Founded in present-day North Carolina in 1585 by Sir Walter Raleigh, the Roanoke Colony and its inhabitants vanished just two years later — and their fate remains unknown to this day.

The story of the Lost Roanoke Colony is one of history’s most famous mysteries for a reason. It has pirates, shipwrecks, skeletons, hoaxes, family drama, and an enduring question that has puzzled historians for 400 years… How did 117 people simply vanish?

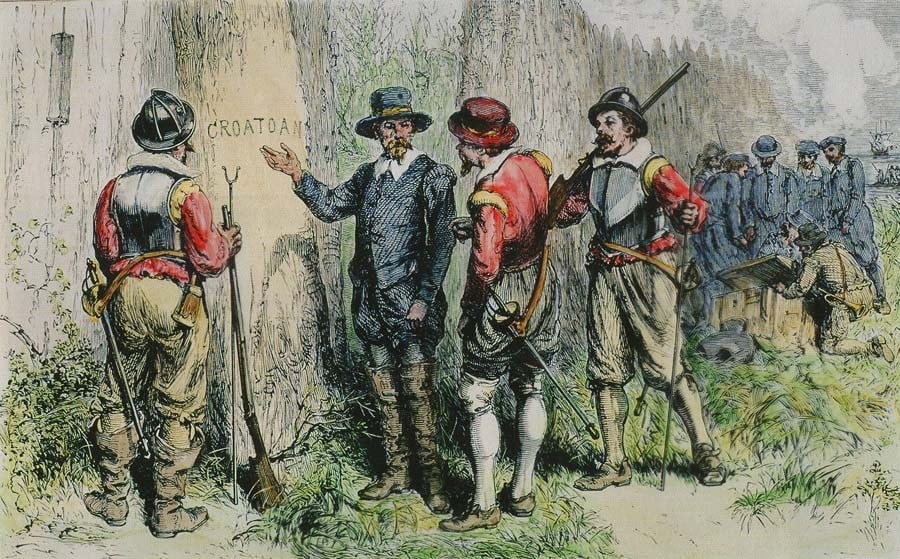

Wikimedia CommonsJohn White’s depiction of his 1590 expedition to Roanoke Island, when he discovered the lost colony missing. The word “Croatoan” was the only clue.

Just two years after Sir Walter Raleigh founded the Roanoke Colony for the English in present-day North Carolina, it was lost forever in August 1587 when all of its inhabitants disappeared at once. And though recent research has unearthed some tantalizing clues, the story of the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island remains shrouded in mystery to this day.

The Pre-History Of The Lost Roanoke Colony

The year is 1587. Under the rule of Queen Elizabeth I, England is strong and prosperous. Shakespeare writes in London’s taverns, Sir Francis Drake leads daring raids against the Spanish, and an increasingly literate and urban population turns its eyes to a new frontier: the Americas.

Among those attracted to the promise of the New World was John White, a gentleman artist and mapmaker with a passion for new lands. He had already been to North America once — though the experience was so harrowing that many were astonished he wanted to return.

Three years before the voyage of the famous Lost Colony of Roanoke, White had been the artist for the ill-fated 1585 expedition of Sir Ralph Lane, a mission so badly executed that it was a miracle anyone returned.

Wikimedia CommonsJohn White’s watercolors of the New World became famous back in England, especially depictions like this one of a ceremony being conducted by Secotan warriors. 1585.

White had been aboard the Tiger when it ran aground on a rocky North Carolina sandbar and destroyed most of its food supplies in the process.

Instead of making friends with the area’s well-provisioned natives, the mission’s admiral looted and burned an Algonquian village in search of a misplaced silver drinking cup he believed had been stolen.

The admiral then departed for other ventures, leaving Lane, White, and roughly 100 other men stationed on nearby Roanoke Island with the understanding he would return to resupply them shortly.

It was a disastrous move. The aggrieved Native Americans attacked the Roanoke settlement, and though the colonists managed to defend themselves, it was the final straw for many.

When Francis Drake miraculously showed up and offered them a ride home, a significant number took him up on the offer. The rest — all but a small detachment of 15 left behind to maintain England’s claim — hopped on the supply ships that appeared the following week and never looked back.

But White was different. Though he returned to England, he remained enthusiastic about the New World’s promise — so enthusiastic that when a second voyage to the area was proposed, he was asked to join, this time as the colony’s prospective governor.

And he didn’t just say yes. He convinced his own family, including his pregnant daughter and her husband, to join the perilous expedition along with 115 other hopefuls looking for adventure and a home in the New World.

The Early Days Of The Lost Colony Of Roanoke

Wikimedia CommonsJohn White’s depiction of the Native Americans he encountered around Roanoke. 1590.

It was a very different group that set out for North Carolina the second time around. The 1587 expedition, unlike the previous one, included women and children, and its members were more interested in settlement and a fresh start than exploration.

Like the 1585 colonists, however, they found themselves plagued with troubles almost from the moment their feet touched the ground.

For one, their new life was starting about 100 miles off course. Home was supposed to be a fertile site in the Chesapeake Bay area. But the ship’s navigator, forced to stop at Roanoke Island to check on the 15 men White’s last expedition had left behind, reportedly refused to continue on.

The colonists could stay at Roanoke, he said — it had been good enough for the last group, and he had Spanish ships to plunder.

So the colonists, eying their new home warily, forged inland to track down what was left of the old settlement.

The answer was unnerving: bones.

The 15 men from White’s original voyage had died in a coordinated attack by Native American warriors, leaving behind a wreck of an outpost and bad blood with the tribes of North Carolina.

It wasn’t an auspicious start, and the following weeks saw few improvements.

The beginnings of new relationships with the area’s Native Americans were blighted when White’s men conducted a dawn raid on the wrong tribe’s encampment, wounding friendly Indians who ended the day considerably less charitably disposed toward the Roanoke colonists.

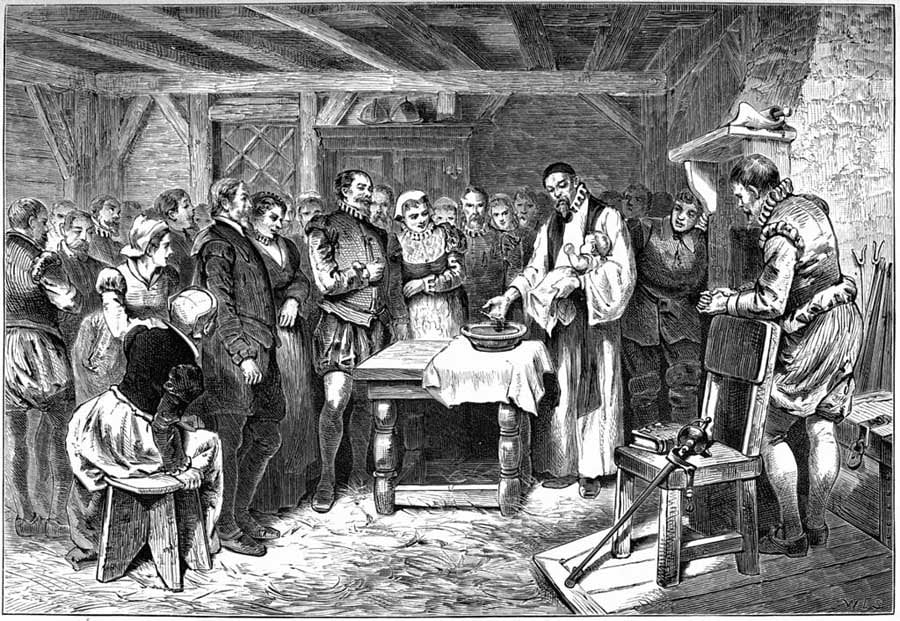

A brief ray of hope came with the birth of White’s granddaughter, Virginia Dare, who became in August the first English child born in the New World.

Wikimedia CommonsHenry Howe’s depiction of the baptism of Virginia Dare in the Roanoke Colony. 1587.

But the excitement of the moment faded as the colonists took a second look at their supplies, which were disappearing at an alarming rate. If things continued at their current pace, they were unlikely to survive the winter.

Worst of all, no help was coming. Few supply ships would stop at Roanoke Island, since there wasn’t supposed to be anyone there; the colonists had told everyone they were picking up the old group and heading for the Chesapeake.

They were also unlikely to be able to count on the Native Americans for aid, so badly had relations soured.

There was only one thing for it: John White would have to return to England to announce their relocation and return with supplies.

White was reluctant, and not just because he didn’t want to leave his daughter and young granddaughter.

Two fears warred in his mind: First, he didn’t want people back in England saying he was a coward for deserting his fledgling colony. Second, he didn’t want his belongings to be ruined in his absence.

Neither concern suggested White had a strong grasp of the gravity of the situation.

Eventually, the colonists were able to persuade the doubtful White that they would look after his things, and he sailed with the impatient navigator back to England, certain he would return with supplies before the first snows fell.

John White’s Return To The Lost Colony Of Roanoke

Wikimedia CommonsElizabeth I and the Spanish Armada, an unsigned painting depicting England’s 1588 naval war with Spain.

But John White didn’t return, not that winter, and not the next. He was gone for nearly three years.

It wasn’t his fault he couldn’t get back. When he arrived in England after a bad voyage, Queen Elizabeth I had just received intelligence that Spain had built an astonishing armada for one purpose: the invasion of England.

Knowing that she would be forced to meet the Spanish in battle on the seas, she banned English ships from leaving port; all vessels might be needed in the immediate future.

White was desperate, and after nearly a year of futile searching, he finally found two ships that were too small and ragged to be useful in England’s defense. He persuaded their captains to brave the Atlantic against their better judgment.

But the barely-seaworthy vessels never made it to Roanoke Island. They were attacked en route by French pirates, who took all the provisions meant for the Roanoke colonists. To add insult to injury, a beleaguered White was wounded in the “buttoke” during the skirmish.

Two years later, when the Spanish Armada was a wreck at the bottom of the ocean, White finally made it back to Roanoke.

He was very nearly a broken man. The voyage had once again been bad, with seven sailors lost in the landing at Roanoke alone. And he was plagued by the knowledge that he was very, very late.

He set foot on North Carolina soil on the very day his granddaughter had been born — three years ago. He had missed two birthdays, and he was hoping not to miss another.

Carol Highsmith/Library of CongressA scene from Lost Colony, an outdoor historical drama about the lost colony of Roanoke that has been playing for over 80 years in Manteo, North Carolina.

But when he arrived at the settlement, in an uncanny echo of the colonists’ discovery three years earlier, he found that not only was Virginia not there — nobody was.

The settlement was once more overgrown, and the houses had been stripped and demolished.

On a tree, White found the letters “C-R-O” carved painstakingly into the bark but apparently abandoned before the word could be completed. More illuminating was a carving on the old garrison post: “CROATOAN.”

At least there was no cross, White thought. He had told his family to add a Maltese cross to any message they left behind if they were departing under duress or in peril.

But of their whereabouts, there was no other sign. The only belongings in the old encampment were White’s own, destroyed by three years of exposure to the elements.

It was as if he was the only one who had ever been there — as if there had never been any settlement at all.

John White had lost the Colony of Roanoke.

What Happened To The Lost Colony Of Roanoke?

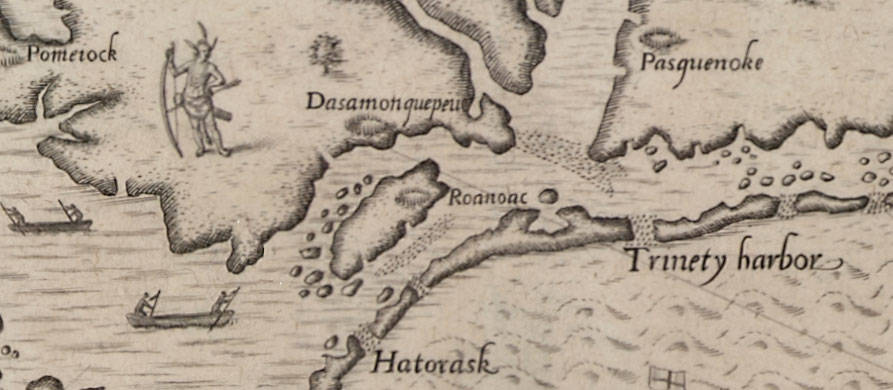

Wikimedia Commons“The Carte of All the Coast of Virginia,” an engraving by Theodor de Bry based on John White’s map of the coast of Virginia and North Carolina circa 1585–1586.

White would never know what happened to his family or the 115 men, women, and children he had left behind.

No one would.

But almost from the day they disappeared, the world has speculated.

Some say the colonists perished; after all, they were faced with nearly insurmountable odds going into the winter of 1587, and without White’s supplies, their chances of survival were slim.

But others point to the lack of bodies found on Roanoke Island and the clear evidence that the colony had been carefully dismantled. That, together with the messages carved into the tree and the post, presupposes a planned departure — albeit not one that made it particularly easy for anyone trying to track them down.

“Croatoan” was the original name of North Carolina’s Hatteras Island, and it was also the name of a tribe that made its home there.

Some speculate that the Roanoke Colony simply relocated there. This was what John White chose to believe, though he was prevented from investigating further as a brewing storm threatened to wreck the ship that had brought him back to Roanoke. It was leave or stay forever — and even if White had been willing to take the chance, his crew wasn’t.

Despite repeated pleas to the leaders of England’s seafaring community, White never made it back to the New World. But others did.

The 1607 Jamestown colony, a much more successful operation, asked friendly tribes about its unfortunate predecessor. John Smith, in conference with the chief Powhatan, was told that the Roanoke colonists had merged with a tribe that the Powhatans had killed in intertribal warfare; the colonists had been slaughtered.

Wikimedia CommonsDetail of John Smith from an illustration in The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles.

This news made it home to England in 1609 and for many years was the accepted history of the Lost Colony of Roanoke.

But modern historians aren’t convinced. Some believe John Smith misunderstood his conversation with Powhatan; the chief, they say, referred to the 15 original Roanoke colonists, not the 117 from the later colony.

Four hundred years of muddy history ensued. In the years immediately following the Roanoke disappearance, new colonists occasionally reported spotting Europeans living among tribal settlements — though their accounts were inconsistent.

Others found tribes with strangely European house-building techniques or, in later years, gray-eyed natives with a facility for English. Though at least one of these stories was revealed to be a sham, others are compelling, offering evidence of cohabitation with Europeans who seemingly predated the Jamestown settlers.

By the 1800s, a number of North Carolina tribes claimed descent from the Lost Colony of Roanoke — but with the passage of years, it has become nearly impossible to verify any claims.

Hoaxes And Theories About How The Roanoke Colony Vanished

Wikimedia CommonsA detail on John White’s map illustrating Roanoke Island.

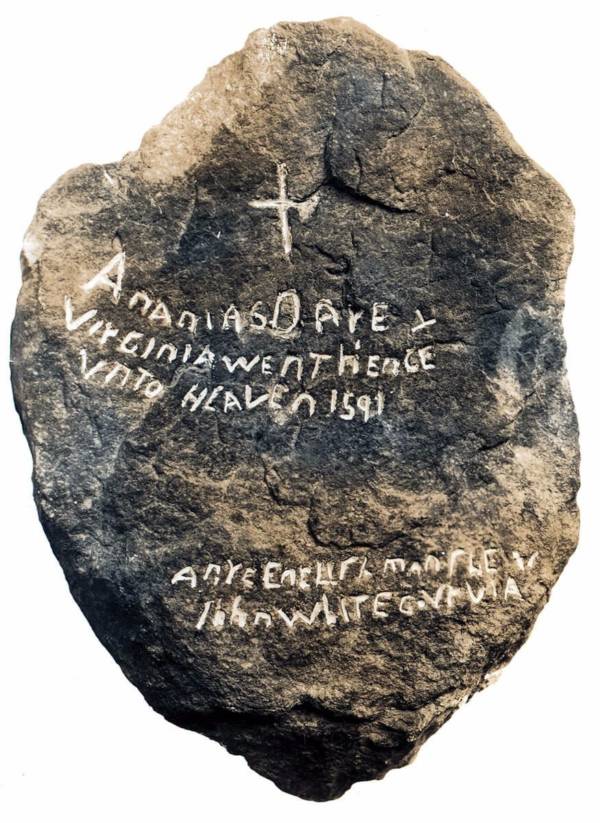

Then there are the hoaxes that have further confused the record, most famously the discovery of the Dare stones in 1937 by a tourist from California, who claimed to have found a rock bearing inscriptions by Eleanor Dare, John White’s daughter.

Then more people in the North Carolina–Virginia area produced a total of 47 more stones, which documented a complicated history: Eleanor and the colonists fled the area after a fatal clash with Native Americans, then found shelter with another tribe as far away as Georgia. Eleanor went on to marry a chief and die after giving birth to a daughter.

The stones initially sparked great interest in the archeological community, but a sharp-penned reporter pointed out that it didn’t make a lot of sense for someone to have carted nearly 50 stone messages that clocked in at 20 pounds each all the way from Atlanta to North Carolina.

Most damning of all, he further noted that all of the people who had found stones knew each other, and one of them was a stonemason who had recently suggested that visitors might pay to see the rocks that had at last solved the mystery of the Lost Colony of Roanoke. Another member of the group had a history of forging Native American artifacts.

The academics who had salivated over the rocks slunk away, and the issue was dropped until a recent study brought the Dare stones back into the public eye — or, more specifically, one of the Dare stones.

Alone of the set, the very first stone showed signs that it might not be a forgery at all. Though further examination is required, the debate has reignited, with the stone’s Elizabethan orthography at the center.

Wikimedia CommonsThe original Dare stone, allegedly from the lost colony of Roanoke.

If real, Eleanor’s inscription would suggest that 117 members of the Lost Colony of Roanoke moved inland, as they had indicated they might, where all but seven perished in Indian attacks and from sickness in the years after White left.

Among the dead were Virginia and Ananias Dare — meaning that John White led his family to their deaths in the New World, and neither he nor his granddaughter ever celebrated her third birthday.

Today, the search for truth continues. Excavations on Hatteras Island (once called Croatoan) have turned up intriguing artifacts but nothing that can be definitively attributed to the Roanoke colonists. Many suspect 400 years of shoreline erosion are to blame for the lack of evidence: what there was to find, they say, is now underwater.

The discovery of a mysterious patch on one of John White’s maps has offered new hope to archeologists, who believe the papered-over fort symbol, visible only when the map is placed over a light source, may indicate a secret, unexcavated encampment.

Others have gone a different route, searching for clues in the DNA of today’s population. They’ve invited people with Native American ancestry and those with surnames that match a Roanoke colonist’s to supply their DNA for genetic testing in an attempt to put the mystery to rest once and for all.

If their efforts prove successful, perhaps in time the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island will be found, bringing an end to John White’s 400-year-old search for the men and women who disappeared into the forests of the New World.

Enjoy this look at the Lost Roanoke Colony? For more of history’s most fascinating unsolved mysteries, read up on the Dyatlov pass incident, during which a group of hikers met a bizarre end. Then check out the strange story of the Sodder children, who vanished on Christmas Eve in 1945.