If the Flour Riot of 1837 teaches us anything, it's that people often believe what they read — and will act upon it.

Life of Pix/Pexels

Throughout history, food shortages or the uneven distribution of food have sparked panic all over the world, from the Moscow uprising of 1648, when the Russian government replaced various taxes with a universal tax on salt, to recent food shortages in Venezuela.

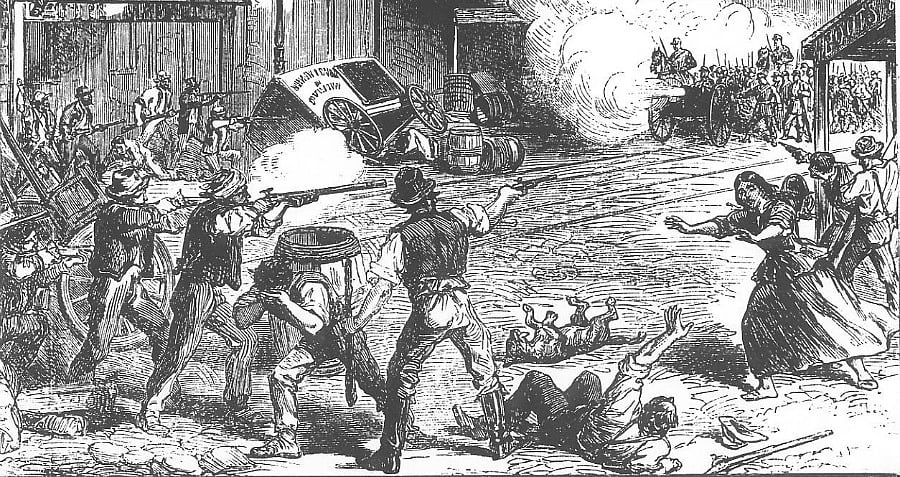

One such shortage occurred in the early 19th century and resulted in a rash of sudden violence in Manhattan. Known as the Flour Riot of 1837, the uprising occurred after poorer residents of the city became fearful that their wealthier neighbors were stockpiling large amounts of flour and grain in nearby warehouses.

Rioting in mid-19th century Manhattan was, of course, not entirely unheard of, and when compared to the Astor Place riots of 1849, and the Draft Riots of 1863, the latter of which took place over the course of a week, the Flour Riot was by far less violent and damaging.

Resulting in zero deaths and very little physical damage, aside from the 500 barrels of flour and 1,000 bushels of wheat destroyed, the Flour Riot didn’t go down in history as a particularly brutal one, though it does remain exceptional for a number of reasons.

While not as well-known as later riots in the city, the Flour Riot was exceptional in that it was inflamed entirely by a rumor. The city’s citizens did notice an increase in the cost of flour — which had jumped from $7 to $12 per barrel between the years 1836 and 1837 — and many feared that prices would continue to increase and further immiserate an already oppressed and impoverished lower class.

The recent invention of the penny press — inexpensive, tabloid-style newspapers — further stoked the anger of the masses. It wasn’t long before rumors began to spread, with some even stating that the cost of flour could rise to $20 per barrel, causing public outrage.

Wikimedia Commons

Costing only one penny, unlike the six their competitors were charging, penny press papers, such as The New York Herald, appealed to the New York City working class. Using interviews and on-site reporting, these papers reflected the experiences of their readers and in the case of the Flour Riot, successfully agitated an already frustrated group of people.

Wikimedia Commons

Printed notices began appearing on street corners, one of which was a call to action encouraging its readers to gather at City Hall on Monday, February 13 to attend a meeting called to discuss the issue.

A crowd of around 5,000 New Yorkers braved the winter weather to show up that day. Several speakers, many former candidates for city office positions, spoke about the economic conditions of the country.

The final speaker, still unidentified to this day, took to the podium to call out two specific merchant firms — Eli Hart & Co., and S.H. Herrick & Co. — and accused them both of hoarding flour. Hart was said to be stockpiling 53,000 barrels of the stuff in his warehouse, and an eyewitness account recalls the rousing speech.

“Fellow-citizens! Mr. Hart has now 53,000 barrels of flour in his store; let us go and offer him eight dollars a barrel, and if he does not take it” — here some person touched the orator on the shoulder, and he suddenly lowered his voice, and finished his sentence by saying, “we shall depart from him in peace,” said the orator according to the eyewitness in an interview originally published in The Commercial Register on February 14, 1837.

The mob then marched to Hart’s warehouse, located on the corner of Washington and Cortlandt streets, where they began tossing hundreds of barrels of flour into the streets of Lower Manhattan. Two additional warehouses were also trashed that night, although no significant destruction was brought onto either.

The Flour Riot, although not exactly significant, did lead to the hiring of more city watchmen, and indicated the need for a professional police force, which would eventually become established in 1845.

The riot also tipped off what would be known as the Panic of 1837, a financial crisis which resulted in a seven-year recession.

There’s more picketing where that came from. Check out this list of America’s worst riots as well as this look at the five strangest riots in history.