When Kitty Genovese was killed just outside her apartment in Queens, New York, in 1964, dozens of neighbors either saw or heard the prolonged attack, but few did anything to help her.

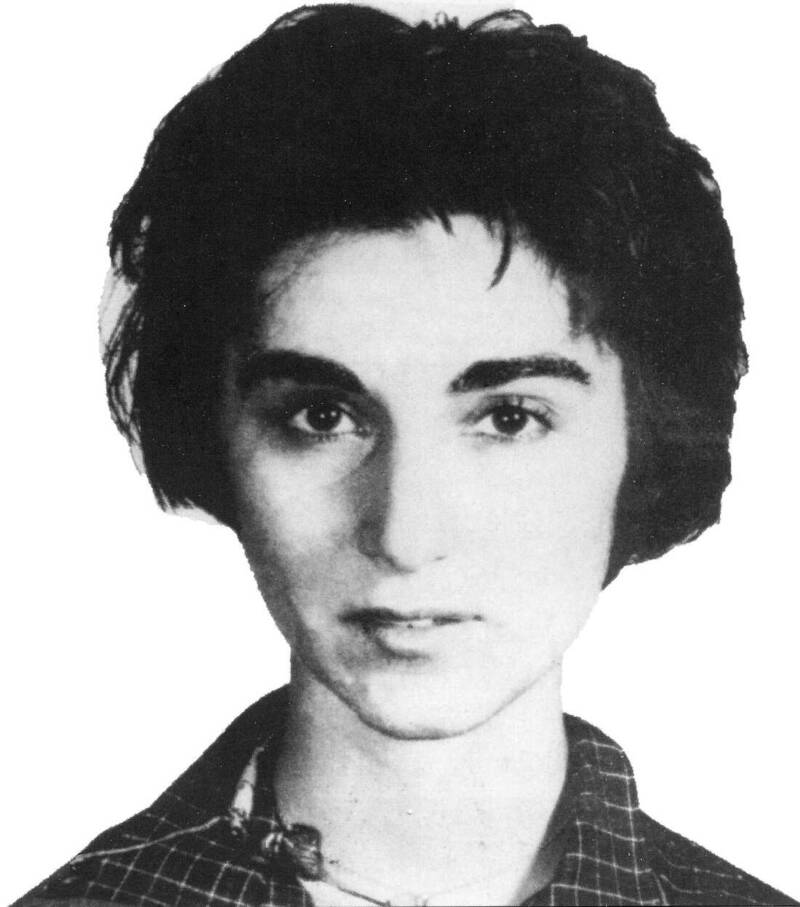

Wikimedia CommonsKitty Genovese, whose murder inspired the idea of the “bystander effect.”

In the early morning hours of March 13, 1964, a 28-year-old woman named Kitty Genovese was murdered in New York City. And, as the story goes, 38 witnesses stood by and did nothing as she died.

Her death sparked one of the most discussed psychological theories of all time: the bystander effect. It states that people in a crowd experience a diffusion of responsibility while witnessing a crime. They’re less likely to help than one single witness.

But there’s more to Genovese’s death than meets the eye. Decades afterward, many of the basic facts surrounding her murder have failed to stand up to scrutiny.

This is the true story of Kitty Genovese’s death, including why the “38 witnesses” claim just isn’t true.

The Shocking Murder Of Kitty Genovese

Born in Brooklyn on July 7, 1935, Catherine Susan “Kitty” Genovese was a 28-year-old bar manager and small-time bookie who lived in the Queens neighborhood of Kew Gardens with her girlfriend, Mary Ann Zielonko. She worked at Ev’s 11th Hour in nearby Hollis, which meant working late into the night.

Around 2:30 a.m. on March 13, 1964, Genovese clocked out of her shift as normal and started to drive home. At some point during her drive, she caught the attention of 29-year-old Winston Moseley, who later admitted he’d been cruising around looking for a victim.

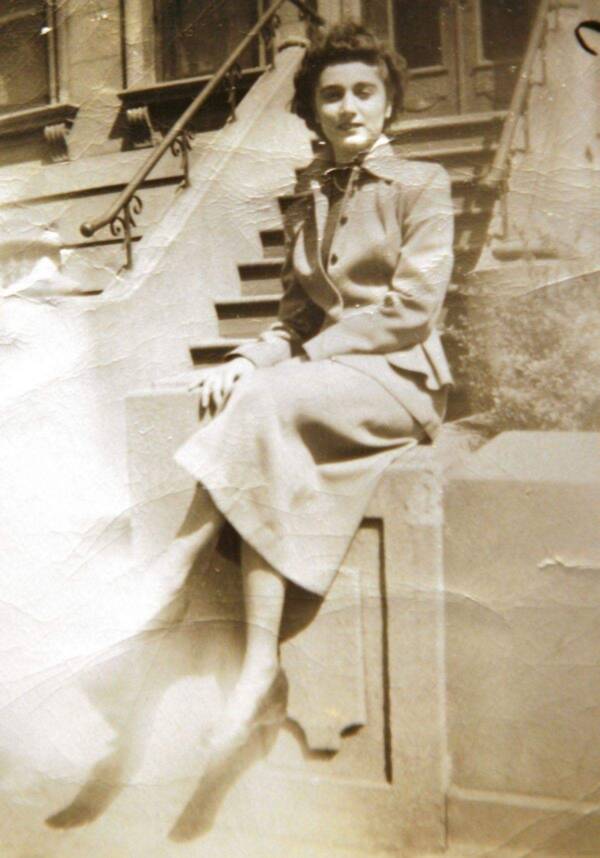

Family PhotoKitty Genovese chose to stay in New York after her parents moved to Connecticut.

When Genovese pulled into the parking lot of the Kew Gardens Long Island Rail Road station, about 100 feet from her front door on Austin Avenue, Moseley was right behind her. He followed her, gained on her, and stabbed her twice in the back.

“Oh, my God, he stabbed me!” Genovese screamed into the night. “Help me! Help me!”

One of Genovese’s neighbors, Robert Mozer, heard the commotion. He went to his window and saw a girl kneeling on the street and a man looming over her.

“I hollered: ‘Hey, get out of there! What are you doing?'” Mozer later testified. “[Moseley] jumped up and ran like a scared rabbit. She got up and walked out of sight, around a corner.”

Moseley fled — but waited. He returned to the scene of the crime ten minutes later. By then Genovese had managed to make it to the rear vestibule of her neighbor’s apartment building, but she couldn’t get past the second, locked door. As Genovese cried for help Moseley stabbed, raped, and robbed her. Then he left her for dead.

Some neighbors, roused by the commotion, called the police. But Kitty Genovese died en route to the hospital. Moseley was arrested just five days later and readily admitted to what he had done.

The Birth Of The Bystander Effect

Two weeks after Kitty Genovese’s murder, The New York Times wrote a scathing article describing her death and the inaction of her neighbors.

Getty ImagesThe alleyway in Kew Gardens where Kitty Genovese was attacked.

“37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police,” their headline blared. “Apathy at Stabbing of Queens Woman Shocks Inspector.”

The article itself stated that “For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law‐abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens… Not one person telephoned the police during the assault; one witness called after the woman was dead.”

A man who did call the police, the article said, dithered as he listened to Genovese cry and scream. “I didn’t want to get involved,” the unnamed witness told reporters.

From there, the story of Kitty Genovese’s death took on a life of its own. The New York Times followed their original story with another one examining why witnesses wouldn’t help. And A. M. Rosenthal, the editor who’d come up with the number 38, soon released a book entitled Thirty-eight Witnesses: The Kitty Genovese Case.

Most significantly, Genovese’s death birthed the idea of the bystander effect — coined by psychologists Bibb Latané and John Darley — also called Kitty Genovese syndrome. It suggests that people in a crowd are less likely to interfere in a crime than a single eyewitness.

Before long, the murder of Kitty Genovese made its way to psychological textbooks across the United States. The 38 people who had failed to help Genovese, students were taught, suffered from the bystander effect. Psychologists suggested that it was more useful to point to one person and demand help than to ask a whole crowd of people for help.

But when it comes to the murder of Kitty Genovese, the bystander effect doesn’t exactly hold true. For one, people did come to Genovese’s aid. For another, The New York Times exaggerated the number of witnesses who watched her die.

Did 38 People Really Watch Kitty Genovese Die?

The common refrain about Kitty Genovese’s death is that she died because dozens of her neighbors didn’t help her. But the actual story of her murder is more complicated than that.

For starters, only a few people actually saw Moseley attack Genovese. Of those, Robert Mozer shouted from his window to scare the attacker off. He claims he saw Moseley flee and Genovese rise back to her feet.

By the time Moseley returned, however, Genovese was largely out of sight. Though her neighbors heard shouts — at least one man, Karl Ross, saw the attack but failed to intervene in time — many thought it was a domestic dispute and decided against intervention.

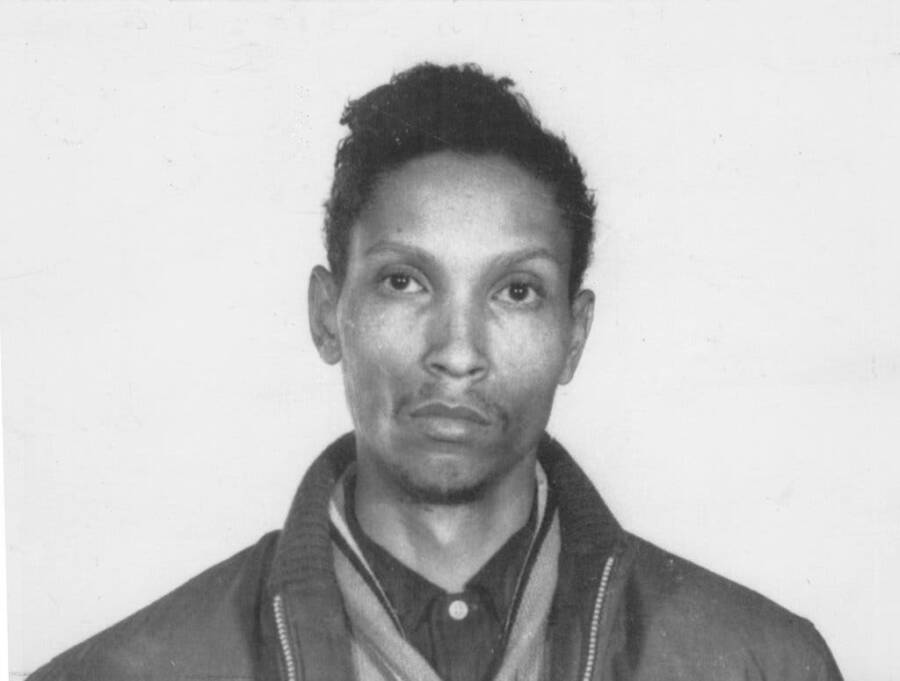

Public DomainWinston Moseley later admitted to killing three other women, raping eight women, and committing between 30 and 40 burglaries.

Significantly, one person did intervene. Genovese’s neighbor Sophia Farrar heard screams and raced down the stairs without knowing who was there or what was happening. She was with Kitty Genovese as Genovese died (a fact not mentioned in the original New York Times article.)

As for the infamous 38 witnesses? When Genovese’s brother, Bill, investigated his sister’s death for the documentary The Witness, he asked Rosenthal where that number had come from.

“I can’t swear to God that there were 38 people. Some people say there were more, some people say there were less,” Rosenthal responded. “What was true: People all over the world were affected by it. Did it do anything? You bet your eye it did something. And I’m glad it did.”

The editor likely got the original number from a conversation with Police Commissioner Michael Murphy. Regardless of its origins, it hasn’t stood the test of time.

After the death of Moseley in 2016, The New York Times admitted as much, calling their original reporting of the crime “flawed.”

“While there was no question that the attack occurred, and that some neighbors ignored cries for help, the portrayal of 38 witnesses as fully aware and unresponsive was erroneous,” the paper wrote. “The article grossly exaggerated the number of witnesses and what they had perceived. None saw the attack in its entirety.”

Since Kitty Genovese’s murder occurred more than 50 years prior to that statement, there’s really no way to know for sure how many people did or didn’t witness the crime.

As for the bystander effect? Though studies suggest that it exists, it’s also possible that large crowds can actually spur individuals to take action, not the other way around.

But Rosenthal has a strange point. Genovese’s death — and his editorial choices — did change the world.

Not only has Kitty Genovese’s murder been portrayed in books, movies, and television shows, but it also inspired the creation of 911 to call for help. At the time Genovese was killed, calling the police meant knowing your local precinct, looking up the number, and calling the station directly.

More than that, it offers a chilling allegory about how much we can depend on our fellow neighbors for help.

After learning the full story behind the murder of Kitty Genovese and the bystander effect, read about the seven strangest celebrity murders in history. Then, take a look at photos of old New York murder scenes.