Under Hideki Tōjō's leadership during WWII, Japan conducted brutal humans experiments, enslaved thousands of "comfort women," and routinely cannibalized POWs. He would pay for these crimes with his life.

The Japanese leader during World War II, Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō is often painted as a warmongering hater of the West bent on world dominion. He was to be prosecuted and executed as a Class-A war criminal with much of the guilt of the conflict laid on him. But the truth was more complex and not completely resolved.

Hideki Tōjō’s Loyalty To The Emperor

Hideki Tōjō was born on December 30, 1884 in the Kōjimachi District of Tokyo. His father was Hidenori Tōjō, a military officer of the samurai caste.

Tōjō came of age well after the Meiji Restoration, which in 1868 ended the Shogunate and restored power to the emperor. The restoration ostensibly ended the samurai class as part of its reform to modernize and industrialize Japan.

But the old divisions between commoners and aristocratic nobility were hard to crack.

Tōjō followed in the footsteps of his father. In 1905, he graduated 10th in his class from the Japanese Military Academy and was inculcated with the military values of the period: complete loyalty to the emperor and a subversion of one’s individuality to the state.

National ArchivesGeneral Hideki Tōjō bowing to Emperor Hirohito. December 1942.

Developing Anti-Western Views

As a young man, Tōjō developed anti-Western beliefs. From 1904 to 1905, Japan waged a successful war against the Russian Empire for control over Manchuria and Korea. Despite being the clear victor in the combat, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt negotiated the Treaty of Portsmouth, which did not cede Manchuria to Japan but rather restored the territory to China.

Some, including Hideki Tōjō, viewed this as an racist affront to Japan, that the West would never recognize a non-white country as a first-tier power.

Tōjō’s view was further solidified when the U.S., under the leadership of President Woodrow Wilson, vetoed a Japanese proposal recognizing the equality of all countries, regardless of race, in the covenant for the League of Nations. Then, in 1924, the U.S. Congress passed a bill banning immigration from all of Asia. (The U.S. had already banned immigration from China with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.)

It seemed to Tōjō that the U.S. would never accept Japan as an equal. When returning home from Germany in the early 1920s, he traveled by train across the U.S. — his first and only time in the country. He was unimpressed.

Wikimedia CommonsMembers of the League of Nations Commission, which rejected Japan’s proposal for racial equality.

The Razor Is Born

In 1931, the Japanese invaded Manchuria and established the puppet state of Manchukuo. In 1934, Hideki Tōjō was promoted to major general and the following year he commanded the Kempetai, Japan’s Gestapo-style military police force, in Manchuria. He expressed views that Japan needed to become a totalitarian state to prepare for the next inevitable war.

As his power grew, he earned the nickname Kamisori, meaning “Razor,” for his decisiveness and strict by-the-book mentality (some sources say it was because of his cold-bloodedness). His next step up was in 1937 to chief of staff of the Kwantung Army. The next year he became Japan’s vice-minister of war, and in 1940 he was appointed army minister.

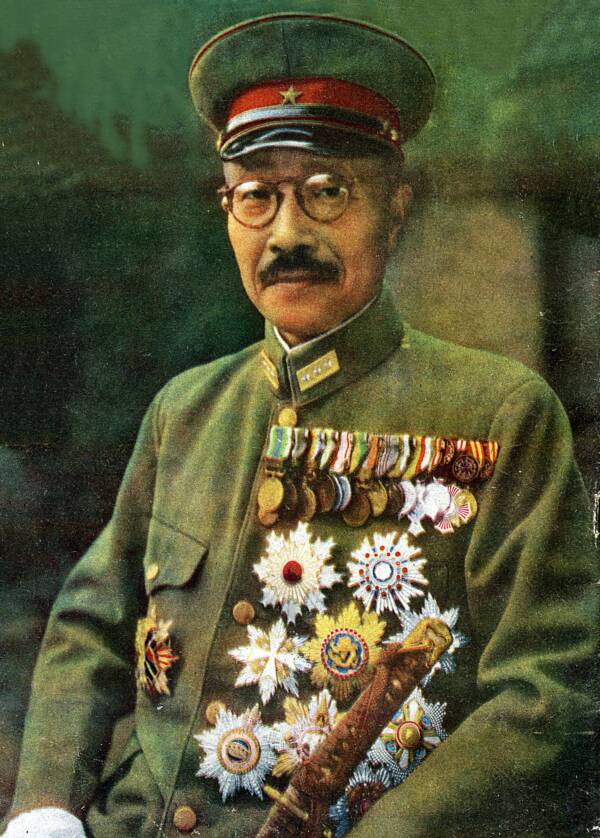

Wikimedia CommonsGeneral Hideki Tōjō in full uniform.

War Begins

It was around this time that relations between China and Japan reached a crisis point. In July 1937, a skirmish at Beijing’s Marco Polo Bridge, called the “China Incident,” began the Second Sino-Japanese War — over Western objections.

Japan captured the Chinese capital of Nanking, and then proceeded to systematically rape and kill its people for six weeks in what is now known as the Rape of Nanking.

The United States imposed economic sanctions and embargoes on Japan, including the restriction of key strategic resources such as scrap metal and gasoline (more than 80 percent of Japan’s petroleum came from the U.S.). Instead of crippling Japan, these sanctions emboldened it to align against the U.S.

Japan signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy in September 1940. It then moved into Southeast Asia to secure strategic resources there; France’s Vichy regime allowed Japan to stage troops in northern Indochina (essentially present-day northern Vietnam), effectively blockading China and preventing it from importing arms and goods via its southern neighbors.

The United States objected with more sanctions, but Japan would come to occupy all of French Indochina in July 1941.

Wikimedia CommonsDead Chinese soldiers who have been killed by the Japanese Army in a ditch.

Hideki Tōjō’s Razor Gets An Edge

Japan was deadlocked as to whether to wage war against the U.S. or to continue what may be fruitless diplomatic negotiations in order to regain its precious gasoline supply.

On the pro-war side was Hideki Tōjō, who feared that negotiating with the U.S. would risk ceding too much of Japan’s territory in Indochina, Korea, and China. “If we yield to America’s demands,” he said in a cabinet meeting, “it will destroy the fruits of the China incident. [Manchuria] will be endangered and our control of Korea undermined.”

On the other side was Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, who desperately wanted peace with the U.S.

Tōjō ended up on top. On Oct. 16, 1941, Konoe resigned as prime minister, recommending to Emperor Hirohito that Prince Naruhiko Higashikuni replace him. But Hirohito chose a different tack: The next day, he appointed Hideki Tōjō, the career general and militaristic hardliner, as prime minister of Japan.

Despite General Tōjō’s militaristic position, he promised the Emperor that he would attempt to reach an accommodation. However, it was also agreed that if no resolution could be reached by December 1, Japan would go to war against the United States.

On November 5, 1941, the attack on Pearl Harbor was approved and the task force to carry out the attack began assembling on November 16.

It is important to note that often Tōjō is credited with singly ordering the attack on the United States. The truth is more complex. While it is true that Tōjō was prime minister, the decision was made by consensus between him, cabinet ministers, and military chiefs.

To Pearl Harbor

The situation grew more precarious. On November 26, 1941, the United States issued a memorandum called the Hull Note, named after Secretary of State Cordell Hull, which demanded the complete withdrawal of Japanese troops from China and French Indochina.

Hideki Tōjō saw this as an ultimatum. There would be no peace. Emperor Hirohito, under the advice of Tōjō and his cabinet, consented to the Pearl Harbor attack on December 1 and carried it out on December 7.

In a memorandum about Hirohito’s assent, Tōjō was quoted as saying, “I’m perfectly relieved. You can say we have already won [the war], given the current situation.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe USS Shaw explodes during Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. Dec. 7, 1941.

“Our Empire, for its existence and self-defense has no other recourse but to appeal to arms and to crush every obstacle in its path,” declared Hirohito following the attack. Japan was officially at war with the United States and the British Empire and was now entering World War II.

Victory And Atrocity

Initially, Tōjō enjoyed great popularity as the Japanese experienced victory after victory. To solidify his power, on April 30, 1942 Tōjō held a special election to fill Japan’s legislature with his pro-war supporters.

Throughout the war, Tōjō was hamstrung by the Japanese bureaucracy and infighting among the armed services. When he tried to concentrate power into his hands, some criticized the move by telling him that Germany’s errors in the war was due to Hitler’s micromanagement. Tōjō reportedly replied, “Führer Hitler was an enlisted man. I am a general.”

Tōjō never got Hitler’s level of authority, but he did commit some comparably horrible crimes.

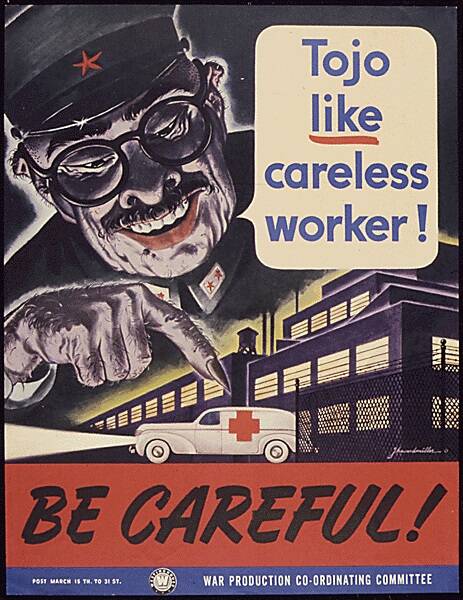

National ArchivesA World War II propaganda poster from the War Production Board.

In Allied propaganda, however, Tōjō was caricatured and vilified as the equivalent of a Hitler or Mussolini. He became the poster boy for all the worst of Japan’s militarism and was widely thought to be the one responsible for Japan’s atrocities and warmongering.

As for the atrocities, there were many. The death rate of Western prisoners in Japanese POW camps was 27 percent — seven times higher than in German POW camps.

In addition, he approved biological experiments on POWs. Tōjō also consented to the forced prostitution of so-called “comfort girls” at the hands of the Japanese military. On the other hand, Tōjō did approve the resettlement of Russian Jewish refugees into Manchuria despite German protestations.

Wikimedia CommonsIn April 1942, the Japanese forcibly moved tens of thousands of American and Filipino prisoners of war to Japanese-controlled areas. Thousands died along the way, and the event — dubbed the Bataan Death March — was later ruled to have been a war crime.

However, after the Battle of Midway in June 1942, the tide turned to the Americans’ favor and Tōjō’s popularity ebbed. As the Americans drove the Japanese out of their conquered territories, confidence in the prime minister slipped even further.

By this point, it became clear to many of those in power in Japan that the war was lost and that Tōjō, because of how he was generally viewed by the West, was in no position to negotiate a peace treaty or ensure the survival of Japan. He resigned on July 18, 1944, after the Japanese defeat at Saipan and two and a half long years of war.

Tōjō’s Failed Suicide

Even out of power, Hideki Tōjō was still a militarist. On Aug. 13, 1945, as Japan’s surrender to the West was imminent, he wrote: “We now have to see our country surrender to the enemy without demonstrating our power up to 120 percent. We are now on a course for a humiliating peace, or rather a humiliating surrender.”

Japan’s unconditional surrender came with an announcement by Emperor Hirohito on Aug. 15, 1945, which was formalized on September 2.

On September 11, Gen. Douglas MacArthur ordered the arrest of Tōjō, who had gone into seclusion. The arrest was carried out by Lieut. John J. Wilpers, Jr.

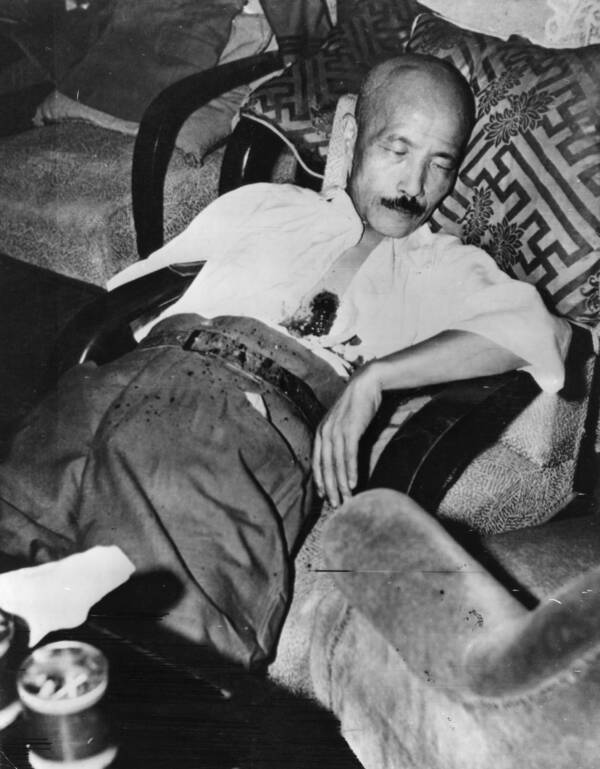

Tōjō was easy enough to find, but rather than submitting to arrest he shot himself in the chest. Japanese reporters recorded Tōjō’s words, “I am very sorry it is taking me so long to die. The Greater East Asia War was justified and righteous. I am very sorry for the nation and all the races of the Greater Asiatic powers. I wait for the righteous judgment of history. I wished to commit suicide but sometimes that fails.”

The wound was severe, but not fatal.

Keystone/Getty ImagesTōjō sprawls in a chair with a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the chest. He had attempted suicide to escape trial as a war criminal.

Trial

Tōjō was nursed back to health and charged as a class-A war criminal.

The indictment maintained that Tōjō and others “contemplated and carried out…murdering, maiming and ill-treating prisoners of war [and] civilian internees…forcing them to labor under inhumane conditions…plundering public and private property, wantonly destroying cities, towns and villages beyond any justification of military necessity; [perpetrating] mass murder, rape, pillage, brigandage, torture and other barbaric cruelties upon the helpless civilian population of the overrun countries.”

In Tōjō’s view, he had one last responsibility for his emperor, and that was to take complete blame for the war.

He wrote in his prison journal, “It is natural that I should bear entire responsibility for the war in general, and, needless to say, I am prepared to do so.”

Tōjō wasn’t called to testify until the end of 1947, after which an international military tribunal found him guilty of waging unprovoked war against China; waging aggressive war against the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands; and authorizing and permitting the inhumane treatment of prisoners of war.

Wikimedia CommonsGeneral Hideki Tojo testifies at his war crimes trial in Tokyo.

Execution And Commemoration

Hideki Tōjō was found guilty and sentenced to death on November 12, 1948 and hanged six weeks later.

His ashes were interred between the Yasukuni Shrine and Zoshigaya Cemetery in Tokyo. This was not without controversy: The Yasukuni Shrine, also known as the War Criminal Shrine, is seen as a symbol of Japan’s militaristic past and even today is a target for vandalism.

There has been much debate over the years as to Tōjō’s culpability for Japan’s World War II atrocities and the role of Emperor Hirohito. Over the last several decades, historians have unearthed evidence that the emperor wasn’t a powerless dupe, but active in Japan’s most important decisions of WWII.

Hirohito was never tried as a war criminal largely because Gen. Douglas MacArthur believed the continuation and approval of the emperor was vital for the development of Japan’s democracy.

At the same time, Tōjō’s descendants have sought to rehabilitate his image. In an 1999 interview with the New York Times, Tōjō’s granddaughter, Yuko Tōjō, said, “People always talk about Hitler and Tōjō in the same breath…but they were utterly different. Hitler murdered the Jews, but Tōjō didn’t kill his own people….Japan was encircled by hostile nations before the war, and it was strangled by sanctions and had no resources….So General Tōjō, for the sake of the survival of his people, had to resort to arms.”

Wikimedia CommonsGen. Douglas MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito. September 1945.

While this amount of historical revisionism may never fully win out over time, it is clear that the story of Hideki Tōjō is more nuanced than common perception.

After learning about the life of Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō, take a look at Japan’s worst war crimes of World War II. Then, learn the bloody history of the Pacific Theatre, the Second World War horror show the world wants to forget.