A Brief Respite: Moral Treatment

Source: Blogspot

Conditions at Bedlam, and at many of the other hellholes dotted around England and America, motivated a sea change in the treatment of the mentally ill. For example, the belief grew that mentally ill people should actually receive treatment, which made for a nice change of pace. Spearheaded by Quaker reformers, who had spent the previous century opposing witch trials and would spend much of the next agitating for the abolition of slavery, the concept of “moral treatment” came into focus for the first time.

The philosophy of moral care was, basically, Do Unto Others. Patients were to be housed in large, spacious estates, far from the city, where they would be allowed recreation, privacy, and adequate food. Staff at these facilities would assign such duties as patients seemed able to handle, such as sweeping the hallway on their floor or tending the community garden, and family visits would be encouraged, rather than forbidden.

Visits from abusive members of the public, as had been common at Bedlam, would not be permitted. Moral treatment gradually caught on across the northeastern United States, with dozens of asylums built in the early 19th century.

The Decline and Fall of the Moral Model

Source: Blogspot

Of course, it was too good to last. In a very real way, moral treatment was a victim of its own success. As it routinely produced a 65-percent remission rate among psychotic patients (an enviable 5-year prognosis, even today), moral treatment facilities came to be seen as a panacea for every social ill, which led to a rapid influx of mental patients in every state that had adopted the moral model.

Unfortunately, state legislatures didn’t feel the need to invest money in the facilities they were packing to the brim with every vagrant in Philadelphia and Boston, so the very heart of moral treatment—space, privacy, personal attention—became impossible in the newly overcrowded asylums. Even worse, moral treatment was coming to be seen as a cure for run of the mill criminality.

As bad as it is for a double-occupancy room to hold five people, imagine how much worse it is when three schizophrenics are housed with a burglar and a rapist. Gradually, by the end of the 19th century, moral treatment centers had become the crowded madhouses they had originally been intended to replace.

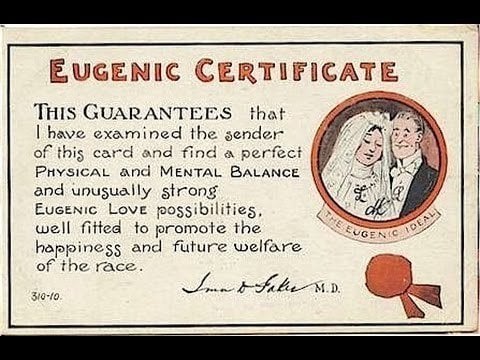

Eugenics

Source: Mashpedia

It didn’t help that moral treatment, being essentially religious, had made a powerful enemy. Physicians, eager to medicalize mental illness and put a stop to the emetics and bloodletting that were still being used at moral asylums, campaigned to redirect the focus of state healthcare systems onto a firm scientific grounding.

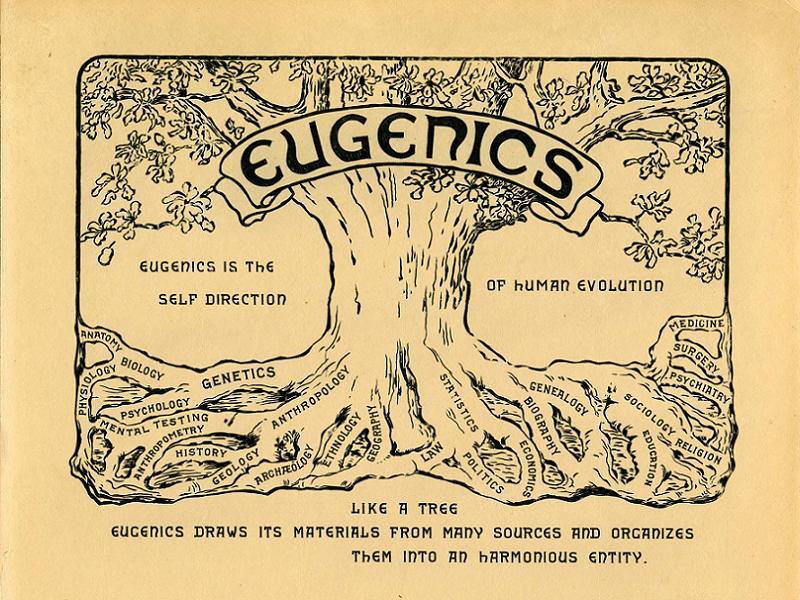

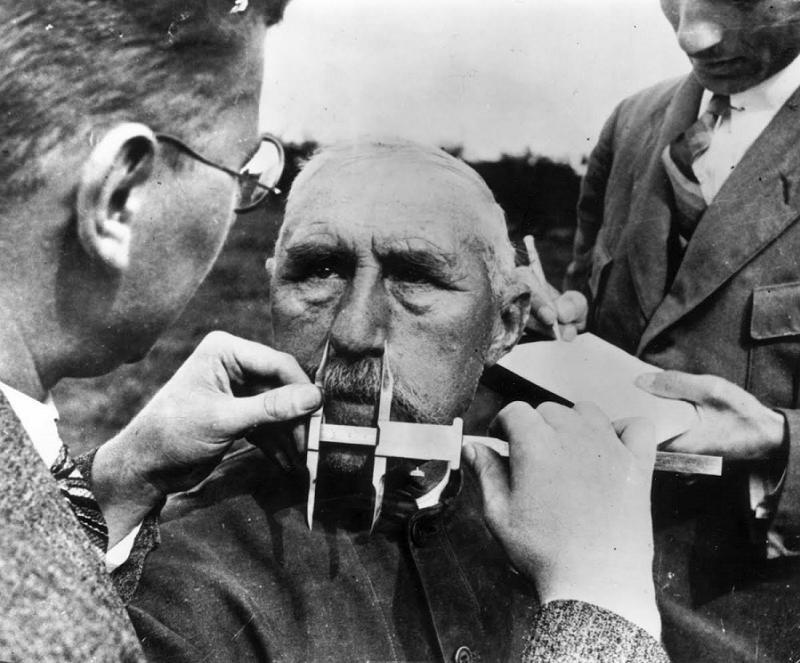

Which would have been great, except that medical science was going through its Kafkaesque phase just then, what with the germ theory of disease having just been thought of and all kinds of quack approaches (sorry, chiropractors, but you know it’s true) being favored. Near the end of the century, Francis Galton, a distant cousin of Charles Darwin, dramatically misunderstood his cousin’s theory and coined the term “eugenics” for the kind of large-scale human engineering he had in mind.

What could possibly go wrong?

The notion developed that mental illness arose from a “weak germ line,” and that “congenital idiocy” can be cleansed from the human genome via a liberal course of sterilization. So sweeping was the eugenics fad that 30 states (the worst 30; you know who you are) adopted compulsory sterilization laws during the early 20th century, and no less a jackoff than Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes ruled that such laws passed constitutional muster in the 1925 case of Buck v. Bell.

In that case, a former foster child named Carrie Buck was committed to an insane asylum in Virginia after either her foster father or brother raped her. Actually, they both probably raped her, but there’s no telling who fathered the baby. Buck’s mother had been considered mad, which the foster family found really convenient when it came time to lock her up.

Under Virginia law, Carrie Buck could be released from custody if she consented to a surgical sterilization. Her case, that she wasn’t crazy and anyway to hell with you, didn’t go down well with the courts. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Holmes wrote:

We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence.

It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes… Three generations of imbeciles are enough.

Eventually, around 30,000 American citizens would be forcibly sterilized, mainly for being black, Native American, or poor white trash. Even more eventually, World War II happened, and all the eugenics enthusiasts decided to shut the hell up for once after the liberation of Dachau.