How Mikhail Kalashnikov invented the AK-47, why it took over the world, and what he wishes he'd made instead.

NATALIA KOLESNIKOVA/AFP/Getty ImagesMikhail Kalashnikov, the Russian inventor of the globally popular AK-47 assault rifle.

In April 2013, an ailing Mikhail Kalashnikov wrote a letter addressed to the head of the Russian Orthodox Church. According to Russian daily Izvestia, Kalashnikov posed the following question in his missive: If his own invention “deprived people of life, then can it be that I… a Christian and an Orthodox believer, was to blame for their deaths?”

Mikhail Kalashnikov would die several months later. As his surname would imply, his invention was the Kalashnikov assault rifle, the AK-47.

Mikhail Kalashnikov’s Early Days

From start to finish, the life of Mikhail Kalashnikov is the stuff of Soviet “peasant-brings-glory-to-Mother-Russia” legend.

In November 1919, Kalashnikov was born to a poor family in Kurya, Siberia. He was a sickly child who enjoyed poetry, and who in 1930 saw his parents’ property seized by the state during the Soviet collectivization process. In 1932, Joseph Stalin, then leader of the Soviet Union, forced Kalashnikov’s family into a penal colony elsewhere in Siberia, where his father died during their first winter there.

At about 13, Kalashnikov abandoned his family and headed back to Kurya — some 600 miles away. There, he found work at a tractor station, where he began to develop an interest in and love for machinery.

Soon enough, Kalashnikov joined the Red Army to aid in its fight against the Nazis on the Eastern Front. Due to his slight size and background in engineering, Kalashnikov would first work as a tank mechanic. A few years and promotions later, Kalashnikov would come to serve as a tank commander.

It was during the war that Kalashnikov says his idea for the AK-47 took flight. While commanding a T-38 tank in 1941, German shrapnel injured Kalashnikov and landed him in the hospital, where he encountered a patient who would change the course of Kalashnikov’s life — and, if Kalashnikov’s story is to be believed, warfare as we know it.

“I was in the hospital, and a soldier in the bed beside me asked: ‘Why do our soldiers have only one rifle for two or three of our men, when the Germans have automatics?'” Kalashnikov told the Independent. “So I designed one. I was a soldier, and I created a machine gun for a soldier. It was called an Avtomat Kalashnikova, the automatic weapon of Kalashnikov—AK—and it carried the date of its first manufacture, 1947.”

The Birth of the AK

Oleg Nikishin/Getty ImagesMikhail Kalashnikov celebrates the 55th anniversary of the AK-47 in Moscow in 2002.

While some have since questioned the veracity of this founding myth as told by Mikhail Kalashnikov — instead saying that a couple supervisors altered his AK model during trials and it thus wasn’t truly his — the general story goes this way:

Feeling the heat from the Germans’ use of the Sturmgewehr 44 assault rifle, in 1943 the Soviet Union endeavored to create an automatic weapon of their own that could compete with it. Soviets soon developed cartridges for this weapon, and sent some to Kalashnikov, telling him they were meant for new weapons and could “lead to greater things.”

Kalashnikov, whom at this point had gone to engineering school and received patents for some of his firearm designs, got to work on developing this weapon. Aided by some healthy competition (multiple designers competed against one another to develop weapons for Soviet use) and failures which forced him to work harder on his craft, Kalashnikov eventually created a light, small arms rifle and sent it off for the Kremlin’s consideration in 1946.

Lighter and more durable than the Sudayev, a Soviet favorite, the Kremlin sent its seal of approval to Kalashnikov, and advised him to produce a prototype. Kalashnikov then assembled a team of workers to do so, and his prototype, the AK-47, passed troop trials with very few difficulties.

In 1949, the Soviets adopted Kalashnikov’s design, praising it for its ease of use and reliability. It underwent a few alterations — critically, reducing its weight — and became the A.K.M., a weapon which would help shape the course of events during the Vietnam War.

How the AK Changed Warfare

Getty ImagesA Vietnamese soldier with an AK.

Newly-minted assault rifle in tow, the Soviets began supplying their allies with AKs, including the guerrillas in North Vietnam and the Viet Cong in the South. Americans, then using the M-16 in their wars abroad, dismissed the AK, saying that it was cheap and “lacked range and stopping power.”

Future events in Vietnam would give the U.S. reason to rue such a dismissal: Where the M-16 experienced corrosion and jamming, the deadly simple, 600-plus-rounds-per-minute AK saw no problems, packed enough bullets such that its user could continue firing well after his opponents ran out of ammunition, and could endure just about any environment in which it landed.

The M-16 fared far worse in Vietnam’s wet, humid environs, jamming so much that American soldiers in Vietnam began picking up AKs that belonged to deceased Vietnamese soldiers and using them instead of the M-16. As Esquire magazine recounted at the time, on one occasion a US sergeant carrying an AK-47 was stopped by his commander, who demanded to know why he had a Russian weapon. The sergeant replied, “Because it works!”

The AK did work — so much so that it became part and parcel of armed revolts around the world. Indeed, soldiers used the AK in Palestinian, Angolan, Algerian, and Afghan revolutions, and the weapon soon found itself embedded within flags and coats of arms in newly-independent countries like Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Burkina Faso, and East Timor.

Wikimedia CommonsThe flag of Mozambique.

Mikhail Kalashnikov and his gun had become the stuff of legend. And according to Kalashnikov, the rifle’s users were quick to say so.

“When I met the Mozambique minister of defense, he presented me with his country’s national banner, which carries the image of a Kalashnikov submachine gun,” Kalashnikov said in a 2001 interview. “And he told me that when all the liberation soldiers went home to their villages, they named their sons ‘Kalash.’ I think this is an honor, not just a military success. It’s a success in life when people are named after me, after Mikhail Kalashnikov.”

The Weapon’s Global Downsides

David Silverman/Getty ImagesA Palestinian boy holds a gunman’s AK-47 assault rifle during a round of fighting with Israeli soldiers on October 26, 2001.

Still, the AK did not exclusively serve as an instrument of liberation. As Nigel Fountain wrote in his review of Michael Hodges’ AK47: The Story of the People’s Gun, “With 650 rounds pumped out a minute, Kalashnikov’s cheap and cheerless, charismatic assembly of tube and wood has, with added global trickle-down, put mass slaughter inside the budgets of ordinary Joes — and Abdullahs and Reiks — everywhere.”

Indeed, Hodges notes that as many as 200 million AK-47s exist around the world — around one gun per 35 people. Given the rifle’s extreme accuracy and reliability, it remains a hot commodity in the global arms trade.

Today, China is the leading AK manufacturer, and primarily exports its weapons to African countries. It’s there, the Guardian reports, that the weapons “can end up on the illicit market either because underpaid soldiers sell them on, or because rates supply rebel forces in other countries.”

A UN investigation found that Libya — in the throes of its own conflict — is a major funnel for the AKs, passing them illegally to 14 countries including Tunisia, Niger, Syria, and Gaza, thus fueling and further exacerbating conflicts around the world. Hundreds of thousands of AK-47s remain in eastern Europe as remnants of the Balkan Wars and, true to their reputation, still function.

These decades-old guns, the Guardian writes, often find their way into black markets for illicit firearms — where terrorists can purchase them. Case in point: the 2015 Paris massacres, as well as the spate of terrorist attacks that took place in Europe that year. As the Guardian points out, more terrorist attacks were carried out with Kalashnikov-type assault rifles that year than with any other device.

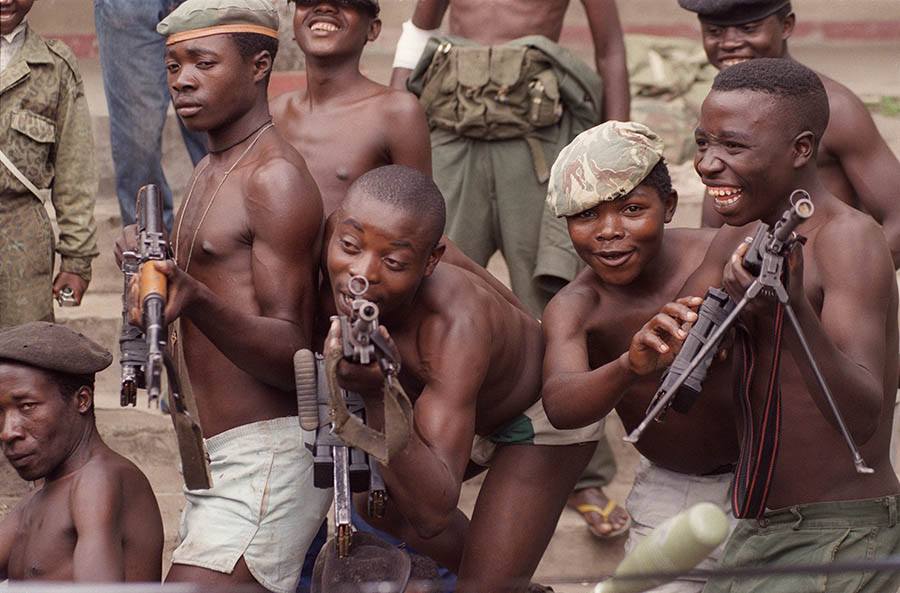

ABDELHAK SENNA/AFP/Getty ImagesZairian Tutsi rebel children soldiers play with AK-47 Kalashnikov assault rifles and sub-machine in November 1996.

In sub-Saharan Africa, Fountain writes that the weapon has “moved from being a tool of the conflict to the cause of the conflict.” Evidence for this can be most plainly seen in South Sudan. In summer 2014, China North Industries Corporation sold South Sudan approximately $20 million worth of automatic rifles and ammunition. Soon after, the country erupted in civil war, and experts doubt that the presence of nearly 10,000 Kalashnikov rifles will expedite its resolution.

While it certainly isn’t the case that AK-47s alone are to blame for these conflicts, when paired with poor governance and proximity to nearby conflicts, the AK can endanger more than it protects. As Global Risk Insights writes, the Kalashnikov is “a key ingredient for disaster in the developing world.”

And given the weapon’s masterly design, experts don’t see this changing any time soon.

“It’s a very simple piece of kit,” Mark Mastaglio, a UK-based ballistics expert, told the Guardian. “It’s very easy to use, that’s why you see 12-year-olds carrying them. It is tough, it works in all kinds of environments – hot and sandy deserts, or in Siberia. Wherever it is stored it is resilient, and this is why it is so popular.”

Mikhail Kalashnikov Changes His Tune

VASILY MAXIMOV/AFP/Getty ImagesRussian honour guard soldiers march around the coffin of Mikhail Kalashnikov (portrait seen at left), the designer of the iconic AK-47 assault rifle.

For most of his life, Mikhail Kalashnikov never indicated that he felt any remorse for his invention and its destructive potential.

“My aim was to create armaments to protect the borders of my motherland,” Kalashnikov once said in an interview. “It is not my fault that the Kalashnikov became very well-known in the world; that it was used in many troubled places. I think the policies of these countries are to blame, not the designers.”

Closer to his death, however, things — including Kalashnikov’s attitude toward what kinds of behaviors his weapon enables — started to change. “The longer I live, the more often that question gets into my brain, the deeper I go in my thoughts and guesses about why the Almighty allowed humans to have devilish desires of envy, greed and aggression,” Kalashnikov continued.

As his near-death missive makes clear, this guilt would shake Kalashnikov to his core — so much so that he would state that he wished he had invented something entirely different, something that might have made his parents’ lives as poor Siberian farmers a bit easier.

“I would prefer to have invented a machine that people could use and that would help farmers with their work,” Kalashnikov said during a visit to Germany.

“For example a lawn mower.”

Intrigued by the tale of Mikhail Kalashnikov? Next, read about Thomas Midgley, another inventor whose inventions spelled danger for millions. Then, meet the 106-year-old Armenian woman forced to protect her home with an AK-47.