History is made by people, with much of it consisting of the working out of already latent and often inevitable human trends. Sometimes, however, history takes a sharp turn away from its ordained path in response to a single individual’s will. Sometimes you can go back to a particular moment in history and say that if it hadn’t been for one person, things would have been very different. This is the story of five of those people.

Ghengis Khan Prunes Asia Like A Garden

Source: Flickr

History should never have heard of Genghis Khan. As a twelve-year-old boy, the future Khan (then known as Temujin) lost his father, a tribal chieftain, when he was poisoned by Tartars. Things like that usually ended with the slain chieftain’s whole family being wiped out, but Temujin escaped into the wilderness with his mother and a few loyal supporters.

Source: Flickr

As seen above, Mongolia isn’t a really forgiving place for displaced refugees. They survived, though, and young Temujin came roaring back into Mongolian politics in the late 12th century with the aim of uniting all of his homeland’s scattered tribes.

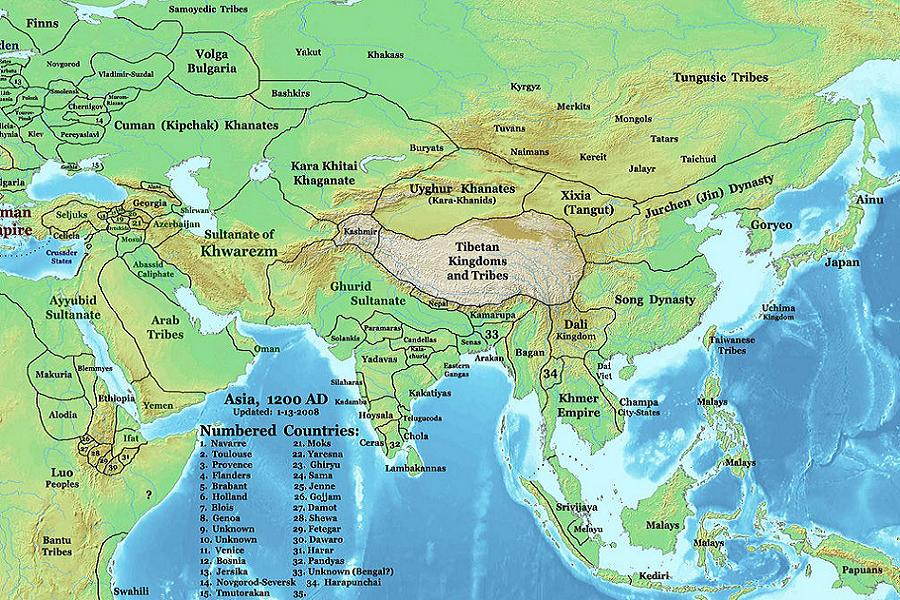

Asia in the year 1200 was a hodgepodge of overlapping empires and principalities. Smaller kingdoms abounded, such as those created by the crusader knights in Syria and Lebanon. Nobody had any idea what was about to hit.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Mongol Horde descended on the world’s largest continent like a plague of locusts. They hated cities, which could be profitably converted into pastureland for their ponies, so they erased them everywhere they went. An anonymous advisor urged the Great Khan to spare the Chinese for tax purposes; this is the reason why people still reside in northern China today. No such luck prevailed in Iran, where the Mongols burned the cities, smashed the irrigation networks, and killed—at a first approximation—everybody.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Before the Mongols, Islamic lands—Baghdad in particular—were learning havens. Science, philosophy, and art thrived under the protection of these stable, prosperous sultanates. All of that was trampled by the hooves of the Mongols’ ponies. The devastation was so total that Iran didn’t return to its pre-Mongol population until the 20th century. Whatever advances history had in mind for the Islamic world of the 13th century would never happen, as the survivors struggled to rebuild their destroyed civilization.

Henry Kissinger Singlehandedly Doubles The Body Count In Vietnam

Source: Mount Holyoke College

Henry Kissinger moved through American politics like a latter-day Talleyrand. Starting as a government lawyer and rising to prominence during Johnson’s term, he became one of the few advisors to make the transition into the Nixon Administration. Unfortunately, the way he did that was by prolonging the war in Vietnam.

Source: History Of PTSD

During the 1968 presidential campaign, Johnson’s chosen political heir, Hubert Humphrey, was widely regarded as having a lock on the race. His ace in the hole was continuing the Paris peace talks, which were expected to bring the increasingly unpopular US involvement in Vietnam to a close. If the Johnson Administration managed to reach agreement with the North Vietnamese in time for the election, Humphrey would be ideally positioned to take home the antiwar vote.

Source: George Washington University

Enter Kissinger. Sensing opportunity in the summer of 1968, Kissinger made contact with John Mitchell, who then served as Nixon’s campaign manager. Using Madame Anna Chennault as a go-between, Kissinger opened a private channel to the government of South Vietnamese president Thieu. Hinting very strongly that the impending peace treaty would be unfavorable to South Vietnam, Kissinger persuaded Thieu to withdraw from talks, effectively sabotaging the peace process.

Source: Outside The Beltway

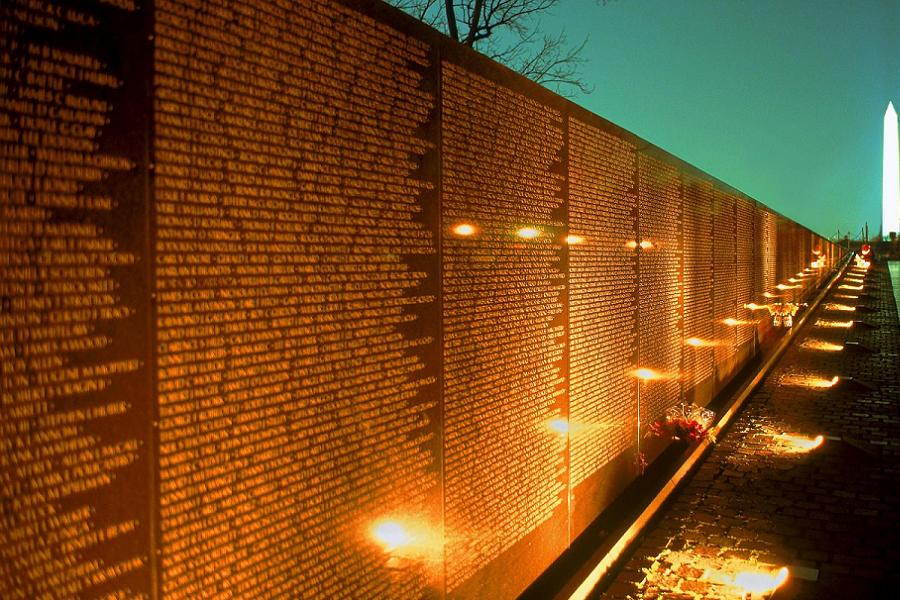

The collapse of negotiations became known as the “October Surprise,” and the consensus among historians is that it played a key role in putting Nixon over the top in the next month’s election. In 1973, peace was agreed to by the parties on terms that were substantially identical to those proposed in 1968. In the five years between those dates, 20,000 Americans and untold Indochinese died. Look at that picture of the Vietnam Memorial Wall. The second half is covered with the names of those who died between 1968 and 1973.