After Henrietta Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951, doctors at Johns Hopkins cultured her cells for use in medical research — without her permission.

APWhen Henrietta Lacks went to Johns Hopkins for cancer treatment, she unwittingly made a tremendous contribution to science.

Johns Hopkins Hospital has long been considered one of the best hospitals in America. Back in the 1950s, it was also one of the few places where Black patients could seek quality medical care.

In February 1951, an African American woman named Henrietta Lacks arrived at Johns Hopkins Hospital to seek treatment for heavy vaginal bleeding that had nothing to do with menstruation. She was diagnosed with cervical cancer and died later that same year.

However, doctors who treated Lacks discovered that her cells possessed the unique ability to replicate and survive outside of the body. Her cells, dubbed “HeLa cells,” were promptly distributed to the larger medical field for research — without the late Lacks’ consent.

Calls to recognize the unethical distribution of Henrietta Lacks’ cells have grown since her story became widely known in the late 2010s, including demands for monetary support from those who profited off her body.

Henrietta Lacks’ Fateful Diagnosis

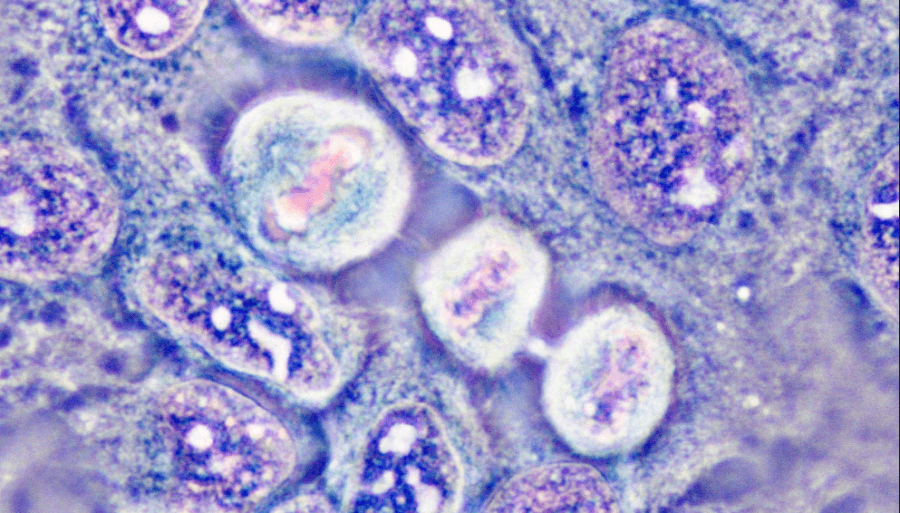

Wikimedia CommonsThe HeLa cells up close.

Henrietta Lacks was a 30-year-old Black woman who was originally from Virginia. A descendant of freed slaves, she and her husband once worked as farmers on tobacco fields.

By the time Lacks was 21, the couple had moved their family to Baltimore in the hopes of better employment opportunities. They had five children, and it was shortly after the birth of their last son, Joe, that Henrietta — or “Hennie” as her family called her — noticed her abnormal bleeding.

Dr. Howard Jones, the gynecologist who examined Lacks, found a large tumor on her cervix. Less than a week later, she found out that it was cancerous.

According to the 2010 book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot, Henrietta Lacks was afraid of being mistreated by white doctors during the Jim Crow era. But the painful “knot on her womb” forced her to seek out medical help. She initially hid her diagnosis from her family, but was unable to keep it a secret as her pain continued to grow.

Cancer treatment in the 1950s had yet to advance to where it is today. As medical records show, Lacks underwent radium treatments for her cervical cancer. While it was the best treatment the hospital could offer her at the time, her cells continued to reproduce at an unusually high rate.

As Lacks’ condition worsened, Dr. George Gey, a prominent cancer and virus researcher, found something else unusual about Henrietta Lacks’ cells.

More often than not, cells in samples that Gey had collected from other patients died off so quickly that he was unable to study them. But Lacks’ cells not only survived but continued to multiply, doubling every 20 to 24 hours. This meant that doctors were able to keep the cells alive outside of her body to help further their research on cancer cells.

Unfortunately, this abnormality also meant that the cancer cells inside Lacks’ body were multiplying at a rate faster than the radium could kill them. Less than eight months after she had first walked into the hospital, Henrietta Lacks died.

The Unwitting Mother Of Modern Medicine

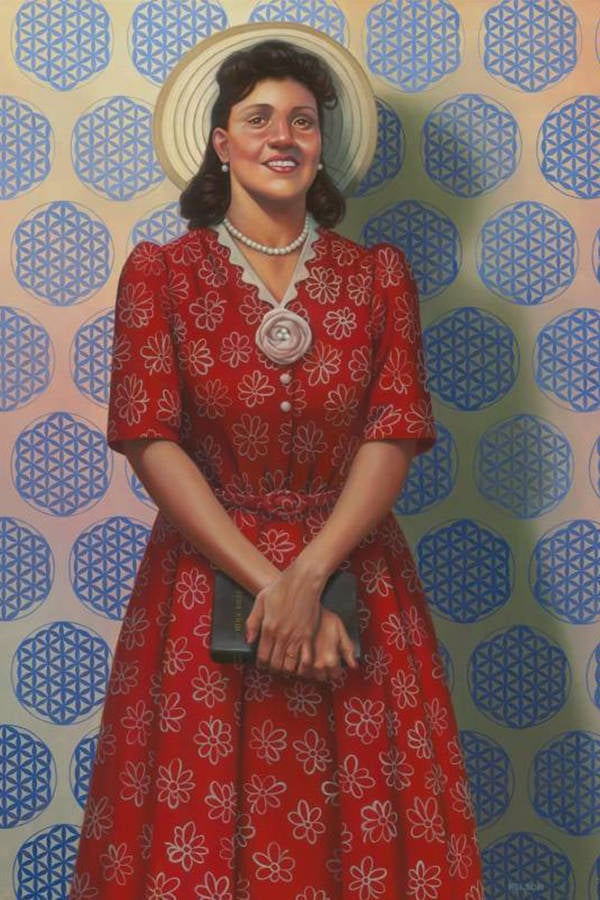

National Portrait Gallery In 2017, a portrait of Henrietta Lacks was installed at the National Portrait Gallery.

As the family Henrietta Lacks left behind mourned her, their loved one’s cells had taken a new life of their own among medical experts.

Scientists dubbed the unusual cells “HeLa cells,” which was a combination of the first two letters from Lacks’ first and last names. They were using them not only to study the growth of cancer cells and how to potentially destroy them but also to learn more about the human genome.

Dr. Gey sent samples of the constantly-multiplying HeLa cells to researchers across the U.S. Before long, his late patient’s cells were distributed all over the country — and in other countries as well.

The cells not only helped with cancer research, but also with the development of vaccines for polio and HPV, as well as IVF and other groundbreaking advancements in medicine.

But Lacks’ family remained unaware of her unique contribution to science. It wasn’t until they received a call from researchers in the 1970s — years after her cells were already dispersed — asking them about participating in additional studies that they finally learned the truth.

The dubious way in which the HeLa cells had been obtained and distributed raised issues of bioethics among some experts. The Lacks family became concerned that the sample had been taken without Lacks’ permission.

They also expressed frustration that private entities in the biomedical field were making billions off of the use of their late family member while many of their own living relatives couldn’t even afford health insurance.

Much like cancer treatment, the concept of informed consent within the medical field was still deeply flawed during the 1950s. At the time Lacks came to Johns Hopkins, cervical cancer was killing 15,000 women per year.

Dr. Daniel Ford, director at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, remarked that the incident had occurred in an era when “researchers got a little carried away with science and sometimes forgot the patient.” Still, it was no excuse to violate a patient’s privacy, let alone in the extreme manner that it had been done in Henrietta Lacks’ case.

Years after the release of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, HBO produced a 2017 film adaptation for television based on the book. The film, starring Oprah Winfrey as Lacks’ daughter who uncovered the truth about her mother’s cells being used for science, earned a Primetime Emmy Award nomination for Outstanding Television Movie.

Belated Recognition For Henrietta Lacks From The Medical Community

By 2017, the HeLa cells that were harvested from the late Henrietta Lacks had been studied in 142 countries, leading to countless breakthroughs in medical science, including research that earned two Nobel Prizes.

The cells have also contributed to more than 17,000 patents and 110,000 scientific papers, establishing Lacks as the “mother of modern medicine” — albeit unwittingly. Her cells continue to be used in significant studies related to cancer, AIDS, and several other medical issues.

Ever since the case of Henrietta Lacks became widely known, growing pressure from the public has forced a reckoning within the multibillion-dollar medical industry, especially among private companies and research labs that have benefited from the use of HeLa cells.

Calls from researchers and health advocates to recognize the unethical way in which Henrietta Lacks’ cells were distributed have prompted efforts from Johns Hopkins to rectify its troubling conduct against its patient. Over the past decade, the institute has worked with Lacks’ family to honor her legacy through scholarships, symposiums, and awards in tribute to her.

In August 2020, Abcam and the Samara Reck-Peterson lab — two entities that have benefited from the use of HeLa cells — went a step further. They announced monetary donations that would directly benefit the Henrietta Lacks Foundation and support the education of her future descendants.

It’s a powerful gesture that will hopefully be emulated by others who have benefited from the HeLa cells. Aside from the astounding medical breakthroughs achieved through the use of these cells, the biggest contribution made by Henrietta Lacks to the sciences is perhaps the conversation that her case has helped sparked in regard to bioethics, privacy, and consent issues within the field of medical science.

It has also brought forth important examinations about the health disparities that continue to impact minority patients like Henrietta Lacks. Even today, some of them continue to be treated with disregard by people in the medical field, in some cases with violence.

Nevertheless, the HeLa cells will no doubt continue to save countless more lives in the future.

After learning about Henrietta Lacks and her world-changing HeLa cells, read about Walter Freeman and the history of the lobotomy. Then, check out the scientists who grew a beating human heart from stem cells.