New York's Stonewall riots of 1969 saw members of the LGBTQ community clash with police in what's widely known as the catalyst for the modern gay rights movement.

The Stonewall riots put gay rights on the map — but when the first shot glass was thrown, nobody involved knew they were going to alter the course of history.

Welcome To The Stonewall Inn

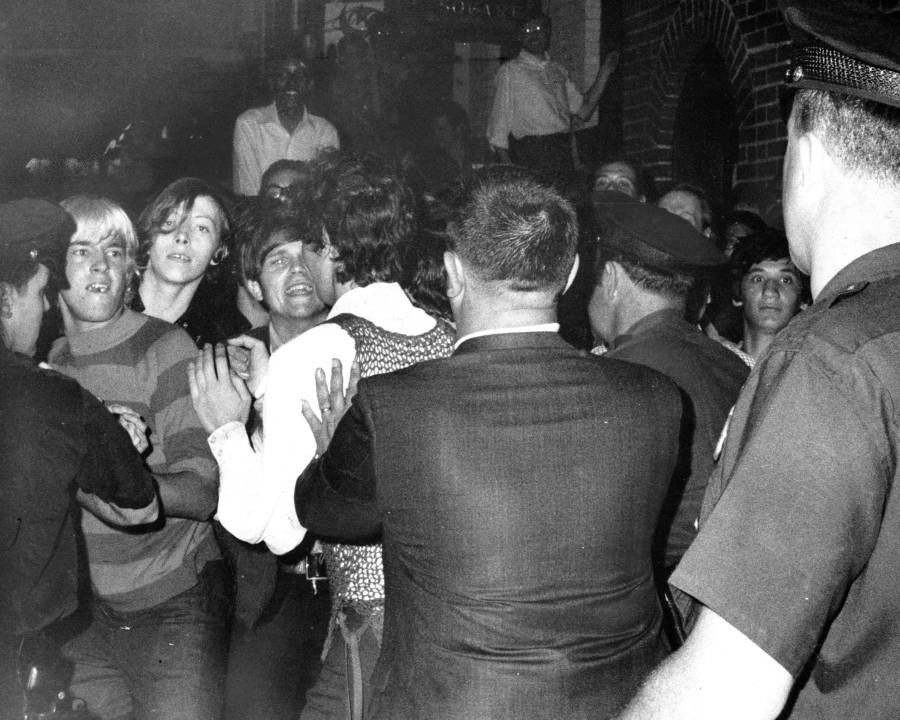

NY Daily News Archive via Getty ImagesCrowds clash with police just outside the Stonewall Inn at 53 Christopher Street during the Stonewall riots.

It did not look like a place that could start a revolution.

It was a dive bar — but even that characterization was optimistic, since it couldn’t get a liquor license. Its drinks were bootlegged and heavily watered down. The contents of no bottle ever matched its label. There were no fire exits, and there was no running water; glasses were rinsed and immediately reused.

But in that Greenwich Village tavern, there was music, there was dancing, and there was freedom. It was one of the only places for New York’s gay community to socialize and truly be themselves.

For this, they had the Mafia to thank.

In 1969, being gay was as illegal as stealing cars or embezzling money. Public displays of affection or dressing in drag could result in charges of gross indecency and lewdness, and the penalty was arrest or a meeting with a billy club.

DeviantArtThe Stonewall riots were just the beginning; the fight for equality continues today.

As with all illegal activity happening in its purview, the Genovese crime family wanted in. The market, they knew, was there: at the time, New York City had the largest gay population in the United States.

So the mob became the financial backer of New York’s underground gay scene, funding the 181 Club, the Howdy Club, and The Stonewall Inn. The crime family’s involvement allowed the fledgling gay bars to sidestep the biggest obstacle in their path: law enforcement.

The state of New York was deeply committed to upholding anti-sodomy laws — so committed, in fact, that it set about entrapping potential lawbreakers. Police vice squads pursued LGBTQ individuals, bought them drinks, and made offers — and then arrested those who accepted.

The Mafia couldn’t pay off every police officer in the city. By the mid 1960s, over 100 men were being arrested per week and it was in that climate that the raid on the Stonewall Inn took place.

The Raid On The Stonewall

Whose Streets Our StreetsThe Stonewall Inn, site of the Stonewall riots, as depicted in the 2015 movie Stonewall.

In the chaotic aftermath of the night of June 27, 1969, there were two things everyone who had been at the Stonewall Inn could agree on: what happened had happened fast, and it had been entirely spontaneous.

When police burst through the doors at 1:20 AM, the bartender knew something had gone wrong. He had thought the establishment was in the clear that night; though there had been rumors and a recent spate of raids — notably those on the Snake Pit and the Sewer — he hadn’t received a tipoff that the Stonewall would be hit.

To this day, nobody knows why he didn’t. Some speculate that the Stonewall was behind on its payments to dirty cops. Others suggest that the Mafia management had become more interested in blackmailing wealthy Stonewall patrons than selling liquor at a dive bar.

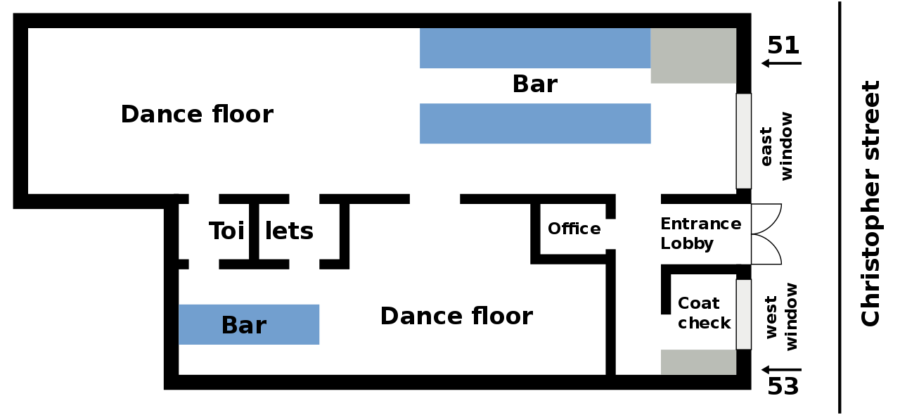

Wikimedia CommonsThe layout of the Stonewall Inn, where the Stonewall riots began.

Either way, the raid caught the Stonewall staff entirely unprepared. There was no time to hide the liquor and no chance to warn patrons. It was the club’s worst nightmare.

The patrons were told to line up against the wall and be ready to produce their identification. Those whose gender didn’t appear to match their driver’s license would be arrested, and those without identification would be taken into another room to have their sex verified.

FlickrThe sign of the Stonewall Inn, site of the 1969 Stonewall riots.

It was a severe blow. The Stonewall Inn was a sanctuary for drag queens, who were not always welcomed even at other gay bars. It was also a favorite haunt of underage and homeless members of the LGBTQ community.

In short, on the morning of June 28, the Stonewall was full of people who had every reason not to want to show their IDs.

The Stonewall Riots

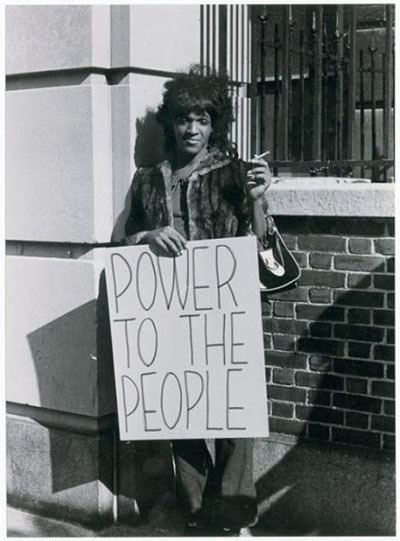

TumblrMarsha P. Johnson, credited with inciting the Stonewall riots.

It started with the drag queens. Unwilling to accompany officers into the back room to have their sex checked, they stayed where there were. Other patrons refused to show their identification cards. When it was decided that everyone would be taken to the police station, Marsha Johnson, a black trans woman, proclaimed her rights by throwing a shot glass into the mirror.

Outside the Stonewall, a crowd was gathering. Many of those who had managed to escape lingered, waiting for news of their friends. Other members of the gay community joined them.

Rumors made their way out to the waiting onlookers: those inside, it was said, were being beaten by cops. The crowd began to perform, taunting police officers with exaggerated salutes as the first of the arrested emerged from the bar in handcuffs.

Stormé DeLarverie, known as the Rosa Parks of the gay community, brought tensions to a boiling point. She fought with police officers and was clubbed for her trouble. As she was thrown into the back of a patrol wagon, she turned to the crowd and shouted, “Why don’t you guys do something?”

TumblrTwo of the many leaders in the Stonewall riots, Marsha P. Johnson and Stormé DeLarverie.

With that, the floodgates broke. New York’s gay community could indeed do something — after all, the crowd vastly outnumbered the police.

They threw pennies, beer bottles, cans, and cobblestones at law enforcement officials. Tires were slashed, and as protestors fell to the ground, more surged forward to take their place. Parking meters were pulled from the pavement and used as battering rams.

In the chaos, detainees began to escape and join the fight. The police retreated to the bar, which patrons immediately set on fire.

The Immediate Aftermath Of The Stonewall Riots

Johannes Jordan/Wikimedia CommonsThe Stonewall Inn. 2008.

By 4:00 that morning, the Stonewall Inn was in ruins and the streets were quiet. Both police and rioters had been hospitalized, and the violence, it seemed, was over.

But things were only just beginning. In true Stonewall fashion, people turned out again the following night, and the night after that, taking to the streets time and time again. What had once been secret was now out, and there was no shoving it back in the closet.

The Stonewall was open to greet them.

Stonewall patron and protester Michael Fader explained the atmosphere, saying:

“We all had a collective feeling like we’d had enough of this kind of shit. It wasn’t anything tangible anybody said to anyone else, it was just kind of like everything over the years had come to a head on that one particular night in the one particular place, and it was not an organized demonstration… Everyone in the crowd felt that we were never going to go back.

We weren’t going to be walking meekly in the night and letting them shove us around—it’s like standing your ground for the first time and in a really strong way, and that’s what caught the police by surprise. There was something in the air, freedom a long time overdue, and we’re going to fight for it. It took different forms, but the bottom line was, we weren’t going to go away. And we didn’t.”

Stonewall The Movie

VultureA still from the 2015 film Stonewall.

The Stonewall Inn made headlines again in 2015 when its story came to the silver screen — but not in a good way.

The trailer’s release turned initial enthusiasm to anger and dismay. Outrage from the LGBTQ community took the form of 22,000 signatures and vows to boycott the film.

Behind the widespread negative feedback was a common theme: casting choice.

Critics said Stonewall depicted brave, cisgender white males as the unsung heroes of the movement. In reality, trans women of color, butch lesbians, drag queens, homeless queer people, sex workers, gay, bi, and pansexual people were the riots’ heart and soul.

The removal of these often “darker” heroes from a film isn’t a phenomenon specific to Stonewall; Hollywood has a long history of minority erasure in film. A study by USC’s Annenberg School of Communication analyzed over 700 films from 2007 to 2014.

The results make a strong case that, in general, roles for disenfranchised people in the entertainment industry haven’t improved over this period of time.

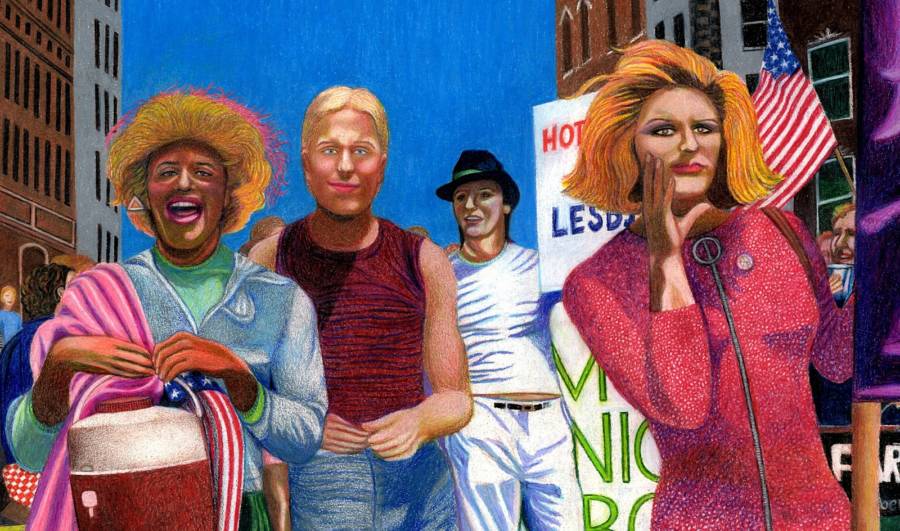

Gary LeGault/Wikimedia CommonsMarsha P. Johnson, Joseph Ratanski, and Sylvia Rivera in the 1973 NYC Gay Pride Parade photographed by Gary LeGault.

The statistics for erasure of queer characters are particularly bleak: after analyzing seven years of film and 4,610 speaking characters, there were only 19 gay characters represented and zero transgender characters. Nearly 85 percent of the gay characters appearing on the big screen were white.

These statistics present a formidable problem in their own right, but especially so since queer women of color actually fronted the Stonewall riots — not the fictionalized white males that the film’s producers decided to prioritize.

Stonewall the movie is a reminder of how far we still have to go. But its heroes — its real heroes — have faith. Today’s interviews with Stonewall rioters are generally optimistic. Things, they say, are still changing. And nobody knows change better than the people who sparked a revolution.

After this look at the Stonewall riots, read up on the Zoot Suit Riots or discover the history of the hippie movement.