Over the course of 500 bloody years, the Native American genocide carried out by both European settlers and the U.S. government left millions dead.

Library of CongressU.S. soldiers bury Native American corpses in a mass grave following the infamous massacre at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1891 when some 300 Lakota Native Americans were killed.

The years-long controversy and protests over the Dakota Access Pipeline that started in 2016 shed new light on the issues that have plagued Native Americans for hundreds of years — and sadly still continue.

The Standing Rock Sioux feared that the pipeline would wreck their lands and spell environmental disaster. Sure enough, the pipeline was completed despite their protests and began carrying oil in June 2017.

Then, a 2020 environmental review confirmed what the Sioux had been saying from the beginning: the leak detection system was inadequate and there was no environmental plan in the event of a spill.

Ultimately, the pipeline was ordered to close in July 2020, bringing four long years of conflict to an end. However, the protracted unrest was about more than the pipeline itself.

At the root of the conflict lay systems of oppression that for centuries worked to wipe out Native American populations and acquire their territorial holdings by force. Through war, disease, forced removal, and other means millions of Native Americans died.

And only in recent years have historians begun to call the United States’ treatment of their Indigenous people what it really is: an American genocide.

Did The United States Commit Genocide?

Library of CongressThis late 19th-century political cartoon depicts a white federal agent squeezing profits out of a reservation while the Native Americans who live there starve.

As historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz said, “genocide was the inherent overall policy of the United States from its founding.”

And if we consider the United Nations’ definition of genocide authoritative, Dunbar-Ortiz’s assertion is right on the mark. The U.N. defines genocide as:

“Any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; and forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Among other things, the colonists and the U.S. government perpetrated warfare, mass killings, destruction of cultural practices, and separation of children from parents. Clearly, many of the actions taken against the Native Americans by the United States settlers and government were genocidal.

Not only did the United States commit genocide against Native Americans, but they did it over a period of hundreds of years. Ward Churchill, a professor of ethnic studies at the University of Colorado calls it a “vast genocide… the most sustained on record.”

In fact, Adolf Hitler, whose genocide of 6 million European Jews shocked the world, took inspiration from the way the United States had systematically eliminated much of their Indigenous population.

In recent years, prominent political figures in the United States have finally begun to acknowledge the Native American genocide and how many Native Americans were killed.

In 2019, California governor Gavin Newsome made headlines when he offered an apology to California’s tribes, saying, “It’s called a genocide. No other way to describe it, and that’s the way it needs to be described in the history books.”

As Americans come to grips with how many Native Americans were killed in the history of the United States, it’s important not to forget or erase this brutal chapter of history.

The Scope Of The Native American Genocide

Wikimedia CommonsLanding of Columbus by John Vanderlyn (1847).

The size of the Native American population before the arrival of Christopher Columbus has long been debated, both because reliable data is extraordinarily hard to come by and because of underlying political motivations.

That is, those who seek to diminish U.S. guilt for the Native American genocide often keep the pre-Columbus native population estimate as low as possible, thus lowering the Native American death count as well.

So, estimates of the pre-Columbus population vary wildly, with numbers ranging from approximately 1 million to approximately 18 million in North America alone — and as many as 112 million living in the Western Hemisphere in total.

However large the original population was, by 1900 that number fell to its nadir of just 237,196 in the United States. So, while it’s hard to say exactly how many Native Americans were killed, that number is most likely in the millions.

Wars between tribes and settlers as well as the taking of native lands and other forms of oppression led to these large death tolls, with death rates for Native American populations as high as 95 percent in the wake of European colonization.

Still, from their first contact with Europeans, they were treated with violence and contempt, and there’s no account of exactly how many Native Americans were killed by the early explorers and settlers.

The Genocide Starts With Christopher Columbus

When Christopher Columbus landed on the Caribbean Island he mistook for India, he immediately ordered his crew to capture six “Indians” to be their servants.

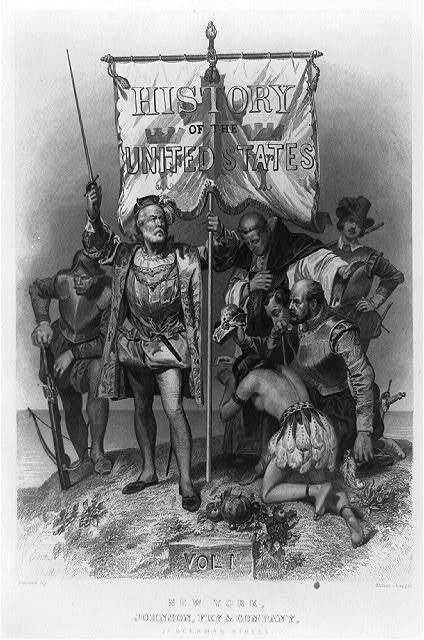

Library of CongressThis title page from an 1858 history of the United States depicts a native woman kneeling at Christopher Columbus’ feet like a savior. In reality, he enslaved, raped, and killed countless Indigenous people.

And as Columbus and his men continued their conquest of the Bahamas, they continued to either enslave or exterminate the Indigenous people they met. On one mission, Columbus and his men captured 500 people who they intended to bring back to Spain to sell as slaves. 200 of these Native Americans died just on the journey across the Atlantic.

Before Columbus, between 60,000 and 8 million native people lived in the Bahamas. By the 1600s when the British colonized the islands, that number had dwindled in some places to nothing. On Hispaniola, the entire Native population had been eliminated, with no accounting for how many Native Americans were killed.

The colonies and explorers who came after Columbus followed his model, either capturing or killing the native people they encountered. From the beginning, the people already living in the “New World” were treated as obstacles, animals, or both, justifying countless Native American deaths.

Hernando de Soto, for example, landed in Florida in 1539. This Spanish conquistador took a number of Indigenous people hostage to serve as his guides while he conquered the land.

Nevertheless, the majority of Native American deaths stemmed from disease and malnutrition attendant on the spread of the European settlers, not warfare or direct assaults.

Disease, the biggest culprit, wiped out an estimated 90 percent of the population.

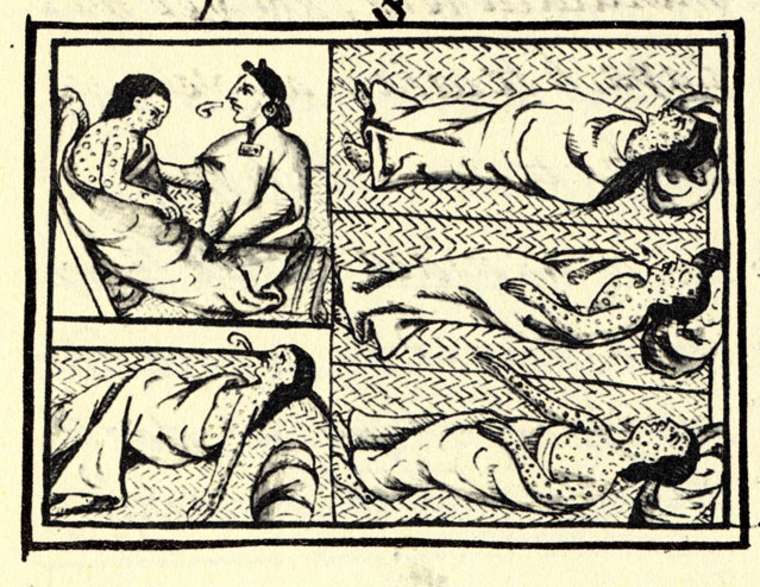

Wikimedia Commons16th century illustration of Nahua Native Americans suffering from smallpox. Some 90 percent of Native Americans were killed by diseases from Europe.

Native Americans had never before been exposed to the Old World pathogens spread by the settlers and their domesticated cows, pigs, sheep, goats, and horses. As a result, millions died from measles, influenza, whooping cough, diphtheria, typhus, bubonic plague, cholera, and scarlet fever.

However, the spread of disease was not always unintentional on the part of the colonists. Several proven instances confirm that in the colonial era European settlers purposefully exterminated Indigenous people with pathogens.

Genocide Against Native Americans In The Colonial Era

Wikimedia CommonsLouisiana Indians Walking Along a Bayou by Alfred Boisseau (1847). Choctaw Native Americans, like those depicted here, were among those forced from their lands starting in the 1830s.

The Native American genocide only gathered steam as more settlers hungry for land arrived in the New World. In addition to coveting native lands, these newcomers saw the Native Americans as dark, savage, and dangerous — so they easily rationalized violence against them.

In 1763, for example, a particularly serious Native American uprising threatened British garrisons in Pennsylvania.

Worried about limited resources and angered by violent acts that some Native Americans had committed, Sir Jeffrey Amherst, commander-in-chief of British forces in North America, wrote to Colonel Henry Bouquet at Fort Pitt: “You will do well to try to inoculate the Indians [with smallpox] by means of blankets, as well as to try every other method, that can serve to extirpate this execrable race.”

Settlers distributed the contaminated blankets to Native Americans, and soon enough smallpox began to spread, leaving a heavy Native American death count in its wake.

Aside from bioterrorism, Native Americans also suffered violence both directly at the hands of the state and indirectly when the state encouraged or ignored citizen violence against them.

Library of CongressCheyenne people taken hostage in 1868 following Custer’s attack on Washita.

According to the 1775 Phips Proclamation in Massachusetts, King George II of Britain called for “subjects to embrace all opportunities of pursuing, captivating, killing and destroying all and every of the aforesaid Indians.”

British colonists received payment for each Penobscot Native they killed – 50 pounds for adult male scalps, 25 for adult female scalps, and 20 for scalps of boys and girls under the age of 12. Sadly, there’s no telling how many Native Americans were killed as a result of this policy.

As the European settlers expanded westward from Massachusetts, violent conflicts over territory only multiplied. In 1784, one British traveler to the U.S. noted that “White Americans have the most rancorous antipathy to the whole race of Indians; and nothing is more common than to hear them talk of extirpating them totally from the face of the earth, men, women, and children.”

While in the colonial era, the Native American genocide was largely carried out on the local level, forced removals in the 19th century that saw a horrific Native American death toll were just around the corner.

Forced Removal On The Trail Of Tears

Library of CongressIn 1830, Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act which allowed the federal government to relocate thousands of tribes into what was called “Indian Country” in Oklahoma.

As the 18th century turned into the 19th, the government programs of conquest and extermination grew more organized and more official. Chief among these initiatives was the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which called for the removal of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole Tribes from their territories in the Southeast.

Between 1830 and 1850, the government forced nearly 100,000 Native Americans off of their homelands. The dangerous journey to “Indian Territory” in present-day Oklahoma is referred to as the “Trail of Tears,” where thousands died of cold, hunger, and disease.

It’s not known exactly how many Native Americans died on the Trail of Tears, but of the Cherokee tribe of 16,000 some 4,000 died on the journey. With nearly 100,000 people in total making the journey, it’s safe to assume that the Native American death count from the removals was in the thousands.

Time and again, when white Americans wanted native land, they simply took it. The 1848 California gold rush, for example, brought 300,000 people to Northern California from the East Coast, South America, Europe, China, and elsewhere.

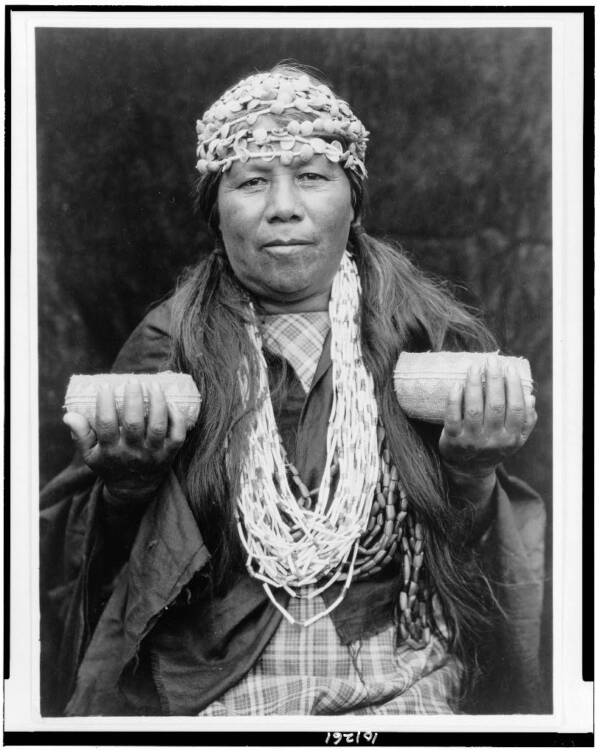

Library of CongressA female shaman from California’s Hupa tribe, photographed in 1923 by Edward S. Curtis.

Historians believe that California was once the most diversely populated area for Native Americans in U.S. territory; however, the gold rush had massive negative implications for Native American lives and livelihoods. Toxic chemicals and gravel ruined traditional native hunting and agricultural practices, resulting in starvation for many.

Additionally, miners often saw Native Americans as obstacles in their path that must be removed. Ed Allen, interpretive lead for Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park, reported that there were times when miners would kill up to 50 or more Natives in one day. Before the gold rush, about 150,000 Native Americans lived in California. 20 years later, only 30,000 remained.

The Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, passed on April 22, 1850, by the California Legislature, even allowed settlers to kidnap natives and use them as slaves, prohibited native peoples’ testimony against settlers, and facilitated the adoption or purchasing of native children, often to use as labor.

California’s first Governor Peter H. Burnett remarked at the time, “A war of extermination will continue to be waged between the two races until the Indian race becomes extinct.”

With more and more native people ripped from their homelands, the reservation system began — bringing with it a new era of the Native American genocide in which the Native American death toll continued to rise.

The Plight Of Native Americans In The Reservation Era

Wikimedia CommonsA settler in 1874 surrounded by the bodies of Crow people who were killed and scalped.

In 1851, the United States Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act which established the reservation system and set aside funds to move tribes onto designated lands to live as farmers. The act was not a measure of compromise, however, but rather an effort to keep Native Americans under control.

Native people weren’t even allowed to leave these early reservations without permission. As tribes accustomed to hunting and gathering were forced into an unfamiliar agrarian lifestyle, famine and starvation were commonplace.

Additionally, the reservations were small and crowded, with close-quarters allowing infectious diseases to run rampant causing countless Native American deaths.

On the reservations, people were encouraged to convert to Christianity, learn to read and write English, and wear non-native clothing — all efforts aimed at erasing their Indigenous cultures.

Then, in 1887 the Dawes Act divided reservations into plots that could be owned by individuals. This act was on the surface intended to assimilate native people into American concepts of personal ownership, but it only resulted in Native Americans holding even less of their land than before.

This harmful act wasn’t addressed until 1934 when the Indian Reorganization Act restored some surplus land to the tribes. This act also hoped to restore Native American culture by encouraging the tribes to govern themselves and offering funding for reservation infrastructure.

However, for countless tribes, this well-intentioned act came far too late. Millions had already been wiped out, and some Indigenous tribes are lost forever. It’s still not known for certain how many Native Americans were killed before it passed, or how many tribes were completely eliminated.

Discrimination Against Native Americans In The 20th Century

Carleton CollegeNavajo miners near Cove, Arizona, in 1952.

Unlike the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, which led to widespread legal reform, Native Americans gained civil rights piece by piece. In 1924, the U.S. Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act, which gave Native Americans a “dual citizenship,” meaning that they were citizens of both their sovereign native land and the United States.

Still, Native Americans did not gain full voting rights until 1965, and it wasn’t until 1968, when the Indian Civil Rights Act passed, that Native Americans gained the right to free speech, the right to a jury, and protection from unreasonable search and seizure.

However, the essential U.S. injustice against Native Americans — the taking and exploiting of their lands — has continued, simply in new forms.

Terry Eiler/EPA/NARA via Wikimedia CommonsNavajo man and woman in Coconino County, Arizona, among those documented by the Environmental Protection Agency over concerns about radiation starting in 1972.

As the Cold War nuclear arms race raged on between 1944 and 1986, the U.S. ravaged Navajo lands in the Southwest and extracted 30 million tons of uranium ore (a key ingredient in nuclear reactions). What’s more, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission hired Native Americans to work the mines, but disregarded the significant health risks that accompany exposure to radioactive materials.

For decades, data showed that mining led to severe health outcomes for Navajo workers and their families. Still, the government took no action. Finally, in 1990, Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act to make reparations. However, hundreds of abandoned mines still pose environmental and health risks to this day.

Native Americans Live In The Shadow Of Genocide Today

ROBYN BECK/AFP/Getty ImagesMembers of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and their supporters opposed to the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) confront bulldozers working on the new oil pipeline in an effort to make them stop, September 3, 2016, near Cannon Ball, North Dakota.

The long history of genocide perpetrated against Native Americans, as well as more recent memories of continuing exploitation and destruction of their lands, should help to explain why so many Native Americans have protested potentially dangerous development on or near their lands, such as the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Many Sioux tribal leaders and other indigenous activists said that the pipeline threatened the Tribe’s environmental and economic well-being, and would damage and destroy sites of great historic, religious, and cultural significance.

Protests at pipeline construction sites in North Dakota drew indigenous people from more than 400 different Native American and Canadian First Nations across North America and beyond, creating the largest gathering of Native American tribes in the last 100 years.

The Sioux also took their case to the courts. In 2016, under President Barack Obama, the Federal District Court in Washington heard their case and the Army Corps of Engineers announced that they would pursue a different route for the pipeline. However, four days into his presidency in 2017, Donald Trump signed an executive memorandum ordering the pipeline proceed as planned. By June, it was carrying oil.

Though the pipeline was ordered to shut down in 2020 when it became clear that proper environmental protections were not in place, it was a hard-fought victory for the Standing Rock Sioux. “This pipeline should have never been built here,” said Standing Rock Sioux Chairman Mike Faith “We told them that from the beginning.”

In 2020, Native American communities like the Navajo Nation have also had to contend with the Covid-19 pandemic. One in three Navajo families doesn’t have running water in their home, making it impossible to consistently wash hands or stay at home to prevent spreading the virus.

Additionally, only 12 healthcare centers and 13 grocery stores service the reservation which has a population of 173,000. As a result, the virus has been largely uncontrolled in the Navajo Nation, infecting more than 12,000 and killing nearly 600 people as of November.

Indeed, the Native American death count from Covid-19 has been staggering compared to the rest of the United States population as infection rates on reservations reach up to 14 times the rates outside.

At one point, Doctors Without Borders, an organization that typically operates in wartorn areas, deployed personnel to the Navajo Nation in an effort to quell the virus. And the Navajo are sadly far from the only tribe to suffer due to the pandemic.

More ominously, a Washington tribe that requested PPE and other supplies from the federal government mistakenly received a shipment of body bags in response. Though the government explained that the body bags were sent in error, the shipment horrified those who have not forgotten how many Native Americans were killed by Old World pathogens.

Ultimately, though some politicians are beginning to acknowledge the pain the Native American genocide caused, it seems that when it comes to U.S. policies against Native Americans, there is still much work to be done to right hundreds of years of wrongs.

After learning about the history of Native American genocide and how many Native Americans were killed, see these stunning portraits of Native Americans in the early 20th century. Then, discover the Osage murders, a greed-fueled conspiracy against Native Americans that led to the FBI’s first case.