In 1932, a reclusive hunter named Albert Johnson opened fire on Canadian police — and then tried to flee into the icy mountains of the Northwest Territories. To this day, no one knows why.

Wikimedia CommonsPhotos of Albert Johnson’s dead body, taken by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

On Dec. 31, 1931, Royal Canadian Mounted Police officers Alfred King and Joe Bernard returned to the cabin of Albert Johnson, deep in the forests of Canada’s Northwest Territories.

They had previously tried to contact the reclusive hunter a few days earlier, but they were unsuccessful. So they made the 80-mile trek from the nearest town yet again. And this time, they brought a search warrant.

The original plan was that Johnson would just be questioned and possibly corrected for trapping in a restricted area. Without proper signage, it would have been an easy mistake for a relative newcomer to make.

Had Johnson answered the door and their questions, that could have been the end of the story. Instead, Albert Johnson’s still-unexplained actions earned him immortality as the mysterious “Mad Trapper” of Rat River.

Who Was Albert Johnson?

No one knew much about Albert Johnson. To this day, no one even knows if that was his real name.

He was quiet. On the rare occasions when he spoke, he was described as having a faint Scandinavian accent — marking him as an immigrant likely from Sweden or Denmark. Or perhaps he was a child of immigrants who had never mastered English.

He stood at nearly 5’10”, with blue eyes and brown hair, and was estimated to be about 35 years old. His face was prematurely weathered.

Wikimedia CommonsSide view of Albert Johnson’s body.

Almost no one who’d met Johnson in the months he’d lived near Rat River before his encounter with the Mounties had much to say about him.

Johnson was new to the area, as many people were. During the Great Depression, fur trading had proved one of the few lucrative professions.

Newcomers from South Dakota and Nebraska had come to seek their fortunes, or at least their food funding, in Arctic fox, mink, and other furs. But these new arrivals were often ignorant — both of local niceties and the dangers of winters — an attribute liable to get them in trouble.

Start With A Bang

When the Mounties knocked on Johnson’s door, they intended to follow up on reports that he had been poaching along First Nations’ trap lines.

This time, however, after announcing themselves and receiving no response, they tried to force the door open. Johnson responded by opening fire — shooting King through the door and knocking him into the snow.

Bernard and the other constables with him tended to King’s wounds and made a desperate trek back to civilization to get him to a doctor.

Fortunately, King survived. Then, Bernard and a much larger posse — consisting of nine Mounties and 42 dogs — headed back into the forest to teach Albert Johnson a lesson.

Upon their arrival in early January, the police were no longer willing to take chances on the “Mad Trapper’s” respect for the law. They circled the cabin, warmed several sticks of dynamite, and threw the explosives onto the roof.

The resulting blast echoed across the area, shaking snow down from the trees as Johnson’s cabin collapsed in on itself. The Mounties prepared to close in and search the rubble for the dead or wounded outlaw. That’s when Johnson emerged from within the remains, and opened fire.

Wikimedia CommonsAlbert Johnson’s destroyed cabin, dynamited by Mounties.

How Johnson became familiar with siege tactics is unknown, but it was later discovered he had dug a deep trench into the bottom of his cabin, using it as a temporary shelter from the explosion.

A 15-hour firefight broke out, lasting well into the early morning hours despite subzero temperatures. Although no one was wounded this time, the Mounties determined that they were out of their depth and retreated to the closest town to gather reinforcements.

Between their departure and their return to Johnson’s ruined cabin a few days later on Jan. 14, 1932, a massive blizzard struck the area, slowing their progress, and, they assumed, the progress of any normal suspect on the run.

Johnson, a stranger to these parts, had no permanent shelter to protect him, an almost certain death sentence under these conditions.

However, the Mounties discovered that not only had Johnson survived, he had also made a break for it — heading further into the icy wilderness, using the frozen Rat River like a paved roadway.

An Impossible Chase

Using dogsleds, the Mounties took off after Johnson. The snow was deep, and it was cold even in the daylight. Meanwhile, newspapers and radio programs across Canada kept the public informed of the story.

It was presumed, logically, that no one could survive in these conditions, especially someone with limited supplies, no permanent shelter, and the clothing on their back. Just breaking through the ice of a frozen lake or river could have been lethal in a matter of minutes.

But, as the chase stretched on for weeks and authorities were no closer to capturing Johnson, the “Mad Trapper’s” legend grew.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Mounties who pursued Albert Johnson. 1932.

When the Mounties next spotted Johnson on Jan. 30, he was holed up inside a thicket of brush beside a cliff face. Hearing his pursuers climbing down into the canyon from above him, Johnson opened fire.

Gunshots echoed back and forth before Johnson dove behind a fallen tree, as if he was shot. The fighting stopped. They called for Johnson to give himself up and received no response.

They waited. Two hours passed in the biting cold. If Johnson was still alive down there, Constable Edgar Millen reasoned, they had to act quickly before he could slink off into the storm. Although all the officers were nervous, one of the posse members agreed to join Millen on his descent.

They had only made it so far when the first shot exploded into the snow beside the Mounties, shattering the winter silence. Blinded by the snow, both officers opened fire on where they thought Johnson was hiding.

Johnson fired two more times, so fast, it sounded as if the two shots had been simultaneous. Millen spun around and collapsed face-first in the snow. Riddell and the other Mounties pivoted from assault to rescue, dragging Millen out of Johnson’s firing line with the help of the sled dogs.

When they stopped to inspect his wounds, however, it was too late. Despite the poor visibility, Millen had been struck directly in the heart, dying almost instantly. Afterward, police swore they heard Johnson cackle.

Taste For Blood

By the time the Mounties regrouped, resupplied, and sent Millen’s body back to civilization, Johnson had vanished once again. An inspection of his hiding place along the opposite canyon wall uncovered two things.

One, he was apparently unwounded, having utilized a makeshift fox hole created by several overlapping spruce trees. Two, he had climbed the sheer cliff behind him with minimal gear, giving him yet another head start and indicating that he intended to walk across the mountains.

When the Mounties followed after him, this time they called for backup from the air. Using a newly introduced monoplane, the aerial assistance finally provided the police with the advantage that they needed.

Whereas, before, the Mounties had been limited by their constant need to resupply both for themselves and their dogs — a trip that could take a few days back and forth each time — the plane could not only reduce that time greatly, it could also observe Johnson’s movement from the air.

Wikimedia CommonsMounties boarding a plane in pursuit of Johnson. 1932.

While this undoubtedly helped tip the balance in the police’s favor, the conditions on the ground were also taking a toll on Johnson.

For the several weeks he’d been on the run, the temperature had never risen above zero. He could not hunt game with his gun, for fear of alerting authorities. And between the grueling pace and the hard conditions, he was suffering from frostbite and starvation.

The Final Fight

Following an aerial sighting of Johnson emerging on the other side of the mountains, a group of Mounties arrived by plane in early February 1932.

Another group of men followed behind Johnson, hoping to cut off all chance of retreat. Slowed by snow and fog, the two groups ran into each other before finding anything other than the “Mad Trapper’s” trail.

On Feb. 17, the search party was as surprised as their suspect was when the two ran into each other on the frozen Eagle River.

The officers opened fire, spreading out and circling Johnson to get multiple lines of fire on their opponent. Johnson, for his part, dived into a snowbank, attempting to use it for cover.

He shot another Mountie — severely wounding but not killing him — but between the hunger, frostbite, exhaustion, and superior numbers, the “Mad Trapper” had finally met his match.

The lead officer shouted for Johnson to stand down after he had been shot three times, but he refused and continued firing. It was only when he stopped shooting long enough for the officers to approach that they discovered he was dead — shot through the spine during the fight.

While that would have been the end of things in most cases, Albert Johnson defied expectations even in death.

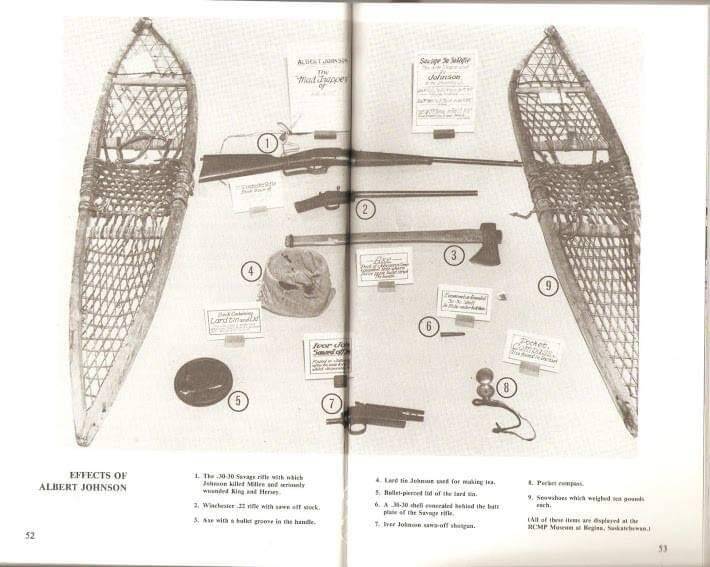

RCMPAlbert Johnson’s possessions, kept at the Royal Canadian Mounted Police Museum.

A careful search of Albert Johnson’s body uncovered no form of identification, photographs, or personal mementos. On top of that, none had been found at the ruins of his cabin.

Instead, in addition to his rifles and snowshoes, the Mounties found more than $2,000 in Canadian and American currency, a few pearls, several kidney pills, and a bottle full of gold teeth, which didn’t match him.

More Questions Than Answers

An examination of Johnson’s body provided few other clues. Likely in his 30s, his hard lifestyle had left him prematurely weathered.

He had no tattoos or major identifying marks. It was unlikely that he ever had major surgery. His fingerprints did not match any in police records.

The cops may have stopped the “Mad Trapper,” but now they had no idea who he was or what he had been doing in the wilderness.

Before burial, police took several pictures of Johnson’s corpse. In the images, his face is frozen in a contorted expression of pain and rage.

The Mounties distributed the images around the country, hoping someone would recognize the man. Eventually, a few years later, someone did.

In 1937, trappers from the town of Dease Lake wrote to the Mounties, saying the picture of Albert Johnson published in a detective magazine looked like a man they had known as Arthur Nelson in the 1920s.

What’s In A Name?

A decade earlier, Nelson had worked as a trapper near Dease Lake. A quiet man with a faint Scandinavian accent, they thought he’d come from Denmark but he never confirmed it.

He loved local legends about lost mines and seemed interested in seeking them out. He didn’t talk much, and he would never allow another person to walk behind him on a trail.

Asked whether he had ever seemed violent, witnesses could only recall a single incident. One night, joined by a group of other men by the campfire, Nelson had set his new rifle up against a tree.

One of the other hunters stood and picked it up, complimenting him on its construction, only to turn around and find Nelson standing directly behind him. He had not thought much of it at the time, but if Nelson really had been the “Mad Trapper,” he wondered now if Nelson might have killed him.

Someone else remembered Nelson purchasing six boxes of kidney pills from a local store before leaving the area, the same type later found on Johnson.

Unfortunately, it seemed that Arthur Nelson had also come and gone from thin air. No more useful information was available for Nelson than Johnson, leading Mounties to guess that name was yet another alias.

Sadly, this is about all that is officially known about the identity of the “Mad Trapper.” Multiple people have been suggested as solutions to the mystery, but recent DNA testing has ruled out many suggested suspects.

Per the same genetic research, Johnson was later revealed to likely be Scandinavian by descent. However, his tooth enamel hinted at a corn-heavy diet, suggesting he’d spent time in the Midwestern United States.

But even if we can’t find out who the “Mad Trapper” really was, can we at least make any guesses about what he was up to and where he’d learned his combat and survival skills?

Lingering Questions And Popular Theories

One of the most outlandish theories holds that Albert Johnson was a hitman. Based on his skill with firearms and the large amount of money found on him, proponents of this theory suggest that Johnson had traveled into the Northwest Territories to hide out after a successful job.

While there’s little else to indicate Albert Johnson was an assassin, the amount of money he was carrying might actually make sense for his profession. Fur trapping was a very lucrative trade, with some trappers able to make as much as $5,000 during the winter.

Slightly less outlandish is the assertion that Johnson was a serial killer or, at least, a particularly murderous claim jumper.

In addition to the gold teeth and fillings found on his body, fans of this theory point to a strange number of deaths in areas frequented by Arthur Nelson and Albert Johnson, with a number of remote trappers and miners turning up dead, some found missing their heads.

While this theory suffers from a lack of direct evidence, it would explain the otherwise mysterious gold teeth found on Johnson’s body — and serve to answer another question.

If the man known as the “Mad Trapper” was a recluse trying his best to leave human society, why was he always living — both as Johnson and Nelson — just on the outskirts of populated areas? In the Northwest Territories, it would have been easy for him to completely disappear into the wilderness.

If instead, Johnson was preying on other hunters, trappers, miners, and outdoorsmen, killing them for their territory and possessions, his choice of location makes much more sense.

Still, no one could recall Johnson selling off other people’s possessions or even having much success with his mining hobby. Unless, of course, he had succeeded and told no one.

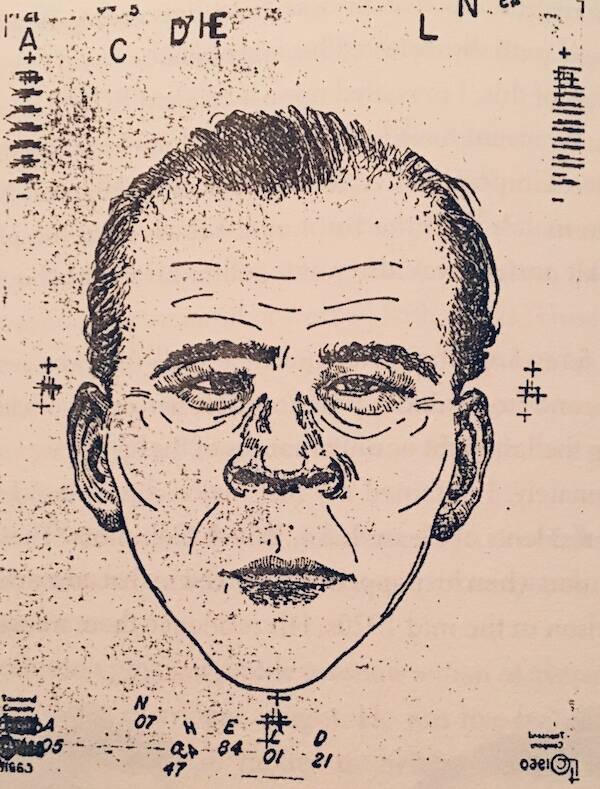

Alaska State TroopersIdentikit made from Johnson’s death photos by Alaska State Troopers. Circa 1930s.

Another plausible explanation is that Johnson had discovered the gold he had been searching for, finding one of the lost mines of local legend.

In this theory, everything Johnson did — from harassing local natives to shooting at the Mounties — was either intended to scare people away from his territory and to hide his valuable discovery from anyone who might want a share, especially the government.

While interesting, the problem this presents is that, had Johnson discovered a great quantity of gold, you would think at least some of it would have been present on his body or in the ruins of his cabin — unless Johnson had stashed his findings somewhere else.

Regardless, until someone locates the potentially missing precious metal, this explanation does not have much to stand on.

Working off the repeated references to Johnson’s accent and the claims he came from Sweden or Denmark, some researchers have posited that the “Mad Trapper” was an illegal Scandinavian immigrant who fought the police to avoid potential deportation.

Another theory held that he was a World War I draft dodger who had fled from Scandinavia and would face criminal prosecution and harsh punishments in the event that he was returned to his homeland.

Given Johnson’s estimated age in 1932, he would have been in his late teens or early twenties during World War I. If he was from the United States — as the data from his teeth suggests — he would almost certainly have been subjected to the draft of 1917 to 1918 and seen service in Europe.

If he served in World War I, it would explain large amounts of his training in firearms and survival techniques. It might also, supporters say, explain just what he was doing out in the wilderness.

Although millions of soldiers came back from that war with what we would today recognize as PTSD, in the aftermath of World War I, “shell shock” and “battle fatigue” were seen as new and unknown psychological epidemics.

It is conceivable that Johnson, fresh from the battlefield, could not adjust back to his civilian life and so abandoned it to live in the woods. When, one day, a group of armed men knocked on his door, Johnson’s hyper-vigilance kicked in and he started shooting.

If this version were true, it would make the entire situation a tragedy, a modern morality play about the place of veterans in our society.

Still No Satisfying Answers In Sight

Wikimedia CommonsA sign remembering the legendary story of Albert Johnson in Aklavik, Canada.

However, as much as any of these options are possible, it is also plausible that Albert Johnson was exactly what he seemed: a quiet and private fur trapper with little love for other humans who just wanted to be left alone.

Even the “mysterious” trench dug into the bottom of Johnson’s cabin — a favorite piece of evidence for those preferring the World War I veteran theory — can be interpreted with a simpler explanation. It may have been a root cellar or a primitive refrigerator, common features in off-grid log cabins.

The only thing this does not explain, apart from the teeth, is why Johnson shot at the Mounties in the first place. But, if Johnson being an assassin is a fair theory, so is the possibility of him suffering from severe mental illness.

In the decades since his death, the mysteries Albert Johnson left behind have captivated true crime aficionados. With no obvious answers on the horizon, those might be mysteries we have to live with for a long time.

Whatever Johnson was hiding — and it certainly seems, by his violent reaction to the Mounties’ arrival that he was hiding something — it was a secret worth dying for. In all likelihood, he took that secret to the grave.

If you liked this story about the Mad Trapper, you might also enjoy learning about the family who survived alone in the Siberian wilderness for 42 years. Also, consider reading about some of history’s strangest deaths ever recorded.