As a child, Evelyn Einstein was told she was actually Albert Einstein's biological daughter. But she died before she could prove it.

Evelyn Einstein always claimed that renowned physicist Albert Einstein was her biological father. But she never had any proof.

As the granddaughter of Albert Einstein, Evelyn Einstein’s life was markedly affected by the psychological baggage and social pressures stemming from her renowned surname.

Evelyn came into the Einstein family not by blood but through adoption. Being the only adopted child of Albert’s eldest son, Hans Albert, conspiracy theories about the true nature of Evelyn’s relationship to the family grew. Evelyn herself said she had been told as a child that she was actually Albert Einstein’s biological daughter.

Evelyn’s close friend and author Michele Zackheim described her as an intelligent and humorous woman — traits some would say were shared by her famous grandfather. But Evelyn also suffered from depression.

“She was physically ill, but I felt that she needed psychological help far more than anything else,” Zackheim wrote about their 15-year friendship.

Toward the end of her life, the granddaughter of Albert Einstein suffered a bout of homelessness, worked multiple odd jobs to survive, and was cut off from the rest of the living Einstein clan.

Growing Up As An Einstein

Wikimedia CommonsMileva Marić and Albert Einstein. Evelyn’s father, Hans Albert, was their eldest son.

Evelyn was born in Chicago in 1941 to a 16-year-old girl named Joan Hire. Hans Albert Einstein, the famous physicist’s second child and eldest son, and his wife, Frieda, adopted baby Evelyn when she was just eight-and-a-half days old.

But Evelyn was not Hans and Frieda’s only child; the married couple had one living biological child, Bernhard Caesar Einstein, born a decade earlier, and two other children who had already died in their infancy.

Several years after Evelyn’s adoption, the family of four moved to Berkeley, California, where Hans Albert became a hydraulic engineering professor.

Hans Albert did not pursue the same field as his renowned father, but he was nonetheless a brilliant scientist in his own right. However, growing up in a family of Einsteins had instilled a deep insecurity within himself. It didn’t help that friends of the family believed that his brother, Eduard, was the one who had inherited his father’s genius.

The Burden Of Genius

Water Resources Center ArchivesHans Albert holding an award for his work.

According to Evelyn, her father was overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy when compared to his brother, who was later diagnosed with schizophrenia and remained in a psychiatric institute in Switzerland until he died.

“He was definitely the genius,” Evelyn said. “Next to Tete [Eduard], my father was just a plodder.”

As for her famous grandfather, Evelyn rarely got to see him. The families lived on different coasts: Evelyn and her family were in California (though Evelyn did some time at a boarding school in Switzerland), and her grandfather Albert lived in Princeton, New Jersey until his death.

As she grew older, Evelyn became an opinionated and outspoken college student, which led her into student activism. In 1960, she got arrested in San Francisco for protesting hearings there of the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Evelyn eventually learned to speak four or five different languages and received a master’s degree in medieval literature from the University of California, Berkeley. But her father’s insecurities as an Einstein heir eventually passed on to her.

It’s Not Easy Being An Einstein

Wikimedia CommonsEvelyn Einstein attended U.C. Berkeley in the 1960’s. Pictured above is Sproul Hall in 1962.

“It’s not so easy being an Einstein,” Evelyn told Michael Paterniti in his 2000 book Driving Mr. Albert: A Trip Across America With Einstein’s Brain. “When I was in school at Berkeley in the ’60s, I could never tell if men wanted to be with me because of me, or my name. To say, you know, ‘I had an Einstein.'”

Evelyn mentioned in interviews that she was repeatedly told by family and friends that she was, in fact, an Einstein by blood.

Gina Zangger, the daughter of Albert Einstein’s close friend Heinrich Zangger, had attended the same Swiss boarding school as Evelyn’s adoptive parents. By Gina’s account, which she divulged to Robert Schulmann of the Einstein Papers Project, Frieda, Evelyn’s mother, told school officials that Evelyn’s adoption was a favor to Albert.

Gina said she found out about the secret after it was shared to her by the boarding school director’s wife, who was also her good friend.

Since that time, Evelyn has harbored suspicion that she was not Albert’s adoptive granddaughter, but his biological and illegitimate daughter from an affair between Albert and a ballet dancer from New York.

Evelyn playfully added: “Even my sister-in-law, Aude, told me I was a blood member of the family. And she didn’t even like me!”

Nobody had proof about her rumored identity. She came close to proving her paternity through a DNA test using a piece of Albert’s brain.

Thomas Harvey, a pathologist who handled the deceased physicist’s brain and stole the brain to study it, had offered Evelyn a piece of Albert’s brain as a gift. Unfortunately, Harvey and Paterniti, who was traveling with him, left without giving it to her.

Discovering Albert Einstein’s Private Life

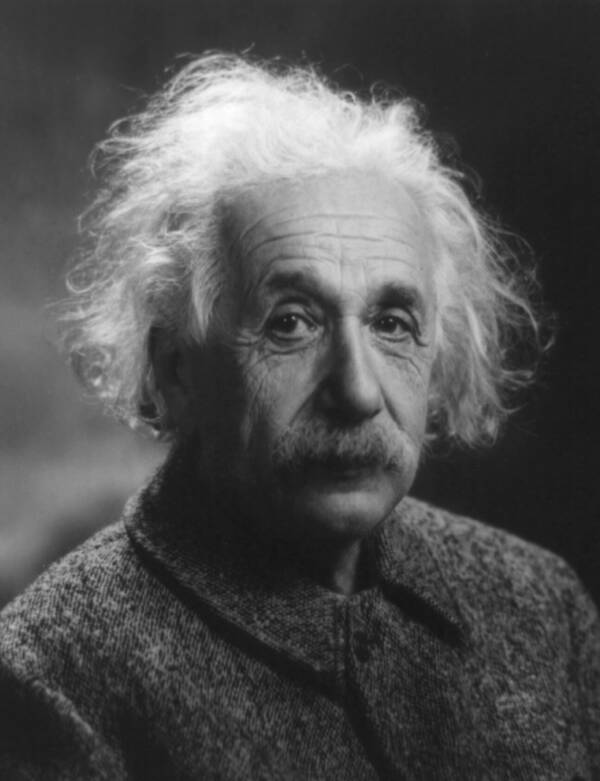

Wikimedia CommonsAlbert Einstein in his old age.

Evelyn also played an instrumental role in a discovery that shed an unprecedented amount of light on Albert Einstein’s private life.

In 1986, Evelyn found an unpublished manuscript by her mother quoting love letters written by the famed physicist. The discovery led to a major finding six years later, when hundreds of never-before-seen letters that Einstein wrote to his first wife, Mileva Marić, and his family members were found in a safe-deposit box in Berkeley.

The letters unveiled an intimate side of the scientist that the public had not known, particularly within the context of his tumultuous relationships with his son and wife. They also exposed the bombshell revelation that Albert and Mileva had had a daughter, Lieserl, before they were married.

About a decade later, Evelyn joined other family members and filed a lawsuit to remove her nephew, Thomas Einstein, the son of Bernhard, from the trust that was responsible for overseeing Albert’s personal letters. They accused Thomas of hiding $15 million worth of letters from the rest of the family. A settlement was ultimately reached in 1996, the terms of which remain undisclosed.

Evelyn Einstein’s Deteriorating Health

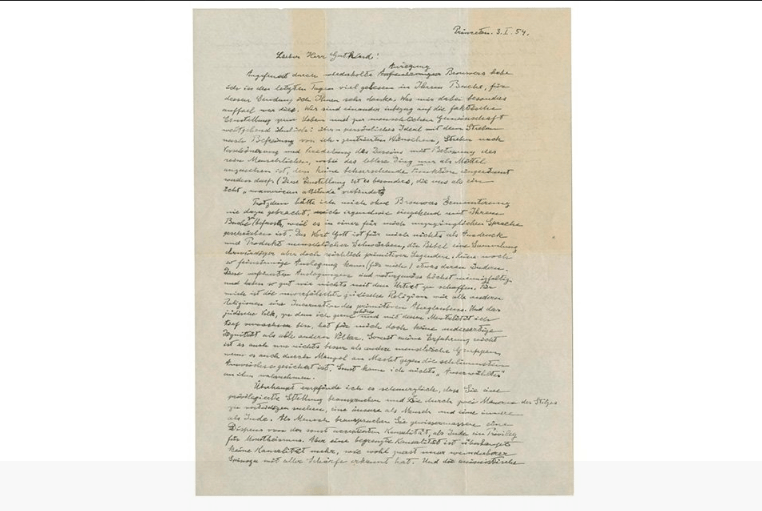

TwitterThis letter by Albert Einstein sold for $2.9 million.

By the time of the lawsuit, Evelyn was wheelchair-bound. Her physique had deteriorated from bouts of breast cancer and liver disease. She said that her grandfather had only left her $5,000. Everything else, including 75,000 papers of his life’s work — his entire literary estate — was left to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

According to a Forbes list of Top-Earning Dead Celebrities, Albert Einstein’s name and likeness draw annual earnings of $10 million — of which Evelyn didn’t get a dime.

Living In Poverty

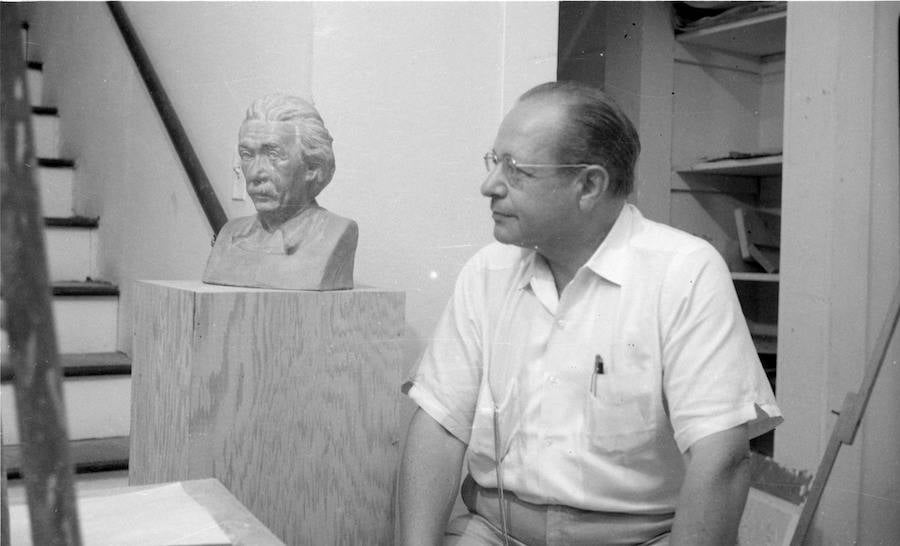

Clemson University Library.Hans Albert Einstein posing with a bust of his father, Albert Einstein.

After an ugly separation from her husband, anthropology professor and Bigfoot theorist Grover Krantz, Evelyn moved in with her father. When he died in 1973, Evelyn was forced to live out of her car, and resorted to dumpster diving.

“I can tell you every good garbage dumpster in the area,” she shared with Zackheim. “But I never panhandled a penny.”

A credit to her perseverance, Evelyn was able to get back on her own two feet and move into a shared home with three other women in Berkeley. She started collecting disability checks and worked multiple odd gigs. Among the kinds of work that she picked up were dogcatcher, police officer, bank teller, boat keeper, and cult deprogrammer.

She also had a collection of miscellaneous items from her family, like a box of her uncle Eduard’s psychiatric drawings of nude women and her mother’s old jewelry that she kept hidden under her mattress.

By the end of Evelyn’s life, she was no longer in contact with the Einstein family. To the end, though, she still had enough fight in her to claim her rights as Albert’s heir. Sometime before her death in 2011, Evelyn began another dispute with the Hebrew University over a portion of Albert Einstein’s estate profits.

Evelyn, who was almost 70 and suffered from multiple illnesses, wanted the money so that she could move into an assisted living facility.

“I’m outraged,” she told CNN in an interview. “It’s hard for me to believe [the university] would treat the family the way they have, which has been abysmally.” Not long after, Evelyn Einstein died in her home in California.

After reading up on Evelyn Einstein, an Einstein heir who died poor and alone, learn about Albert Einstein’s marriage with his first cousin, Elsa. Then, find out the story behind Albert Einstein’s iconic tongue photo.