How the Angels of Mons legend had the British public believing that actual divine warriors were on their side against the Germans during The Great War.

City of MonsDetail from “The Angels of Mons” by Marcel Gillis.

In 2001, the British newspaper The Sunday Times reported that Marlon Brando had purchased an antique film reel for £350,000 GBP. Intended to be the basis for Brando’s next movie, the footage had supposedly been found at a Gloucestershire junk shop along with other items and ephemera belonging to World War I veteran William Doidge. While fighting in the Battle of Mons on the Western Front, Doidge was said to have seen something that defied all rational explanation and caused him to dedicate his life to finding the proof of his experiences there. More than 30 years later, in 1952, Doidge did just that and captured footage of a real-life angel on camera.

Or at least that was the story circulating before the whole narrative came crashing down. Within a year, the BBC revealed that there was no evidence of William Doidge’s existence, any film reel, or a planned Marlon Brando project. But why exactly had the British public been so quick to believe, or want to believe, that angels not only existed but could be caught on film?

The answer lies in the strange story of the Angels of Mons, actual angels that were said to have protected British forces during World War I’s Battle of Mons. For more than a century, the tale of the Angels of Mons has proven to be such an almost impossibly resilient legend that the BBC deemed it “the first ever Urban Myth.”

Britain’s First Battle Of The First World War

On June 28, 1914, 19-year-old Bosnian-Serb nationalist Gavrilo Princip killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

After Austria-Hungary then attacked Serbia, Russia (an ally of the Serbs) declared war on Austria-Hungary. In turn, Germany (loyal to Austria-Hungry) declared war on Russia. France mobilized its own forces to assist the Russian Empire and, in doing so, found itself at war with Germany and Austria-Hungary as well.

By the beginning of August, virtually all of Europe had erupted into a war zone as the system of national alliances intended to preserve peace between these competing powers instead sparked a chain reaction of increasing conflict.

On August 2, Germany demanded free passage through Belgium in order to more quickly attack France. When the Belgians refused, the Germans invaded. The United Kingdom had, thus far, stayed out of the conflict, but the sanctity of Belgian sovereignty and neutrality proved to be its breaking point. The United Kingdom declared war on Germany on August 4, Austria-Hungary on August 12, and deployed the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) of about 80,000-130,000 troops to the continent.

The scale of the quickly growing conflict was enormous, but still, many thought the hostilities would end in short order. As one popular phrase put it, many thought the war would “be over by Christmas.”

Wikimedia CommonsBritain’s Royal Fusiliers just before the Battle of Mons. Many of them would not make it back alive.

The harsh reality of modern warfare, however, only became apparent to the British when they arrived at the Belgian city of Mons.

Originally, the BEF and their French allies under General Charles Lanrezac had hoped to coordinate and use the area’s bottleneck of waterways to cut off the German army. Instead, the French accidentally engaged the Germans alone and ahead of schedule, suffering heavy casualties and necessitating a retreat so hasty that the British command did not know it had happened until they were already in position. Outnumbered two to one, the BEF had no choice but to hold the line until the French regrouped.

The fighting began on the morning of August 23 as the first German soldiers began running over the bridges above Mons’ central canal. British machine gunners mowed down one line of men after another as they tried to cross, but in the face of both heavy bombardment and the sheer size of the German army, Britain’s strategy soon proved untenable.

By nightfall, overrun and already having lost more than 1,500 men, the British abandoned the city. The BEF fled their German pursuers for two straight days and nights without food or sleep before they were able to reunite with the French.

There was no time for rest. On August 26, the armies clashed again at the Battle of Le Cateau. The Allied forces were finally able to stop the German advance, but the stalemate came at a high cost: 12,000 BEF troops — at least a tenth of their total forces — had been killed or wounded in the first nine days of combat.

When news from the front filtered back to the United Kingdom, the most common reactions were horror and disbelief. In their first outing, British causalities were higher than half those in the Crimean War, a conflict that had lasted two years. The scale of death and destruction was already inconceivable, and the war was only just beginning. The public began to panic.

Apocalypse Now?

Among a segment of the British population — particularly the religiously-minded — there was no mistaking what this new “War to End All Wars” actually was: the Apocalypse.

In 1918, British General Edmund Allenby actually named a clash against the Ottomans in Palestine “The Battle of Megiddo” to directly invoke the climactic battle of the book of Revelation. Prior to that, in the spring of 1915, pamphlets with titles like The Great War—In the Divine Light of Prophecy: Is it Armageddon? and Is it Armageddon? Or Britain in Prophecy? were already circulating around the country. Even earlier, in September of 1914, Reverend Henry Charles Beeching of Norwich Cathedral told his congregation, “The battle is not only ours, it is God’s, it is indeed Armageddon. Ranged against us are the Dragon and the False Prophet.”

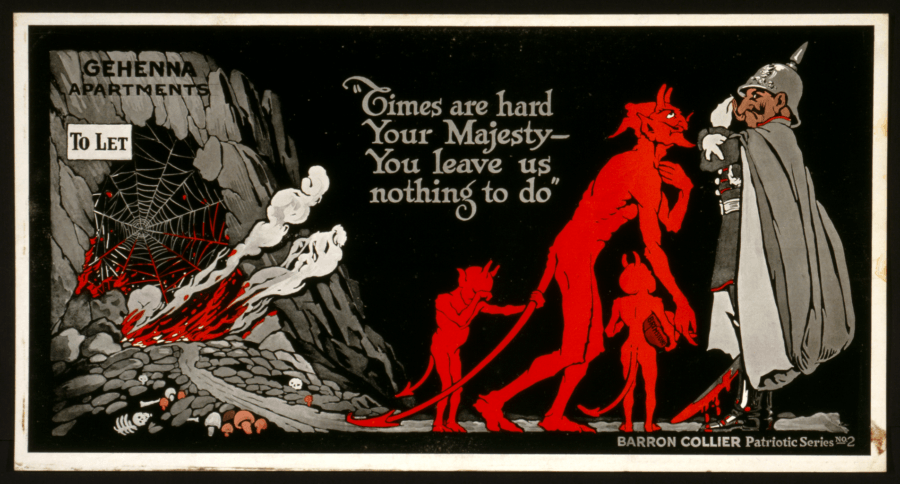

Public DomainA World War I anti-German propaganda cartoon portraying Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm as being in league with demonic forces.

It was against this backdrop that, in the late summer of 1914, a 51-year-old Welsh writer named Arthur Machen sat in another church unable to focus on the priest’s sermon. Distracted by the disturbing reports from the front, he began to imagine a comforting short story — a newly killed soldier’s ascent into heaven.

After mass, he began to write this story — later published as “The Soldiers’ Rest” — but decided he was not capturing the idea correctly. He then tried his hand at another, simpler, story. He finished it in a single sitting that afternoon, titling it “The Bowmen.”

First published in the London Evening News on September 29, 1914, “The Bowmen” focuses on an unnamed British soldier, pinned down in a trench alongside his comrades under heavy German machine gunfire. Fearing that all is lost, the protagonist recalls a “queer vegetarian restaurant” he had once been to in London, one which bears a picture of Saint George and the Latin motto “Adsit Anglis Sanctus Georgius” (“May St. George be a present help to the English”) on all its plates. Steadying himself, the soldier recites the prayer quietly before rising to fire on the enemy.

Suddenly, although no one else seems able to see it, he is startled by an otherworldly apparition.

Voices then cry out in French and English, calling men to arms and praising Saint George as a massive force of ghostly archers appears above and behind the British line, firing ceaselessly into the German forces. The other British soldiers wonder how they’ve suddenly become so much deadlier as the enemy scatters and falls.

No one knows what happened — even the Germans, inspecting dead soldiers without a scratch on them, suspecting it must have been a new chemical weapon. Only the main character knows the truth: God and Saint George had intervened to save the British army.

Machen himself did not think much of his story. It was quaint, far from his best work, but acceptable. Twenty years out from the success of his novella The Great God Pan, tired by career failures, the death of his first wife, and the demands of his reluctant reporting job for the London Evening News, Machen was ok with submitting something that was merely acceptable and so he handed the piece to his editor.

The story came and went with the day’s paper with little fanfare. Machen expected that to be that. It was not.

The Angels Of Mons: Machen’s Own Frankenstein’s Monster

Wikimedia CommonsArthur Machen

In hindsight, “The Bowmen” might be Machen’s most successful story not because of its popularity, but because no one wanted to believe he had made it up. As he put it in his column, “NO ESCAPE FROM THE BOWMEN,” in July 1915, “Frankenstein made a monster to his sorrow… I have begun to sympathize with him.”

The first sign that the story had struck a nerve came the week it was published. Ralph Shirley, the editor of The Occult Review and supporter of a theory that Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany was the Antichrist, reached out to Machen to ask if “The Bowmen” had been based on fact. Machen said it was not. Perhaps surprisingly, Shirley took him at his word.

Later, the editor of the spiritualist magazine Light, David Gow, asked Machen the same question, receiving the same answer. Reporting their conversation in his own column in October 1914, Gow referred to “The Bowmen” as “a little fantasy,” adding, “the spiritual hosts are probably better employed in ministering… to the wounded and dying.”

The trouble started that November with Father Edward Russell, the Deacon of St. Alban the Martyr Church in Holborn. Unlike Shirley and Gow, Russell wrote to Machen and asked permission to republish “The Bowmen” in his parish magazine.

Seeing no harm in this and happy for further royalties, the author agreed. In February of 1915, Russell wrote again, reporting that the issue had sold so well that he wanted to republish it again in the next volume with additional notes and asked Machen to kindly tell him who his sources had been.

Machen explained, once again, that the story was fictional. But the priest disagreed and was sure that the Angels of Mons were real.

As Machen described in his forward to The Bowmen and Other Legends of the War, Russell said “that I must be mistaken, that the main ‘facts’ of ‘The Bowmen’ must be true, that my share in the matter must surely have been confined to the elaboration and decoration of a veridical history.”

Machen quickly realized that nothing he could say would change Russell’s opinion. What was worse, though, was that this man had an audience of willing believers and that there were countless other clergy and congregations like them.

Angelmania

By the spring and summer of 1915, the United Kingdom was in the throes of veritable “Angelmania.” Anonymous reports appeared in newspapers around the country purportedly providing testimony from soldiers who had seen “angels” on the battlefield at Mons.

While all reports spoke of something supernatural that had saved the British soldiers, the descriptions varied by author and publication. Some said they had seen Joan of Arc or Saint Michael leading the British and French soldiers. Some said there were innumerable angels, others said only three, who had appeared in the night sky. Others still said they had only seen a peculiar yellow cloud or fog.

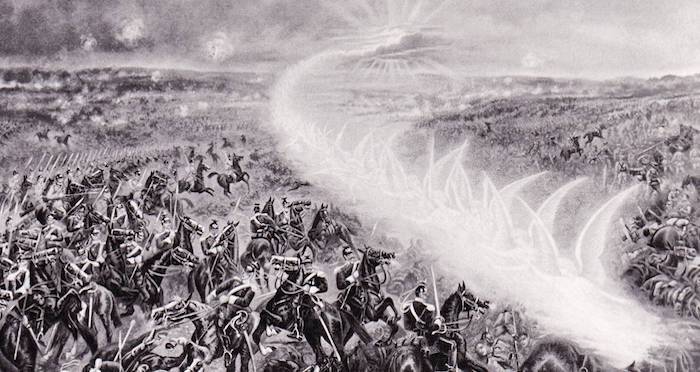

City of MonsDetail from “The Battle of Mons” by an unknown artist.

The explanations for these supposed sightings were equally diverse. To rational critics, the stories were either lies or dismissed as a stress reaction, a collective hallucination born from suggestion and a lack of sleep or perhaps spurred by exposure to chemical weapons.

Spiritualists, meanwhile, suspected that the phantom army could be made up of deceased soldiers killed in the heat of battle and then rising up to assist their still-living comrades. The more traditionally religiously-minded decided it was a modern miracle — Britain’s own answer to France’s “Miracle on the Marne” from September 1914 in which nationwide prayers to the Virgin Mary had supposedly saved the French army, and the Russian reports of the Virgin Mary’s appearing and prophesying Russian victory at the Battle of Augustov that October.

To Machen, however, there was only one explanation: His story had gone viral, mutating and picking up embellishments as it spread from person to person. He did his best to point this out to the public, writing articles and columns to set the record straight.

He showed how no reports published before “The Bowmen” had said anything about the Angels of Mons. And when some of the “true” stories about the Angels of Mons started surfacing, many of the earliest ones even used some of the original details from “The Bowmen”: the vegetarian restaurant, the prayer to Saint George, the German bafflement about what was occurring.

Nevertheless, the public ate up these reports and Angelmania was in full swing.

Angelic Arguments And Apologies

Although initially confident that reason would prevail over public hysteria, Machen’s efforts were mostly met with hostility. At best, his opponents said, he was unsympathetic to the comfort that such stories gave to suffering families. At worst, he was both unpatriotic and unchristian, denying an act of God to boost his own fame and keep himself in the headlines.

Among the most vocal of his critics was Harold Begbie, a journalist, writer, and Christian apologist whose 1915 book On the Side of the Angels went through three sold-out editions. Although in part a catalog of various testimonies and theories, ultimately, Begbie’s somewhat jumbled treatise was less concerned with defining what soldiers had seen than “proving” that Machen had not made up the Angels of Mons.

In addition to citing several anonymous reports that he claimed predated the publication of “The Bowmen” and even saying he’d met with several unnamed soldiers, Begbie went a step further. He suggested that even if Machen had written “The Bowmen” before the Angels of Mons stories became widespread, that did not prove anything. Using the author’s story of his inspiration — that the idea occurred to him as an imagined vision — against him, Begbie proposed that Machen had psychically experienced actual events occurring on the battlefield (“No man of science who has examined the phenomena of telepathy would dispute [it]”). Essentially, according to Begbie, it was the angels who had inspired “The Bowmen,” not the other way around.

Adding insult to injury, Begbie accused Machen of “sacrilege” saying, “Mr. Machen in his quieter and less popular moments will feel a very sincere regret and perhaps sharp contrition” for his attempts to deprive good people of their hope.

Another angel proponent was Phyllis Campbell, a British Red Cross volunteer in France, whose essay “The Angelic Leaders” first appeared in the summer 1915 issue of The Occult Review. Although Campbell did not claim to have seen the Angels of Mons herself, she said that she had nursed several French and English soldiers who had told her strange stories about the retreat from Mons.

According to “The Angelic Leaders,” Campbell first heard about the incident when a French nurse called her over to help her understand an English soldier’s request. Apparently, he was pleading to be given some sort of religious picture. After meeting the man who explained that he wanted a picture of Saint George, Campbell asked if he was Catholic. He responded that he was a Methodist but that he believed in the saints now because he’d just seen Saint George in person.

The Angels Of Mons: From Fiction Into “Fact”

For his part, Arthur Machen had one response to such stories, nearly all of which appeared to be anonymous second- or thirdhand accounts. As he wrote in the conclusion to The Bowmen and Other Legends of the War, “you mustn’t tell us what the soldier said; it’s not evidence.”

Machen was not alone in his assessment. The Society for Psychical Research, a still-extant London-based nonprofit dedicated to the study of the paranormal since 1882, felt compelled to address the Angels of Mons rumors for the readers of its 1915-1916 journal.

After attempting to track down the sources of the reports and letters appearing in British newspapers, the SPR found that in every case the trail ended with someone who had only heard the story second- or thirdhand. Their report thus concluded, “our enquiry [into the Apparitions] is negative… all our efforts to obtain the detailed evidence upon which an enquiry of this kind must be based have proved unavailing.”

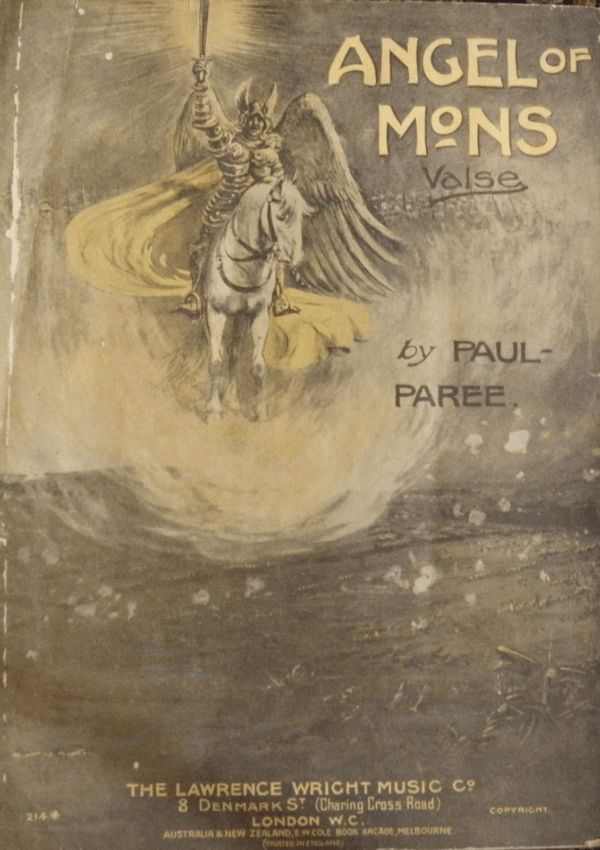

Getty ImagesThe score for Paul Paree’s Angels of Mons waltz.

Nevertheless, the story of the Angels of Mons stuck. By the end of 1916, there was already an Angels of Mons piano solo by Sydney C. Baldock; an Angels of Mons waltz by composer Paul Paree; and a (now lost) Angels of Mons silent film by director Fred Paul. The Angels began to feature in postcards both directly — such as in drawings where they hover behind marksmen mid-shot — and indirectly, as in a series of idealized drawings of attractive nurses dubbed “The Real Angels of Mons.”

The story also began to find its way into propaganda both inside the United Kingdom and on the continent. Soon, angels were a frequent feature in advertisements for war bonds, donations for the Red Cross, and recruitment posters across the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, and the United States.

National Library of Medicine“The Real Angel of Mons” postcard. Circa 1915.

For his part, Machen blamed the angels’ spread on modern churches. If priests spent less time preaching “twopenny morality” instead of Christianity’s “eternal mysteries,” he wrote, believers might have been more scrupulous. But, “separate a man from good drink [and] he will swallow methylated spirit with joy.”

Some blamed Machen’s writing for being too believable in its imitation of journalism or blamed the London Evening News for not adequately labeling the story as fiction. Others, however, have seen something more calculated and perhaps even sinister in the spread of the angel stories.

Tall Tales From The Front

The single definitive description of the Angelic apparitions said to predate the publication of “The Bowmen” is a postcard written by British Brigadier General John Charteris. Dated September 5, 1914, more than three weeks before Machen’s story was published, the text briefly mentions rumors of strange happenings at Mons.

While for some believers this is the long sought-after proof of the angels’ existence, it’s worth remaining skeptical of Charteris’ account. The postcard itself has never been produced for scrutiny, only described in Charteris’ 1931 memoir At GHQ and Charteris’ line of work during World War I gives ample reason to question his motives.

Although not technically affiliated with the newly-formed War Propaganda Bureau, founded on September 2, 1914, Charteris served as the Chief of Intelligence for the BEF from 1916 to 1918. After the war, in a 1925 speech given at The National Arts Club near New York’s Gramercy Park, The New York Times reported of Charteris bragging to his audience about the various false stories he helped invent during the war. The most notable of these were the rumors of “German Corpse Factories” purportedly used by the enemy to turn their own dead soldiers into weapons grease and other essentials.

Although Charteris himself later denied the account in the Times and modern scholars are skeptical that any one person could have started the (false) speculations, it’s worth noting that a number of other false stories from the front pervaded during this period.

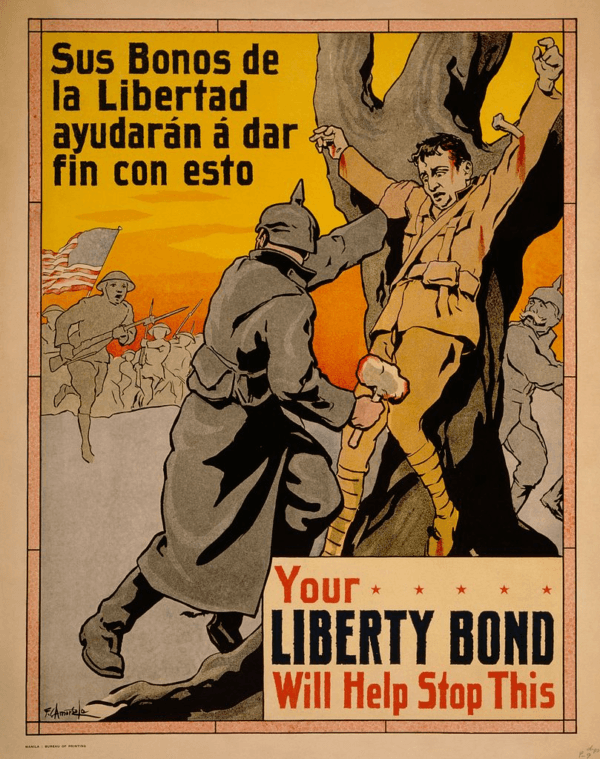

Wikimedia CommonsAmerican Liberty Bond ad featuring the “Crucified Soldier.”

The summer and fall of 1914 was the peak of the so-called “Rape of Belgium,” the term adopted by the British press to describe the atrocious though arguably embellished conduct of the invading German forces. In addition to the molestation of women, the bayonetting of young children and babies (referenced in writings by both Phyllis Campbell and Arthur Machen), there were other more outlandish stories of this time that have never quite held up to scrutiny.

For instance, the legendary “Crucified Soldier” — immortalized in sculptures and illustrations across the United Kingdom and Canada — was supposedly a British or Canadian infantryman who was pinned to either a tree or a barn door either by German trench knives or by bayonets. Despite the contemporaneous ubiquity of the story, no firm evidence has emerged that the event ever occurred. Although no documentation has been found directly linking these stories to the British government, there is no denying that they were convenient for maintaining morale at home and confusing the enemy abroad.

Exactly two weeks before the publication of “The Bowmen,” Arthur Machen described a very different phantom army as “one of the most remarkable delusions that the world has ever harbored.” He was talking about the reports, all second- or thirdhand, of trains carrying Russian soldiers that had apparently been sighted from northern Scotland down to the southern coast.

Although, as Machen pointed out, there would have been no logical reason for Russian troops to be in the British Isles on their way to the Eastern Front, there would have been an incentive to keep such stories in the news. As David Clarke, writer of the 2004 book The Angels of Mons points out, the reports of unexpected Russian troop movements confused embedded enemy spies so much that the German command changed their plans in anticipation of a potential invasion from the North Sea.

The Angels Of Mons Into Eternity

Public DomainBritish War Bond ad featuring angel motif.

In an era characterized by fervent public anxiety for news from the front and intense government censorship about what could be safely printed in British newspapers, it is striking just how many such stories of fantastical happenings on and around the battlefield were able to propagate.

Machen had his own suspicions. He always felt that Harold Begbie, for one, did not believe “a word of it” and had been put up to creating what he wrote as a “publisher’s commission.” Some have gone so far as to suggest that Begbie, already writing poems encouraging young men to enlist, was recruited by Charteris himself for the project.

Although the underlying message of the Angels of Mons stories — that God was on the side of the British in what was a battle of Good and Evil — was certainly beneficial to the war effort, there is no definitive indication of anyone within the British government directing their spread. Still, whether the angels were guided by intelligence services or the pressures of the reading public, the results were the same.

As Edward Bernays, the father of modern public relations and himself an American psychological warfare agent in World War I, noted in his 1923 book, Crystallizing Public Opinion, “When real news breaks, semi-news must go. When real news is scarce, semi-news returns to the front page.”

For better or worse, over the course of the last century, the Angels of Mons have taken flight from short story to semi-news to a legend that has never quite left the public imagination.

After this look at the Angels of Mons, read up on World War I’s Battle of the Somme and Battle of Verdun.