The 100 rooms of the H. H. Holmes house were allegedly filled with trapdoors, gas chambers, staircases to nowhere, and a human-sized stove.

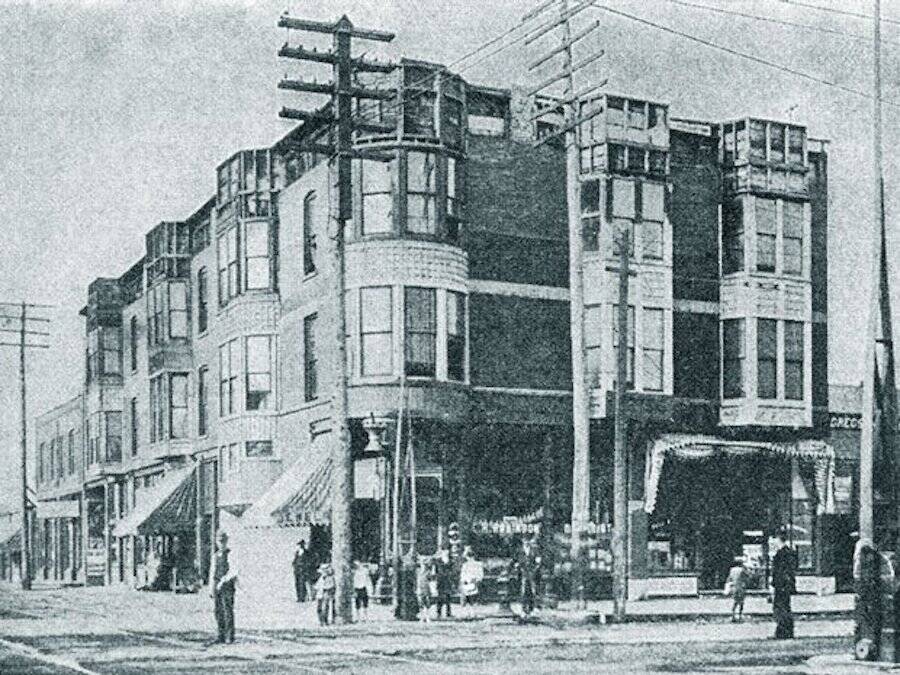

Wikimedia CommonsThe infamous H. H. Holmes hotel in Chicago, built in the late 19th century.

If you were staying at the World’s Fair Hotel — more commonly known as the H. H. Holmes hotel — you might run up a flight of stairs and find that it led to nowhere.

You’d open doors and see only solid brick. You’d enter a bedroom and suddenly smell gas seeping in. You’d try to run, only to realize you were locked in. Even if you could open the door, you probably couldn’t find your way out of the house. And before long, you’d meet your gruesome end.

Or at least, that’s how the story of the H. H. Holmes house goes. As one of America’s first known serial killers, H. H. Holmes became infamous not only for his crimes but also for his legendary “murder hotel” in Chicago. Sometimes called a “murder castle” or a “murder mansion,” this mysterious building was initially believed to be a normal hotel — and just a way for Holmes to make money during the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

But a police investigation later revealed something far more sinister. While it remains unknown how many people Holmes murdered in his house of horrors, he once boasted of killing 27 people. However, some estimates claim the actual number may have been as low as 9 — or as high as 200.

In recent years, some historians have cast doubt on whether the H. H. Holmes house was really a “murder castle” at all. While there’s no doubt that Holmes was a serial killer, experts have suggested that some of the most sordid details of his home — like the homemade gas chambers and trapdoors — may have been mere products of yellow journalism.

But at the end of the day, only the man himself ever knew all of the secrets of the H. H. Holmes hotel — and how many people died within its walls.

H. H. Holmes Arrives In Chicago

Wikimedia CommonsA mugshot of serial killer H. H. Holmes from 1895.

H. H. Holmes first came to Chicago in 1886, leaving behind more than one previous life. Born Herman Webster Mudgett, previous scandals gave him good reason to change his name.

Like in college, when he worked in the anatomy lab and mutilated cadavers to defraud life insurance companies. Or when he was the last person to have been seen with a missing little boy in New York. Or when he worked as a pharmacist in Philadelphia and a customer died after taking his pills.

After all these incidents, Mudgett simply skipped town and eventually changed his name to Henry Howard Holmes. Soon after his arrival in the Windy City, Holmes got a job in a drugstore on 63rd Street, using his knowledge of medicine and his charming personality to secure the position.

Holmes was fashionable, bright, and likable. In fact, he was so likable that at one point in his life, he was married to three unknowing women at once.

In 1887, he bought an empty lot across the street from the store where he worked and began construction on a three-story building, which he said would be used for apartments and shops.

The structure was ugly and large — containing more than 100 rooms and stretching for an entire block. But Chicago was a city on the rise, and new construction was going up all over this part of the American Midwest.

After all, Chicago was perfectly situated on the shores of Lake Michigan as a central hub for the expansive railroad networks that crisscrossed the nation, all extending like spokes in a wheel from the city.

Little did residents know that a house of horrors was about to emerge in that very same place.

The H. H. Holmes Hotel, The “Murder Castle” Of Chicago

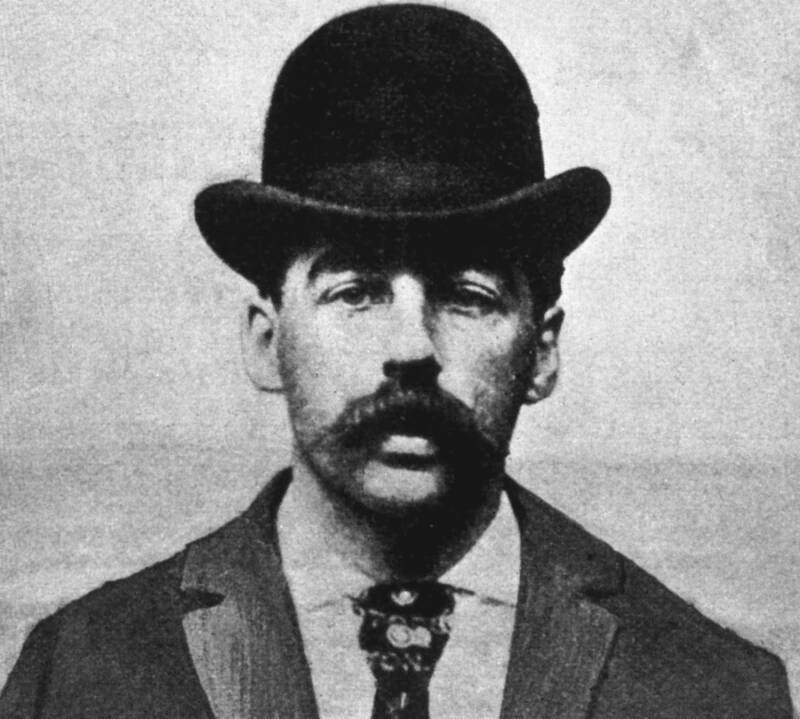

Holly Carden/Carden Illustration/Purchasable hereAn artist’s illustration of the H. H. Holmes hotel.

For his mansion, H. H. Holmes planned for the first floor to contain an entire block of storefronts that he would be able to rent out to the flood of new businesses opening up in the city.

The third floor would contain apartments for new residents looking to make it big in the Windy City. Eerily, some of those unsuspecting residents may have eventually become Holmes’s victims.

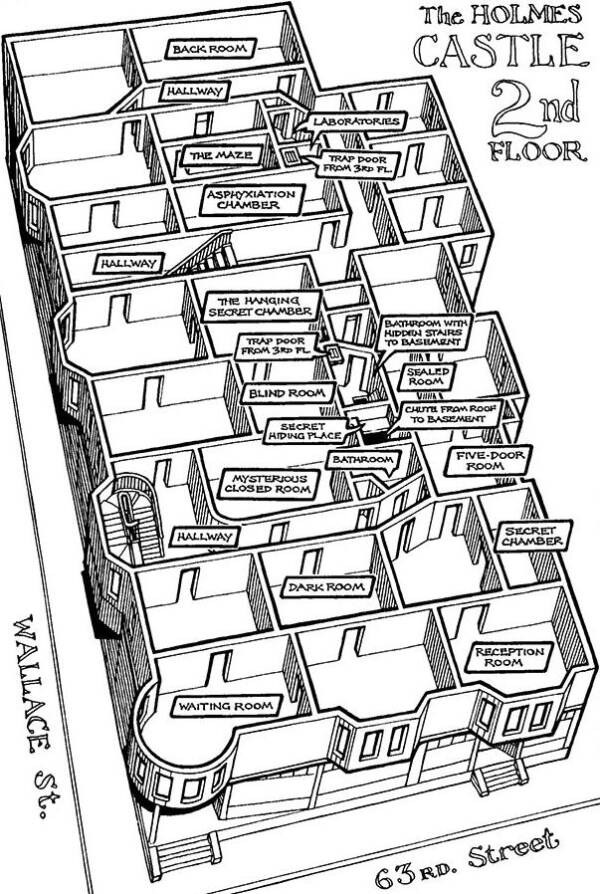

Those victims got to see the second floor — one that was allegedly full of “asphyxiation chambers,” mazes, and hidden stairs. And the especially unlucky victims made it down to the basement, which hid the elaborate horrors for which the H. H. Holmes house is now famous.

Throughout the building’s construction, Holmes apparently switched builders and architects frequently, so that no one involved was able to realize the gruesome end goal of all the odd parts.

The house was completed in 1892. And by 1894, police would be exploring its winding passages while Holmes sat behind bars. At first, authorities were confused by what they found.

ImgurThe second floor of the H. H. Holmes house.

There were hinged walls and false partitions. Some rooms had five doors and others had none. Secret, airless chambers were found underneath floorboards — and iron plate-lined walls appeared to stifle all sound.

As for Holmes’s own apartment, it had a trapdoor in the bathroom, which opened to reveal a staircase that led to a windowless cubicle. In the cubicle, there was allegedly a large chute that tunneled through to the basement. (Spoiler alert: It wasn’t used for dirty laundry.)

One notable room was lined with gas fixtures. Here, Holmes would apparently seal his victims in, flip a switch in an adjacent room, and wait for the horror to unfold. Another chute was found nearby.

All of the doors and some of the steps were connected to an intricate alarm system. Whenever someone stepped into the hall or headed downstairs, a buzzer sounded in Holmes’s bedroom.

It should be noted that these descriptions have been met with some skepticism by historians — especially in recent years — and so it’s worth keeping in mind that at least some of the designs may have been exaggerated or even invented by the newspapers of the era.

Uncovering The H. H. Holmes Murder Hotel

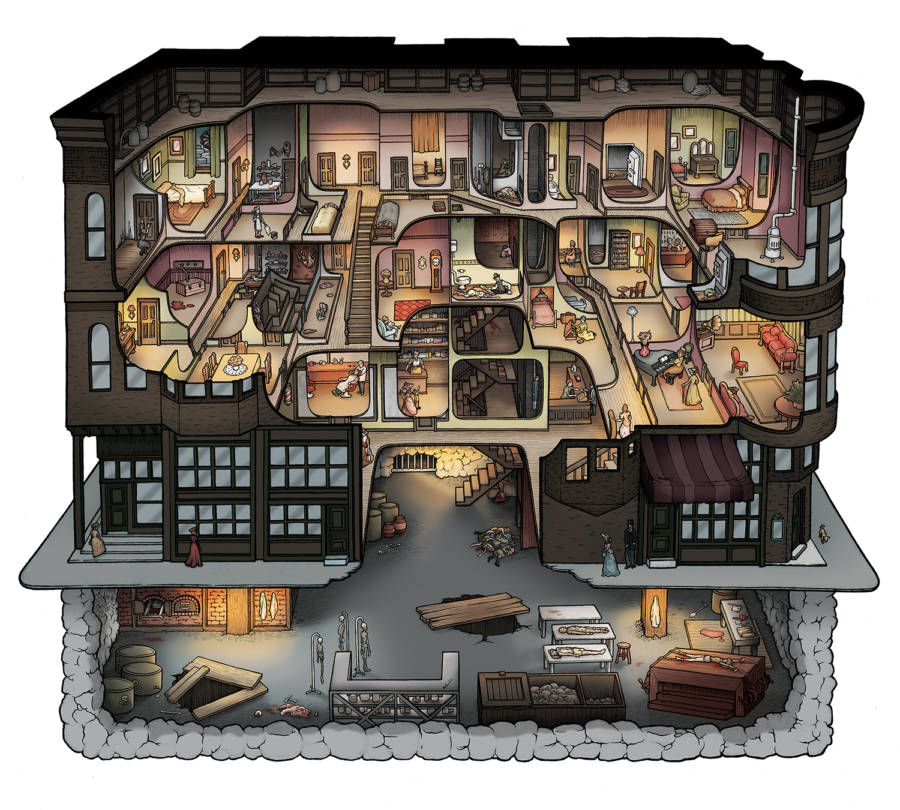

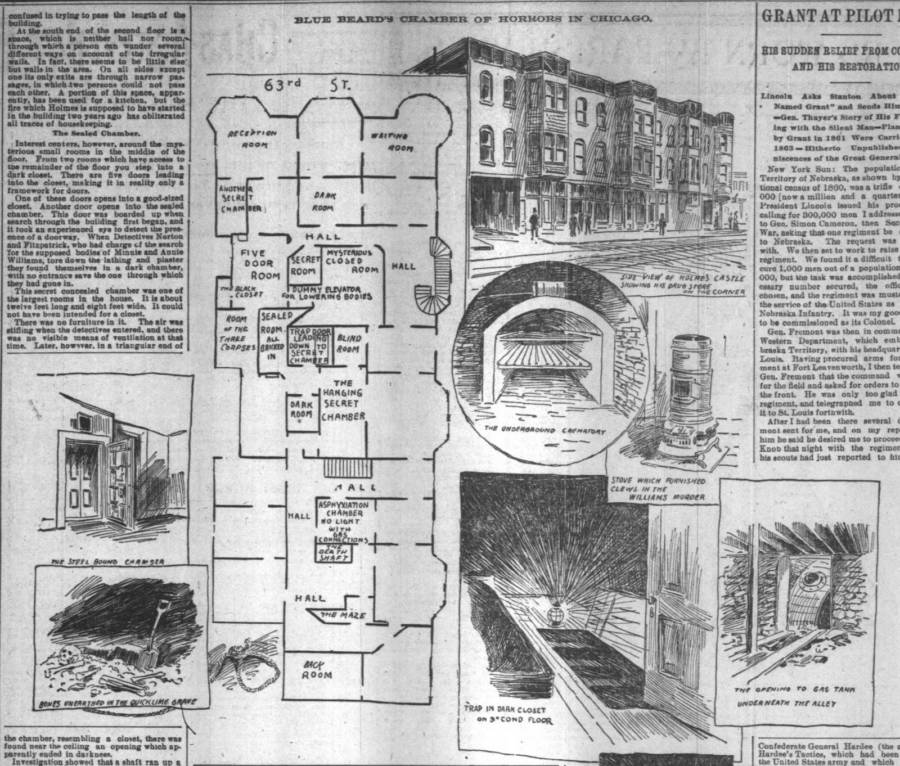

Illinois State Historical LibraryAn old newspaper floor plan of the H. H. Holmes hotel.

The first clue about the bizarre floor plan’s true purpose came to the cops in a pile of bones.

Most of the bones were from animals, but some of them were human. They were so small that they almost certainly belonged to a child, one who was no more than six or seven years old.

And when authorities descended into the cellar, the scope of the building’s hidden horrors was finally revealed.

Beside a blood-soaked operating table, they found a woman’s clothes. Another surgical surface was nearby — along with a crematory, an array of medical tools, a bizarre torture device, and shelves of disintegrating acids.

Holmes’s fascination with dead bodies had apparently lasted long past college, as had his surgical skills.

After dropping his victims down through the chutes, he reportedly dissected them, cleaned them, and then sold the organs or skeletons to medical institutions or on the black market.

How An Influx Of Transient Workers Provided Fresh Boarders

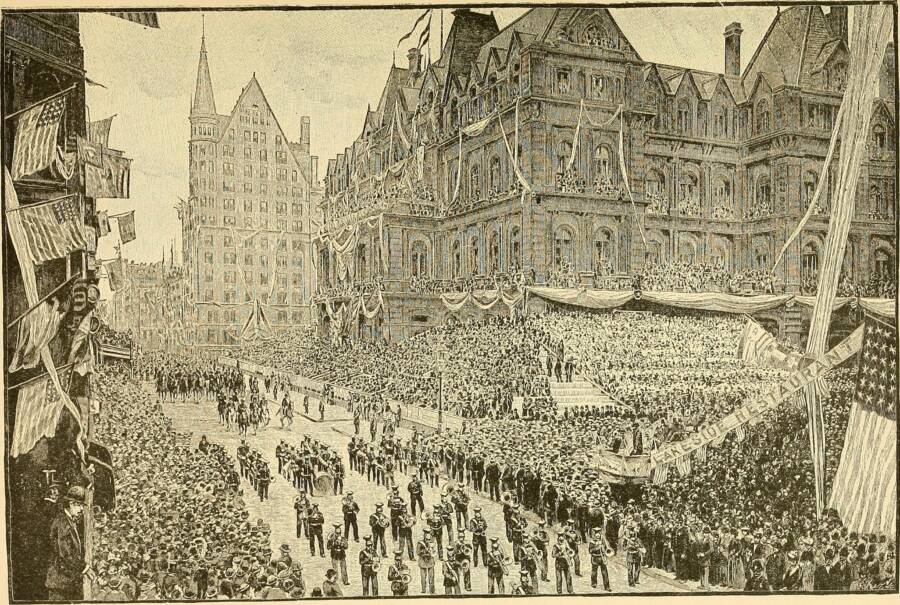

Wikimedia CommonsA sketch of the opening of Chicago’s Columbia Expedition, also known as the World’s Fair, in 1893.

Though the mansion didn’t look inviting in the least, it’s unlikely that any of the victims were dragged into its depths. They entered on their own volition, likely enchanted by the owner’s flattery and apparent affluence.

In some cases, they may have even been his employees. During his two short years in the castle, Holmes hired more than 150 women to work as his stenographers. A few of them were known to be his mistresses as well.

Holmes sometimes photographed his favorites. They were young, beautiful, and trusting of this gentleman in the big and unfamiliar city.

As a city on the rise that was well-connected thanks to its railway hub, Chicago undoubtedly had a fresh flow of people coming in and out of Holmes’s mansion.

But despite the well-connected women who went missing under his employment, suspicions of murder weren’t what led to Holmes’s demise.

Illinois Historical SocietyAn illustration of H. H. Holmes in a newspaper from the time.

People come and go all the time in a big city, often without notice. And before the age of advanced technology, it was especially hard to trace them. So the disappearance of the young women working under Holmes could’ve always been excused as them simply moving on or heading back home.

Ultimately, theft and poorly-planned financial schemes were what led to the arrest of Holmes in Boston on November 17, 1894.

After decades of criminal activity (the scale and complexity of which you really need a book to fully grasp), H. H. Holmes was behind bars.

While he was in jail, connections between him and at least one murder were revealed — and a pile of financial charges were obscured by the more sinister accusations that emerged. When all was said and done, Holmes was officially linked to 9 murders total.

Though he boasted of committing at least 27 murders, he gave three different confessions while imprisoned — all with contradicting numbers.

The true amount of victims was impossible to corroborate because the home was specially equipped for Holmes to disintegrate leftover body parts in acid baths or to burn them in a human-sized stove. (In one pile of ashes, investigators found a small gold chain from a woman’s shoe.)

The Devil In The White City

Boston Public Library/FlickrA painting of the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. The attendees allegedly provided H. H. Holmes with a constant supply of new victims.

“I was born with the devil in me,” Holmes would later explain. “I could not help the fact that I was a murderer, no more than the poet can help the inspiration to sing.”

As recounted in Erik Larson’s book The Devil In The White City, H. H. Holmes began his murder spree at a moment in history when an unprecedented throng of unknown, unaccompanied strangers were flooding the streets of Chicago, looking for temporary housing.

The 1893 Chicago World’s Fair was one of the most attended cultural events of the era, with millions of people participating in the historic celebration.

Noting the thousands of people who went missing during the World’s Fair, some papers suggested the actual count of Holmes’s victims may have numbered in the hundreds.

Smithsonian Institution Archives/PicrylA picture taken of “The White City,” as the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 would come to be called.

For the most part, Holmes represented himself at his trial — displaying his classic grace and a “remarkable familiarity with the law,” according to one paper of the time.

However, his charm wasn’t enough for the jurors — and he was unanimously sentenced to death by hanging.

Very familiar with what could be done to a person’s corpse after death, Holmes asked if his body could be encased in cement within his coffin.

Shortly before his death in 1896, H. H. Holmes suggested that he was turning into the devil. Even his face, he said, was taking on a demonic look.

His execution was an agonizing affair. When the floor was dropped beneath him, his neck didn’t snap like it was supposed to. He lay twitching for about 20 minutes before he was pronounced dead.

Strange Deaths In The Aftermath Of The H. H. Holmes Hotel Being Uncovered

Later, strange fates befell the people connected to the case of the H. H. Holmes hotel.

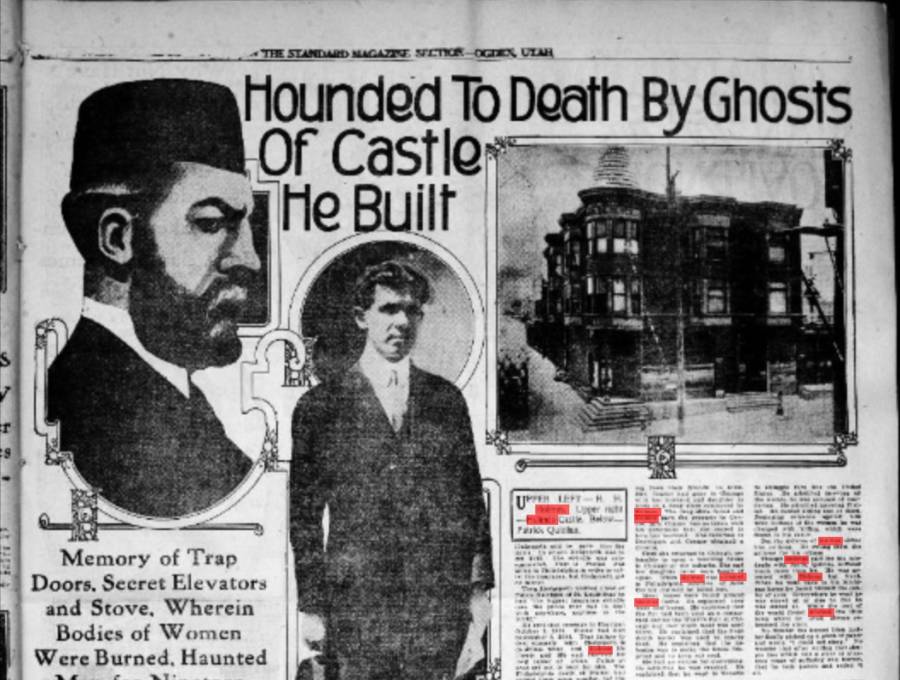

Library of CongressArticle on the suicide of mansion caretaker Patrick Quinlan from The Ogden Standard in 1914.

The man who had initially tipped off the police to H. H. Holmes’s illegal dealings was shot by a Chicago police officer. The warden at the prison where Holmes had been held killed himself. The office of the district attorney (who argued the famous case) caught on fire.

And Patrick Quinlan — the former caretaker of the castle who, after Holmes, knew the most about the haunted building — died by suicide in 1914.

He left a one-sentence note: “I could not sleep.”

As for the murder castle itself, it is no longer standing today. In 1895, the mansion was gutted by a fire — which may have been started by two men who were seen entering the building at night. The remaining structure was torn down in 1938. And today, the H. H. Holmes house is the site of an unassuming post office.

After this tour through the H. H. Holmes hotel, read about the hospital serial killer who was known as “The Angel of Death.” Then, check out the tale of “Lobster Boy,” the circus performer who became a murderer.