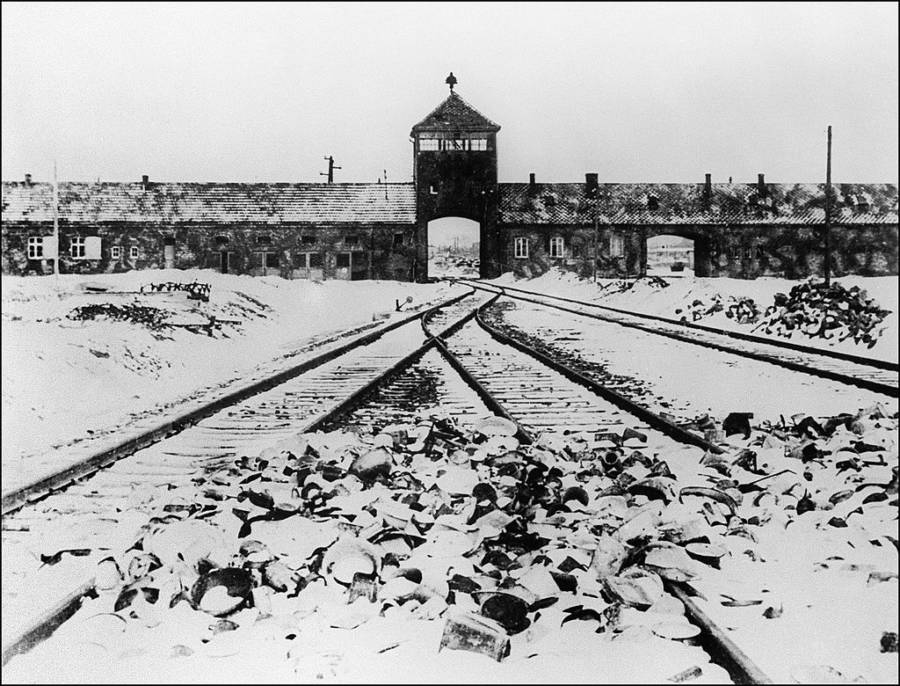

AFP/AFP/Getty ImagesAuschwitz concentration camp

They thought they would find about 5,000 of them.

The year was 1999 and the team was tasked with gathering information on each persecution site established by the Nazis in World War II. Team members would then compile their findings into the first comprehensive record of each forced labor camp, military brothel, ghetto, POW detention center and concentration camp the Nazis introduced and ran.

5,000 sites seemed right. 5,000, after all, is a lot.

But as the researchers began their search, which they conducted at the behest of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, they realized they had more than slightly underestimated the scope of this undertaking.

By 2001, they had already uncovered 10,000 sites.

Today, the “Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos” has documented 42,500 areas where Nazis imprisoned, tortured and killed, according to The Times of Israel.

“You could not turn a corner in Germany (during the war) …without finding someone there against their will,” Geoffrey Megargee, the project’s leader, said.

Not only did the magnitude of sites uncovered make the project difficult for researchers, they also had to contend with the reality that these events had taken places decades ago — and that many people would much rather forget about them.

Thus, researchers decided that the final tally would only include camps whose existence multiple witness testimonies and official documents had verified.

In search of those criteria, historians took nontraditional measures.

One man, Herman Weiss, began his search as a kind of repentance for his father’s own involvement in Nazi efforts.

Weiss turned his attention to an area not often studied – the region of Silesia – and found a record of a Commander Pompe who had a son named Herbert. He then called every living Herbert Pompe in Germany before getting in touch with the Commander’s daughter-in-law.

This led him to more files, which eventually allowed him to corroborate the existence of about 24 sites for the encyclopedia – six of which had never been discovered before.

Many of the other researchers have personal ties to the sites. Some of them were held there themselves, and provided testimony. One woman’s uncle had been imprisoned at a Jewish camp that, until this project, had been believed to be a POW prison.

Another woman’s uncle had orchestrated the deaths of more than 20,000 Jews in an area where most of the prisoners were women and children.

Her name is Katherina von Kellennbach and she joined the research team while uncovering the extent of her uncle’s crimes.

“There’s no way you walk out at 5:00 p.m. as a human being,” she said of her days sifting through archives.

The seven-part encyclopedia is set to be completed in 2025. And though its contributors have uncovered vast swaths of new information, their most telling discovery is this:

Even experts have underestimated how much we still don’t know about the Holocaust. There is so much information left to uncover, and even more that has likely been lost forever.

Next, take a look at 44 photos of perseverance in the Holocaust. Then read about what kinds of people think the Holocaust didn’t happen and why they think that way.