The Underground Railroad was neither underground nor a railroad — but it did fight the system of slavery by secretly shepherding slaves to freedom in the North.

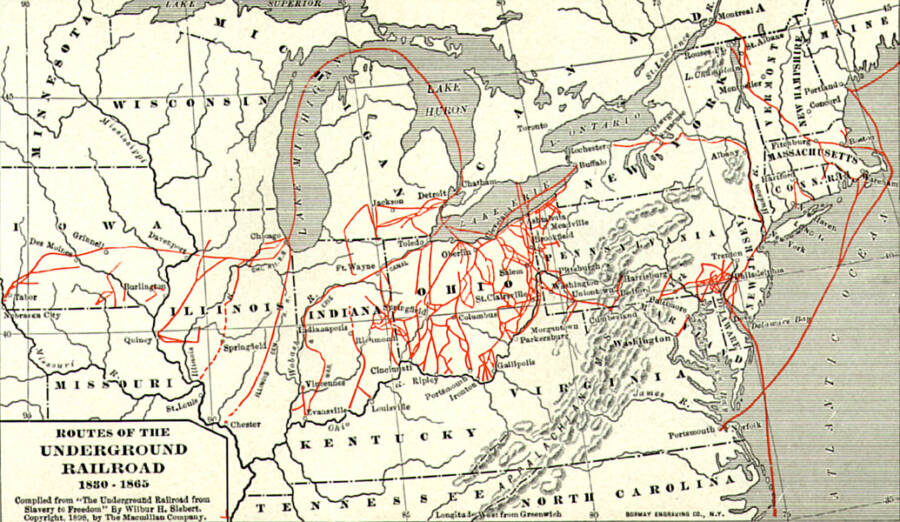

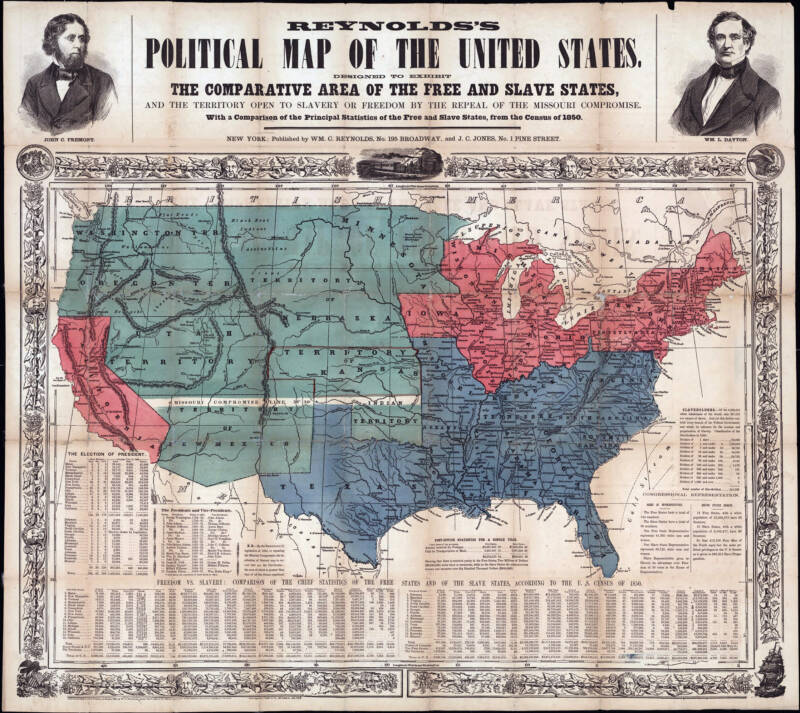

Wikimedia CommonsWilber Siebert’s map of the Underground Railroad. When the U.S. enacted the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, runaway slaves had to travel all the way to Canada in order to truly be free.

On a night in 1831 something stirred along the shores of the Ohio River. A splash, followed by men swearing and a frantic search for a canoe. The specific details are hazy, but the bones of the matter are known: A slave named Tice Davids, in desperate flight from a plantation in Kentucky, leapt into the Ohio River in hopes of reaching freedom on the other side.

He made it. According to legend, the furious plantation owner sneered that Davids had “gone off on an underground railroad.” And thus the term “underground railroad” came into the American vernacular — but the shadow organization that bore its name had been operating for decades.

What Was The Underground Railroad?

Historians contest the idea that the plantation owner coined the term “underground railroad.” However, the Davids anecdote illustrates well the high stakes of escape and the whispered promise of certain safe places. The term quickly spread. In 1845, Frederick Douglass groused that reckless abolitionists had talked it up so much, it had become an “upperground railroad.”

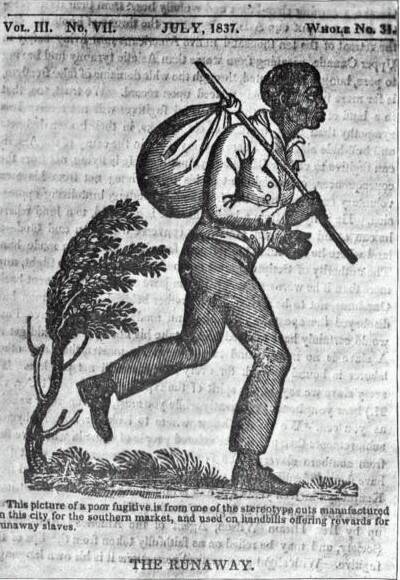

Wikimedia CommonsA common image used in wanted ads for runaway slaves.

Because the Underground Railroad operated in secrecy, it’s difficult to determine exactly when the organization started. But slaves had been running away for centuries.

By the time Davids fled across the Ohio River, 38 years had passed since the first Fugitive Slave Law in 1793 — and indeed, the right of southern slave owners to recapture fugitive slaves is enshrined in the Constitution.

So what was the Underground Railroad? It was not an established institution with an established series of safe-houses. Rather, as historian Eric Foner notes, it was a loose network of incomplete and unorganized local groups with the same goal: to help fugitive slaves to safety and freedom.

Slavery In 19th-Century America

By the time Davids fled across the Ohio River in 1831, 2 million people in the United States were enslaved — more than 15 percent of the country’s population.

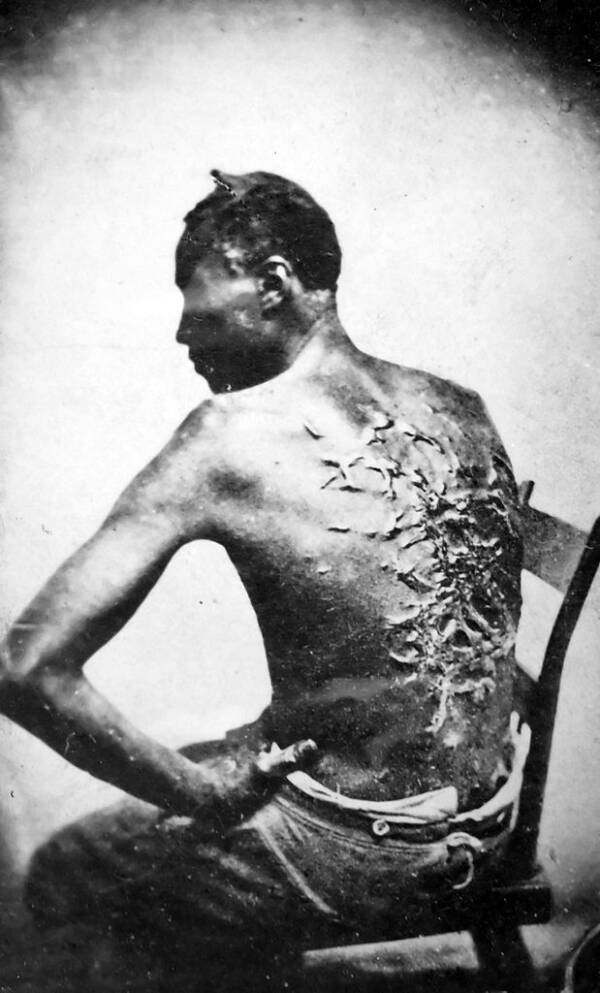

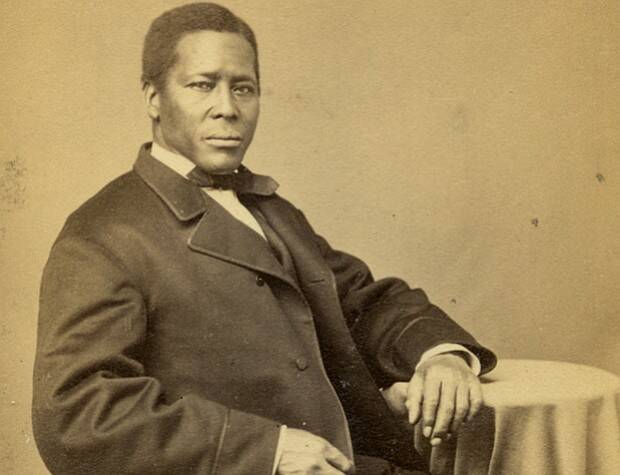

Wikimedia CommonsGordon, seen here in 1863, escaped a Louisiana plantation and found refuge at a Union Army camp near Baton Rouge. Abolitionists distributed his photograph around the world to show the abuses of slavery.

Although the founders had hoped that slavery would die out on its own — and although the importation of slaves became illegal in 1808 — the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 pumped new life into the institution. Between 1790 and 1830, the slave population in the United States nearly tripled.

Largely concentrated in the South, slaves lived grueling lives of uncertainty, violence, and forced labor. Families were routinely broken up as parents and children were sold to other owners. An ex-slave named Pete Bruner recounted being whipped with “a piece of sole leather about 1 foot long and 2 inches wide, cut…full of holes and dipped…in water that was brined.”

Another man remembered seeing slaves at a neighboring plantation: “I’ve seen their clothes sticking to their backs, from blood and scabs, being cut up with de cowhide. [The plantation owner] just whupped dem because he could.”

Although slavery was largely concentrated in the South, business interests in the North supported the institution, as did powerful pro-slavery forces in Washington D.C.

Wikimedia CommonsPlantation slaves planting sweet potatoes circa 1862 or 1863.

Formation Of The Underground Railroad

No one knows exactly when the Underground Railroad formed. Slaves had fled plantations since before the country’s independence, and the abolition movement can claim similar roots.

In 1796 a slave named Ona Judge escaped the plantation of America’s most famous founding father and first president, George Washington. A couple decades prior, in 1775, the world’s first abolition movement formed, and another famous founding father, Benjamin Franklin, became its president in 1787.

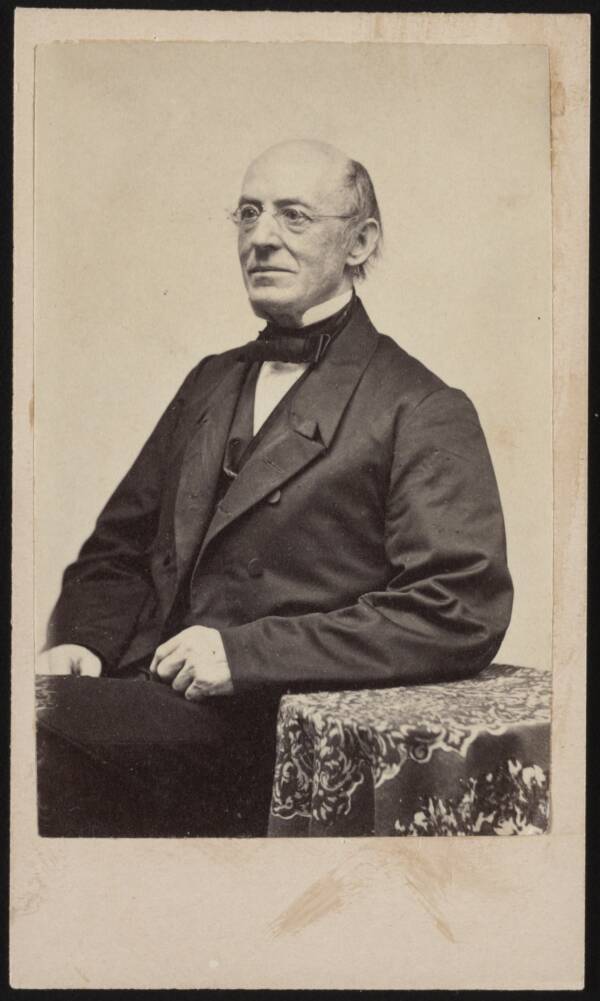

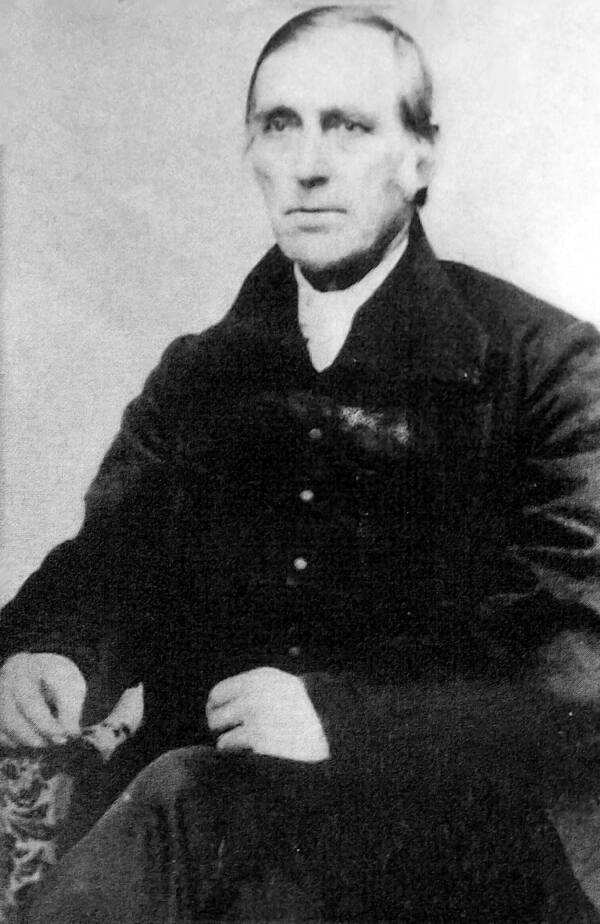

Wikimedia CommonsWilliam Lloyd Garrison, editor of the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator.

The desire to escape and the determination to end slavery laid the foundations for the Underground Railroad. And the need for secrecy quickly became paramount. The 1793 Fugitive Slave Law punished those who helped slaves with a fine of $500 (about $13,000 today); the 1850 iteration of the law increased the fine to $1,000 (about $33,000) and added a six-month prison sentence.

By the 1840s, Americans increasingly understood the term “underground railroad.” In an editorial in The Liberator, an abolitionist newspaper run by William Lloyd Garrison, a Canadian citizen called for a “great republican railroad…constructed from Mason and Dixon’s to the Canada line, upon which fugitives from slavery might come pouring into this province.”

By 1840 the New York Times noted: “[the term Underground Railroad] designate[s] the organized arrangements made in various sections of the country, to aid fugitives from slavery.”

How The Underground Railroad Operated

The Underground Railroad operated using many of the same terms as an actual railroad. Safe houses were called “stations” or “depots”, and run by “station masters.” People with active roles within the organization — those who risked their lives to lead slaves to safety—were called “conductors.”

Wikimedia CommonsAn 1850 map of slave states and territories (green) versus free ones (red).

Conductors, largely freed blacks themselves, guided fugitives north. They often took great risks like sneaking onto plantations to meet up with a group of people.

But often, as historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. notes, slaves had to make their way north alone. “Fugitive slaves were largely on their own until they crossed the Ohio River or the Mason-Dixon line, thereby reaching a Free State.” Gates wrote. “It was then that the Underground Railroad could take effect.”

Even though the fugitive slaves had made it north, they were far from safe. Abolitionism and association with movements like the Underground Railroad were severely unpopular in the decades leading up to the Civil War. And with the passage of the 1850 law, punishment for helping fugitives applied nationally, not just in the South.

So the journey went on in secret. Fugitive slaves would move at night and take refuge in “stations.” A message would be sent to the next station master, alerting them of incoming “cargo.”

According to Gates, in an 1885 newspaper in Oberlin, Ohio, the Underground Railroad was described as “the 19th century’s equivalent of Grand Central Station.”

In reality, the organization was scattered, unorganized, and deeply secret — and everyone knew the risks involved.

The Main Participants Of The Underground Railroad

Many of the main participants in the Underground Railroad were freed blacks or former slaves working in concert with white abolitionists. Gates calls the railroad “perhaps the first instances in American history of a genuinely interracial coalition.”

Still, while recognizing the contributions of white abolitionists, especially Quakers, Gates also makes the point that the railroad was “predominantly run by free Northern African Americans.”

Swarthmore CollegeWilliam Still of Philadelphia was a major conductor on the Underground Railroad.

One such man was William Still, a freed black who helped hundreds of fugitive slaves to safety. One of the organization’s most active station-masters, Still is often called the “Father of the Underground Railroad.”

Still also kept a careful record of those he helped. In 1872, nearly a decade after the end of the Civil War, he published his book The Underground Railroad, which recounted his own work helping slaves to freedom, as well as the personal stories of those fugitive slaves.

“They were determined to have liberty even at the cost of life,” Still wrote.

One woman that Still helped was Araminta Ross, who later changed her name to Harriet Tubman. With the help of a white abolitionist, Tubman escaped slavery in 1849.

“When I found I had crossed that line, I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person,” Tubman recounted in Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman by Sarah Hopkins Bradford. “There was such a glory over everything; the sun came like gold through trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in Heaven.”

Tubman made it to Philadelphia with the help of Still, and turned around a year later to help other slaves to safety. Although the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 made Tubman’s work as a conductor much riskier, she persisted.

Library of CongressHarriet Tubman circa 1868 or 1869. After President Lincoln abolished slavery with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, Tubman became a spy for the Union Army and led a military raid in South Carolina.

In 13 trips to Maryland, Tubman helped 70 slaves escape, and told Frederick Douglass that she had “never lost a single passenger.”

Other prominent members of the Underground Railroad included a white abolitionist Quaker named Levi Coffin, who helped thousands of people flee through Ohio; John Parker, a slave who bought his own freedom and made numerous risky incursions onto Kentucky plantations to help slaves escape; and the Reverend John Rankin, who used the location of his home on the Ohio River to flash a light to the other side, indicating that fugitive slaves could safely cross.

“Every night of the year saw runaways, singly or in groups, making their way slyly to the country north,” recalled Underground Railroad conductor John Parker in his autobiography. “Traps and snares were set for them, into which they fell by the hundreds and were returned to their homes. But once they were infected with the spirit of freedom, they would try again and again, until they succeeded or were sold south”

The End Of The Line: War Begins

The question of slavery and its spread dogged American politics throughout the 19th century. Intense emotions stormed on both sides. White, slave-owning leaders in southern states saw the institution as ordained by God, and although abolition remained deeply unpopular in the north, the more industrial states above the Mason-Dixon line sought to at least contain the spread of slavery.

Wikimedia CommonsLevi Coffin’s Indiana home was known as the Underground Railroad’s “Grand Central Station.”

Then, an Illinois lawyer named Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860 — with virtually zero support from southerners. Far from an abolitionist, Lincoln believed that slavery should be contained, not eliminated. But his election broke the dam of emotion around the issue that had built during the preceding decades.

After Lincoln’s election, South Carolina announced its intention to secede. In Lincoln’s first inaugural address, he tried to reassure the South.

“I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists,” he declared. “I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.” At this point, however, seven states had already left the Union. Four more followed suit after Lincoln was sworn in — and the Civil War began.

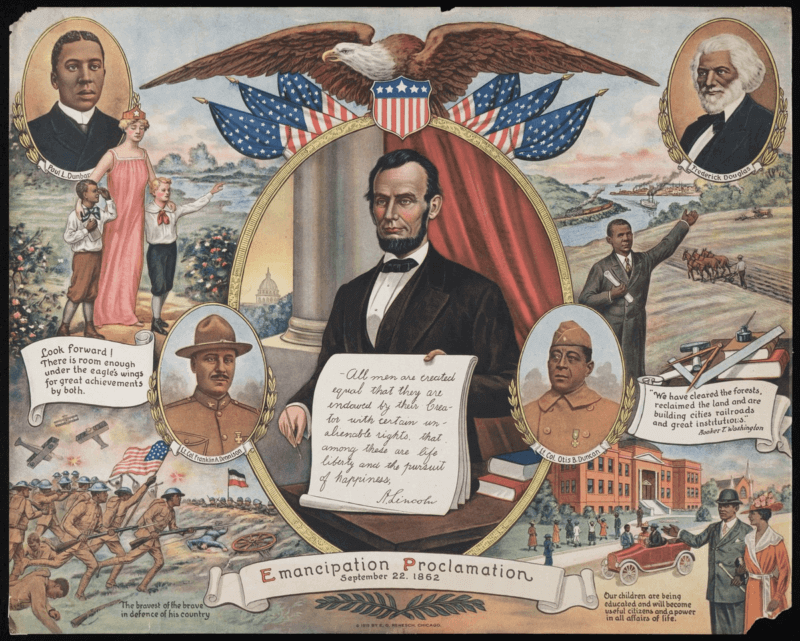

Slaves continued to flee as war raged, and the Underground Railroad helped where it could. On Jan. 1, 1863, Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, which freed slaves within the Confederacy. With that, the end of the war in 1865, and the passage of the 13th amendment that same year, which abolished slavery throughout the country, the necessity of the Underground Railroad ceased to exist.

How many slaves managed to escape using the Underground Railroad? Exact figures are impossible to know, but some estimates suggest that between 1810 and 1860, about 100,000 fugitive slaves underwent the risky journey north to safety — and to freedom.

Wikimedia CommonsAt the urging of black leaders, President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, officially abolishing slavery in the United States and effectively putting an end to the Underground Railroad.

What Is The Legacy Of The Underground Railroad Today?

The Underground Railroad has a complicated legacy today, as well as a resurgence in popular culture. Gates writes that many myths exist around the concept of the Underground Railroad, based largely on the work of Wilbur Siebert’s The Underground Railroad: From Slavery to Freedom.

Both Gates and historian David Blight point out that Siebert’s 1898 account of the Underground Railroad emphasizes the role of white conductors helping “nameless blacks to freedom.” Siebert, Gates notes, also portrayed the system as organized and extensive — a myth that extends to today.

The imbalance of legacy when it comes to the Underground Railroad can be seen in the fact that William Still’s book came out in 1872 — a full 26 years before Siebert’s. And yet Siebert’s account of the Underground Railroad, based largely on interviews with surviving white abolitionists and their children, held more sway over the American conscious than Still’s collection of stories from the fugitive slaves themselves.

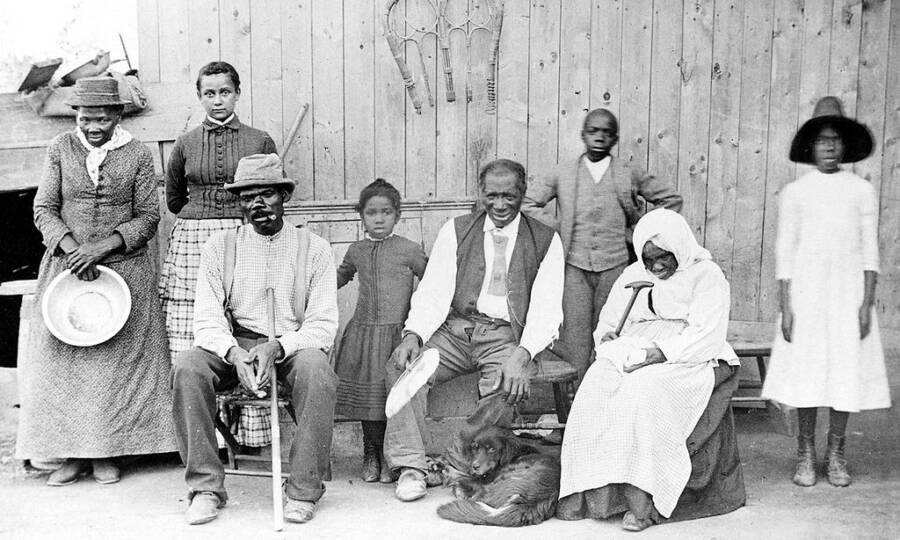

Wikimedia CommonsUnderground Railroad “conductor” Harriet Tubman (left) with family and friends, circa 1887.

But that narrative has begun to shift. Colson Whitehead’s 2016 novel, Underground Railroad, morphs the metaphorical into the physical, describing a real railroad — yes, underground — that fugitive slaves took to get north.

Whitehead’s novel also lays bare the stakes of the journey. Although the Underground Railroad is described in schools as a triumph of American history, he underlines the terror of escape, the depravity of slavery, and the terrible violence that befell those who did not succeed in their flight.

Harriet Tubman, indisputably a champion of the Underground Railroad, will soon get her due as well. Although efforts to put her face on the $20 bill have stalled (she would replace Andrew Jackson, who’s most famous for initiating the Trail of Tears) Tubman is the feature of the 2019 film Harriet.

Harriet will depict Tubman’s escape from slavery and transformation into one of America’s most prominent abolitionists and Underground Railroad conductors.

Today, the shores of the Ohio River are silent. Green and peaceful, they do not betray the secrets of thousands of people who swam or boated across dark waters, in a desperate search for a light on the other side.

After learning about the history of the Underground Railroad, read the story of Cudjo Lewis, the last living slave brought to America. Then explore the and the tale of Ellen and William Craft, slaves who escaped to freedom disguised as a slave owner and his valet.