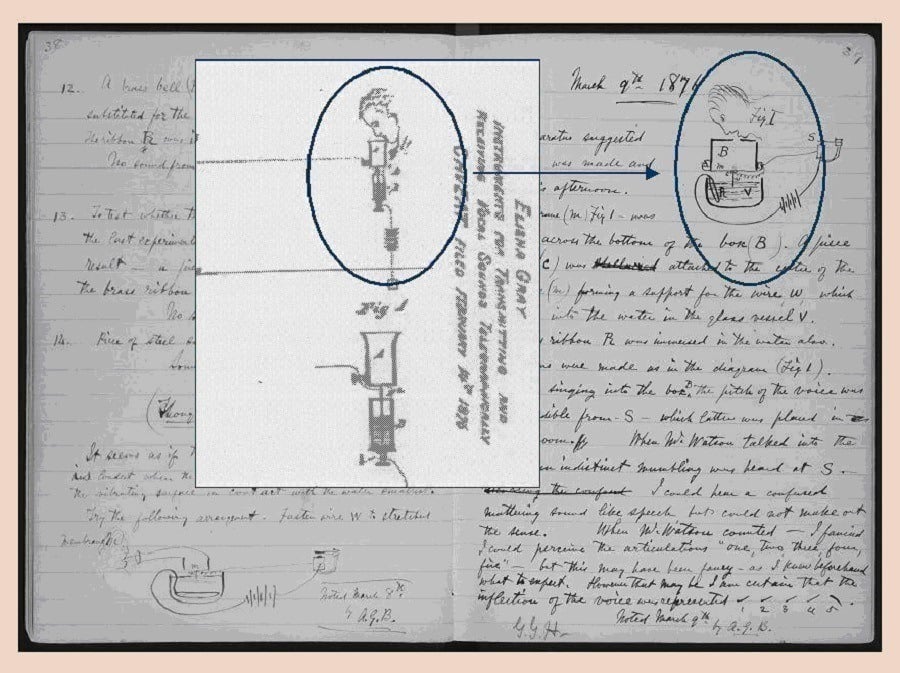

Excerpts from Gray’s patent caveat of February 14 (inset) compared with Bell’s notebook of March 8, highlighting the section Bell reportedly stole from Gray. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

And it’s not just that Gray got there first, it’s that many scholars claim that the paperwork Bell did file that day included a section (regarding that liquid transmitter and the use of variable electric current) that had been stolen from Gray’s work. The patent examiner who looked at both Bell and Gray’s paperwork, saw this red flag and suspended Bell’s application for 90 days while he reviewed the claims.

However, Bell and his lawyer were able to persuade the examiner to lift the suspension after they produced an earlier patent filing of Bell’s that showed the use of a liquid transmitter. That filing showed that both the liquid being used and the way it was being used were not applicable to the telephone. Nevertheless, the examiner was able to be convinced and the patent was Bell’s.

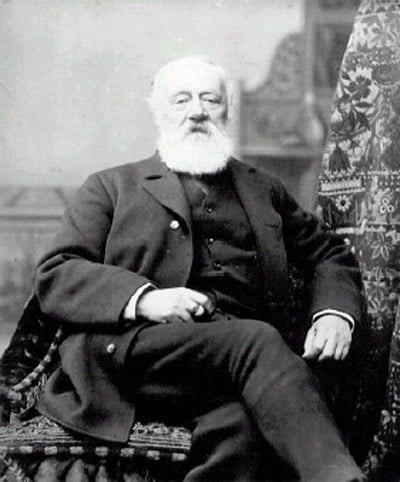

Antonio Meucci. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

And while Bell vs. Gray is certainly the most dramatic showdown in this whole tale, it also obscures the pioneering work of nearly a dozen men who could also lay claim to the telephone’s invention. Chief among them is Antonio Meucci (not among history’s most famous inventors, but among its most important), who had achieved success with primitive telephones all the way back in the 1830s, and was able to transmit his voice electromagnetically, as Bell eventually would, by the mid-1850s.

Meucci even filed a caveat (a formal intention to file a patent, as opposed to a complete filing) with the Patent Office in 1871 that essentially describes the device Bell would patent five years later. However, Meucci, who live in poverty most of his life, wasn’t able to afford the $10 caveat renewal fee in 1874. A 2002 U.S. House of Representatives resolution states, “If Meucci had been able to pay the $10 fee to maintain the caveat after 1874, no patent could have been issued to Bell.”

Left: Johann Philipp Reis. Right: Reis’ drawing of his telephone invention. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons.

Even Meucci’s claim obscures the work of Johann Philipp Reis, who constructed an electromagnetic device that transmitted human speech back in 1860. However, the sound quality was relatively poor and the device wasn’t commercially practical. Nevertheless, the first words transmitted electromagnetically by a device we could call a telephone weren’t Bell’s immortal “Mr. Watson — come here — I want to see you.,” but instead Reis’ test phrase, chosen for its sonic characteristics in the original German: “The horse doesn’t eat cucumber salad.”