They were called the Special Operations Executive, but also known as the "Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare" — a nickname they more than earned.

Wikimedia CommonsWinston Churchill

When Britain stood alone against the Nazis at the outset of World War II, Prime Minister Winston Churchill realized that his island nation would have to use every resource and tactic available to defeat the storm of evil that had enveloped much of the European continent. So, He established a secret war ministry called the Special Operations Executive (perhaps better known as the “Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare”).

The SOE operated outside the conventional rules of warfare, hence the playful reference to its activities as “ungentlemanly.” It supported resistance movements in occupied countries, carried out a range of covert operations, and developed innovative guerrilla warfare techniques and equipment.

The SOE employed a variety of people — from military and civilian backgrounds — for its secretive missions, including scientists, engineers, and inventors who worked to develop various new tools and weapons of sabotage

While some of the ministry’s tactics might seem more suited to a James Bond script than to real life, the ultimate success of these operations is a true testament to the power of human ingenuity.

The Formation Of The ‘Ministry Of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Dismayed by the rapid fall of France in 1940 and eager to take the fight directly to the enemy, Prime Minister Winston Churchill envisioned a secret organization that would carry out acts of sabotage, subversion, and support for resistance movements in Nazi-occupied Europe.

He tasked Hugh Dalton, the Minister of Economic Warfare, with forming this clandestine force. Dalton, inspired by the tactics of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), drew up plans for a centralized sabotage organization.

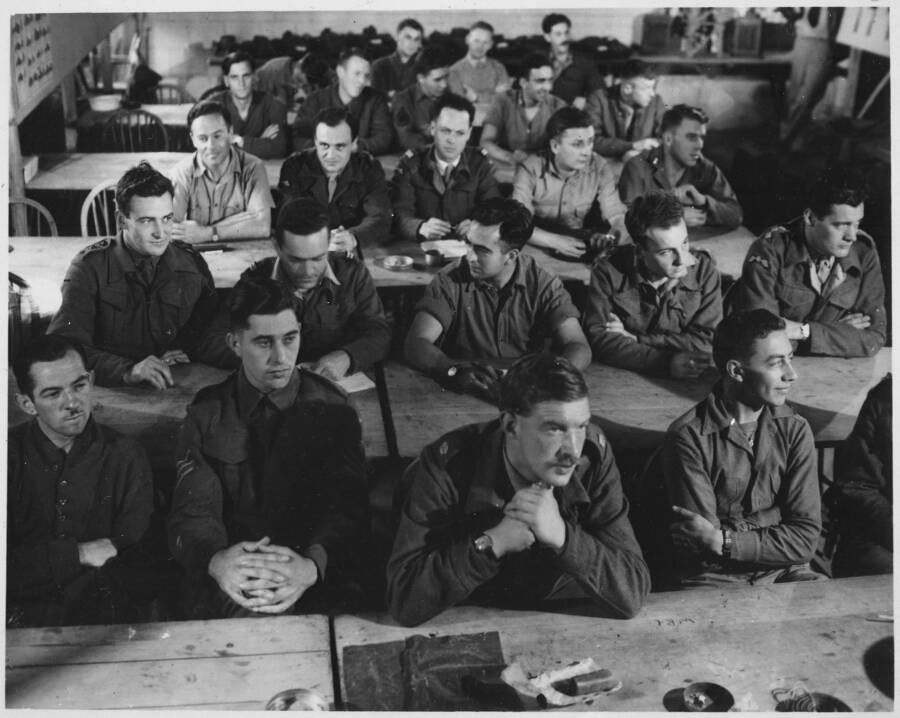

Wikimedia CommonsBritish operatives in a demolitions class at Milton Hall.

On July 22, 1940, Churchill formally approved the SOE, instructing its agents to “set Europe ablaze.” The organization merged three existing secret departments, creating a force dedicated to unconventional warfare behind enemy lines.

Not long after its formation, the SOE conducted numerous small operations, making it difficult to pinpoint the organization’s very first mission. That said, there was one standout mission early on that truly set the standard for how the SOE would conduct its future missions: Operation Postmaster.

Operation Postmaster: A Daring Raid In Neutral Waters

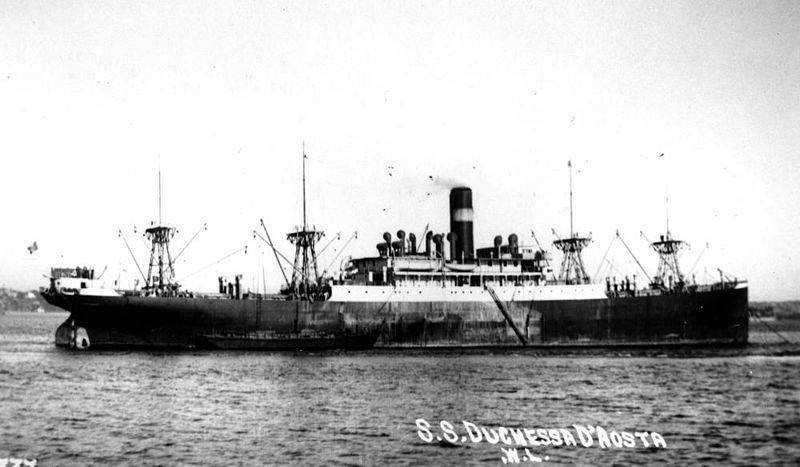

Wikimedia CommonsThe Duchessa D’Aosta

The Special Operations Executive got their first chance to prove themselves in January of 1942. Word had gotten back to the British that the Duchessa d’Aosta, an Italian ocean liner that had claimed shelter in the port of Fernando Po, was actually a listening vessel supplying the Germans with Allied shipping movements. The Duchessa was soon joined by the German ships Likomba and Burnundi, convincing the British that the time had come to act.

There was one problem: Fernando Po was controlled by Spain, an officially neutral country. A blatant attack on the ships in a neutral port could push Spain to fight for the Axis. With the most powerful navy in the world unable to act for political reasons, it was time to call in the “ungentlemen.”

Officer Colin Gubbins came up with an ingenious plan known as Operation Postmaster: With a handful of agents, some help from the locals, and a few well-placed minor explosives, he would cause the three ships to simply vanish from the harbor. The threat of the spying ships would be removed and the Allies could claim ignorance.

Although Spain was officially neutral, the governor of Fernando Po, Captain Victor Sanchez-Diez, was decidedly pro-Nazi. With some help from agents in place on the island (including the local British chaplain), Gubbins not only managed to acquire some compromising photos of Sanchez-Diez with his mistress (which they used as leverage to convince him to loosen up the security on the island), but even managed to slip an agent onto the Italian ship, where he discovered that the sailors were astonishingly lax in their guard duties.

One night, under the cover of darkness, a small group of Special Operations Executive agents slipped into the harbor in two tugboats. The captains of all three ships had been invited to a fabulous party that evening arranged by a local named Abelino Zorilla.

Zorilla was an excellent host and master of detail, he kept the alcohol flowing and arranged the seating plan so his honored guests had a full view of the party with their backs to the window. He was, conveniently, also a devoted anti-fascist recruited by the British to assist with the mission.

As the party was underway, the commandos boarded the Axis vessels, overpowered the skeleton crews that had been left behind on guard duty and severed the chains docking the ships with explosives. In no time at all, the three vessels were being tugged out to sea before vanishing into the night.

Of course, not even the drunkest German officers could fail to hear the tremendous explosions from the harbor. Initially thinking it was an air raid, they launched anti-aircraft fire, and set the entire island into a general panic.

When they finally realized there was no attack from the skies, the drunken crews made their way down to the docks, to find their ships gone without a trace. The shock of the inebriated sailors made for such a spectacle that the locals who had gathered around erupted into full-blown laughter.

The captain of the Likomba, however, did not find the situation quite so funny. He stormed into the British Consulate demanding to know what they had done with his ship. In his frustration, the captain actually lashed out at the consul, prompting the vice-consul to hit him with a left hook so vicious that the German “collapsed in a heap, split his pants and emptied his bowels on the floor.”

The SOE agents had suffered no casualties, successfully eliminated the threat of the three vessels, and, most importantly, avoided an outright violation of Spain’s neutrality. And the Allies were able to completely deny responsibility; not-quite-untruthfully declaring that no British ship had been in the vicinity of Fernando Po that particular evening.

The SOE’s reputation for carrying out delicate and dangerous missions was successfully established.

The Aftermath And Leadership Changes

While Operation Postmaster had been a major success, not every mission the SOE underwent saw the same favorable result. Throughout the summer and into the early autumn after the operation, SOE agents faced several early setbacks, including several agents being arrested by the Gestapo.

Other local resistance networks working with the SOE also proved to have been compromised. On top of this, several early missions failed simply due to logistical failures, breakdowns in communication, or straight up betrayal — all of which hampered morale.

Of course, the SOE was still in its infancy during this period and still had yet to establish secure drop zones, forge reliable documents, and develop proper vetting procedures for potential contacts across Europe.

Then, in October 1941, Sir Frank Nelson was appointed as the head of the SOE. In his new role, Nelson focused specifically on improving coordination with the Allied war effort, translating into more mission requests designed to disrupt specific German operations or prepare the way for conventional military forces.

This renewed momentum and focus ultimately led to anothe major operation for the SOE — one that showed just how cunning and deceptive this specialized group could be.

The St. Nazaire Raid

Wikimedia CommonsThe HMS Campbeltown being loaded with explosives.

In 1942, the Tirpitz was the most powerful warship in the world. Unfortunately for the British, she was also the latest addition to Hitler’s navy.

Churchill knew that, if unleashed in the Atlantic, the vessel would be able to inflict incalculable damage on the convoys that were so vital to Britain’s survival. The prime minister was convinced that “the whole strategy of the war turns at this period on this ship.”

The Tirpitz was too big and too well-defended to be sabotaged outright, so the wily minds at the Special Operations Executive came up with an entirely new strategy: If they couldn’t hit the ship directly, they would instead sabotage the dock she relied on for repairs and leave her without a safe haven.

The Special Operations Executive was able to determine that the only dock capable of repairing a ship the size of the Tirpitz was the Normandie dock at St. Nazaire in Nazi-occupied France. If the dock were to be destroyed, the Tirpitz would be forced to return to Germany for any repairs via the English channel.

Since St. Nazaire was of such strategic importance, it was heavily defended. The dock itself was enormous and would require a tremendous amount of explosives being brought in at close range.

In a tremendously daring plan, it was decided that agents would pack an old destroyer to the brim with delayed-action explosives and have a team of commandos navigate it up the channel before ramming directly into the dock’s gates.

The men selected for the mission knew that they had a very slim chance of getting out alive and that the entire plan hinged on the effectiveness of the delayed-action fuses (which had been specially developed by the Special Operations Executive’s explosives expert). If the fuses went off too soon, the HMS Campbeltown would be blown to pieces with the entire crew still on board. Despite the enormous risk, the mission went forward.

Disguised as a damaged German destroyer requesting permission to dock, the Campbeltown and her crew initially managed to surprise the Germans and delay any response. After the ruse was inevitably discovered, the ship took heavy fire from all sides before she, at last, hit her target and rammed into the gates of the dock.

Chaos reigned until the early hours of the morning, with nearly 75 percent of the Special Operations Executive commandos injured or killed. The Campbeltown was slated to explode at 7 a.m. and, as the surviving agents began to be captured and rounded up, they all began counting down the minutes.

When it reached 11 a.m., on the morning of March 28, the commandos gave up hope and accepted their mission as a failure. To add insult to injury, one German officer began to taunt them, telling his captives that “your people obviously did not know what a hefty thing that lock-gate is.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe destroyed St. Nazaire docks.

Then, in a moment that could not have been more perfectly timed in any Bond film, the Campbeltown exploded with such force that the locals thought an earthquake had struck St. Nazaire. With remarkable sangfroid, one of the British officers simply replied “that, I hope, is proof that we did not underestimate the strength of the gate.”

Although victory had come at the cost of more than 150 casualties, the Normandie dock was out of commission for the next decade and the dreaded Tirpitz did not venture into the Atlantic for the rest of the war.

Aftermath Of The St. Nazaire Raid

While the SOE suffered major losses of their own during the raid, it was by all means a major strategic victory — and considered by many to be one of the most daring and successful commando operations of World War II.

Unfortunately, it also deeply angered Hitler, who then issued the infamous “Commando Order,” calling for the execution of captured operatives.

Still, the operation’s success proved the true capabilities of the SOE, and throughout the year they would continue their operations with a sense of renewed purpose.

And less than two months after the raid, they would embark on another dangerous mission — one that sought to eliminate one of Germany’s top Nazis.

Operation Anthropoid

If there was one man who embodied everything that the Special Operations Executive was fighting against, it was Reinhard Heydrich.

Wikimedia CommonsReinard Heydrich, the target of Operation Anthropoid.

Dubbed by Hitler himself as “the man with the iron heart,” Heydrich was head of the dreaded Gestapo and the mastermind behind both the Kristallnacht pogrom and the infamous Wannsee Conference held to organize the “final solution” to the Jewish question. The solution determined at that conference would soon claim the lives of millions of men, women, and children across Europe.

In 1941, Heydrich was appointed Reichsprotektor of what is now the Czech Republic, where he was so ruthless in his arrests and executions that he earned himself the nickname “the butcher of Prague.” Despite Heydrich’s efforts to crush the will of the entire country, the Czechs ran an effective resistance network, aided and abetted by their government-in-exile in Britain.

Together with the SOE, the exiled Czechs came up with a plan to take out the Nazi terrorizing their homeland. Although they knew the German reprisals would be swift and merciless, Heydrich was already murdering so many civilians that they determined the benefits of assassinating such a high-ranking officer would far outweigh the risks.

Czech soldiers had been training alongside SOE commandos at a top-secret camp in Britain where they became skilled in the arts of sabotage and killing. The Head of Czech Intelligence hand-picked two of the most skilled officers to carry out the assassination: Jan Kubiš and Jozef Gabčík.

Armed with grenades, machine guns, and pistols, the team would be dropped behind enemy lines and hide out until they could carry out the attack. Thanks to intelligence from anti-Nazi locals, the SOE knew that Heydrich traveled in an open-top, armor-plated Mercedes.

The plan was to plant Kubiš and Gabčík at a bend in the road on the car’s daily route from Prague, where it would be forced to slow down and they would be able to hit the vehicle with machine-gun fire and explosives.

On the day of the assassination, May 27, 1942, Heydrich chose to spend some extra time with his family, throwing off his usual routine. After a tense half-hour of waiting, the two commandos, at last, saw the Mercedes slowing down around the bend. Gabčík stepped in front of the car intending to shoot both Heydrich and his driver, but his machine gun jammed, leaving him exposed in the open road.

Wikimedia CommonsReinhard Heydrich’s car after the attack.

When Heydrich and his bodyguard stepped from the vehicle intending to kill the would-be assassin, Kubiš lobbed his grenade and managed to hit the rear of the Mercedes.

Although Heydrich was not hit directly, the explosive did its job: He was badly injured by shrapnel, and the force of the blast drove pieces of the car and dirt into his wounds, which became infected and killed him eight days later.

Kubiš and Gabčík managed to escape the scene, but, as they anticipated, the Nazi reprisals were swift and fearsome. The two were eventually tracked down and killed, along with dozens of other Czech civilians accused of aiding them. Nevertheless, for all of the horror of its aftermath, Operation Anthropoid was considered the Special Operations Executive’s highest-profile success.

Then, in early 1943, the SOE would prove that sabotage was not its only strongsuit.

Operation Mincemeat

In February 1943, Major-General Sir Colin Gubbins, a veteran of irregular warfare, assumed leadership of the SOE. Gubbins’ approach was more aggressive, leading to intensified operations that took even greater risks.

Gubbins was a strong proponent of “doing and not just planning” and sought to dismantle and disrupt the German war effort no matter the cost. As a result, agent fatalities increased — but so did the organization’s effectiveness.

Gubbins particularly fostered closer integration between SOE operations and the overall Allied war plan, which would eventually translate into vital D-Day missions focused on crippling German communications and transport networks.

Public DomainColin Gubbins (center) the Chief of the SOE.

Which brings us to April 1943, when the SOE, under Gubbins’ command, conducted Operation Mincemeat. Unlike previous operations, Mincemeat’s goal was not to necessarily destroy German assets — rather, its goal was to confuse the German’s and supply them with false information.

The operation began when the British obtained the coprse of a homeless Welshman by the name of Glyndwr Michael, who had died from ingesting rat poison. SOE operatives disguised Michael as a fake Royal Marines officer named William Martin, planting meticulously crafted false documents on the body that detailed Allied plans to invade Greece and Sardinia, with Sicily acting as a diversionary target.

Among these false documents were personal letters and official-looking plans detailing troop movements and landing zones.

Public DomainCharles Cholmondeley and Ewen Montagu on April 17, 1943, transporting Michael’s body.

Michael’s body was then released off the coast of Spain — a country known for its neutrality but with German intelligence connections.

As expected, Michael’s body, and the false documents, came into the possession of German intelligence. Thankfully, they took the bait, and as a result diverted troops and resources away from Sicily and towards Greece and Sardinia.

Then, in July 1943, the Allies invaded Sicily and faced significantly less resistance than they would have, had the SOE not intervened. Operation Mincemeat was a landmark moment for the organization, but it also further illustrated the benefits of deception in times of war.

Curiously enough, the initial idea for this deceptive tactic came from James Bond creator Ian Fleming, who was at the time the assistant to Admiral Godfrey, the head of naval intelligence.

Then, in October of that same year, the SOE once again proved that it was no one trick pony, illustrating its adaptability in obtaining vital supplies during Operation Bridford.

Operation Bridford

Wikimedia CommonsGun boats in action.

Ball bearings. Not exactly the stuff that makes for the plot of a glamorous wartime spy mission. Yet technical and dry though the term might sound, ball bearings were crucial to the war effort, as they were necessary to run any kind of engine.

By 1941, the British were running dangerously low on this important technology because the Germans had successfully destroyed all of their factories producing the bearings. The British had equal success in destroying the Germans’ factories, meaning that there was only one country in Europe left successfully producing ball bearings: Sweden.

Like Spain, Sweden was officially a neutral country. Also like Spain, Sweden was much less hesitant in providing assistance to the Germans than to the British, particularly when it came to supplying the warring powers with ball bearings.

Once again, the British needed to somehow meet their objective without violating another country’s neutrality: another mission for the Special Operations Executive.

A group of modern-day swashbucklers and Vikings led by a dashing Arctic explorer on a mission to cross enemy lines in the freezing Baltic: Now that is the stuff of a glamorous spy story.

Sir George Binney was working as the representative of the U.K. Ministry of Supply in Sweden when the war broke out. His job had been to obtain steel, tools, and other supplies (ball bearings among them) to send back to Britain.

Once the war began, he needed to come up with slightly more ingenious methods for accomplishing his task. A former Arctic explorer, Binney was no stranger to organizing dangerous missions in freezing conditions and, together with the Special Operations Executive, he managed to work out a brilliant plan named Operation Bridford.

Back in the late 1930s, Turkey had commissioned eight motor gunboats from Britain; these vessels were larger than the average motorboat, but still capable of moving quickly through the water. After the war started, the Royal Navy requisitioned these vessels and outfitted them with even more guns. The Special Operations Executive determined they would be perfect for a series of blockade running operations.

The missions were planned for September of 1943, when the agents would be able to take advantage of the maximum hours of darkness. The motorboats would need to make the two-day journey to Sweden, pick up supplies without detection, then make the two-day return journey, all the while avoiding the German Baltic Navy.

Wikimedia CommonsNorwegian exiles during the war.

For diplomatic purposes, the boats could not be manned by the Royal Navy; if caught by the Germans, they would be considered to have violated Sweden’s neutrality. Luckily, there was no shortage of local sailors and fishermen willing to volunteer, despite the danger of the mission.

Many Norwegian sailors who had been stranded on their ships when their country was invaded by the Nazis were also eager to fight back in any way they could. These groups of volunteers in their motorboats managed to make nearly ten raids across enemy lines and bring back a total of 350 tons of supplies, allowing the Royal Navy to avoid taking direct action and violating Sweden’s neutrality.

The Englandspiel Disaster — The SOE’s Worst Blunder

As 1943 turned into 1944, the war began to see a favorable shift for the Allies. However, not all was well.

Unbeknownst to the SOE, in early 1942, the Germans had captured a Dutch SOE agent carrying a radio transmitter and codes. Rather than killing the agent, however, the Germans decided to use this to their advantage.

Holding the agent captive, they forced him to keep communicating with the SOE, ultimately tricking them into sending agents directly into the hands of the Germans. They also supplied the SOE with false intelligence, essentially taking control of the SOE’s Dutch operations.

This counterintelligence operation went on for nearly two years, during which time the SOE parachuted more than 50 agents straight into capture, most of whom were either executed or sent to concentration camps. The Germans also seized hundreds of weapons and supplies intended for the Dutch resistance.

It would have likely continued, too, had two Dutch SOE agents, Pieter Dourlein and John Ubbink, not escaped from Haaren prison in the fall of 1943 and made their way to Switzerland. There, they informed the Dutch legation about the Englandpsiel, who then parlayed that information to the British.

Wikimedia CommonsTrix Terwindt, the only woman agent captured by Germany during the Englandspiel, and one of the few who actually manged to survive the war.

The German counterintelligence operation ultimately came to an end on April 1, 1944, but by then the damage had been done, and the incident highlighted the SOE’s shortcomings and the cleverness of German counterintelligence.

Thankfully, the SOE bounced back in the wake of the sige of Normandy on D-Day and the subsequent liberation of Paris that August, which involved the direct cooperation of the SOE and the French Resistance.

Now, the focus had shifted from resistance groups outside of Germany to those within — and if none existed, the SOE was determined to make the Germans believe there were.

Operation Periwig

Wikimedia CommonsA lone worker refuses to give the Nazi salute.

By November 1944, as the war progressed, the Special Operations Executive decided that it needed to establish an organized resistance in Germany on par with the groups already active in many other occupied countries.

In these countries, operating right under the noses of the Nazi leaders in the heart of their evil empire, many different resistance factions existed, made up of laborers, clergymen, and even turncoat German officers. The groups each reported to London and did their best to smuggle information, foment anti-Nazi sentiment, and generally derail Axis operations.

However, no such German groups actually existed. There was certainly real resistance within Germany (such as the White Rose student group and the German officers who famously failed to kill Hitler during Operation Valkyrie), but it was never to the same extent as in the occupied countries.

Naturally, this was partly due to the lack of a sympathetic population: It is much harder to conduct resistance operations without help from the locals. The Gestapo obviously had the strongest grip in Germany itself and few people were willing to risk being interrogated and tortured on merely a suspicion.

So if no full-blown resistance actually existed in the Fatherland, the British would just have to create the illusion that it did.

Wikimedia CommonsHitler’s destroyed bunker after the failed Valkyrie assassination attempt.

In an elaborate smoke-and-mirrors operation named Operation Periwig, the Special Operations Executive used a variety of tactics to convince the German high command that the resistance in their own country was much larger than it actually was. The objective was to have the Nazis waste valuable resources chasing down false leads and potentially encourage the public to take a greater role in the resistance in the belief that the operations were more widespread than they actually were.

These ghost resistance groups were conjured in a number of ingenious ways. Misleading information was intentionally given to known double-agents, fake wireless transmissions were broadcast to Germany, and phony code books and mission plans were planted with the intent that they would fall into Gestapo hands.

The SOE even recruited some German POWs and sent them back to their homeland as agents, without ever informing them that their missions were entirely made-up, in the hopes that whether they turned themselves in or were captured, they would successfully spread word of the phony missions.

Operation Periwig was ultimately considered a failure because what would have been its most important missions were never actually carried out. Plans to fake Catholic resistance to the Nazis were scrapped in the fear that it would only cause the Nazis to crack down on the actual resistance in the Church and an assassination attempt on Hitler was abandoned in the fear it would only make him a martyr in the eyes of the people.

The scope of the operation’s impact and the number of people it convinced to take a more active stand against the Nazis can never be truly known.

The SOE At The End Of World War II

Despite Operation Periwig’s perceived failure, it did mark yet another turning point for the Special Operations Executive as they shifted focus from sabotage and large-scale disruption efforts behind enemy lines to supporting the Allied advance.

Largely, the SOE coordinated with local resistance groups to harass retreating German forces, gathered intelligence on remaining German troop movements and fortifications, and assisted with securing liberated areas and preventing the resurgance of Nazi activity.

They also readjusted their focus on the Far East, redeploying some personnel to Southeast Asia to support resistance movements there against Japanese occupation, particularly in Burma and Malaya.

Once the Germans surrendered in May 1945, the SOE’s European operations rapidly dwindled, with agents either being demobilized or reassigned to other intelligence agencies.

And for years, much of the SOE’s work remained unknown, given the delicate and secretive nature of their operations. However, the lasting impact of their operations, now that much of its extent has been made public, greatly shaped future psychological warfare strategies.

In the years since, there has also been some debate about the morality of specific methods used by the SOE, particularly when it came to targeting civilians during sabotage missions and aligning with resistance groups who didn’t necessarily agree with the Allied cause.

Still, as far as wartime intelligence groups are concerned, the SOE’s influence is undeniable.

After this look at the Special Operations Executive, see some of the most powerful photos of The Blitz endured by Britain at the outset of World War II. Then, experience the Dunkirk evacuation of British forces fleeing the Nazis, which has understandably been dubbed a miracle.