Taking place thousands of years ago, Aristophanes' theory on love is more sophisticated and progressive than a lot of modern politicians.

A symposium scene on a 5th century BCE Greek cup currently housed in the State Antiquities Collection in Munich, Germany. Source: Wikimedia

Written 2,400 years ago, Plato’s philosophical novella, Symposium, includes one of the weirdest – and most charming – explanations of why people fall in love ever invented. Plato gives this trippy exegesis to the playwright Aristophanes, who appears as a character in the book.

Before turning to Aristophanes’s odd speech, let’s set the stage. First, we’re at a dinner party. Wealthy Athenian men have gathered, as they often did, to drink wine, eat, philosophize, and carouse with women, younger men, or each other. On this (fictional) occasion, the guests are all playwrights and philosophers and they include Plato’s idol Socrates. As the night progresses, the conversation turns to the meaning of love.

In the Greek world, two-and-a-half millennia ago, writers and thinkers often viewed love with suspicion because it aroused passions that could drive a man to abandon responsibility, obsess, and/or go mad. But the guests at this symposium seek to find what is praiseworthy about love. One man says it makes lovers brave, particularly homosexual soldiers who serve alongside each other in the army; their love would make them more valiant than the loveless. Later Socrates suggests that learning to love is a step toward discovering higher beauty and truth, such as offered by philosophy.

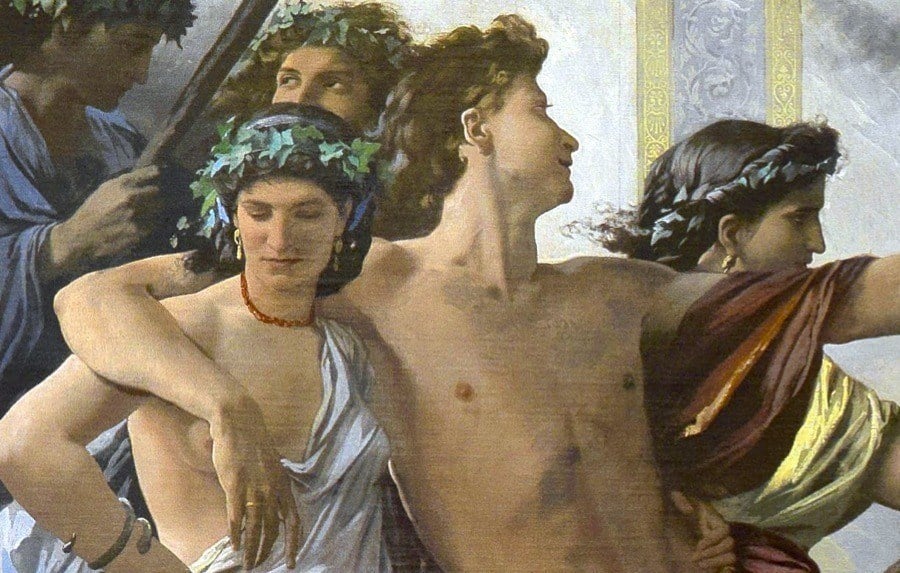

Detail from the 1869 painting ‘Plato’s Symposium’ by Anselm Feuerbach on display at the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, one of Germany’s more prestigious art museums. Source: Cultural Institute

The most memorable speech of the night – and the strangest – comes from Aristophanes. After recovering from a bout of hiccups, the playwright starts his speech. Instead of an intellectual discourse, he tells a story, a myth of the origins of love.

Aristophanes says that at the beginning of the world human beings looked very different:

“Primeval man was round, his back and sides forming a circle; and he had four hands and four feet, one head with two faces, looking opposite ways, set on a round neck and precisely alike… He could walk upright as men now do, backwards or forwards as he pleased, and he could also roll over and over at a great pace, turning on his four hands and four feet, eight in all, like tumblers going over and over with their legs in the air; this was when he wanted to run fast.”

These weird, fused humans had three sexes, not the two we have today. Some were male in both halves, some were female in both haves, and others had one male half and another female half. According to this tale, they were more powerful than today’s frail human creatures. Aristophanes says, “Terrible was their might and strength, and the thoughts of their hearts were great, and they made an attack upon the gods.”

The gods met to discuss how they would deal with these circular attackers. Several suggested all-out slaughter. But Zeus said that humanity simply needed to be humbled, not destroyed. The gods decided to sever the humans in two. “And if they continue to be insolent and will not be quiet,” said Zeus, “I will split them again and they shall hop about on a single leg.”

The gods halved the humans. And so now, in this new age of split selves, the two halves roam the face of the earth searching for one another. Male searching for male, female searching for female, and male and female searching for each other – it is all part of the same story, according to the playwright. And finding that other, original part of yourself… That is love. As Aristophanes concludes,

“After the division the two parts of man, each desiring his other half, came together, and throwing their arms about one another, entwined in mutual embraces, longing to grow into one.”