In 19th century England, the social event of the season was a rather gruesome affair.

Liz Lawley/Flickr

Egyptian history and culture have fascinated people the world over for centuries, but in the 19th century the Victorian elite took things to a whole new level with “mummy unwrapping” parties.

If you don’t believe it, keep in mind that these were the guys who took photos with their dead relatives and used the deceased’s hair to make jewelry.

The Context

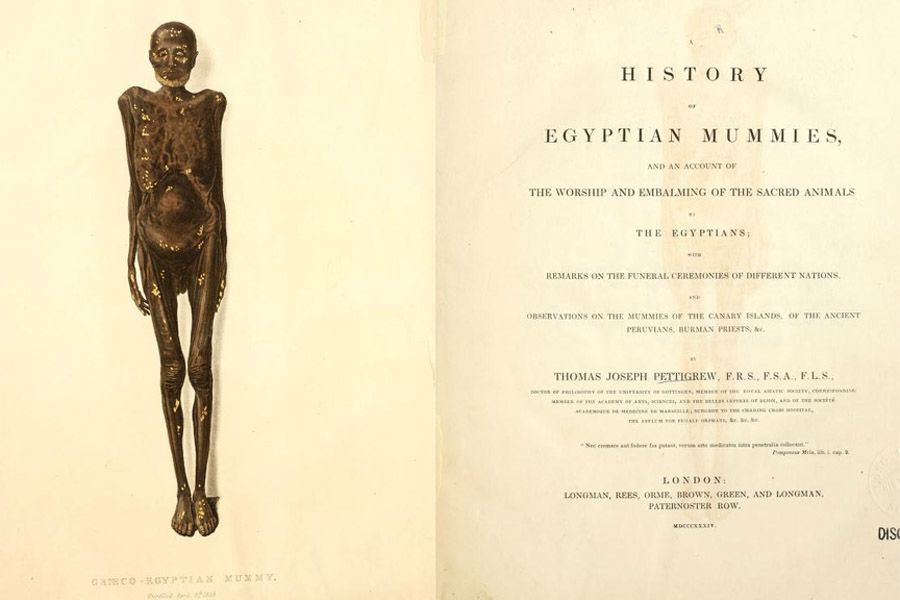

archive.orgThe first pages of Thomas Pettigrew’s book, A History of Egyptian Mummies.

Throughout the 19th century, Europeans experienced a renewed interest in ancient Egypt. While Europeans had purchased mummies since Shakespeare’s time due to their perceived medicinal value, Napoleon’s recent entry into Egypt and Syria — along with the accompanying historical guide Description de l’Egypt — reignited European interest in Egyptian history and culture. This fascination was so pervasive that it had a name: Egyptomania.

Throughout this Egyptomania, European architecture borrowed from Egyptian elements; companies employed Egyptian visual cues in marketing, and Egypt itself saw a boom in tourism. Indeed, wealthy Europeans would travel to the country, often seeking a mummy as a souvenir.

To satisfy this growing demand, Egyptians in popular destinations such as Cairo would ship in mummies from less popular towns. Coming up with mummies wasn’t as difficult as it may sound, given the fact that many Egyptians — not just royalty or the wealthy — practiced mummification for 2,000 years.

Soon enough, the mummy market became so commonplace that French aristocrat and Trappist monk Abbot Ferdinand de Géramb wrote in 1833, “It would be hardly respectable, on one’s return from Egypt, to present oneself without a mummy in one hand and a crocodile in the other.”

The Gathering

ArtMightExamination of a Mummy by Paul Dominique Philippoteaux, circa 1891.

Mummy unwrapping parties would take place soon after the traveler’s return from Egypt. Hosts would send out invitations (“Lord Londesborough at Home: A Mummy from Thebes to be unrolled at half-past Two,” for instance) and guests — inclined to attend what was sure to be the social event of the season — would come in droves to see the mummy.

Of course, the event itself would be quite smelly — but as the mummy unwrapping would take place after dinner and drinking, perhaps guests were less sensitive to the corpse’s odor.

Some of these mummy unwrapping parties would take place in public settings so that more than just the affluent could behold what lay beneath the mummy fabric. According to some, particularly popular were the mummy unwrapping ceremonies held by Thomas Pettigrew, a surgeon whose expertise in Egyptian history and the art of spectacle brought in thousands of visitors.

The End

wscullin/FlickrA partially unwrapped mummy.

Presumably, it eventually dawned on Victorians that unwrapping mummies — and treating human bodies as entertainment — was perhaps not the best way to preserve or even appreciate a given culture, especially for purposes of scientific inquiry. Thus mummy unwrapping eventually fell out of favor, and preservation became the prevailing treatment mummies would receive from the public and scientists alike.

However, some scholars dispute the handful of accounts of unwrapping parties and dispute whether these parties even transpired in the first place. “Unwrapping mummies was not unheard of – but it also didn’t happen in party-like social gatherings,” Ontario’s THEMUSEUM writes. “When mummies were unwrapped, it was done by a researcher in an academic setting, such as a university lecture hall.”

Nevertheless, we’re left with a number of fascinating accounts and at least one place, Bart’s Pathology Museum in London, that conducts a mummy unwrapping re-enactment for the more curious among us today.

No, you won’t encounter a real mummy at Bart’s — but you will come away with an understanding of something more bizarre: the kind of society who would gape at a hundred-plus-year-old corpse for fun.

Learn more about Victorian society with our explainers on Victorian attitudes toward sex and Victorian portraiture. Then, for more on mummies, check out the first ever look inside King Tut’s tomb and sokushinbutsu, the Japanese monks’ art of mummifying oneself alive. Finally, check out the glamorous and gruesome history of the masquerade ball.