art

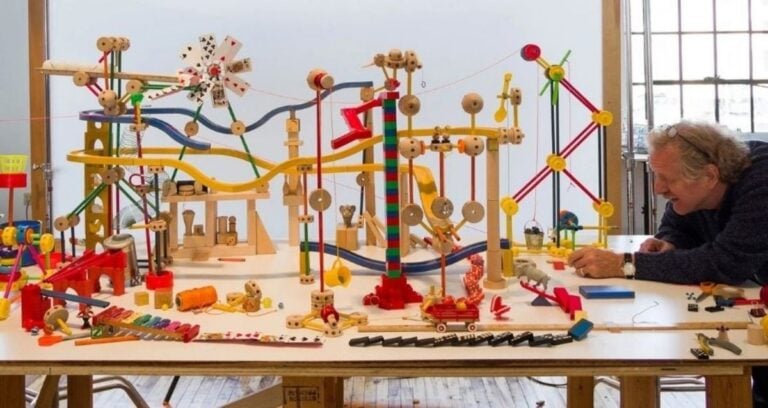

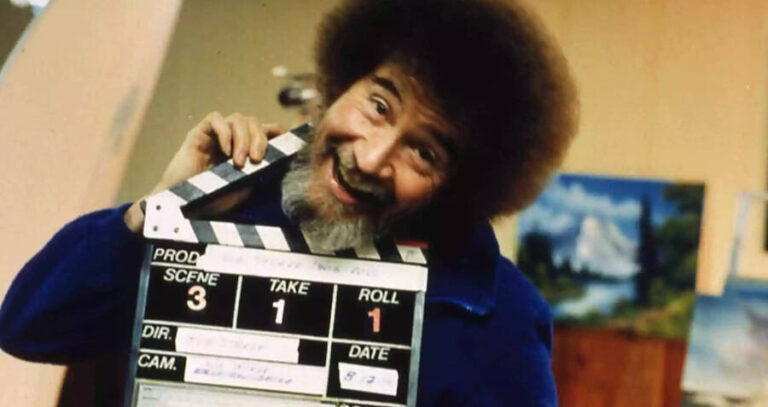

Thousands of years ago, our ancestors scrawled on the walls of caves. Then they slowly began to carve the stone and paint the canvases that occupy the world’s greatest museums to this day. Now, we create things that those ancestors of ours would have never even dreamed possible.

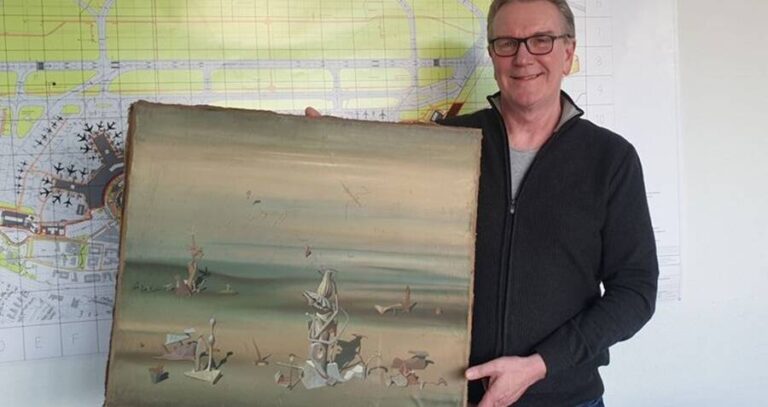

From painting and photography to film and sculpture, from the Classical and the Impressionist to the Abstract and the Surrealist, this is humankind’s most interesting art.