No, so-called "patient zero" Gaetan Dugas didn't introduce HIV/AIDS to the United States.

The 1980s AIDS crisis was one of the most profound epidemics not just in the United States, but in all of human history.

Now, a new study has revealed what many of us didn’t know about the epidemic: Namely that scientists misidentified “patient zero,” or the person believed to be the first case on U.S. soil — due to a filing system typo. In attempting to ascertain how HIV/AIDS arrived in the U.S., scientists’ work has firmly and finally exonerated the man long believed to be the first case, more than 30 years after the fact.

AIDS In The U.S.

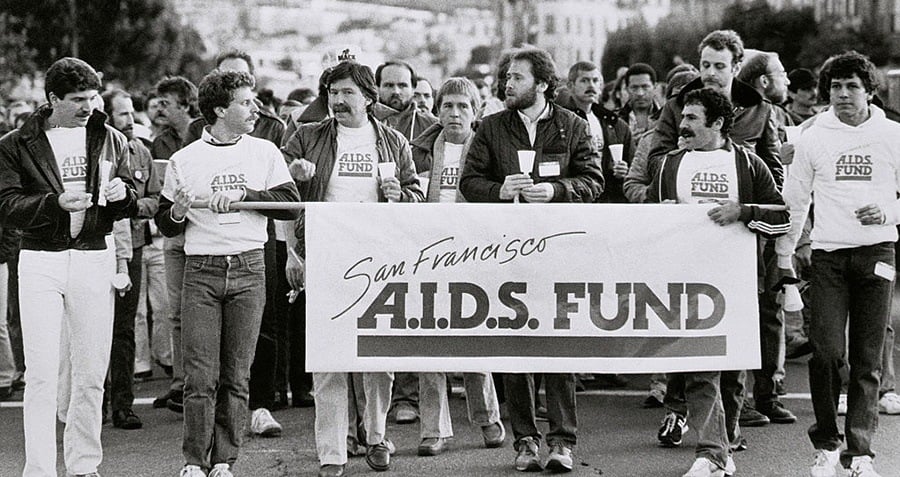

Getty ImagesNearly 2,000 people participate in San Francisco’s annual candlelight parade honoring local hero Harvey Milk, gay and lesbian pride, and social concerns related AIDS.

Prior to 1980, HIV/AIDS was a relatively unknown virus in the U.S. Case reports circulated sporadically around the world, but expert consensus held that the disease had only begun to spread from chimpanzees to humans sometime in the 1920s.

At the dawn of the 1980s, when a mysterious respiratory virus began to take hold of previous healthy young men in Los Angeles, doctors began to look for patterns among the infected.

They found that the virus tended to strike gay men, and that on the East Coast, young gay men with similar symptoms had developed an aggressive cancer called Kaposi’s Sarcoma. By the end of 1981, doctors had also seen the virus in intravenous drug users, which served as another important clue. That year saw 270 reported cases, and 121 of the patients died.

Over the next few years, the syndrome caused by the as-yet unidentified virus became colloquially known as “gay-related immune deficiency,” but researchers began referring to it as acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

By 1983, medical scientists had identified the first female AIDS patients and the transmission of the virus started to become more clear. More importantly, researchers established that the virus did not confine itself to gay men. It could be, and was indeed being, passed through heterosexual intercourse.

Throughout the rest of the decade, researchers not only identified HIV/AIDS as a disease, but began to formulate life-saving treatments for it. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) established protocols, recommendations, and procedures that helped prevent further spread of the disease, such as education about safe sex and the risks of sharing needles.

The question that remained, however, was how the virus had arrived in the U.S. in the first place.

Who Is Patient Zero?

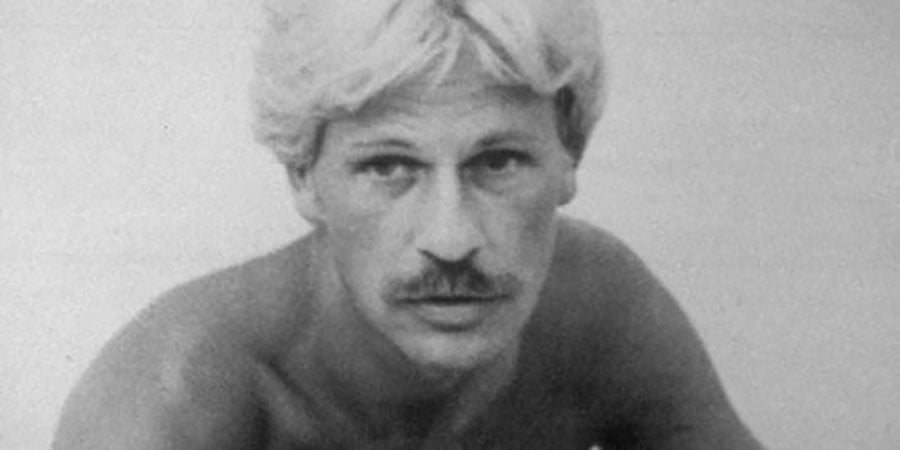

Le MondeGaetan Dugas.

Epidemiologists, those who study diseases on a population scale, often try to work backwards to identify the first case in an outbreak, so that they can find the source. This is especially true in cases of food-borne illness, where illness in many people originated from a single food or food-producing location.

In the case of HIV/AIDS, working backwards to find “patient zero” has been part of the history of AIDS in the U.S. for the last 30 years. And conventional wisdom has long held that researchers had indeed found that patient. But new research now indicates that that finding was incorrect, and that a mere labeling error was the cause.

For the last several decades, the story went that a French-Canadian flight attendant named Gaetan Dugas first brought HIV to the U.S. Numerous books and films have chronicled his story — and of course stigmatized him — but it turns out that he was never patient zero at all.

Indeed, a study published in the journal Nature earlier this week shows that Dugas’ file was just one amid hundreds of thousands of AIDS patients, and that CDC researchers had labeled it with the letter “O,” not a “0.”

Researchers used the letter “O” to indicate that the patient was from “outside of California.” At the time, the bulk of known cases were in California (particularly San Fransisco), and that’s where CDC researchers focused their efforts.

Those investigating the outbreak had never actually suggested that Dugas was the source, but because of the vague label on his file and the public’s desire for answers during a time of terrible fear, Dugas’ story became well-known — particularly through journalist Randy Shilts’ famous 1987 novel And The Band Played On, which presents Dugas as a globetrotting sexual deviant whose feckless behavior introduced AIDS to the U.S.

Years later, Shilts’ former editor would reveal that she felt the chronicle needed a literary device and as such she encouraged Shilts to create the first “AIDS monster,” a role Shilts gave to Dugas.

Of course, Dugas was not an “AIDS monster;” rather, he fell victim to fear and bungled bureaucracy.

A Revised History

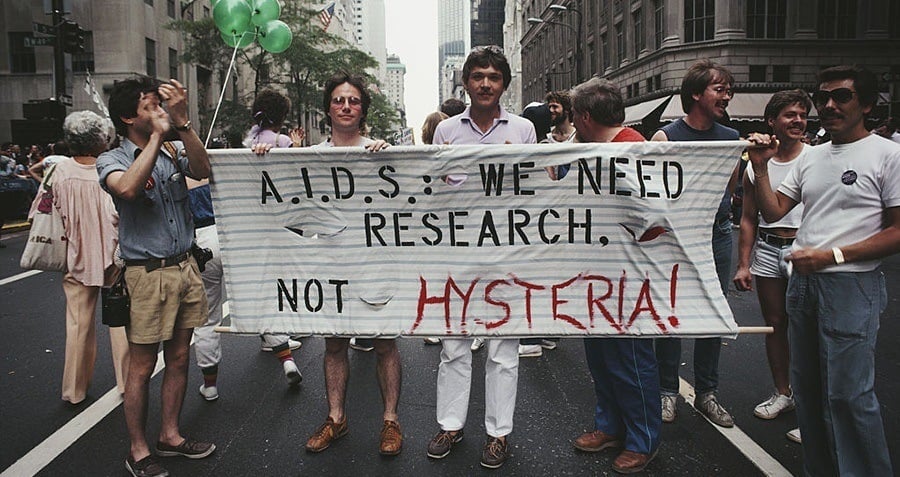

Barbara Alper/Getty ImagesGay pride parade marchers move through Manhattan carrying a banner that reads “A.I.D.S.: We need research, not hysteria!,” June 1983.

New research retested some of the first patients’ DNA for HIV antibodies — even those patients whose samples were taken before HIV was a known quantity. Essentially, researchers found that there were many people contemporary to Dugas — in Californa, New York City, and elsewhere — who had HIV antibodies at the same time that he did. There was nothing to suggest that Dugas had the virus before anyone else.

In fact, based on these samples, it appears that the virus arrived in the U.S., most likely from Haiti, sometime in 1971, but lived “under the radar” for at least a decade. Researchers believe that the epidemic most likely began in New York City, then came to San Fransisco’s gay community sometime in the early ’80s, where it proliferated quickly.

Although the findings have been published and Dugas’ name has been cleared once and for all, the man himself will never know. Dugas died of AIDS in 1984.

Next, see the photograph that changed the way Americans viewed AIDS. Then, read even more about the surprising origins of HIV.