Some suspect Cixi killed her dead son's pregnant wife so she wouldn't have to compete for power with a legitimate heir.

Within Beijing’s Forbidden City, beyond the imposing gates and the great halls, lie the buildings that once housed the emperor’s harem, an institution that evokes a time of oppression. But it was out of these quarters that a woman born in obscurity and confined as a concubine came to transform the world’s most populous empire.

History long depicted the Empress Dowager Cixi as a scheming despot who brought her country to ruin. But this scapegoating is not only simplistic, it’s inaccurate, as the flawed but skilled de facto ruler brought China into the modern age.

Wikimedia CommonsCixi in c. 1890, when she was around 55 years old. This photo was taken by court photographer Yu Xunling and colorized by Imperial Court painters.

Cixi: Teenage Concubine

The girl who would one day be called Cixi was born in 1835 to the Yehenara clan. Her father seems to have been a regional administrator, although reliable details about her family and early life are lacking. The Yehenara, like the Qing dynasty rulers, were ethnically Manchu, which afforded them special status above the Han Chinese majority.

At age 16, she stood before the Xianfeng Emperor and was chosen for his harem, assigned to the lowest rank. In the Qing Empire, life as an imperial courtesan carried more prestige than you might imagine. It certainly offered more security than most people had during her lifetime. As concubine, she received the title “Noble Lady Lan.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe Xianfeng Emperor was without a son until Cixi came along as a concubine.

Two years into his reign, the emperor had inherited a country in crisis. The Taiping Rebellion, a civil war on an apocalyptic scale, had begun across China and would ultimately leave at least 20 million dead — twice the death toll of World War I.

Capital Of A Suffering Empire

In 1856, Cixi ensured her influence in the emperor’s court after giving birth to his only son and heir. Soon enough, she was the second highest ranking woman in the palace. Nonetheless, her son would officially belong to her superior, the Empress Zhen.

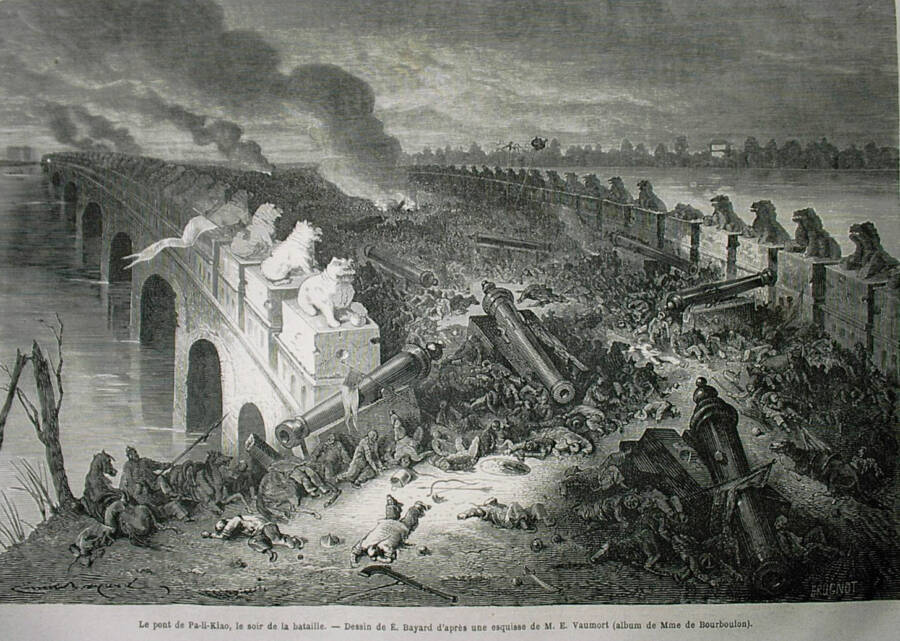

The Xianfeng era was not going well. In addition to the endless civil wars, Great Britain continued to push back against Qing Dynasty isolationism. In 1856, allied with France, the British again went to war with China. In 1858, the imperial court fled from the Anglo-French forces, who took the capital and looted and burned the emperor’s Summer Palaces.

Wikimedia CommonsChina suffered a defeat to the Anglo-French forces in this battle of the Second Opium War, 1860.

The Xianfeng Emperor died in 1861, leaving the empire in a precarious position. In this context, during the royal court’s exile in Rehe province, the newly titled Empress Dowager Cixi, began her consolidation of power.

Filling The Power Vacuum

According to the dying wishes of the Xianfeng Emperor, eight high ministers would form a Grand Council to advise his five-year-old successor, the Tongzhi Emperor. Cixi, meanwhile, had formed an alliance with a higher-ranking colleague, now the Empress Dowager Ci’an. They maintained that they were to be the boy emperor’s official co-regents, with the power to approve or reject any edict.

The empresses dowager went ahead to Beijing ahead of the funeral cortege. They received the cooperation of Prince Gong, one of the late emperor’s brothers and a believer in modernization. Cixi, Ci’an, and Prince Gong staged a coup and led charges of disloyalty by three ministers they deemed to be hostile to their own power base.

Cixi intervened on behalf of the condemned, reducing their sentences from death by slow cutting, to decapitation for one, and suicide by strangulation for the others.

Wikimedia CommonsPrince Gong in 1860, as photographed by Felice Beato.

Three Rulers And A Puppet

The senior Empress Dowager Ci’an would oversee the palace, while Cixi took the lead in affairs of state and politics. Prince Gong was the visible face of the trio, since decorum required that Cixi listen to meetings from out of sight. The young Tongzhi Emperor retreated from public affairs during his upbringing.

Wikimedia CommonsThe young Tongzhi Emperor disliked studies.

The terms of peace after the Second Opium War punished China. Western countries now could establish enclaves along China’s coast. But the Qing court could enlist the help of the French and British in fighting the Taiping rebels. Cixi encouraged the adoption of foreign military technology and guidance.

A new school, the Tongwen Guan, taught international languages and science. Cixi favored many proposals for industrialization and modernization, collectively known as the Self-Strengthening Movement, although she opposed railroads, saying the noise disturbed the dead.

Cixi had developed a close, and perhaps romantic, friendship with An Dehai, one of her eunuch attendants. The favor she showed him did not sit well with Prince Gong and court officials. In 1869, they had the man beheaded.

The Tongzhi Emperor came to rule in his own right at age 17, but had less interest in governing than in sheer entertainment. When he dismissed Prince Gong from his court, he received a stern, protocol-breaking lecture from Cixi and Ci’an, and their ally was reinstated.

Wikimedia CommonsAn Dehai, the Empress Dowager Cixi’s favorite eunuch, was beheaded by Prince Gong and his allies. Cixi apparently did nothing to stop them.

The Tongzhi Emperor died at age 18, and rumors suggested syphilis as the cause, given his multiple affairs with prostitutes. Modern review has ruled that out, but the gossip is a measure of his public image.

Surprising Reversals

Cixi hadn’t gotten along with her son’s wife, the Empress Xiaozheyi, who regarded the former concubine as an inferior. Suspiciously, Xiaozheyi died very soon after her husband, along with her unborn child.

Cixi then adopted her three-year-old nephew, who became the Guangxu Emperor. Oddly, she ordered him to call her his “royal father.” Ci’an emerged as the principal regent of the period, as Cixi was suffering bad health. But in 1881, Ci’an herself died of a stroke. Cixi was again in command.

The Guangxu Emperor assumed power at age 18 in 1889, and Cixi nominally went into retirement on the outskirts of Beijing, though foreign governments sometimes wrote to Cixi directly, bypassing the emperor.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Empress Dowager (center) with courtiers in 1902, the year following the Boxer Rebellion. Empress Xiaodingjing stands second from left. Yu Xunling, photographer.

In 1898, Cixi opposed a rapid modernization program, called the Hundred Days’ Reform. Advocated by the emperor and his advisors, the plan proposed a constitutional monarchy. Cixi worked to block the reforms, and to remove the reformers, executing those who didn’t manage to escape first. The Guangxu Emperor was placed under house arrest on an island adjacent to the Forbidden City, and would never again wield power.

Anti-foreign sentiment in China coalesced into the Boxer Rebellion, named for its organization’s martial arts practices. In another turn, Cixi expressed sympathy with the movement. In 1900, militias attacked the coastal mini-colonies. Following the defeat of the Boxer Rebellion, Cixi publicly apologized for supporting it, and China made restitution payments to the countries affected.

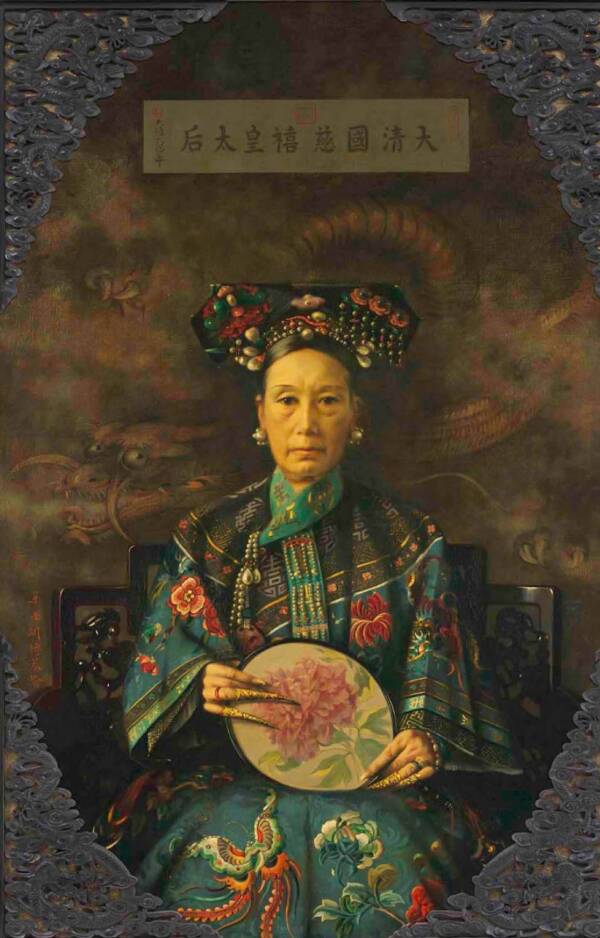

Cixi now changed course again, advocating for a limited monarchy. She stood for photographs and painted portraits in a kind of charm offensive, offering prints to palace visitors.

But as her health failed, Cixi arranged that yet another child would be next in line for the throne, a declaration she made from her deathbed before her death on Nov. 15, 1908. Just the previous day, the Guangxu Emperor had himself died of arsenic poisoning. Cixi was buried in a palatial tomb east of the capital.

Upon hearing the news of the deaths, anarchist Wu Zhihui referred to Cixi and her nephew as a “vermin empress and vermin emperor” whose “lingering stench makes me vomit.”

Wikimedia CommonsThis portrait of the Empress Dowager Cixi was painted in 1905 by Dutch artist Hubert Vos.

Self-Serving Usurper Or Brilliant Leader?

In the Republic of China, Cixi was a target for contempt. Her image in the English-speaking world was colored by the book China Under the Empress Dowager, written by John Otway Percy Bland, a journalist, and Edmund Backhouse, an utter fraud, whose fantastical stories Bland chose not to question.

The early Chinese Communist Party had no love for any “feudal” tyrants. Only in the 1970s did anyone question the melodramatic caricature of Cixi as a “Dragon Lady,” an unfortunate nickname that remains.

Modern historians credit the Empress Dowager Cixi for pulling China through difficult times, while others vilify her for her numerous executions and opposition to crucial reforms that would have risked her own hold on power. It’s remarkable that she held onto power for 45 years — but at what cost?

After learning about the rollercoaster life of the Empress Dowager Cixi, look at these 44 stunning photos of Qing dynasty China. Then, read how the eunuch Zheng He became one of China’s most legendary explorers.