WIllie Francis was sentenced to death by electric chair, but a drunken executioner's misstep resulted in a painful shock, but a miraculous survival.

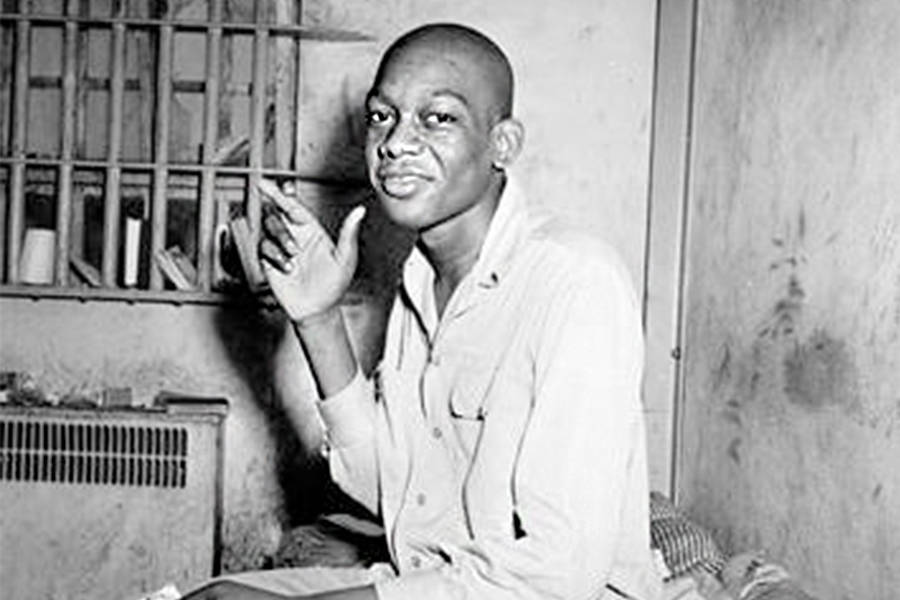

Wikimedia Commons Willie Francis, the “teenager who was executed twice.”

On May 3, 1946, Willie Francis, a 17-year-old black teenager prepared for his final moments on earth. As he was strapped into “Gruesome Gertie,” Louisiana’s electric chair, too scared to say his goodbyes, Francis just clenched his fists and awaited the inevitable moment when the switch would be flicked. But, when the moment came, something went wrong.

Miraculously, Francis survived.

Little did he know that his survival would start a year-long court battle that would take his case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, one that would ultimately fail and brand him ‘the teenager who was executed twice.’

The First Execution

Wikimedia CommonsThe electric chair that failed to execute Francis, known as “Gruesome Gertie.”

After his first botched execution, Francis gave a rare insight into what it felt like to have electricity surge through his body.

“The best way I can describe it is: Whamm! Zst!” he said. “It felt like a hundred and a thousand needles and pins were pricking in me all over and my left leg felt like somebody was cutting it with a razor blade. I could feel my arms jumping at my sides … I thought for a minute I was going to knock the chair over…I think I must have hollered for them to stop. They say I said, “Take it off! Take it off!’” I know that was certainly what I wanted them to do—turn it off.”

After the chair failed, it was discovered that “Gruesome Gertie” had been set up incorrectly. At the time, the electric chair was portable and was transported by truck from jail to jail in Louisiana to perform executions. The two executioners responsible – Captain Ephie Foster and an inmate named Vincent Venezia, who worked as an assistant electrician within the Louisiana prison system – had been drinking the night before.

Despite their misstep, the executioner was furious at Francis. Foster had said “Goodbye, Willie,” as he flicked the switch. When Francis was still breathing minutes later, Foster shouted, “I missed you this time, but I’ll get you next week if I have to use a rock!”

But, Willie Francis wasn’t executed the next week.

Instead, he was suddenly thrust onto the front page of the news. His survival was viewed by many as an act of God. Could Louisiana now, in good faith, put this black teenager to death? The media coverage also drew unwanted attention towards the way African Americans were treated in the Louisiana court system. Francis, who was poor, black, and not yet an adult (like many inmates) had few legal protections available to him.

Francis’ Crime

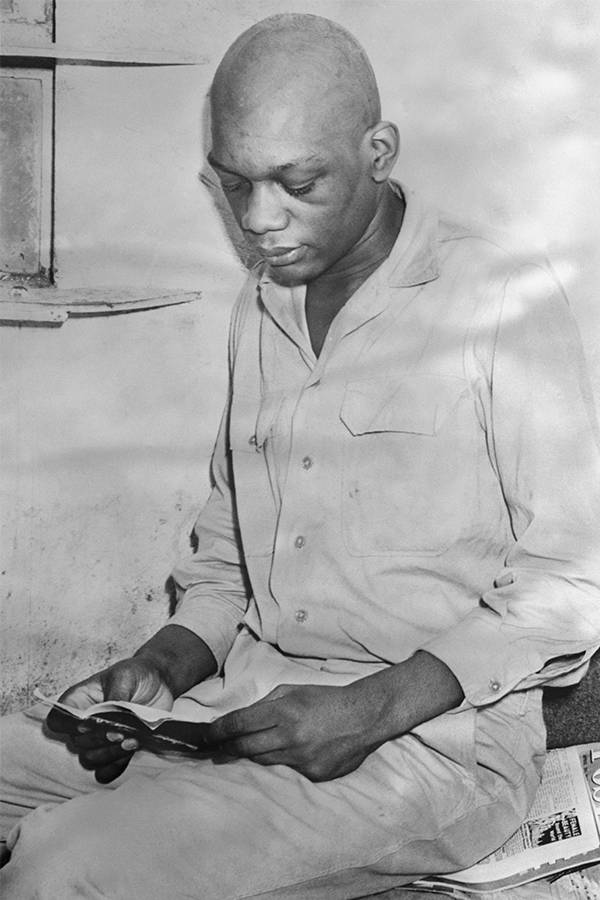

Bettmann/Getty ImagesWillie Francis reading in his cell.

Sixteen months earlier, in November of 1944, someone shot Andrew Thomas, a popular white pharmacist in Francis’ hometown of St. Martinville, La. Two months after the murder, with no suspect, St. Martinsville’s sheriff, E. L. Resweber, called upon the Chief of Police in Port Arthur to arrest “any man” in order to put this case to bed. A few weeks later they had their man – Willie Francis.

Francis, who was visiting one of his sisters in Port Arthur, was arrested on suspicion of being a drug dealer’s accomplice. But when the police could not connect him to the drug dealer, they began questioning him about the St. Martinsville murder. The police allegedly found the murdered pharmacist’s wallet and identification card in Francis’ possession.

Within minutes the police had a signed confession from Francis for the murder, followed by a second confession the next day. The police denied any coercion, though some of the words used were most likely the result of dictation from a policeman.

Three weeks after his arrest, Francis found himself in front of a grand jury of white men. He pleaded not guilty, but his white lawyers tried to reverse his plea and then refused to make an opening statement. Appallingly, Francis’ lawyers did not cross-examine witnesses even though the evidence against Francis was dubious at best.

A lot of mystery surrounded the murder weapon. Francis had supposedly stolen the gun from the Sheriff’s deputy, but the deputy had reported the gun missing two months before the murder. Furthermore, the gun wasn’t examined for fingerprints, the bullets found in Thomas’ body weren’t matched with those from the gun, and suspiciously, the gun and bullets were lost before the trial while en-route to the FBI for analysis.

In fact, the gun linked the deputy to the murder. He had even threatened to kill Thomas, whom he suspected of trying to have an affair with his wife. Furthermore, Thomas’ neighbors were woken by gunshots on the night of the murder. One of them claimed to have seen a car’s headlights in Thomas’ driveway. It’s unlikely a poor black teenager had access to a car. For one, Francis couldn’t even drive.

And to add further doubt, the coroner noted that Thomas was most likely killed by a professional, someone experienced with a gun.

The Retrial

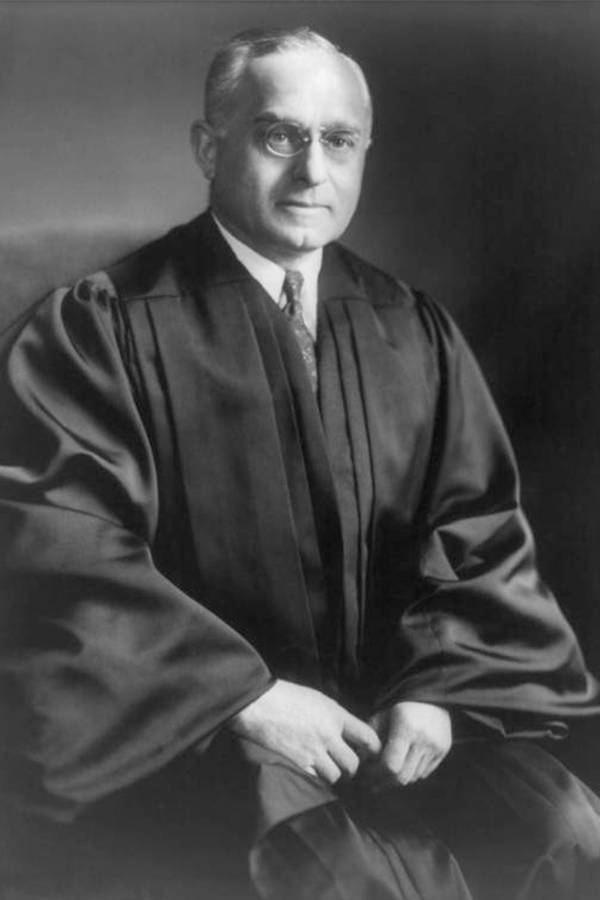

Wikimedia CommonsAssociate Justice Felix Frankfurter of the United States Supreme Court, who attempted to get Louisiana Governor Jimmie Davis to grant Willie Francis clemency.

With such a miscarriage of justice, Francis’ bungled execution just over a year later seemed heaven-sent to his father, Frederick Francis. He managed to hire the services of the lawyer Bertrand DeBlanc, who despite being best friends with the slain pharmacist, agreed to fight for Francis in court. DeBlanc would prove a stark contrast to Francis’ earlier legal representation. Over the next year, he would appeal Francis’ death sentence.

DeBlanc claimed “[i]t’s not human [to make a man] go to the chair twice,” which constituted a “cruel and unusual punishment” under the Eighth Amendment, and also went against the Fifth Amendment clause against double jeopardy, which is punishment for the same criminal act more than once.

DeBlanc had a difficult battle ahead of him. First, he faced the Louisiana Pardons Board on May 31, 1946. Despite DeBlanc’s passionate arguments, Francis was scheduled for another execution on June 7, 1946. So, DeBlanc (with the help of J. Skelly Wright, then a maritime lawyer in Washington) took Francis’ case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Unfortunately, after a shifting of positions between the nine justices, they finally ruled against Francis 5-4. It was one day after Willie Francis’ eighteenth birthday.

Despite his personal ruling against Francis, Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter was conflicted. With the help of a lawyer friend, he sought to persuade the Louisiana Governor Jimmie Davis to grant Francis clemency. Unfortunately, he failed.

DeBlanc never gave up on Francis. He vowed to get him a proper trial after he learned that one of Francis’ original executioners had been drunk when setting up “Gruesome Gertie.” But Francis was denied a new trial. When DeBlanc informed Francis he would take this to the Supreme Court again, Francis told him not to bother. He didn’t want to suffer any more disappointments and said, “I’m ready to die.”

On May 9, 1947, a little over a year after the first execution attempt, Willie Francis was strapped into the electric chair. He was asked if he had any final words. He replied, “Nothing at all.” At 12:05 pm, the switch was pulled and five minutes later Francis was pronounced dead.

Next, read about Hans Schmidt, the only Catholic priest executed in history. Then, read about some of the worst execution methods of all time.