The right-hand man of Joan of Arc during the Hundred Years' War, Gilles de Rais is best known today as one of history's first documented serial killers.

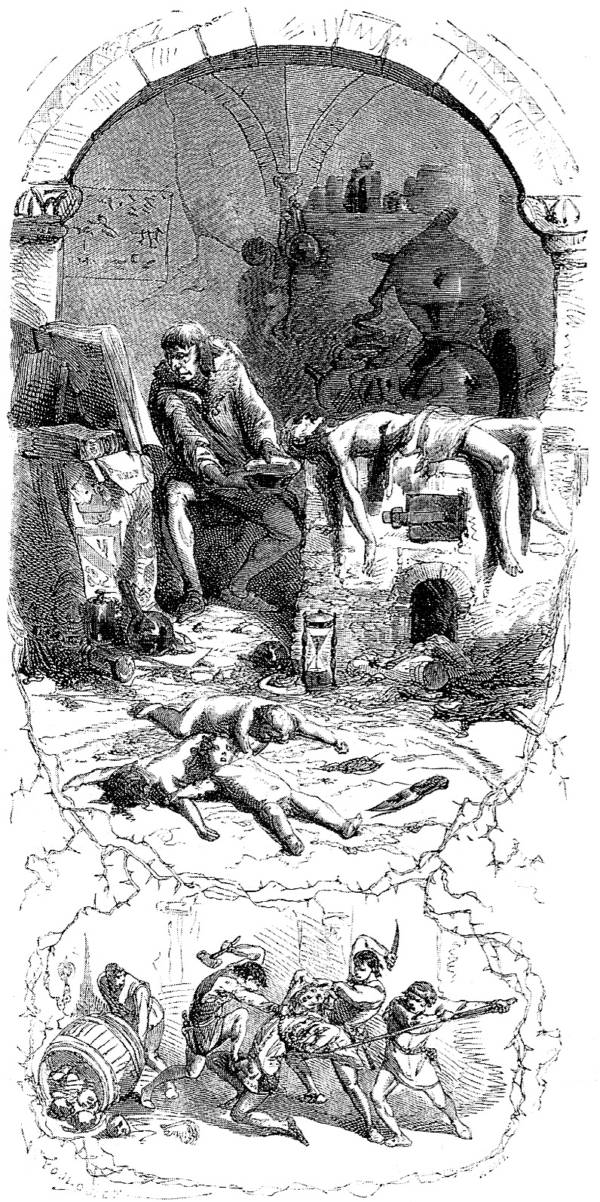

Stefano Bianchetti/Corbis/Getty ImagesGilles de Rais disposing of a corpse.

Gilles de Rais was an esteemed 15th-century nobleman and warrior. He spent much of his life defending France from England and fought bravely in the Hundred Years’ War alongside Joan of Arc. But Gilles de Rais is best known for murdering more than 100 children in dark occultist rituals.

His true nature wasn’t revealed until 1440. Then, during a shocking trial, de Rais was found guilty of heresy, sodomy, torture, and murder. His accusers alleged that de Rais had committed the gruesome crimes because of his interest in the occult, and his hope to summon demons.

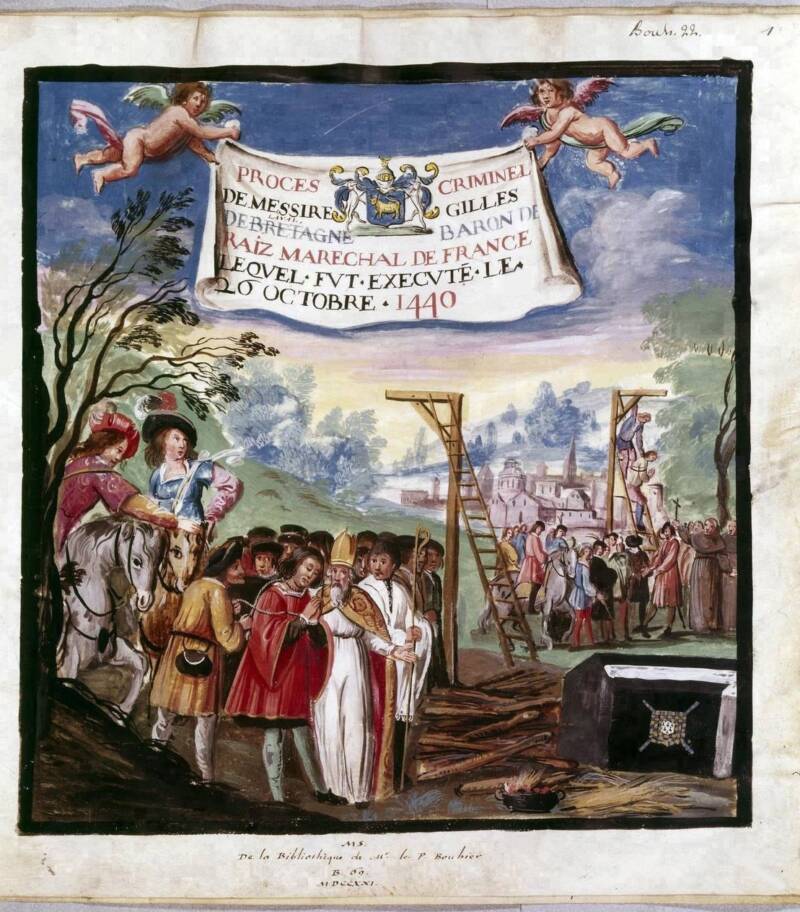

Sentenced to death, de Rais was hanged and burned, and his grisly story would go on to inspire the macabre legend of Bluebeard. But not everyone today believes that Gilles de Rais was guilty.

How Gilles De Rais Became A French Hero

Born Gilles de Montmorency-Laval in 1404 in Champtocé-sur-Loire, France, Gilles De Rais grew up in the lap of luxury. The son of wealthy nobles, he was a bright child who spent his youth studying Latin, reading and illustrating illuminated manuscripts, and learning about military strategy.

Wikimedia CommonsGilles de Rais in armor.

However, tragedy struck when de Rais was around 10 years old. Then, his father, Guy de Laval, was killed in a hunting accident which de Rais may have witnessed. Shortly thereafter, his mother, Marie de Craon, also died.

In the aftermath, de Rais was raised by his maternal grandfather, Jean de Craon. When de Craon’s son died during the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, he made Gilles de Rais his official heir, and arranged his marriage to the wealthy Catherine de Thouars.

This increased de Rais’ power and prestige. And when the Hundred Years’ War reignited in 1422 after a brief period of peace, Gilles de Rais leapt into the conflict — and became a national hero.

On the battlefield, de Rais was lauded for his bravery and determination. Then, in, 1429, he was tasked with accompanying Joan of Arc, a young Frenchwoman who claimed she had been instructed by angels to lead France to victory in the conflict.

The two fought bravely in several key battles, including at Orléans, as well as Jargeau and Patay. Joan of Arc became a national figure, and Gilles de Rais was given the high honor of being named Marshal of France, as well as a royal fleur-de-lis on his coat of arms.

Jean-Jacques Scherrer/Wikimedia CommonsAn 1887 painting of Joan of Arc liberating Orléans during the Siege of Orléans.

But in 1430, Joan of Arc was captured by the English. The next year, on May 30, 1431, she was burned to death in the city of Rouen.

Shortly thereafter, in 1435, Gilles de Rais ended his own military career and retreated to his estate. By then, he had allegedly been murdering children for two years.

The Dark Crimes Of Gilles De Rais

After Gilles de Rais retired from military service, his lifestyle grew decadent. He squandered his fortune on servants and his household, and through his patronage of the play Le Mistère du Siège d’Orléans (“Mystery Play of the Siege of Orléans”) on which de Rais spent the modern-day equivalent of millions of dollars. de Rais also became interested in the occult — and how he could use alchemy to regrow his fortune.

Wikimedia CommonsAn 1862 drawing depicting Gilles de Rais performing sorcery on his victims.

In this pursuit, Gilles de Rais purportedly started killing children. His crimes began in 1433, when he began to murder his victims at his childhood home of Champtocé. According to trial documents, most of his murders occured at his castle, Machecoul, where he sodomized his victims before bludgeoning them to death. Then, he decapitated their bodies and kept their severed heads on display — kissing his favorites from time to time.

He was allegedly encouraged by a cleric named Prelati. Alongside Prelati, de Rais would use blood and dismembered body parts from his victims to cast spells and try to summon demons.

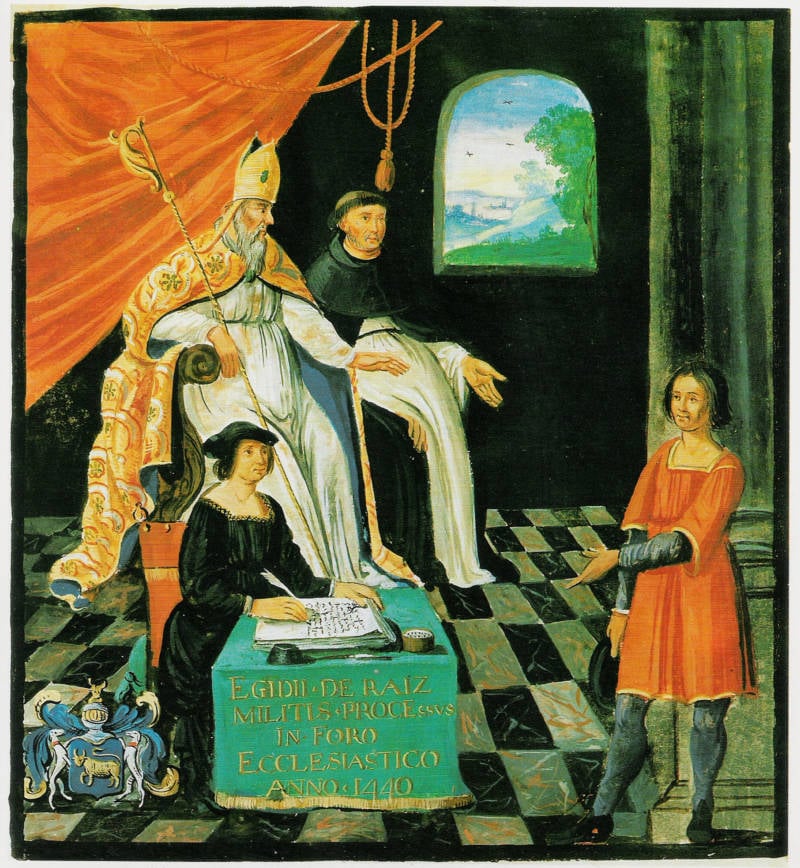

However, on May 15, 1440, de Rais and his men abducted a cleric from the Church of Saint-Étienne-de-Mer-Morte following a dispute. The Bishop of Nantes rapidly launched an investigation, which led church officials and lawmen to uncover evidence that de Rais had murdered 140 children.

When lawmen interviewed Gilles de Rais’ servants, they admitted to abducting children for him. The servants testified that he would masturbate on and molest the children before cutting off their heads. Two French clerics also testified de Rais engaged in alchemy and was obsessed with the dark arts — and that he used the limbs of victims for his rituals.

Wikimedia CommonsMiniature representing the trial of Gilles de Rais.

Several servants from neighboring villages also came forward to testify about children that had gone missing after begging near de Rais’ castle. In one instance, a furrier relayed how de Rais’ cousin had borrowed his 12-year-old apprentice, who was never seen again.

Under threat of torture, de Rais confessed to everything — murder, sodomy, hersey, torture, and necrophilia — on October 21, 1440. The disgraced nobleman told the court: “I have told you… enough to hang 10,000 men.”

He was ultimately found guilty and sentenced to die by hanging, with a fire lit beneath the gallows. Gilles de Rais was executed on Oct. 26, though his body was saved before the flames entirely reduced it to ash.

Centuries later, however, some believe that Gilles de Rais was not guilty at all — but the victim of a 15th-century witch hunt.

History’s First Serial Killer? Or An Innocent Man?

Though his guilt has been long accepted — Gilles de Rais even inspired the 1697 “Bluebeard” fairytale — some experts have come to question the official story. Historian Margot K. Juby, the author of The Martyrdom of Gilles de Rais, believes the threat of torture was so terrifying that de Rais confessed out of fear, or to save himself from excommunication.

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of Gilles de Rais’ execution.

“It seems impossibly quaint in the 21st century to read a text that fully accepts the validity of an Inquisition trial with the use of torture,” she remarked.

What’s more, the Duke of Brittany, who prosecuted the case that saw de Rais convicted, wound up receiving all the titles to de Rais’ lands after his execution. Some historians point to this as evidence of a political scheme.

And in 1992, a French writer named Gilbert Prouteau went as far as organizing a mock trial to investigate de Rais’ guilt.Comprised of French ministers, parliament members, and UNESCO experts, the court investigated all available evidence and came back with a verdict of not guilty. However, even Prouteau called the trial “an absolute joke” and it has no legal standing.

Ultimately, the truth of Gilles de Rais is impossible to know. Was he truly a vicious serial killer, one who murdered more than 100 children in his pursuit of the occult? Or was he a French war hero, unjustly accused and executed?

Centuries later, the truth is lost. But Gilles de Rais will certainly be remembered by history.

After learning about Gilles De Rais, the child serial killer who aided Joan of Arc, discover the strange and chilling story of the Beast of Gévaudan, the mysterious monster that terrorized villagers in 18th-century France. Then, read about Henri Landru, France’s modern Bluebeard serial killer.