1 of 42

Harlem became home to a large African-American population in a confluence of events: In the early 1900s, black churches began to move farther up town, bringing their congregations with them. A housing crash around the same time led real estate companies to bring in African-American families searching for cheaper housing and at the same time, over 400,000 black people migrated from the violently racist Jim Crow South to the more welcoming North.

Lenox Avenue in Harlem.Bettman Archive

2 of 42

In 1919, the highly decorated all African-American 369th Infantry Regiment returned to Harlem after World War 1. While they were treated as heroes in France, back home, African-American soldiers continued to be treated poorly. The lynching of Wilbur Little in Georgia, an African-American World War 1 veteran, served as the catalyst for the creation of the New Negro Movement. The movement was characterized not just by its most famous artistic outpouring, but by the first attempts at housing reform for poor black people living in tenements and the struggle to end employment discrimination,

The 369th Infantry Regiment parades through New York City

3 of 42

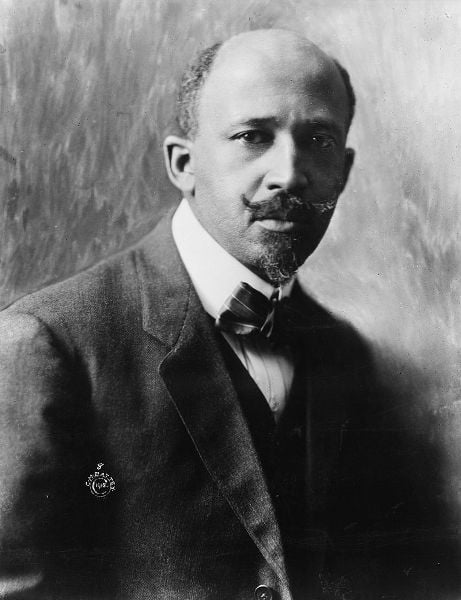

Author and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois inspired many of the artists central to the Harlem Renaissance, including Langston Hughes, who first came to prominence after being published in Du Bois' magazine The Crisis.

In addition, Du Bois also founded the Niagara Movement, a group of African-American intellectuals who protested racism, and later became a founding member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

While he established himself as a patron of the arts during the early years of the Harlem Renaissance, he soon separated himself from the artistic community, which he felt was not sufficiently using art to promote more important political causes.

W. E. B. Du Bois in 1918. Wikimedia Commons 4 of 42

In 1917, W.E.B. Du Bois and the NAACP organized the Silent Parade, in which more than 10,000 African-Americans protested lynching, and anti-black violence. The protest was meant to encourage then-President Woodrow Wilson to enact anti-lynching laws, which he failed to do. The parade was one of the first instances of all black demonstrations for civil rights. Wikimedia Commons

5 of 42

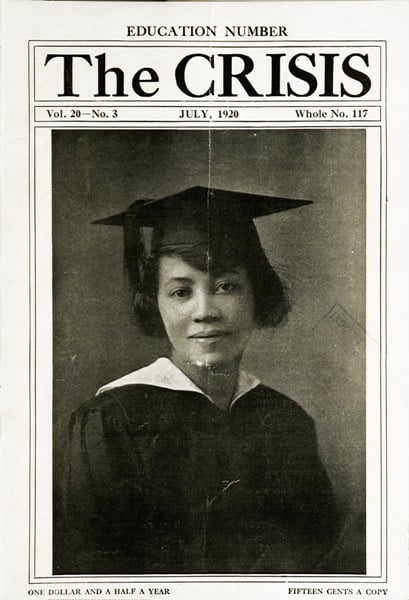

Under the editorship of W.E.B. Du Bois, The Crisis became the official magazine of the NAACP. Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Zora Neale Hurston all published within its pages. In addition to featuring prominent contemporary literary figures, the magazine also covered social justice issues, black cinema, higher education, and politics.

The August 1920 issue of The Crisis.Wikimedia Commons

6 of 42

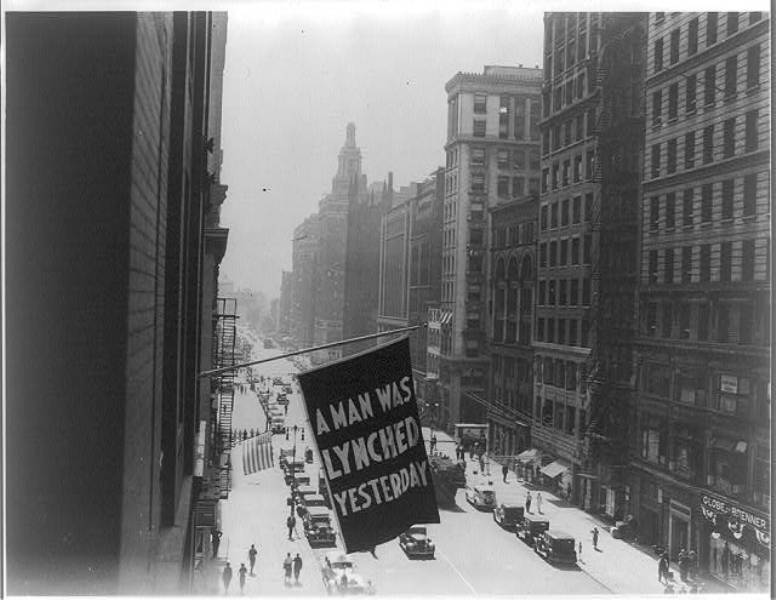

A flag announcing the lynching of an African-American man hangs out of the window of the NAACP headquarters at 69 Fifth Avenue. The practice of announcing lynchings began in 1920, but under threat of losing their lease, the NAACP was forced to stop in 1938.Library of Congress

7 of 42

Schoolboys in Harlem, 1930. Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

8 of 42

Jamaican-born civil rights activist Marcus Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association were instrumental in creating the atmosphere in which the arts could thrive in Harlem.

Garvey established the Negro World, one of the first newspapers to cover African-American arts and politics. The paper promoted emerging black writers and fostered a worldwide interest in the cultural movement taking place in Harlem.

Marcus Garvey in 1924. Wikimedia Commons

9 of 42

In 1920, UNIA organized a month of conferences, marches, and parades during what Garvey called the First International Convention of the Negro Peoples of the World. During the first convention, the UNIA adopted the Declaration of Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World, one of the first human rights declarations.Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

10 of 42

Marcus Garvey wanted to teach "Black ideals, black industry, black United States of Africa, and black religion" to his fellow African-Americans. More than 25,000 of his followers turned out for the first parade. Marchers in the UNIA parades carried this painting of the "Ethiopian Christ" as an example how they wanted to reincorporate their heritage into whitewashed histories. George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images

11 of 42

Even after Garvey was deported from the United States in 1927, UNIA continued to hold demonstrations like this one in 1930. Bettman Archive

12 of 42

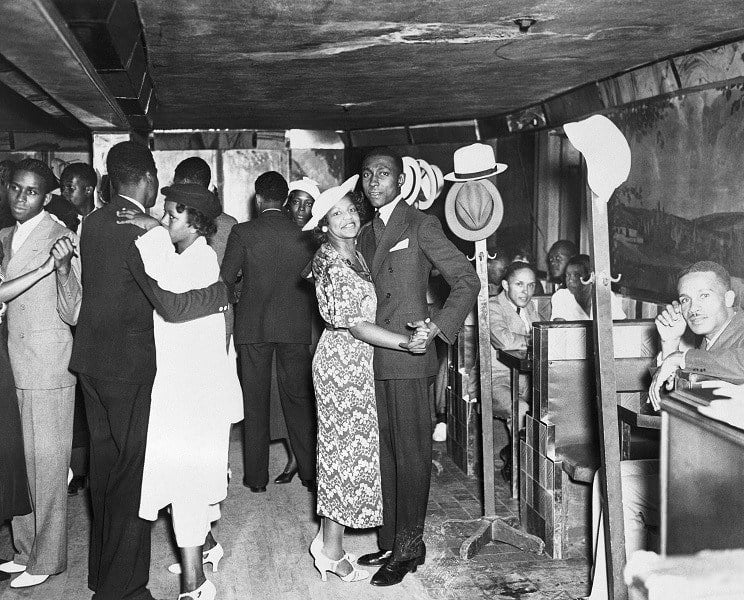

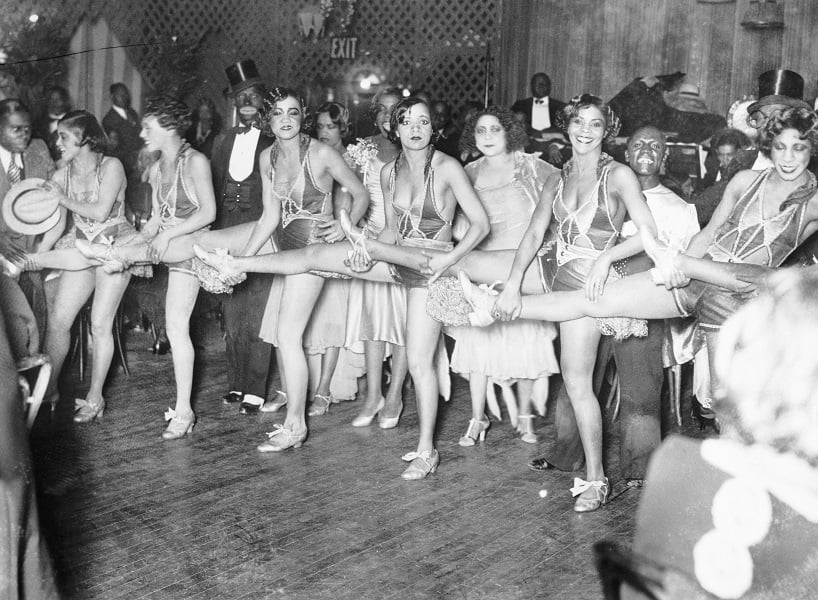

Night clubs were places of refuge for African-Americans during the Harlem Renaissance. These were the spaces where they could enjoy music and swing dance in a welcoming environment.Bettman Archive

13 of 42

Small's Paradise was one of the most popular jazz clubs of the era. Opened in 1925, the club was owned by an African-American man and welcomed both white and black customers, making it one of the only integrated clubs in Harlem. This club was known for popularizing the now iconic Charleston style of swing dance.

Small's Paradise Club in Harlem in 1929.Bettman Archive

14 of 42

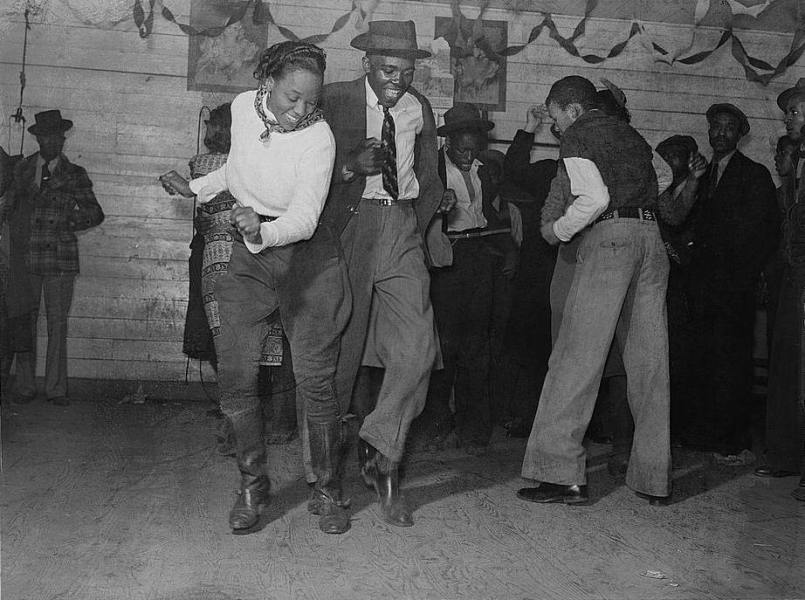

Though you may not know the name of dancer "Shorty" George Snowden, you've likely heard of his most famous creation: The Lindy Hop, the most well-known form of swing dancing.

Swing dancers at a club in Mississippi, 1939. Wikimedia Commons 15 of 42

Another popular spot was the Savoy Ballroom, where young men, decked out in the era's popular zoot suite, gathered to listen to jazz. The Savoy was also a well known for hosting some of Harlem's most talented Lindy Hoppers. Like Small's Paradise, the Savoy Ballroom allowed entry to all patrons, regardless of race or background. Writer Barbara Englebrecht called the Savoy the "soul of the neighborhood."Bettman Archive 16 of 42

Couples jitterbug at the Savoy Ballroom. Bettmana Archive

17 of 42

Though Harlem jazz hot spot The Cotton Club only admitted white patrons, its stage regularly featured the best African-American jazz musicians and singers of the time. The club showcased orchestras led by greats like Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington.

In light of this double standard, the poet Langston Hughes criticized The Cotton Club's racist policies, calling it "a Jim Crow club for gangsters and monied whites."

In 1935, the club closed after race riots broke out in Harlem, briefly moving to midtown, then closing for good in 1940.

Cab Calloway in 1947.Wikimedia Commons 18 of 42

An originator of big-band jazz, Duke Ellington was the band leader at the Cotton Club. Originally from Washington D.C., Ellington moved to New York as jazz became the dominant from of music during the Harlem Renaissance. His engagements at the Cotton Club landed the band a weekly radio program that spread the jazz craze throughout the country.

Duke Ellington at the Hurricane Ballroom. Wikimedia Commons

19 of 42

While Louis Armstrong went on to become one of the most famous and important musicians of the 20th century, he got his start largely out of the Harlem Renaissance.

Armstrong first gained recognition in New York playing at Connie's Inn in Harlem, one of Cotton Club's main business rivals.

Louis Armstrong in 1955. Wikimedia Commons

20 of 42

Jazz singer Ethel Waters rose from extreme poverty to become one of the most celebrated vocalists of the Harlem Renaissance.

All told, she recorded more than 50 hit songs during the 1930s, performed at the Cotton Club and Carnegie Hall, and in 1939, one critic called her the "finest actress of any race."

Ethel Waters in 1938. Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress 21 of 42

Nicknamed the "Empress of the Blues", singer Bessie Smith was one of the highest paid African-American entertainers of this era. In 1921, Harry Pace founded Black Swan Records and introduced singers like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey to the general public. Smith sold hundreds of thousands of records in the twenties and thirties, and worked with Ethel Water and Billie Holiday.Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress

22 of 42

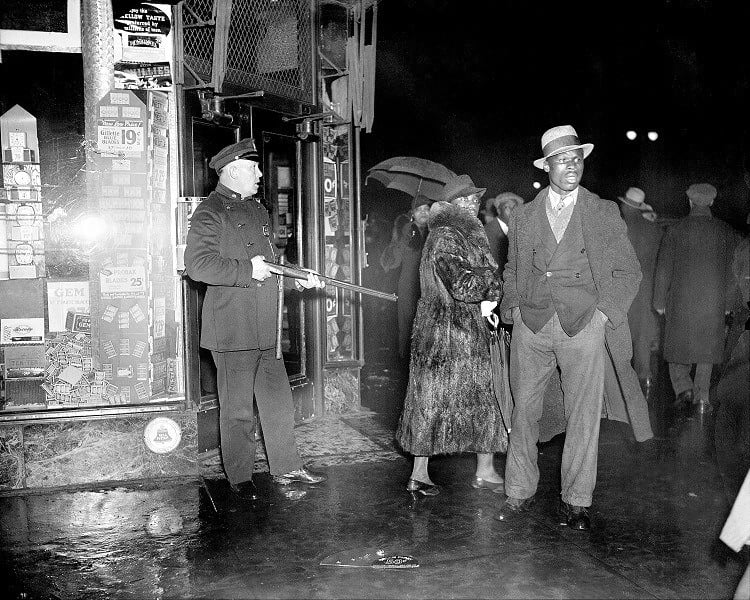

In 1930, a policeman shot and killed Gonzalo Gonzales on his way to a meeting for the Communist party. Just a few hours earlier, police beat Harlem resident Alfred Levy to death while in transit to a Communist party meeting. Communism had a strong foothold in African-American communities at this time, as the Communist Party helped organize labor unions that included white and black workers, and held multiracial protests against racism throughout the United States.Keystone-France\Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images 23 of 42

In 1935, Mussolini invaded Ethiopia in an effort to expand his facist empire. Harlem mobilized to fight the threat: Black men (nearly 8,000 from New York alone), trained for potential military service to combat the invading Italian forces. Anti-fascist Italians and African-Americans joined together for a march in Harlem to protest the invasion. By 1936, nearly 3,000 Americans had volunteered to fight fascism in Spain and Ethiopia.Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images 24 of 42

On March 19, 1935, a race riot broke out in Harlem. After a young Puerto Rican boy was stopped for stealing from a predominately white department store, police were called but the store owners decided not to press charges. Police led him away through the back exit of the store but when he disappeared with a cop, the gathered crowd assumed he would beat the boy. The rumors spread until people believed he had been killed by police, although no harm had come to him.NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

25 of 42

Though this incident sparked the riot, Harlem had reached a boiling point dealing with increasingly difficult living conditions. Harlem residents had long been feeling resentment over police brutality and an unemployment crisis in the neighborhood -- around 50% of people in living were out of work. Though the riots only lasted one day, three people were killed, hundreds more injured and looting and destruction of property caused $200 million dollars in damages.

Police arrest two looters during the riots, 1935. Bettman Archive

26 of 42

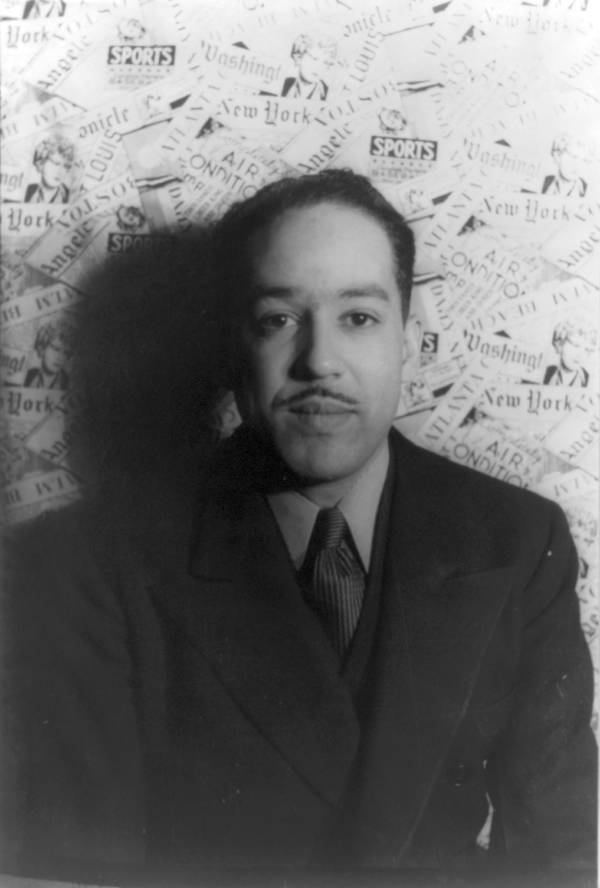

Langston Hughes is arguably the most prominent figure of the Harlem Renaissance. His writing focused on the experiences of working class African-Americans, both protesting racism and celebrating the black identity in its diverse forms.

Known for experimenting structurally in his work, Hughes often incorporated jazz rhythms into his poems. He was, according to some, the first African-American artist to earn a living exclusively from writing.

Langston Hughes in 1943. Wikimedia Commons 27 of 42

In 1922, philanthropist William E. Harmon established the Harmon Foundation, which would become one of the largest patrons of African-American artists during the Harlem Renaissance. William E. Harmon Foundation Award for Distinguished Achievement Among Negroes recognized exceptional artistic talent among otherwise unrecognized black artists and was awarded to Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen among others.

Langston Hughes with Charles S. Johnson, E. Franklin Frazier, Rudolph Fisher, and Hubert T. Delaney at a party for Hughes in 1924.New York Public Library

28 of 42

Zora Neale Hurston was one of the most influential writers of the Harlem Renaissance.

When Hurston arrived in New York to attend Barnard in 1925, the Harlem Renaissance was in full swing and she quickly became one of the writers at the center of the movement. Beyond her acclaimed novels, Hurston also published works of folklore and literary anthropology of the African culture and traditions.

Zora Neale Hurston between 1935 and 1943. Wikimedia Commons

29 of 42

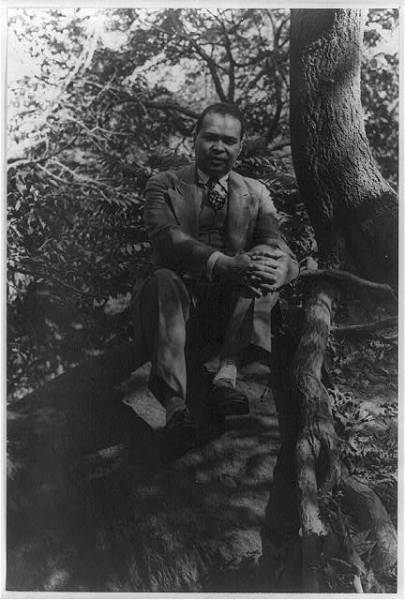

Countee Cullen used poetry to reclaim African art in a movement called "Négritude," which was central to the Harlem Renaissance.

However, Cullen hoped that African-American writers would draw their influences from the European poetry tradition. This is in part because, according to the Poetry Foundation, Cullen hoped for a "color blind" world.

Countee Cullen in Central Park, 1941.Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress 30 of 42

Dunbar Bank, funded by the powerful Rockefeller family, served Harlem as the only bank in the area that employed African-Americans. Though it closed in the 1930s, the bank was the first of it's kind, established specifically for Harlem's black residents. Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images 31 of 42

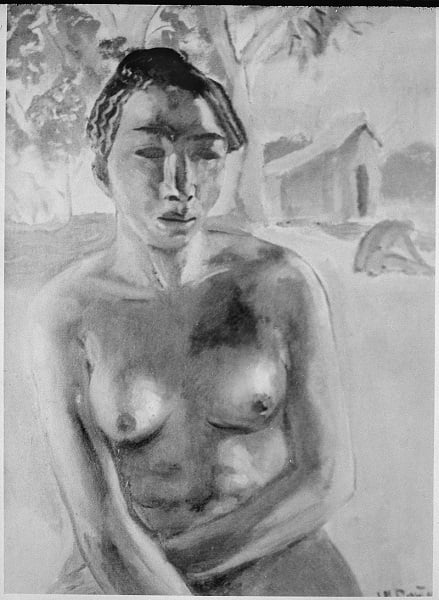

Painter James Porter was the driving force behind creating the field of African-American art history studies. During the Harlem Renaissance, he attended the Art Institute. At the tail end of the movement, he published Modern Negro Art, the first comprehensive study of African-American art in the United States.

African Nude by Palmer Hayden, 1930.

32 of 42

Painter Palmer Hayden called The Janitor Who Paints "a sort of protest painting" of the economic and social situation of African-Americans in the 1930s. Much like this important, evocative piece of work, the bulk of Hayden's output depicts daily life in Harlem during the renaissance.

The Janitor Who Paints by Palmer Hayden, 1930. Palmer Hayden 33 of 42

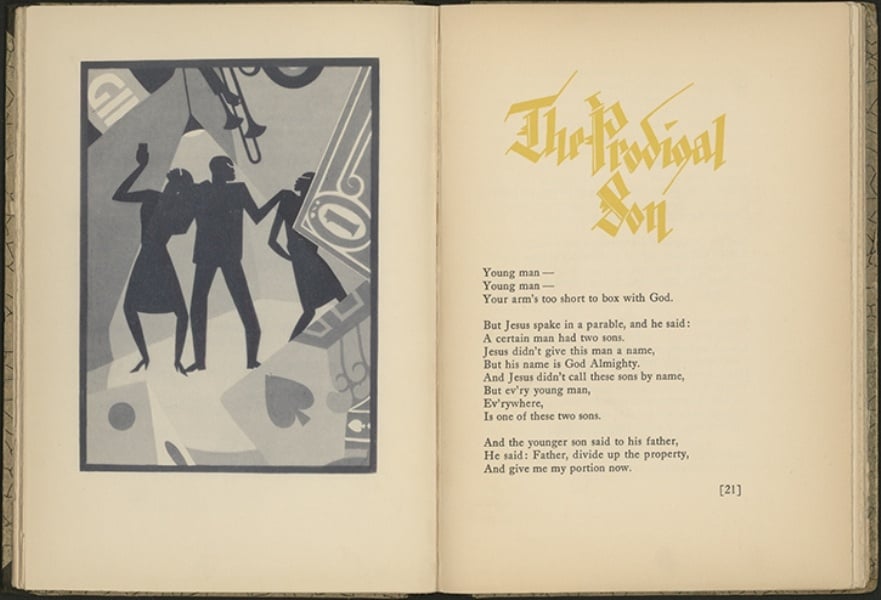

Another one of the main architects of the Harlem Renaissance was writer and activist James Weldon Johnson, who believed that African-Americans would only experience true artistic achievement when they became equal in society.

Johnson joined up with illustrator Aaron Douglas -- who also produced work for Du Bois' magazine, The Crisis and was considered the "Father of African-American arts" -- to create God's Trombones, a poetry book made in tribute to the “old time Negro preacher,” according the Library of Congress.

A page from God's Trombones.Library of Congress 34 of 42

Photographer James Van Der Zee captured middle class life in Harlem in the 1920s and 1930s. In fact, his studio operated for 50 years, capturing funerals, weddings, and even celebrities like the dancer Bill "Bojangles" Robinson.

As historian Sharon Patton put it, Van Der Zee "helped create the period, not merely document it."

Couple with a Cadillac, Harlem; 1932. James Van Der Zee/YouTube 35 of 42

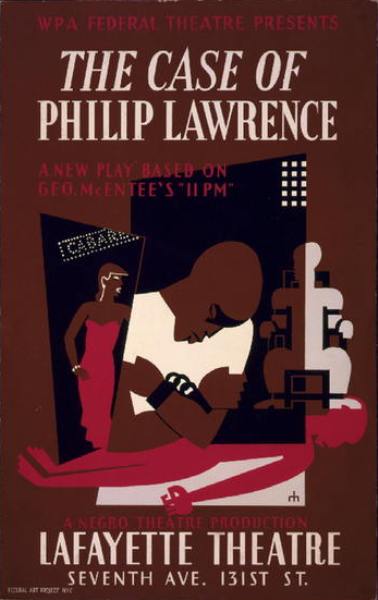

With help from the government-funded Negro Theatre Unit -- part of The Federal Theatre Project, a New Deal program -- stage productions flourished during the Harlem Renaissance.

Based at the Lafayette Theatre in Harlem, the Negro Theatre Unit put on more than 30 different plays during this era.

Playbill for the Negro Theatre Unit's production of The Case of Philip Lawrence, 1937. Library of Congress

36 of 42

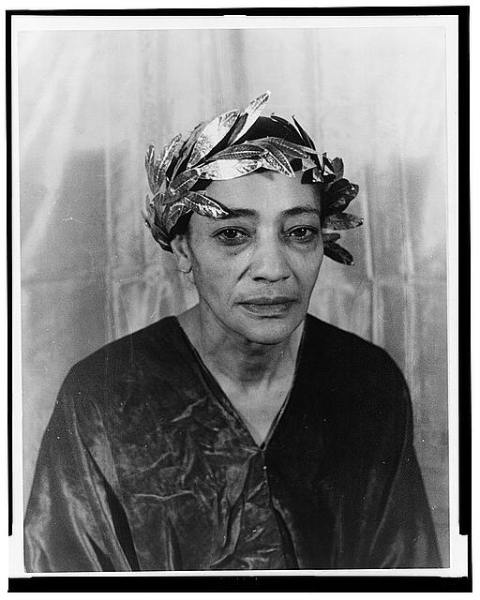

Actress Rose McClendon was instrumental in bringing the Negro Theatre Unit to life. She then went on to help create versions of this project in other cities across the country.

Rose McClendon in 1935.Carl Van Vechten/Library of Congress

37 of 42

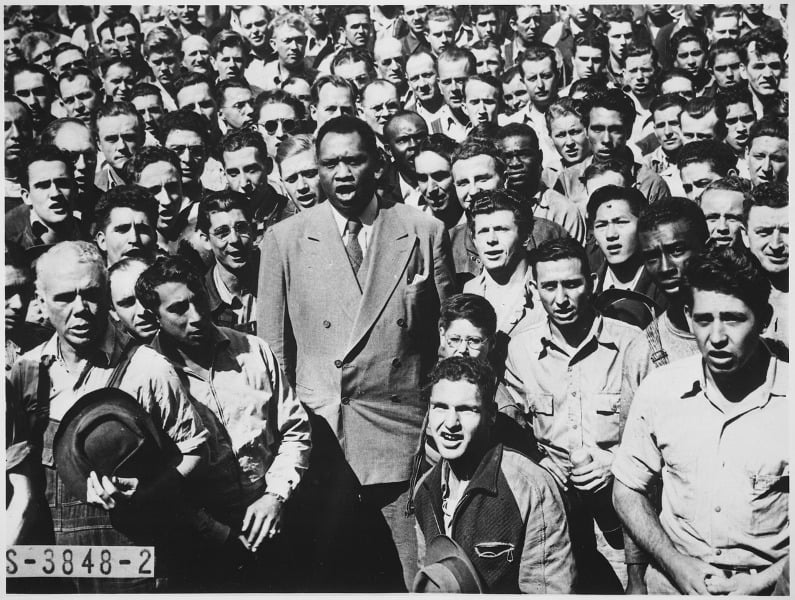

As one of the most black famous actors of the 20th century, Paul Robeson owed his fame to the Harlem Renaissance.

Robeson initially practiced law in New York, but he was so disgusted by the racism that he faced in that profession that he quit to pursue acting full time. He first gained notoriety when he starred in Eugene O'Neill's All God's Chillun Got Wings (which featured a controversial interracial romance), and then continued to break ground by claiming roles usually reserved for white actors.

The more Robeson acted, the more passionate he became about civil rights as well and his movement towards communism caused him to be blacklisted in the 1950s.

Paul Robeson leading shipyard workers in the "The Star-Spangled Banner," 1942. Wikimedia Commons

38 of 42

Paul Robeson starring in the 1943 production of Othello.Wikimedia Commons

39 of 42

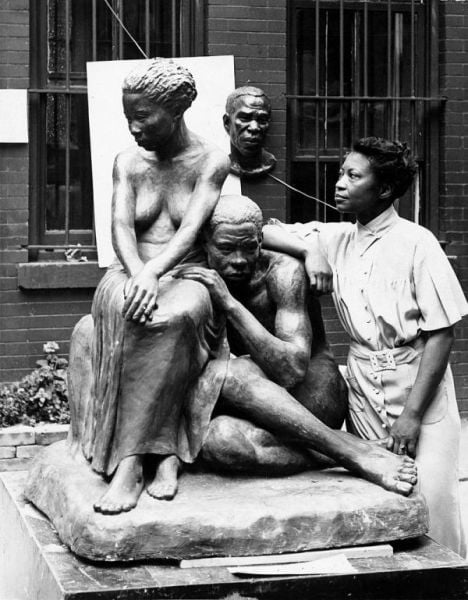

Though the sculptor Augusta Savage started her career in Europe, she returned to the United States in the early 1930s, and in 1934, she became the first black women admitted to the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors.

She then founded the Savage School of Arts, which provided a wide range of free art classes open to the public. Toward the end of the Harlem Renaissance, Savage opened the first gallery to sell and exhibit art by African-Americans in Harlem, called the Salon of Contemporary Negro Art.

Augusta Savage in 1938.Wikimedia Commons

40 of 42

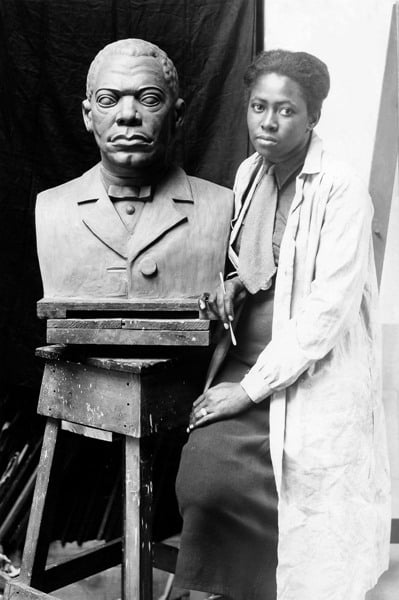

In addition to Augusta Savage, the Harlem Renaissance produced another great female sculptor in Selma Burke. Burke originally worked as a nurse in Harlem but the flowering artistic community in the neighborhood inspired her to pursue her true passion.

Although her subjects were often prominent members of the African-American community like Booker T. Washington and Duke Ellington, she's best known for her bust of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In 1946, after having completed many noteworthy works, she founded the Selma Burke Art School in New York so that others could follow in her footsteps.

Selma Burke with her bust of Booker T. Washington in 1935.Wikimedia Commons

41 of 42

Langston Hughes himself specified that the official end of the Harlem Renaissance coincided with the end of Jazz Age, after the stock market crash of 1929 signaled the beginning of the Great Depression. However, the impact of the movement allowed black artists like Augusta Savage, Palmer Hayden, and Countee Cullen, to thrive and Harlem remained a focal point of black culture for decades after.Wikimedia Commons

42 of 42

Like this gallery?

Share it: