On October 12, 1915, British nurse Edith Cavell was killed by a German firing squad for helping some 200 Allied soldiers escape German-occupied Belgium.

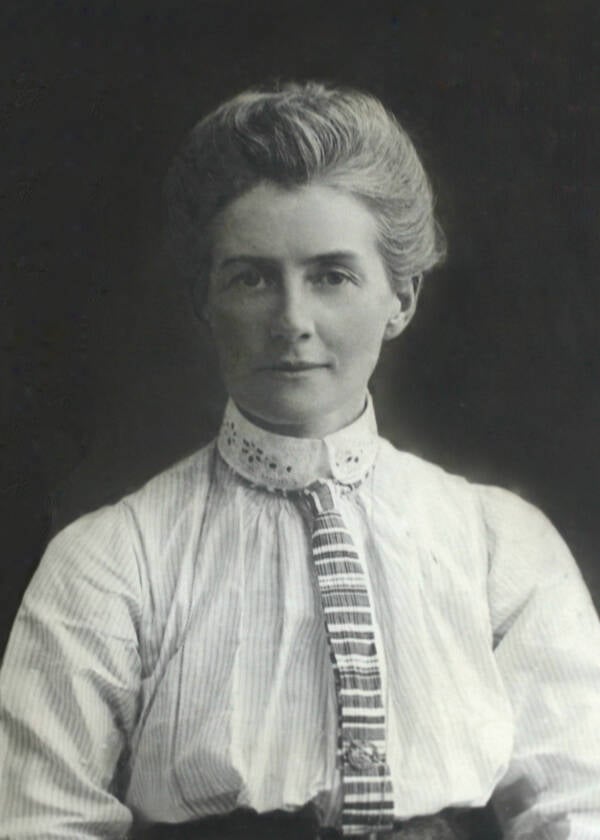

Wikimedia CommonsEdith Cavell was working as a nurse in Belgium when World War I started.

On the morning of October 12, 1915, German soldiers marched a small group of prisoners to Tir National, a former Belgian Army rifle range. The German military chaplain, Pfarrer Le Soeur, took the hand of the only woman among them — a British nurse named Edith Cavell.

“I am glad to die for my country,” she told him. Le Soeur watched as Cavell was blindfolded. Her hands were tied behind her back. Then, the soldiers fired and Cavell fell to the ground.

“When I got home,” Le Soeur wrote, “I felt sick to my soul.”

He was hardly the only one. The execution of Edith Cavell during the darkest days of World War I outraged scores of people — especially in the Allied nations. British author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote: “Everybody must feel disgusted at the barbarous actions of the German soldiery in murdering this great and glorious specimen of womanhood.”

Edith Cavell was seen as virtuous by many. But the Germans maintained that her role in smuggling Allied soldiers out of German-occupied Belgium while working as a nurse in the territory made her guilty of treason. Recent evidence also suggests that Cavell may have had links to British intelligence.

This is her remarkable story.

Edith Cavell’s Path Toward Nursing

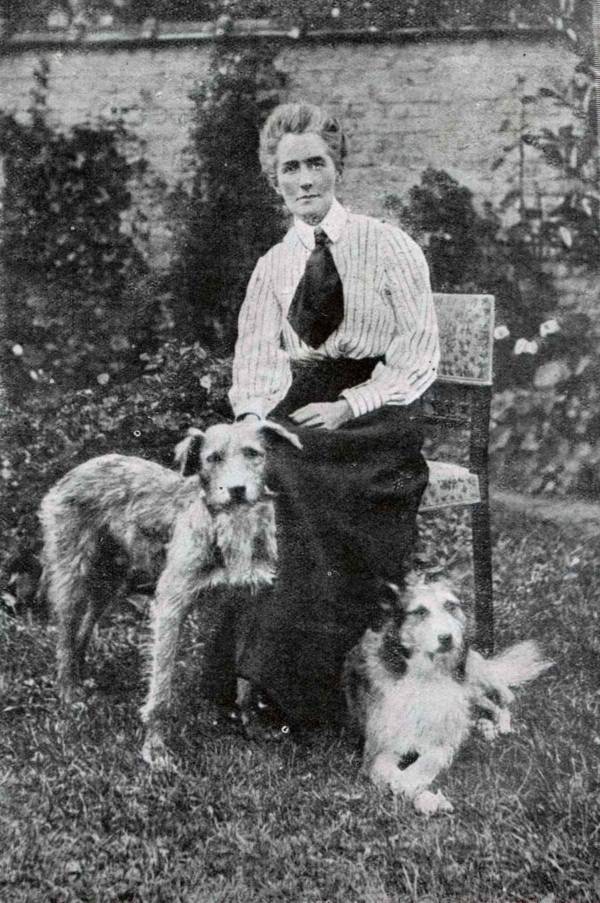

Wikimedia CommonsEdith Cavell in her garden with her two dogs.

Edith Cavell was born on December 4, 1865, in Swardeston, Norfolk, England. She was the eldest of four children and the daughter of a rector, Frederick Cavell, a religious man who insisted that his surname rhymed with gravel and not with hell.

“Do come and stay again soon,” Cavell once wrote to a cousin, “but not for a weekend. Father’s sermons are so long and dull.”

Although her father could be strict, he also gave his children their early education and taught them the values of duty, self-sacrifice, and prayer — lessons that Cavell took to heart. When her father mentioned the need to expand his church to make room for a Sunday school, she and her siblings painted and sold cards to help him raise the funds.

As she got older, Cavell took several significant steps toward her destiny at Tir National. When she showed an aptitude for French at boarding school, her headmistress recommended her as a governess to the Francois family in Brussels, Belgium. And when her father fell ill in 1890, taking care of him convinced Cavell to become a nurse.

From there, everything started to fall into place. Cavell trained at The London Hospital at Whitechapel. She became the assistant matron at Shoreditch. Soon after that, Dr. Antoine Depage, a friend of the Francois family, offered Cavell a job back in Belgium. Cavell agreed. Her fate was set.

Depage had established L’École Belge d’Infirmières Diplômées, also called the Clinique, in May 1907. Nursing was a new industry, casting professional women in a role that had long been occupied by nuns. Depage wanted to modernize nursing in Belgium — and needed good nurses like Edith Cavell.

In accepting his offer, Cavell showed her willingness to break convention in pursuit of what she thought was right. “The old idea that it is a disgrace for women to work is still held in Belgium,” Cavell wrote her mother. “Women of good birth and education still think they lose caste by earning their own living.”

Edith Cavell flourished in Brussels. By 1914, she was working full-time, giving multiple lectures a week, and caring for her two dogs, Don and Jack.

But the clouds of war were gathering on the horizon.

Taking A Stand In German-Occupied Belgium

Imperial War MuseumEdith Cavell (center) sits with nurses that she trained in Brussels. Circa 1907-1915.

When Germany invaded Belgium in August 1914, Edith Cavell was visiting her widowed mother back in England. Cavell could have avoided the war and stayed in Britain. But she insisted on returning to Brussels.

“At a time like this,” Cavell said, “I am more needed than ever.”

By this point, Edith Cavell was in her seventh year as head matron of the Berkendael Medical Institute, a nurse training school. This building was converted to a Red Cross hospital during the war. As wounded soldiers started pouring in, Cavell instructed her nurses to treat all the men equally — regardless of their nationality.

“Each man is a father, husband, or son,” she said. “The profession of nursing knows no frontiers.”

Edith Cavell’s determination to help those who needed it was tested after the Battle of Mons. Then, 150,000 British troops retreated from Belgium — leaving the wounded behind and vulnerable to capture. When two British soldiers were brought to Cavell in September 1914, she agreed to help them.

But Cavell did more than nurse the men back to health. She also helped smuggle them out of Brussels and into the neutral Netherlands — marking the beginning of her quiet resistance to German occupation. As Cavell said herself: “I can’t stop while there are lives to be saved.”

She worked diligently over the next several months to help others. As Germans issued warnings throughout Brussels about what would happen to anyone who aided Germany’s enemies, Cavell ushered some 200 Allied soldiers into her hospital — and helped lead them to safety.

“We shall be punished in any case, whether we have done much or little,” Cavell, aware of the danger, told her accomplices. “So let us go ahead and save as many as possible of these unfortunate men.”

She went to great lengths to remain undetected. The soldiers were signed in as “patients” and had fake identity cards. Those who needed her help memorized a password (“yorc”). Cavell kept her diary sewed inside a pillowcase and even once hid a British soldier inside a barrel of apples to avoid detection by a German officer.

But it wouldn’t be enough.

The Germans had already been eyeing the British nurse with suspicion. And when a French collaborator named Georges Gaston Quien passed through Cavell’s hospital — pretending to be a soldier in need of help — the authorities had enough evidence to arrest her.

The Execution That Outraged The World

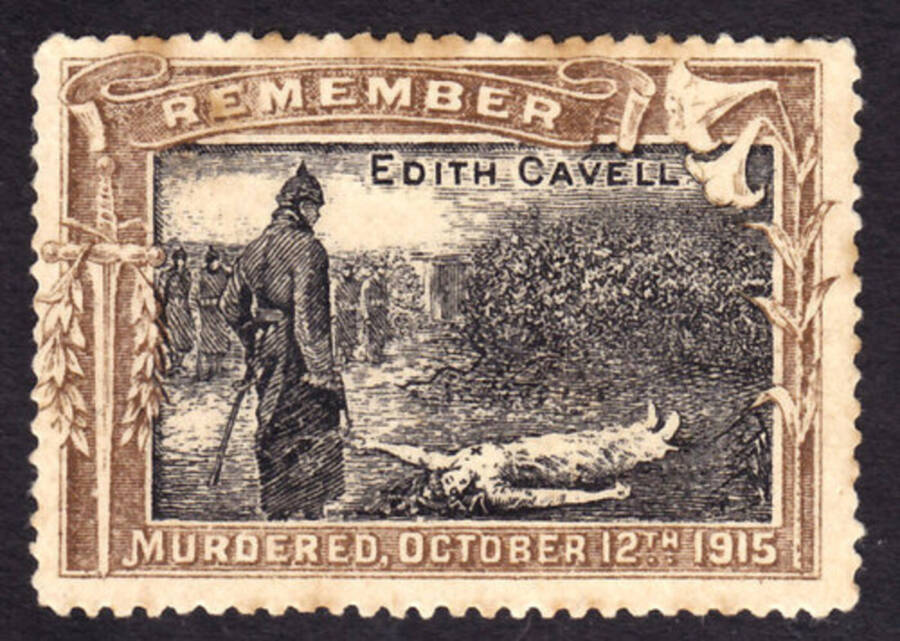

Wikimedia CommonsA postcard commemorating Edith Cavell’s death.

On August 5, 1915, Edith Cavell was arrested by German authorities and sent to the St. Gilles prison in Brussels.

“My aim was not to help your enemy,” Cavell said at her trial in October 1915, “but to help those men who asked for my help to reach the frontier.”

“Had I not helped,” Cavell added, “[the soldiers] would have been shot.”

Unsurprisingly, the Germans were not sympathetic. Cavell — as well as most of her accomplices — were charged with “conducting soldiers to the enemy.” Under German martial law, the punishment was death.

People around the world were outraged. But there was little that could be done. Although the First Geneva Convention set protections for medical personnel, these protections were removed if someone used their position as a “cover” for belligerent action. And across the Channel, British politicians doubted that they held any sway with German authorities.

Wikimedia CommonsEdith Cavell’s hospital was taken over by the Red Cross during the war.

“Any representation by us will do more harm than good,” said Lord Robert Cecil, the Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs.

The United States — still neutral in 1915 — did try to intervene. H.S. Gibson, a U.S. State Department diplomat in Brussels, warned the Germans that killing Edith Cavell would be another black mark against them — a new PR crisis following other heavily criticized events, like the sinking of the Lusitania.

In response, one German official snapped that his only regret was that he didn’t have “three or four old English women to shoot.”

On October 12, 1915, Edith Cavell was executed by a firing squad at Tir National. She was 49 years old when she died.

Library of CongressTir National in Brussels, where Edith Cavell was killed.

At the time, news reports claimed that she had fainted after being blindfolded and that a German soldier shot her while she was lying on the ground. This was contradicted some years later.

The German military chaplain, Le Soeur, described the scene:

“My eyes were fixed exclusively on Miss Cavell, and what they now saw was terrible. With a face streaming with blood — one shot had gone through her forehead — Miss Cavell had sunk down forwards, but three times she raised herself up without a sound, with her hands stretched upwards. I ran forward with the medical man, Dr. Benn, to her. He was doubtless right when he stated that these were only reflex movements… she was killed immediately.”

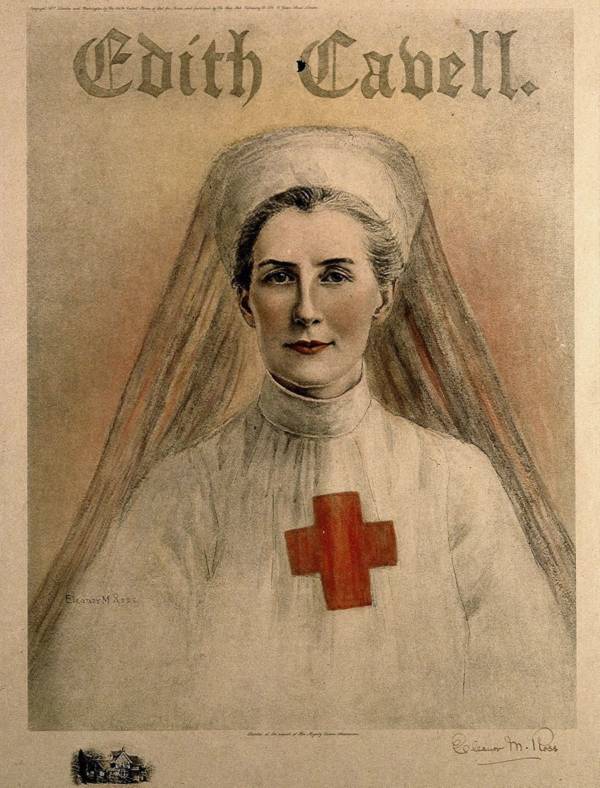

Although the Germans had expected that Edith Cavell’s execution would discourage others from following in her footsteps, it had quite the opposite effect. The British Army experienced a remarkable 50 percent increase in new recruits, leading one novelist to quip: “Emperor Wilhelm would have done better to lose an entire army corps than to butcher Miss Cavell.”

She became an important propaganda tool for the Allied powers — proof of German brutality and a compelling reason to win the war.

When the Allies did win, Cavell’s body was exhumed from Tir National and brought home.

Lingering Questions About Edith Cavell’s Legacy

A. R. Coster/Topical Press Agency/Getty ImagesEdith Cavell’s funeral procession in May 1919 took place after her body was exhumed in Belgium and brought home.

Edith Cavell has long been remembered as a martyr — someone willing to help those who needed it, despite the dangers to her life. But her legacy is not that simple. Nor, according to her living relatives, should it be.

“Despite the posters of a helpless young girl lying on the ground while she is shot in cold blood by a callous German,” said Dr. Emma Cavell, a historian and Cavell descendent, “the truth is that Edith was a tough 49-year-old woman who knew precisely the danger she was placing herself in.”

Dr. Cavell added, “She admitted quite frankly what she’d done, and doesn’t appear to have been afraid of the consequences.”

In fact, Edith Cavell may have known much more than she let on. Cavell’s biographer, Diana Souhami, noted that British intelligence sought to suppress information after Cavell’s death that would suggest she was a British spy. After all, Cavell had become an effective propaganda tool for the British.

Stella Rimington, a former head of M15, confirmed this. “Cavell’s main objective was to get hidden Allied soldiers back to Britain,” Rimington said. “But, contrary to the common perception of her, we have uncovered clear evidence that her organization was involved in sending back secret intelligence to the Allies.”

The men that Edith Cavell helped escape from Belgium carried information about the German military hidden in their shoes and sewn into their clothing back to France and Britain. So, how much did Edith Cavell know?

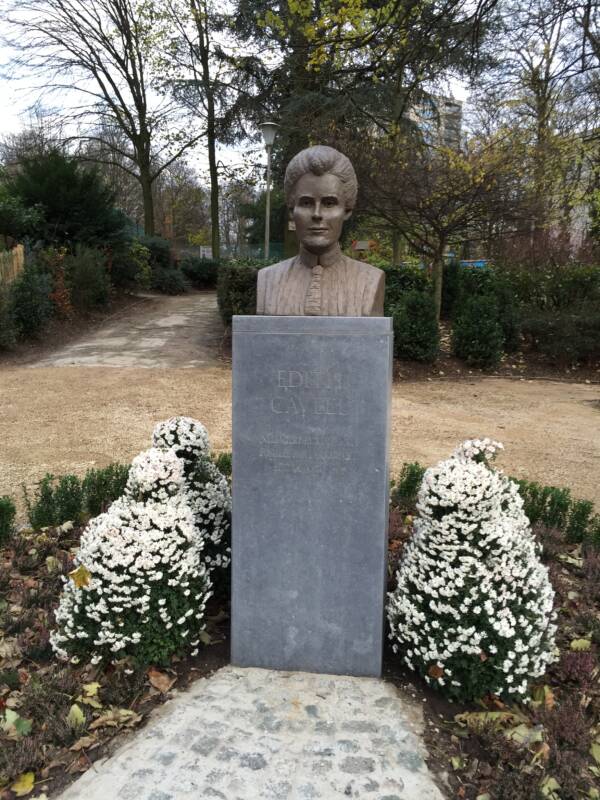

Wikimedia CommonsA statue of Edith Cavell near the St. Gilles prison.

Richard Maguire of the University of East Anglia believes that Cavell was working for British intelligence — if not directly, then indirectly, happy to look the other way as the soldiers smuggled out military secrets.

“Does this make Cavell a spy?” Maguire asked. “That depends upon your definition of the term. I would argue that the balance of evidence suggests that she was certainly an active and very successful agent for the British government’s war effort.”

Without any written confirmation from Edith Cavell herself, it’s impossible to pinpoint her true motivation in helping soldiers escape Belgium.

But her actions speak louder than words. Thanks to Edith Cavell, hundreds of soldiers were able to escape from occupied territory and make it home.

“Patriotism is not enough,” she said, on the night before her execution. “I must have no hatred or bitterness toward anyone.”

After reading about Edith Cavell, check out some more of history’s most extraordinary war heroes. Then, take a look at the real-life Rosie the Riveters.