Tomás de Torquemada was responsible for over 2,000 deaths during the Spanish Inquisition, all in the name of keeping Catholicism alive in Spain.

Getty ImagesTomas de Torquemada

In 15th century Spain, there lived a man named Tomas de Torquemada. Though his name is often lost in the pages of history, he had a hand in almost every major event that occurred in Spain during his lifetime. Had it not been for Torquemada, Columbus may never have sailed to the Americas, the Spanish Inquisition may never have happened, and, perhaps most importantly, 2000 Spanish citizens would never have lost their lives.

In the mid-1400s, it was either get with the Catholic Church or get out.

During the Spanish Inquisition, thousands of Jewish and Islamic people were thrust out of the country with just the clothing on their backs, after being dubbed heretics for their late, panicked conversions to Catholicism.

In order to ensure that the heretics were being properly expelled from their homes, the Pope appointed inquisitors to investigate each specific case. Though the inquisitors had been given relatively lax rules regarding what they could and could not do, one inquisitor in particular took his job a little too far.

Getty ImagesTomas de Torquemada with Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand.

Tomas de Torquemada was a force to be reckoned with. During his time as an inquisitor and later as the Grand Inquisitor, Torquemada was responsible for the brutal deaths of over 2,000 people.

Born into a humble family from Valladolid in 1420, Torquemada was destined for a religious life. His uncle was a respected cardinal and celebrated theologian, whose mother had converted from Judaism to Catholicism before he was born. As a child, Torquemada was instilled with religious orthodoxy and grew up to be a zealous practitioner.

As a young man, Tomas de Torquemada became a Dominican friar, at the monastery of Santa Cruz at Segovia. There, he met the young Spanish Princess Isabella, who would one day rule the country.

The two discovered they had a lot in common, and for the rest of their days remained the closest of allies and confidants. In fact, it was at Torquemada’s behest that Isabella marry King Ferdinand of Aragon, to consolidate their kingdoms.

Had he not brought the two together, the world (both Old and New) would quite possibly be dramatically different.

When the Spanish Inquisition was established, Isabella relied on her advisor to help her. Of course, Torquemada was willing to help, as his religious stance was firmly pro-Catholicism. So, when the pope was looking for those willing to stand up for their beliefs and fight for their religion, and lead the inquisitors on their quest to rid Spain of heretics, Torquemada was naturally Isabella’s first pick.

It was also her biggest mistake.

With his newfound power, Tomás de Torquemada became a furious leader, forcing those who had converted to Catholicism for reasons he had deemed unfit – such as fear of retaliation had they not – to wear garments that marked them as condemned. The garments bore images of hell’s flames, demons, dragons or snakes, and served as an alternative to imprisonment.

Additionally, heretics would be subjected to something known as the “water cure,” similar to what we now call waterboarding. Those victims of the water cure torture were often women, as they were seen as weaker and more likely to confess their sins when subjected to pain.

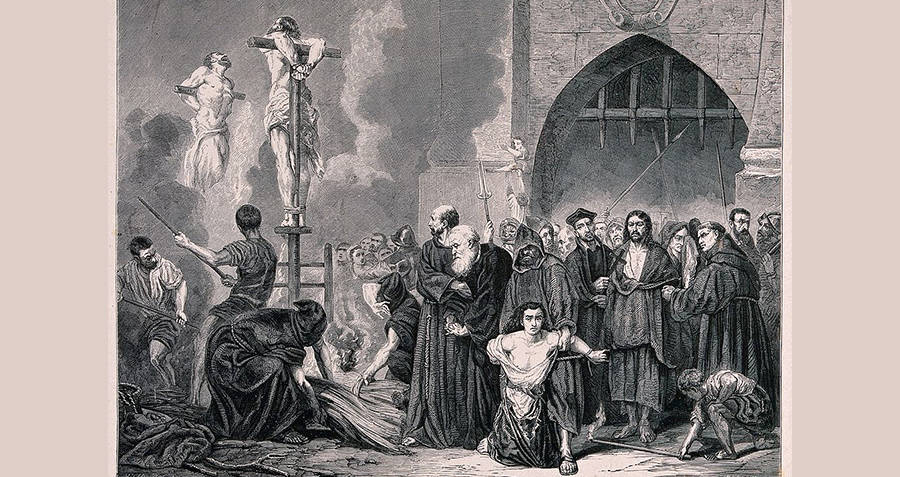

Other victims would be burned alive in “auto-da-fe” ceremonies, which literally translates to “act of faith.” They would be given the opportunity to confess to avoid being burned alive – though that just meant that they would be garroted before their bodies were burned.

Wikimedia CommonsHeretics being punished during the Spanish Inquisition.

He also oversaw the expulsion of 40,000 Jews from Spain, taking with them only what they could carry. Those who weren’t forced out of the country were forced into Christianity, receiving nonconsensual baptisms so they could remain in the country. Any of the forced converts who were seen practicing their Jewish traditions were immediately targeted by Torquemada and his inquisitors.

However, as most of the inquisitors drew the line after expulsion or forced baptism, Torquemada went further. Under the guise of ridding Spain of the heretical religious zealots that were besmirching its name, Torquemada oversaw the executions of 2,000 people. Reports of Torquemada’s crimes were recorded by Hernando del Pulgar, Queen Isabella’s personal secretary.

Though the Inquisition extended far beyond Torquemada’s death, the bulk of the misery occurred under his watch. Eventually toward the end of his life, complaints began to filter back to the Pope. Torquemada claimed that his retirement to the St. Thomas Aquinas monastery in Avila was due to his ailing health, though some historians claim it could have been due to the complaints against his terrifying reign.

After fifteen years as Grand Inquisitor for Spain, Tomas de Torquemada died in the monastery in Avila. As most friars were, he was interred there within its walls.

In 1832, his tomb was ransacked, just two years before the official end of the Inquisition. His bones were stolen and ritually burned, made to appear as if an “auto-da-fe,” or “act of faith” took place.

Whether the act of faith was honoring his memory with a ritualistic cremation or ridding the earth of a devil of a man once and for all, the world may never know.

After reading about Tomas de Torquemada, check out the most painful torture devices used in medieval times. Then, check out the worst witch trials ever to take place in Europe.