Source: New York Daily News

There was a time when all Hillary Rodham Clinton wanted to do was finish her freakin’ dissertation.

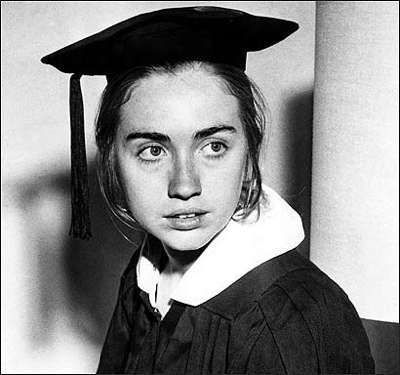

The year was 1969. The place, Wellesley College. Hillary Rodham was not just trying to finish her senior thesis, but also prepare to speak at her graduation: the first student to be asked to do so in the university’s history. Even at twenty-two, there was something about her that made people pay attention.

In the myriad biographies that have been written about Hillary, Gail Sheehy was the only writer to give us a portrayal of the woman who would become HRC as a somewhat clumsy, geeky undergrad who escaped the conservative trappings of her upbringing to become a vocal, steely, liberal before that was socially cool.

In Sheehy’s book, Hillary’s Choice, she interviewed several of Hillary’s former classmates and childhood friends. Most of them remembered her as being pugnacious from the start and clearly uninterested in her appearance; a stance that has remained a major element of her media strategy even as a middle-aged woman. One of her honors classmates, John Peavoy, summed it up for Sheehy in one sentence:

“The reason Hillary didn’t date much was because she was so formidable.”

Source: The Boston Herald

Reflecting on both her senior thesis, An Analysis of the Alinsky Model —a lofty critique of the work of radical Saul Alinsky—and the controversial speech she gave at Wellesley’s 1969 Commencement, formidable was a fair assessment of Hillary Rodham. In front of her professors, 400 classmates, their families and the distinguished guests at the commencement ceremony, she went a bit off-book during her formally prepared speech to criticize the main speaker at the commencement, Senator Edward Brooke:

“Part of the problem with empathy with professed goals is that empathy doesn’t do us anything. We’ve had lots of empathy; we’ve had lots of sympathy, but we feel that for too long our leaders have used politics as the art of making what appears to be impossible, possible.

What does it mean to hear that 13.3 percent of the people in this country are below the poverty line? That’s a percentage. We’re not interested in social reconstruction; it’s human reconstruction. How can we talk about percentages and trends? The complexities are not lost in our analyses, but perhaps they’re just put into what we consider a more human and eventually a more progressive perspective.”

Source: Life Magazine

Those who had come to know Hillary over her four years at Wellesley (and even those who had known in her childhood) couldn’t have been surprised, but those who recall that moment where she launched into an eloquent, improvised attack on the Senator would classify it as a “Hoe, don’t do it” situation. But do it she did—segueing seamlessly into her prepared speech and receiving a standing ovation at the end—which lasted several minutes.

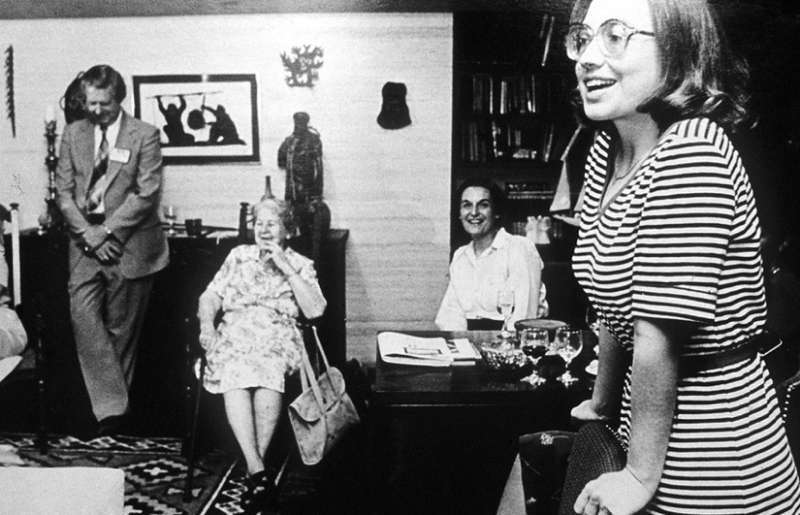

The speech garnered her national attention, and photographs taken at the time for Life Magazine by Lee Balterman, gave the U.S.—and the world—their first look at Miss Rodham. Balterman’s hand-written note to the publisher simply stated, “‘Had to go for nothing more than informal portraits, but should be some good expressions & hand gestures, etc… Her glasses helped.’”

Thus, the attention paid to her appearance began in earnest. But, so too did people begin to pay attention to her mind—one that was still struggling to figure out who she wanted to be.

Source: The Telegraph

Throughout her years at university and somewhat beyond, Hillary continued a friendly correspondence with her friend, John Peavoy. In her letters to him, we get a glimpse of her inner-struggle, developing sense of self and all the typical angst of the twenty-something; which seem not to have changed much whether it’s 1975 or 2015.

In one such letter to Peavoy, she described herself rather clinically as having tried on several personas: “educational and social reformer, alienated academic, involved pseudo-hippie, political leader—or compassionate misanthrope.” In subsequent letters over the years, the identity crisis continued and was often coupled with early-year, mid-winter bouts of depression. In her letters she struggled to define “happiness” in operational terms, always putting the word happiness in quotations, as if to further separate it from her personal lexicon.

But a singular moment in history charted twenty-something Hillary Rodham on a clear path toward a life of political service: the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. As many of her classmates did, she found herself vacillating between fits of tears and anger at the growing turmoil and violence. And she began to speak up, louder than she ever had before.

The uprising was echoed by the students at Wellesley and, truthfully, youth nationwide. She began to acquire a reputation of being bristly, and at times downright cutting. One classmate at Wellesley simply said of her, “She doesn’t suffer fools gladly”—and perhaps that would have been an understatement. Even her own mother, Dorothy Rodham, admitted that Hillary was capable of being very impatient with those who couldn’t keep up with her. She was on a path and she had a plan; not much could slow her down.

Source: The Telegraph