Cabrini-Green was an example of what a public housing project could be, but became so neglected that it was used as the setting for the horror movie Candyman.

It wasn’t supposed to end like this.

As the wrecking ball dropped into the upper floors of 1230 North Burling Street, the dream of affordable, comfortable housing for Chicago’s working-class African Americans came crashing down.

Opened between 1942 and 1958, the Frances Cabrini Rowhouses and William Green Homes started as a model effort to replace slums run by exploitative landlords with affordable, safe, and comfortable public housing.

Ralf-Finn Hestoft / Getty ImagesOne of the “reds,” a mid-sized building at Cabrini-Green.

But although homes in the multistory apartment blocks were cherished by the families that lived there, years of neglect fueled by racism and negative press coverage turned them into an unfair symbol of blight and failure. Cabrini-Green became a name used to stoke fears and argue against public housing.

Nevertheless, residents never gave up on their homes, the last of them leaving only as the final tower fell.

This is the story of Cabrini-Green, Chicago’s failed dream of fair housing for all.

The Beginning Of Public Housing In Chicago

Library of Congress“The kitchenette is our prison, our death sentence without a trial, the new form of mob violence that assaults not only the lone individual, but all of us in its ceaseless attacks.” – Richard Wright

In 1900, 90 percent of Black Americans still lived in the South. There, they struggled under a system of Jim Crow laws designed to make their lives as miserable as possible. Black men were gradually stripped of the right to vote or serve as jurors. Black families were often forced to subsist as tenant farmers. The chances of being able to rely on law enforcement were often nil.

An opportunity for a better life arose with the United States’ entry into World War I. Black Americans streamed into Northern and Midwestern cities to take up vacant jobs. One of the most popular destinations was Chicago.

The homes they found there were nightmarish. Ramshackle wood-and-brick tenements had been hastily thrown up as emergency housing after the Great Chicago Fire in 1871 and subdivided into tiny one-room apartments called “kitchenettes.” Here, whole families shared one or two electrical outlets, indoor toilets malfunctioned, and running water was rare. Fires were frighteningly common.

It was thus a relief when the Chicago Housing Authority finally began providing public housing in 1937 in the depths of the Great Depression. The Frances Cabrini rowhouses, named for a local Italian nun, opened in 1942.

Next were the Extension homes, the iconic multi-story towers nicknamed the “Reds” and the “Whites,” due to the colors of their facades. Finally, the William Green Homes completed the complex.

Chicago’s iconic high-rise homes were ready to receive tenants, and with the closure of factories after World War II, plenty of tenants were ready to move in.

‘Good Times’ At Cabrini-Green

Library of CongressLooking northeast, Cabrini-Green can be seen here in 1999.

Dolores Wilson was a Chicago native, mother, activist, and organizer who’d lived for years in kitchenettes. She was thrilled when, after filling out piles of paperwork, she and her husband Hubert and their five children became one of the first families granted an apartment in Cabrini-Green.

“I loved the apartment,” Dolores said of the home they occupied there. “It was nineteen floors of friendly, caring neighbors. Everyone watched out for each other.”

A neighbor remarked “It’s heaven here. We used to live in a three-room basement with four kids. It was dark, damp, and cold.”

The Reds, Whites, rowhouses, and William Green Homes were a world apart from the matchstick shacks of the kitchenettes. These buildings were constructed of sturdy, fire-proof brick and featured heating, running water, and indoor sanitation.

They were equipped with elevators so residents didn’t have to climb multiple flights of stairs to reach their doors. Best of all, they were rented at fixed rates according to income, and there were generous benefits for those who struggled to make ends meet.

Michael Ochs Archives / Getty ImagesFamilies in Chicago’s Cabrini-Green in 1966.

As the projects expanded, the resident population flourished. Jobs were plentiful in the food industry, shipping, manufacturing, and the municipal sector. Many residents felt safe enough to leave their doors unlocked.

But there was something wrong underneath the peaceful surface.

How Racism Undermined The Cabrini-Green Projects

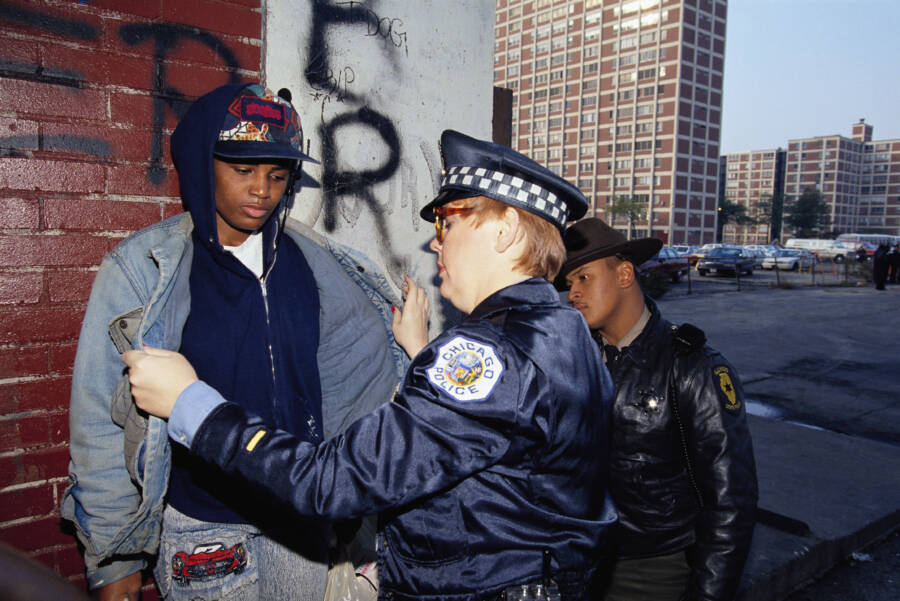

Ralf-Finn Hestoft / Getty ImagesA policewoman searches the jacket of a teenage African American boy for drugs and weapons in the graffiti-covered Cabrini Green Housing Project.

As welcome as the homes were, there were forces at work that limited opportunities for African Americans. Many Black veterans of World War II were denied mortgage loans white veterans enjoyed, so they were unable to move to nearby suburbs.

Even if they managed to get loans, racial covenants — informal agreements among white homeowners not to sell to black buyers — barred many African Americans from homeownership.

Even worse was the practice of redlining. Neighborhoods, especially African American ones, were barred from investments and public services.

This meant that Black Chicagoans, even those with wealth, would be denied mortgages or loans based on their addresses. Police and firefighters were less likely to respond to emergency calls. Businesses struggled to grow without startup funds.

Library of CongressThousands of Black workers like this riveter moved to Northern and Midwestern cities to work in war industry jobs.

What’s more, there was a crucial flaw in the foundation of the Chicago Housing Authority. Federal law required the projects to be self-funding for their maintenance. But as economic opportunities fluctuated and the city was unable to support the buildings, residents were left without the resources to maintain their homes.

The Federal Housing Authority only made the problem worse. One of their policies was to deny aid to African American homebuyers by claiming that their presence in white neighborhoods would drive down home prices. Their only evidence to support this was a 1939 report which stated that, “racial mixtures tend to have a depressing effect on land values.”

Cabrini-Green Residents Weather The Storm

Ralf-Finn Hestoft / Getty ImagesDespite political turmoil and an increasingly unfair reputation, residents of Cabrini-Green carried on with their daily lives as best they could.

But it wasn’t all bad at Cabrini-Green. Even as the buildings’ finances grew shakier, the community thrived. Kids attended schools, parents continued to find decent work, and the staff did their best to keep up maintenance.

Hubert Wilson, Dolores’ husband, became a building supervisor. The family moved into a larger apartment and he dedicated himself to keeping trash under control and elevators and plumbing in good shape. He even organized a fife-and-drum corps for neighborhood kids, winning several city competitions.

The ’60s and ’70s were a turbulent time for the United States, Chicago included. Cabrini-Green survived the 1968 riots after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s death largely intact.

But an unfortunate consequence of this event was that over a thousand people on the West Side were left without homes. The city simply dumped them in vacancies in the projects without support.

The conditions for a perfect storm had been set. Transplanted West Side gangs clashed with native Near North Side gangs, both of which had been relatively peaceful before.

At first, there was still plenty of work for the other residents. But as the economic pressures of the 1970s set in, jobs dried up, the municipal budget shrank, and hundreds of young people were left with few opportunities.

But gangs offered companionship, protection, and the opportunity to earn money in a blossoming drug trade.

The Tragic End Of A Dream

E. Jason Wambsgans/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service via Getty ImagesAlthough many residents were promised relocation, the demolition of Cabrini-Green took place only after laws requiring a one-for-one replacement of homes were repealed.

Towards the end of the ’70s, Cabrini-Green had gained a national reputation for violence and decay. This was due in part to its location between two of Chicago’s wealthiest neighborhoods, the Gold Coast and Lincoln Park.

These wealthy neighbors only saw violence without seeing the cause, destruction without seeing the community. The projects became a symbol of fear to those who couldn’t, or wouldn’t, understand them.

After 37 shootings in early 1981, Mayor Jane Byrne pulled one of the most infamous publicity stunts in Chicago history. With camera crews and a full police escort, she moved into Cabrini-Green. Many residents were critical, including activist Marion Stamps, who compared Byrne to a colonizer. Byrne only lived in the projects part-time and moved out after just three weeks.

By 1992, Cabrini-Green had been ravaged by the crack epidemic. A report on the shooting of a 7-year old boy that year revealed that half of the residents were under 20, and only 9 percent had access to paying jobs.

Dolores Wilson said of the gangs that if one “came out the building on one side, there are the [Black] Stones shooting at them … come out the other, and there are the Blacks [Black Disciples].”

This is what drew filmmaker Bernard Rose to Cabrini-Green to film the cult horror classic Candyman. Rose met with the NAACP to discuss the possibility of the film, in which the ghost of a murdered Black artist terrorizes his reincarnated white lover, being interpreted as racist or exploitative.

To his credit, Rose portrayed the residents as ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. He and actor Tony Todd attempted to show that generations of abuse and neglect had turned what was meant to be a shining beacon into a warning light.

By the late 1990s, Cabrini-Green’s fate was sealed. The city began to demolish the buildings one by one. Residents were promised relocation to other homes but many were either abandoned or left altogether, fed up with the CHA.

Dolores Wilson, now a widow and a community leader, was one of the last to leave. Given four months to find a new home, she only just managed to find a place in the Dearborn Homes. Even then, she had to leave behind photographs, furniture, and mementos of her 50 years in Cabrini-Green.

But even until the end, she had faith in the homes.

“Only time I’m afraid is when I’m outside of the community,” she said. “In Cabrini, I’m just not afraid.”

After learning the sad story of Cabrini-Green, find out more about how Bikini Atoll was rendered uninhabitable by the United States’ nuclear testing program. Then read about how Lyndon Johnson tried, and failed, to end poverty in America.