Today, H. H. Holmes lives on in infamy as "America's First Serial Killer," but the story we've all been told may not be completely true.

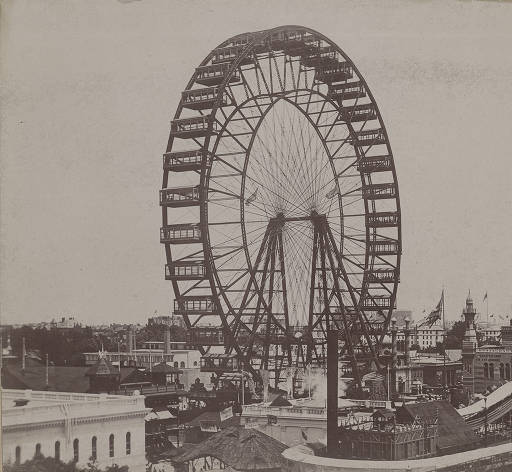

Of the great mass of people staring up at the towering white structures in Chicago’s Jackson Park and enjoying the sight of the world’s first Ferris Wheel, no one knows that the blue-eyed devil walks among them. His name — or, rather, his latest name — is Dr. H. H. Holmes.

There are millions of people, from all over the world, gathering in the United States’ second-largest city to see the 1893 World’s Fair — with the specially-constructed White City recreation area at its heart.

The White City’s Greco-Roman marvels surround Jackson Park, with structures that are taller and more dazzling to the eye than most of its visitors have ever or will ever see again in their lifetimes.

They were designed by the country’s finest architects — such as Stanford White, Charles McKim, and Daniel Burnham — and its gardens and grounds crafted by Fredrick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect who designed New York’s Central Park.

Smithsonian Institution Archives“The White City” of the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Never had so much legendary architectural talent come together to collaborate on a project like this one, and scarcely would there ever be anything like it again.

From all over the United States, people who would otherwise have lived and died in a small village in the Northeast or in a town nestled in a Rocky Mountain valley traveled great distances to see the White City. But whatever inspired them to come had not in any way prepared them for the breathtaking reality of it.

Now and again, H. H. Holmes approaches a passerby, likely a young, attractive woman brought here by the gossip back home from someone who had already visited the White City or by a newspaper reporter who’d described its wonders.

With more than 27 million people flooding in from around the world to see the fair, Holmes has plenty of women to choose from. With practiced courtesy, he offers her a room at his hotel nearby. Flattered at this handsome stranger’s hospitality, she takes him up on the offer.

Chicago History MuseumThe Chicago World’s Fair saw the first-ever Ferris Wheel, built for the event by George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. as America’s answer to the Eiffel Tower, which was built for the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, France.

That night, as his newest victim settles into her rented room, her host scurries around in his secret passages and hallways, using every piece of the self-designed house for a macabre purpose.

From within a secret hiding place behind a wall, Holmes turns a gas valve and watches as the sealed, air-tight room containing his victim on the other side of the wall fills with deadly, suffocating gas.

Before being brought to justice in November 1894, H. H. Holmes will have committed this gruesome act between two dozen and 200 times.

Or at least that’s how the story goes.

H. H. Holmes: A Man Of Myth And Mystery

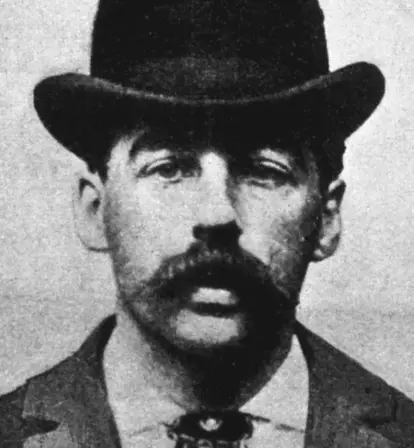

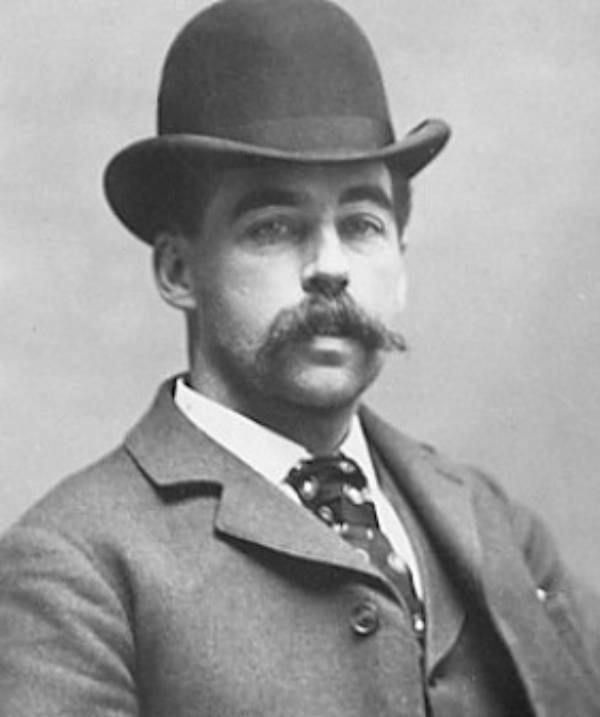

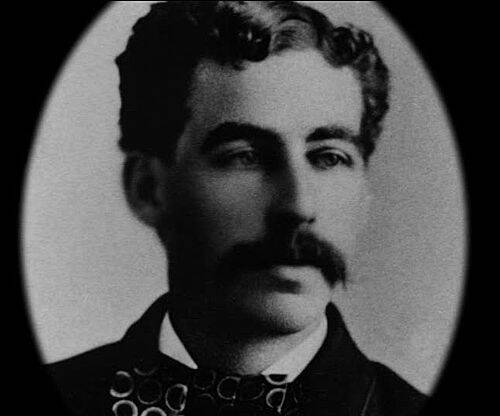

Wikimedia CommonsH. H. Holmes, whose “hotel” was said to have been an elaborate murder mansion where 25 to 200 people may have been killed.

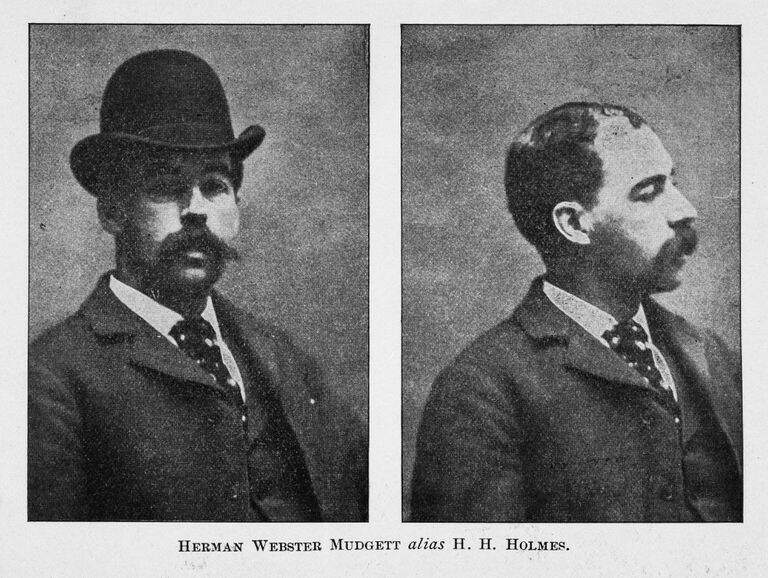

Herman Webster Mudgett, who would rename himself “Henry Howard Holmes” a.k.a. H. H. Holmes, was a difficult man to truly know.

Whether it was insurance fraud, quack medicine, fake inventions, or elaborate schemes to hide cash from creditors, no con was beneath him so long as there was money in it.

He was a compulsive liar who rarely looked people in the eye, creating new names and backstories for himself to suit his purposes. Sometimes he was the son of an English Lord. Other times he had a wealthy uncle in Germany.

But what is mostly certain is that Holmes would kill nine people in a series of increasingly desperate tricks and manipulations in the first half of the 1890s. So, why do so many people believe the “real” body count to be anywhere between 25 and 200?

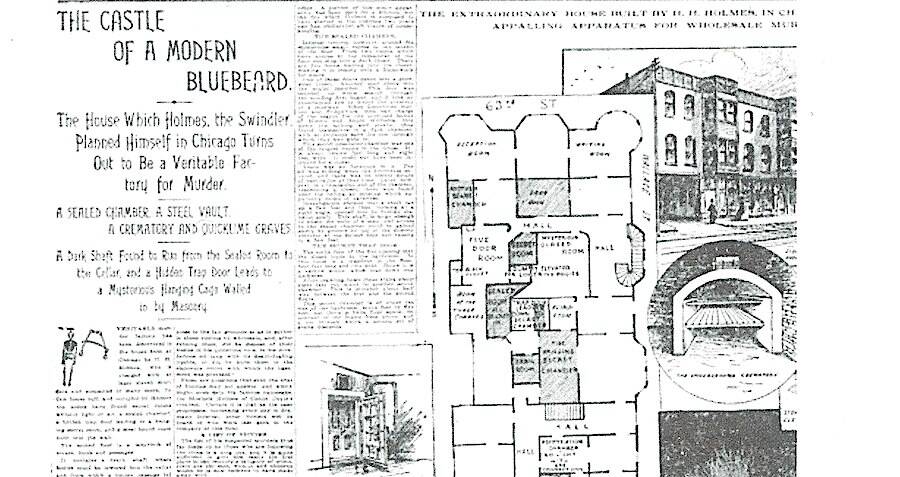

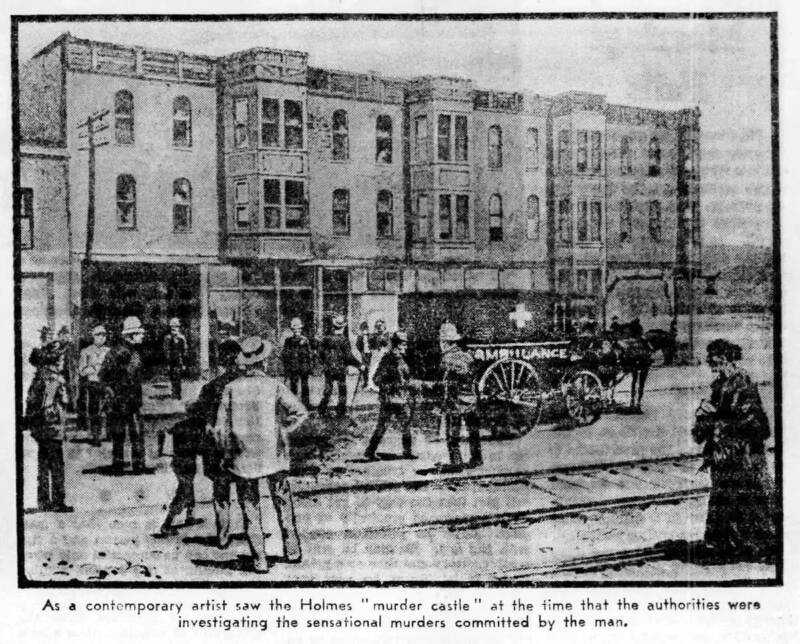

Wikimedia Commons.New York World’s 1895 Article on HH Holmes’ “murder castle”, originating many of the modern myths.

The picture of H. H. Holmes that has been rendered unto history, a picture recently revived in Erik Larson’s 2003 book The Devil in the White City, is the one that has existed since Holmes himself was alive.

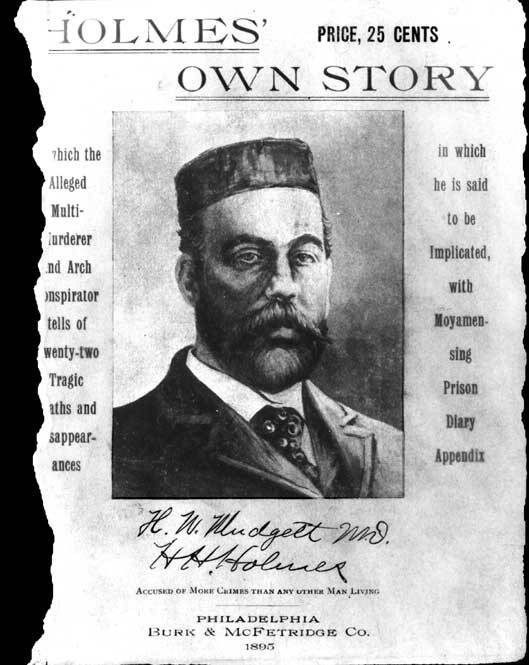

Dubbed a “modern Bluebeard” by William Randolph Hearst’s New York World, Holmes had become a nationwide sensation by the time of his November 1894 arrest and 1895 trial — the first for insurance fraud, the latter for murder. He was America’s answer to Jack the Ripper, whose grisly murders across the Atlantic had left readers spellbound seven years earlier.

A modern, urban monster for a modernizing and increasingly urban age, Holmes was, according to Chicago police, a “new class of criminal,” a man so monomaniacal about manslaughter that he turned his own hotel into a “Murder Castle.”

An apparently perfect image of evil in human form — said to believe he was actually turning into a devil while incarcerated — H. H. Holmes is often described today as “America’s First Serial Killer,” an honorific taken from Harold Schechter’s book about his crimes, Depraved.

But, are this appellation and the story behind it accurate? And if not, where did they come from?

In his 2017 book, H. H. Holmes: The True History of the White City Devil, author Adam Selzer attempted to answer these questions by studying newly digitized court records, police files, newspaper reports, and interviews previously unavailable to other authors.

Ultimately, the details and discrepancies he uncovered raise serious questions about how much “truth” there is to the traditional tale of H. H. Holmes.

After examining the evidence, H. H. Holmes may still have been a monster, just not the devil we think we know.

“I Was Born With The Devil In Me”

Herman Mudgett was born in Gilmanton, New Hampshire in 1861. Finishing school at age 16, Holmes became a teacher and soon set his sights on a local girl, Clara Lovering.

Though Holmes convinced her and her family to consent to marriage, the relationship soured almost as soon as she became pregnant.

At 19, Holmes then left New Hampshire to study medicine, abandoning Clara and their infant son, Robert.

After first enrolling at the University of Vermont, Holmes left for the University of Michigan either to move farther away from his family or because of the latter curriculum’s cutting-edge emphasis on human dissection (accounts vary).

Rumors and anecdotes from those who knew him at this time repeatedly mention his habit of stealing medical cadavers, both intact and in pieces.

In one story told by his Burlington landlady, she “noticed a foul stench in Holmes’s room emanating from a ‘dark object’ under the bed. Using the broom, she swept the object out and found that it was a dead baby.”

But according to his Michigan classmates, H. H. Holmes was quiet, serious, and somber. He didn’t talk much and, though he was a bit strange, he appeared mostly harmless.

YouTubeClara Lovering, H. H. Holmes’ first of four “wives,” whom he abandoned to study to become a doctor.

Apart from stealing the occasional corpse or foot, most people remembered that he was training to be a missionary in Zululand — a lie — and a few others vaguely recalled an incident with a local widow.

In his last year of medical school, Holmes was sued for “breach of promise,” quite a serious crime at the time. His accuser claimed that Holmes proposed to her and consummated their “relationship” only to have her later find out that he was already married.

If true, the charges could have prevented him from graduating.

When the case became public, many who knew Holmes in the faculty and student body felt this was out of character for him, including one Professor Herdman, who helped successfully defend him against expulsion in front of the school board.

Later, after his graduation ceremony, Holmes told Herdman that the widow had been telling the truth.

That moment, the professor later wrote, “was the first positive evidence I had received up until that time that the fellow was a scoundrel, and I told him so at that time.”

It was only later that Herdman realized that H. H. Holmes had also attempted to burglarize his house on two separate occasions.

The Early Criminal Career Of A Promising Young Doctor

Depending upon who you ask, H. H. Holmes’ more fatal games may have started in medical school.

In his 1895 autobiography, Holmes’ Own Story, Holmes claimed he and a Canadian classmate had plotted to steal cadavers from their laboratory and pass them off as other people to collect insurance money.

The plan, in Holmes’ retelling, centered around a certain local family — a man, a woman, and their young daughter — all of whom had been convinced to take out a life insurance policy. After the family had been convinced to leave town, Holmes and his accomplice would present three mutilated bodies of about the right ages and appearance, collect the money, and split the profits.

They also agreed to split the work. Somehow in the middle of a national cadaver shortage, Holmes claimed to have found a body in Chicago, but his partner never followed through.

He stored the corpse in a barrel where it remained until he moved to Chicago in 1886. By that time, it was so rotten that the only thing to do was bury it in his basement.

At least, that’s what he said when the police later found the human bones inside his house.

ImgurH. H. Holmes’ University of Michigan Graduation Portrait. 1884.

Following graduation, H. H. Holmes – still Herman Mudgett — set up in Mooers Forks, New York working two jobs as a doctor and schoolteacher. Though there are refuted reports of Holmes showing his students a severed foot or marrying a woman who then went missing, one perhaps-true incident from this period is particularly striking.

A Civil War veteran came into the office that Holmes shared with another doctor named Steele. He was near death from what he claimed was an old war wound and asked that the physicians perform an autopsy to eventually confirm this in order to secure a military pension for his wife.

Holmes enthusiastically agreed.

When the man died, Holmes successfully located the bullet that had been lodged in his chest for more than 20 years. He then removed the bullet, along with the dead man’s shattered ribs, and refused to hand them over unless Steele paid him for them.

Steele, who already had enough evidence to confirm the nature of the injury and cause of death, refused. As far as Steele knew, Holmes kept the ribs.

It’s possible Steele had his own reasons for telling this story. In their last interaction, Holmes asked to borrow money for a train ticket to Chicago.

He never returned to pay back the debt, but he did leave other things behind. One was a box containing all mementos leftover from his life up to that point. The other was the name Herman Mudgett.

How H. H. Holmes Bought And Built His “Murder Castle”

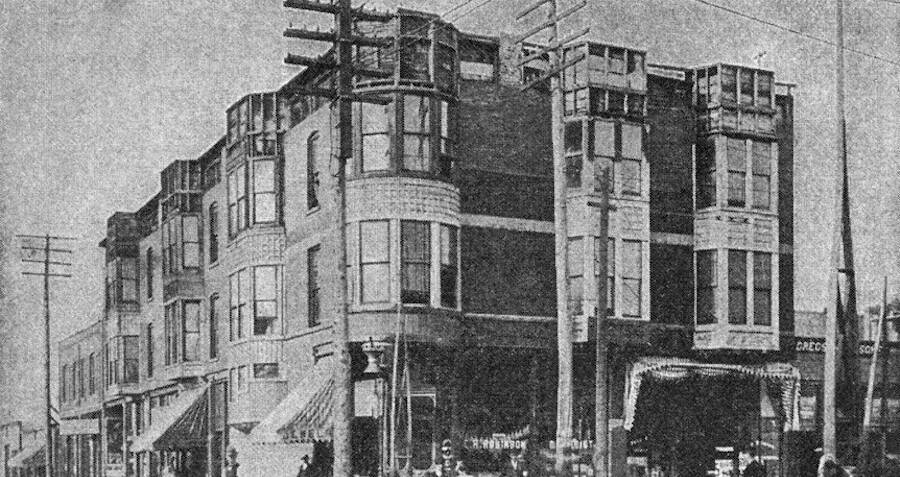

Wikimedia CommonsH. H. Holmes’ murder mansion. Though there are rumors that as many as 200 people were gruesomely killed within its walls, doubts are starting to be raised about whether Holmes was the devil he has been made out to be.

Why he chose the name H. H. Holmes has garnered speculation over the years. Several authors have suggested he was inspired by the popular Sherlock Holmes detective stories, but this is false.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories were enormously popular at the time of his 1894 arrest, but Sherlock Holmes first appeared in print in 1887’s A Study in Scarlet and an American edition was not published until 1890.

The name H. H. Holmes appears in Illinois newspapers and legal documents as early as 1886, when the new arrival took — and passed — a government test to practice pharmacy in the state.

After arriving in Chicago in 1886, Holmes visited Dr. E.S. Holton’s pharmacy on 63rd and Wallace in Englewood. In Larson’s Devil in the White City, the scene is sketched in vivid detail.

The elderly Dr. Holton lays on his death bed upstairs as Mrs. Holton eagerly sells the building to the young, handsome doctor, even though he cannot pay all at once.

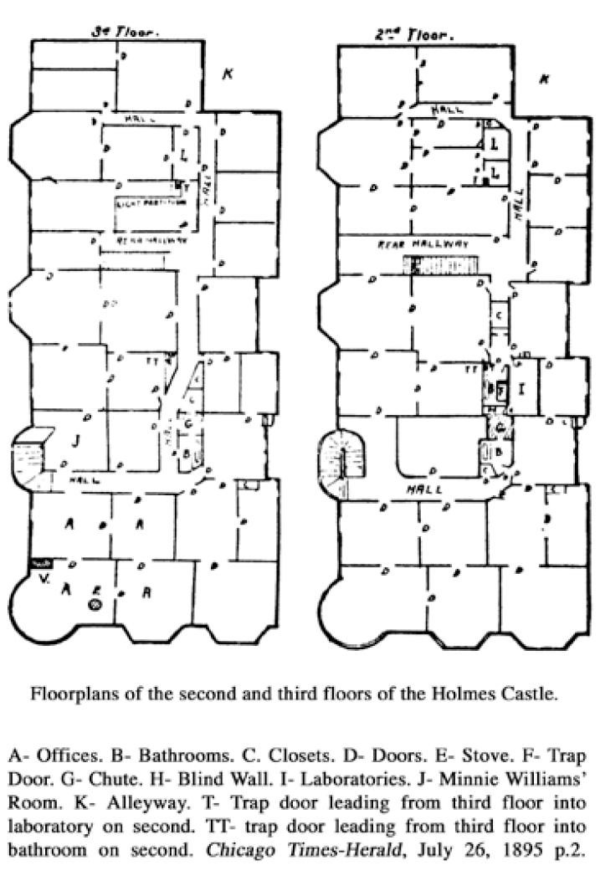

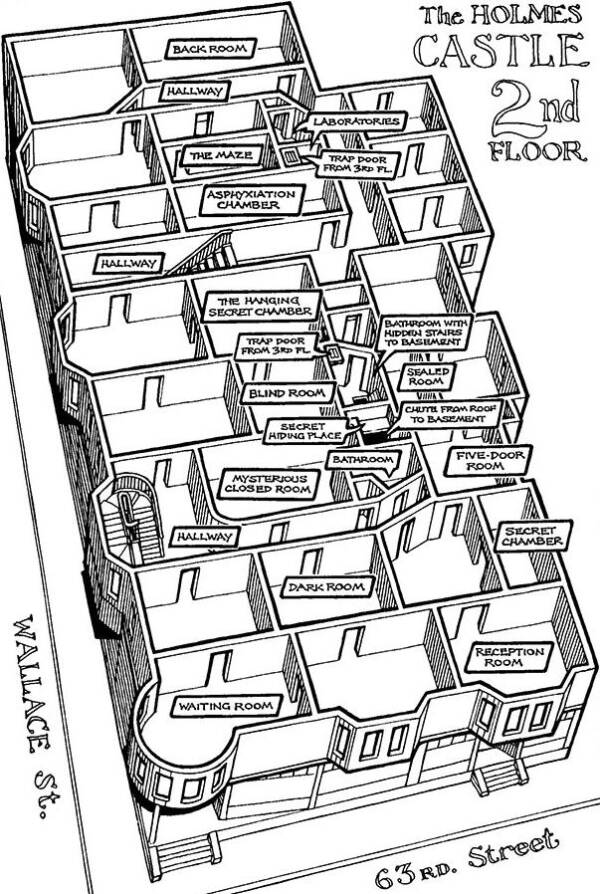

MurderpediaThe layout of the second and third floors of H. H. Holmes’ hotel, with the suspected purpose of each room, according to the press, listed.

Shortly after the building was rechristened under H. H. Holmes’ name, neighbors ask what happened to Mrs. Holton, who had apparently gone missing.

Holmes tells them she moved to California, but Larson, as well as other authors, strongly imply that he killed her and possibly Dr. Holton as well. But, what only Selzer seems to have noticed is that Dr. E.S. Holton was not an old man. She was a young woman.

Dr. Elizabeth Sarah Holton was pregnant at the time of Holmes’ arrival and apparently jumped at the chance to get off her feet.

By the time reporters and investigators were interested in H. H. Holmes and his infamous building, if the former owners were thought of at all, they were assumed to be other victims. In actuality, Dr. and Mr. Holton were alive and well a few blocks away.

After acquiring the two-story building, Holmes began a series of renovations. The most notable for those already familiar with the story are probably the so-called secret passages, false walls, dummy elevator shaft, trap doors, basement crematorium, and, eventually, a third floor outfitted with rooms to house World’s Fair attendees.

Did H. H. Holmes Ever Actually Run A Hotel?

ImgurThe reported layout of the second floor of the “murder mansion” of H. H. Holmes. Because it was right above the businesses below, could this floor consist just storage space?

In Devil in the White City, Erik Larson states that Holmes began advertising his new “World’s Fair Hotel” in 1893.

However, extant digitized newspapers and the state of Illinois Historical Newspaper Archive have no record of such a hotel. In fact, according to Chicago civil case documents, while Holmes did build the third floor to function as a hotel, it never actually functioned as one.

Before the hotel could open, H. H. Holmes’ creditors — his constant adversaries — repossessed the furniture he’d purchased, meaning the level was empty apart from his office and a large asbestos-lined vault.

It’s possible some particularly desperate fairgoers could have stayed there, but it seems unlikely and would have had to happen within an incredibly small window of time. At the height of the World’s Fair on August 13, 1893, a fire — possibly started by Holmes to collect an insurance payout — destroyed the third floor and forced the evacuation of the entire building.

In a statement to reporters by one of Holmes’ tenants, he said everyone made it out of the building safely, listing each of the residential and commercial tenants on the first two floors, notably a tailor, a pharmacist, and a jeweler. Neither a hotel nor any hotel guests were mentioned.

Wikimedia CommonsH. H. Holmes’ Englewood “castle” on 63rd and Wallace with its partially-destroyed third floor. 1896.

As to why Holmes would try adding a hotel to his building, it’s surprisingly not out of character.

During his time at 63rd and Wallace, Holmes ran a variety of strange businesses and “get rich quick schemes” out of the building: quack cures for alcoholism, a copy machine company, and a glass-bending studio to supply Chicago’s new skyscraper boom utilizing converted furnaces as kilns.

But, even if the central part of Holmes’ story involving his running of a hotel during the fair is inaccurate, the doctor was still a devil in his own right.

In addition to his habit of defrauding creditors, inventing aliases, generally figuring out how to commit every kind of fraud, and committing bigamy, H. H. Holmes was indeed a murderer.

The True Crimes Of H. H. Holmes

Not long after arriving in Chicago, H. H. Holmes met Myrta Belknap of Minneapolis while she was in the city on business. Following a quick courtship, he convinced her parents to let them marry, sweetening the deal by buying them a house.

Holmes, briefly reverting to Herman Mudgett, filed for divorce against Clara Lovering, claiming she had committed adultery. And while Holmes did marry Belknap, he did not see his divorce through to its conclusion.

It is unclear whether or not Belknap and Holmes married legally or simply had a religious ceremony, but before 1890, the couple was living together in Wilmette with their new daughter, Lucy.

Just as with Lovering, however, whatever affection Holmes may have had for his new wife faltered soon after his daughter’s birth. He took up residence at his office and his visits back to Wilmette became rarer and rarer.

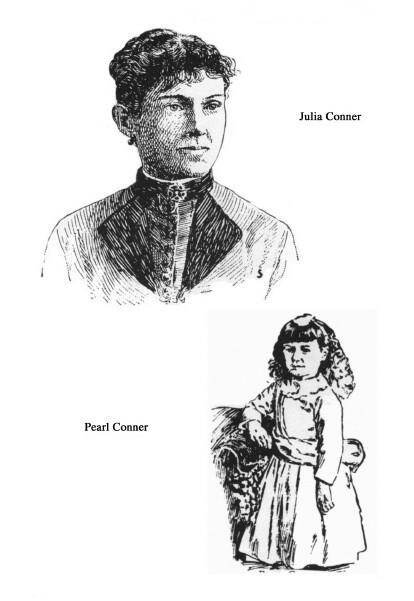

This is when the Conners arrived. Ned Conner, a jeweler, his wife, Julia, and their daughter, Pearl, took up residence at Holmes’ Wallace Street building in 1890.

MurderpediaIllustration of Julia and Pearl Connor, whom Holmes confessed to killing.

Offered a chance to buy the building, Conner excitedly agreed, only to discover it came with certain strings attached.

For one, H. H. Holmes neglected to tell him how much debt the store was in, debt Ned Conners now owned along with the location. Second, his marriage with Julia quickly fell apart with a surge of fighting leading to divorce, which was still uncommon at the time.

When he realized that Holmes and Julia were sleeping together, he began to wonder whether Holmes had implicitly offered him a trade: the store for his wife.

Ned moved out and sold Holmes the store back relatively quickly. What exactly Julia thought of all this remains uncertain.

In addition to the loans and business holdings he kept under his own name, his various aliases, Belknap’s name, and Belknap’s mother’s name, Holmes had now added Julia to his list of “responsible parties.”

But some time after that, Julia and Pearl, common sights around the Wallace Street building, suddenly disappeared. Holmes said they had gone to visit family, but they were never seen again.

The Missing Miss Cigrand

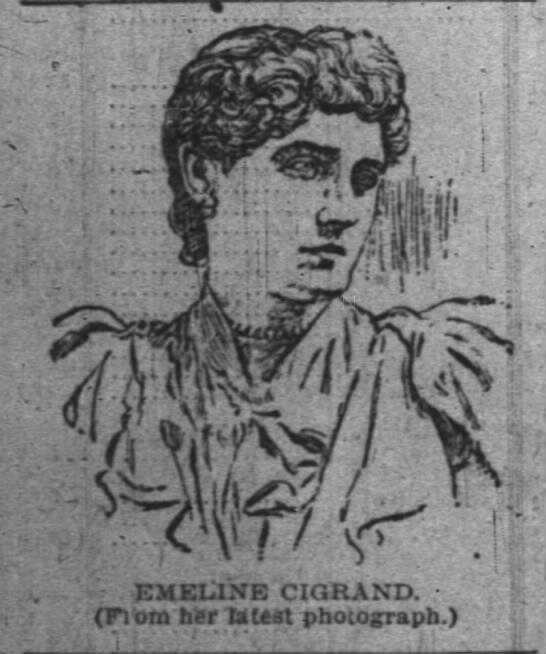

Emeline Cigrand was next. A beautiful young secretary and typist at a rival alcoholism clinic, Cigrand likely met H. H. Holmes through his frequent accomplice and “business partner” Ben Pitezel, whom Holmes had sent for treatment at the center.

However he learned of her, Holmes soon offered her double her current salary to work with him. When exactly their relationship turned intimate is unclear. It was technically a secret, but several residents of the house had their suspicions.

Shortly before Christmas 1892, Mrs. Lawrence, another of Holmes’ tenants, had her last encounter with Cigrand.

The younger woman offered her an early present and spoke in vague terms about the future, leading her neighbor to ask if she was leaving her job and possibly Chicago. Cigrand said “maybe” — and seemingly vanished after that.

A concerned Mrs. Lawrence then asked Holmes what he knew about her whereabouts. Ms. Cigrand, Holmes said, had married her fiancé Robert Phelps — whom no one had ever met or heard of before — and had left the city on her honeymoon, quite possibly to never return.

The Indianapolis NewsAn illustration of Emeline Cigrand, a young stenographer who Holmes is said to have murdered.

He produced a wedding card from his pocket, suspiciously typewritten instead of in the more traditional printed fashion, and Mrs. Lawrence felt uneasy. Surely, she thought, Cigrand would have told her about such a serious romance or said goodbye before leaving.

Apparently, H. H. Holmes did not like that answer. However, he did not kill Mrs. Lawrence. Instead, a few days later he returned with a newspaper clipping reporting the wedding of Emeline Cigrand to one Robert Phelps.

It began:

“The bride, after completing her education, was employed as a stenographer in the County Recorder’s office. From here she went to Dwight, and there from Chicago, where she met her fate.”

Although at the time no one suspected Holmes in Cigrand’s disappearance or of having written the newspaper announcement himself, in hindsight, it seemed — and seems — the most likely explanation.

In addition to noting the dual meaning of “met her fate,” Mrs. Lawrence later testified that sometime after Cigrand’s disappearance she witnessed Holmes, Pitezel, and another associate named Patrick Quinlan moving a heavy trunk from the third floor out of the building.

By that point, she was almost certain it contained the body of Emeline Cigrand.

The Unfortunate Williams Sisters

The Williams sisters came after that. H. H. Holmes met Minnie Williams on business in Boston sometime in the 1880s and saw two things he liked. Already a wealthy orphan, Minnie Williams could expect to inherit another small fortune after the death of her elderly guardian. Furthermore, Williams, often described as “plain,” could be flattered and manipulated easily.

Using the name Howard Gordon, Holmes swept Williams off her feet, gaining such control over her and her finances that she signed away several of her real estate holdings to him and moved to Chicago in 1893.

To limit complications, “Howard” explained that for “business reasons,” people called him H. H. Holmes in Illinois. Like many before and after her, for some reason, she believed him. The two “married” soon after her arrival.

No record of this marriage — Holmes’ third — is listed in the Cook County archives. While it could have been lost, it’s likely that Holmes simply arranged a sham ceremony.

ClickAmericanaMinnie Williams, another of H. H. Holmes’ “wives” who went missing and is believed to be another of his victims.

After their father’s death, different relatives raised Minnie Williams and her sister Nannie, who was sometimes incorrectly called “Anna,” a name she never went by in life. Minnie grew up in Boston while Nannie lived in Alabama. The two maintained a correspondence, but once Minnie’s letters mentioned her recent marriage to a handsome, rich, and charming doctor, they arranged for a reunion in Chicago.

In one of the few known instances where H. H. Holmes went to the World’s Fair, he treated the sisters to a day’s visit in celebration of his sister-in-law’s arrival.

Nannie was skeptical of “Howard” at first, finding him much less attractive than Minnie had described, but the more time she spent in his company, the more she understood why her sister wanted to stay with him.

As far as we know, neither of them ever left.

A Second Southwestern Castle?

Nannie disappeared first. That much is certain. Then H. H. Holmes traveled to Fort Worth, Texas with Minnie in tow to take possession of some land she held there leftover from her family’s estate.

Ben Pitezel joined them, assisting Holmes in the construction of a new building, modeled to be an identical duplicate of the Chicago drugstore, “secret passages” and all.

Holmes’ scheme here is unclear. While it’s tempting to say that he wanted to build a second “murder hotel,” this theory has a few problems.

In addition to the likelihood that it was not a functional hotel, Holmes’ building in Chicago may not have had secret passages at all. These features could easily have been storage spaces to hide excess stock and a “hidden” back staircase to allow employees to travel between the floors unseen.

Some employees, by the recollection of Ned Conner, occasionally even slept in the so-called hidden chambers. Considering Conner was then openly wondering whether Holmes had killed his ex-wife and daughter, this testimony in Holmes’ “defense” should have considerable weight. If he said there were no secret passages, there’s reason to believe that there were, in fact, no secret passages.

It’s also worth noting that during the time Holmes was supposed to be busy luring fairgoers to their deaths, he was several states away.

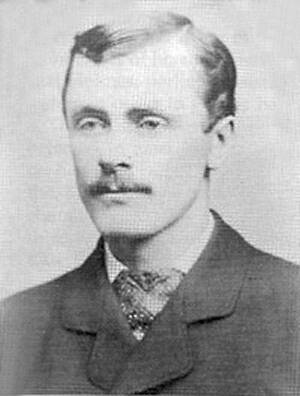

Wikimedia CommonsBenjamin Pitezel, Holmes’ longtime partner and eventual victim. Circa 1890s.

Holmes left Texas not long after the new building was finished. If he’d intended to build another lethal lair in Fort Worth, his departure would have made no sense. But, it does match another motive.

Although H. H. Holmes did not build the Englewood “murder castle” — he only remodeled it — many researchers suggest his habit of hiring and firing builders stemmed from his desire to keep its exact layout secret.

However, he did the same thing in Fort Worth and apparently never intended to live there. In both cases, the construction projects were just another con.

Borrowing from multiple banks and commissioning work with IOUs, Holmes amassed a great deal of laundered money while distracting his creditors with the progress on the building. Once the structure was finished, he left Texas.

It appears Minnie Williams, however, did not.

Murderpedia; ClickAmericanaIllustrations of Minnie (left) and Nannie (right) Williams, who disappeared and whose bodies were never found.

Several witnesses later testified to seeing Minnie Williams after this period. However, almost none of them knew her, and Holmes’ later admitted to paying Patrick Quinlan’s wife to impersonate the missing woman. Minnie and Nannie Williams’ bodies were never found.

H. H. Holmes’ Murder Of The Pitezel Family

Before returning to Chicago, H. H. Holmes was arrested in Colorado on fraud charges and spent the end of 1893 in prison.

After his release, in January 1894, Holmes met and extralegally married his fourth and final wife, Georgiana Yoke, while using the name “Mr. HM Howard.”

This time, Holmes explained that his wealthy uncle had left him a great deal of land in his will on the condition that he adopt the dead man’s name. Yoke apparently had no problem believing this, but she also had no way of knowing that Holmes’ land had been inherited from Minnie Williams.

Meanwhile, Ben Pitezel, his wife Carrie, and their children Dessie, Howard, Nelly, Alice, and Wharton had moved to St. Louis, Missouri. In 1894, Holmes contacted Pitezel asking him to purchase life insurance so they could fake his death with a medical cadaver. Pitezel agreed and the pair traveled to Philadelphia, but not before explaining the plan to Carrie.

Unfortunately for Ben Pitezel, this time — after many capers in which they’d been partners — H. H. Holmes was playing him.

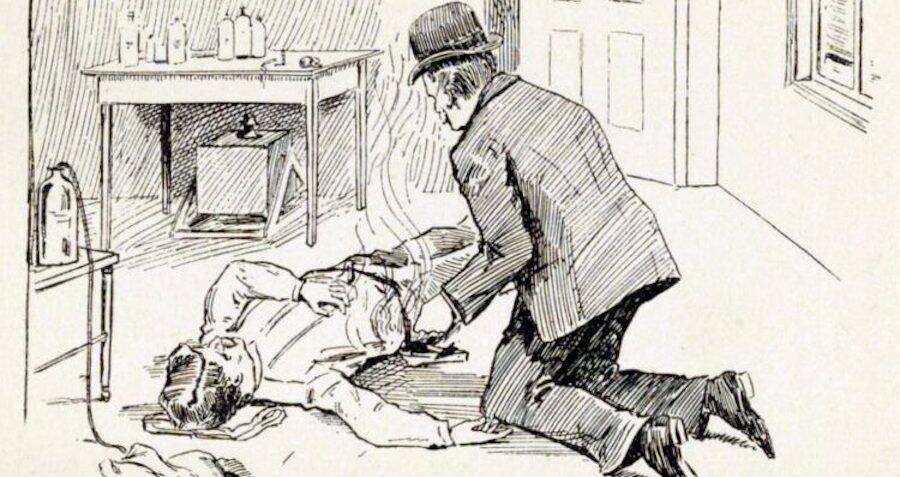

Once in Pennsylvania, Pitezel grew impatient waiting for his partner to find a body. To pass the time, he started drinking. Then, Holmes started pouring him shots.

Perhaps Holmes had planned to do it all along. Perhaps he was frustrated by Pitezel’s alcoholism. In either case, once the other man passed out, Holmes gave him a lethal dose of chloroform.

Using an oil lamp, he singed Pitezel’s hair and clothes before smashing the chloroform bottle on the floor. For some reason, he had decided to make it look like his partner had died in an accidental explosion.

He did a terrible job, but the Pennsylvania coroner bought it.

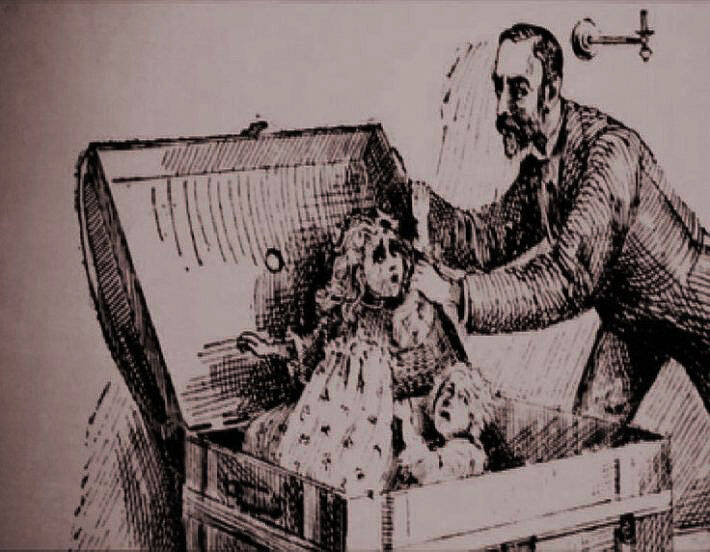

Public DomainA newspaper illustrator’s depiction of H. H. Holmes staging Ben Pitezel’s “accidental death.” Circa 1890s.

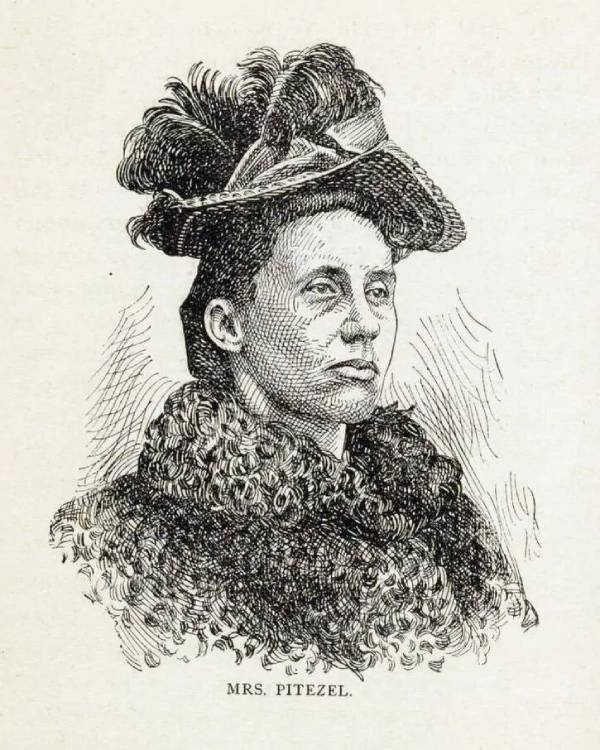

In order to collect the money from Fidelity Mutual Insurance, Holmes needed Carrie or another member of the Pitezel family to identify Ben’s body.

He sent a letter to St. Louis asking Carrie to come, explaining that it was, of course, a ruse. Unwilling to leave her infant son, Carrie Pitezel sent her 15-year-old daughter Alice to Holmes by train. They never saw each other again.

Alice, on the verge of relative adulthood, disliked the arrangement. Although Ben Pitezel and Holmes had worked together for years, Holmes was still a stranger to the rest of the family.

Things went from bad to worse, however, when Holmes brought Alice into the coroner’s office where a few sheets of cloth and paper were all that separated her from her father’s blackened, rotting corpse.

MurderpediaBenjamin Pitezel, longtime accomplice of H. H. Holmes, would eventually become his victim — along with three of his children.

With encouragement from Holmes, she was able to identify the body by its teeth, and Fidelity Mutual Insurance agreed to issue a check of $7,200 to Carrie Pitezel in St. Louis. Holmes then informed Carrie that Ben owed him $5,000, a debt she quickly paid.

Now that he had his money, two final problems presented themselves. First, the Pitezel family knew too much for H. H. Holmes’ comfort. Second, they believed that Ben Pitezel was still alive.

Thinking quickly, Holmes asked Carrie to send two more of her children to him in Philadelphia. Ben was hiding in Cincinnati, Ohio, but a visit from such a large, conspicuous, and recognizable group of people traveling together would draw too much attention and blow the entire plan.

It was then that Carrie sent her son Howard, age eight, and daughter Nelly, age 11, to join Alice and Holmes in Pennsylvania. She and her two remaining children, the eldest, Dessie, and the youngest, baby Wharton, would wait a little longer before heading out to meet them.

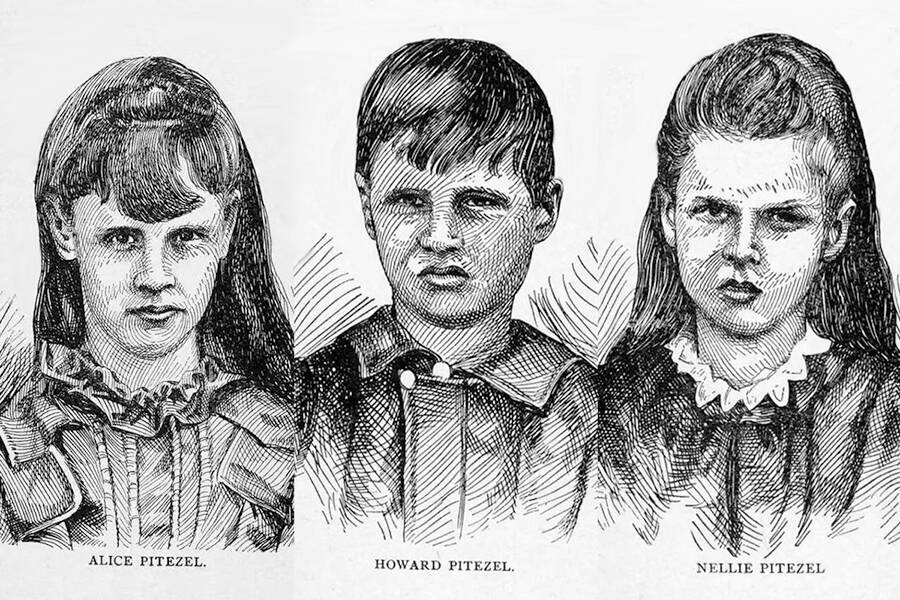

ClickAmericanaIllustrations of the Pitezel children — Alice, Howard, and Nellie — who were all murdered by H. H. Holmes.

What follows is a dizzying display of Holmes’ cunning intelligence and inhuman cruelty, but even he seems to have suffered the consequences of some of his actions. According to Yoke’s later testimony, Holmes suffered from chronic nightmares during this period, apparently haunted by the sight of Ben Pitezel’s rotting corpse.

But from September 28 to November 17, 1894, Holmes successfully juggled navigating eight people in three separate groups — Holmes and Georgiana, the three Pitezel children — and a third group with Carrie Pitezel, her baby, and Dessie — across much of the Midwest and into Canada. Without anyone else knowing what he was doing or where the other parties were.

They traveled from Cincinnati, Ohio to Indianapolis, Indiana then to Detriot, Michigan then to Toronto, Canada then to Ogdensburg, New York.

Whenever the parties arrived in a new city, Holmes would tell Carrie that her husband had just skipped town and had left instructions to meet him somewhere else. As time went on, they kept losing members.

“Howard is not with us,” Alice wrote in an undelivered letter to her mother soon after reaching Detroit. It’s unclear what H. H. Holmes had told the children to stop them from questioning their brother’s absence, but they seemed to be unconcerned.

Instead, Alice complained about the increasing cold, her homesickness, and how much she wished to see her mother and baby brother. What she could not have known was that her mother, baby Wharton, and Dessie were staying three blocks from their hotel in the same city.

The girls were last seen in Toronto.

ClickAmericanaCarrie Pitezel sent her children ahead of her in the belief that they were joining their father, but they were instead being killed by H. H. Holmes to cover up the murder of Ben Pitezel.

Carrie Pitezel and her group eventually arrived in Vermont on Holmes’ instructions. After repeatedly attempting to have Carrie send him her other children or move to another city, Holmes finally visited in person.

When this proximity did not improve his persuasion, he descended into the basement where he did a bit of digging before leaving. Later, Carrie Pitezel found a note telling her to go down there.

When she did, she nearly avoided a hole that had been dug down there with a precariously placed bottle of nitroglycerine. Later, she would come to believe this was Holmes’ attempt to kill her as well.

Although Holmes was by that point quite paranoid about pursuers, he did not realize that the Fidelity Mutual Insurance company had been following him and the Pitezels for weeks. While he was out of their jurisdiction in Canada, by returning to the U.S., he had opened himself up to arrest.

The Arrest Of H. H. Holmes

Chicago History MuseumH. H. Holmes shown in the mid to late 1890s.

It’s possible that H. H. Holmes suspected something was coming just before his capture. For unclear reasons, after visiting Carrie Pitezel, he returned to Gilmanton, New Hampshire and reunited with his wife, Clara, his now 15-year-old son Robert, and his parents.

He explained that a terrible accident eight years earlier had given him amnesia. In the hospital, he received the name “H. H. Holmes” and had eventually fallen in love with and then married his nurse Georgiana before remembering his life as Herman W. Mudgett.

Although this was perhaps his worst tall tale in a long line of them, for some reason, they believed him. It seems likely that, no matter the improbability of the story, Holmes’ old loved ones wanted to believe this more comforting version of events.

But Holmes left not long after telling this tale to pursue business in Boston, though he promised he would return soon to pick up his life where he left off. He may have even meant it, for once, but Holmes would never return to New Hampshire again.

On November 17, Holmes was arrested in Boston, initially charged with horse theft stemming from accusations back in Texas. Then the charges quickly escalated to insurance fraud, to which Holmes confessed.

In his changing stories, Holmes said that he had intended to defraud the insurance company by passing off a cadaver as Ben Pitezel, but his partner killed himself before they could proceed. He said he then staged the scene to look like an accident to try and secure the money for his family, since Fidelity was under no obligation to pay in the event of suicide.

Wikimedia CommonsPhiladelphia Police Detective Frank Geyer, the man who took down H. H. Holmes.

He also claimed that the Pitezel children were alive and well, traveling with his old friend Minnie Williams, who may have taken them to London.

Carrie Pitezel was also arrested for her part in the fraud scheme; she did, after all, know about the “plan.”

While the two sat in prison in Philadelphia, police back in Chicago started searching H. H. Holmes’ Englewood building, and in Indianapolis, Philadelphia Police Detective Frank Geyer set off in pursuit of the Pitezel children.

All The Skeletons Unearthed

In a tale of two very different investigations, Geyer and an Inspector Gary from Fidelity Mutual checked hotel records and spoke to boarding house proprietors and renters who might have seen a group matching the description of H. H. Holmes and the children.

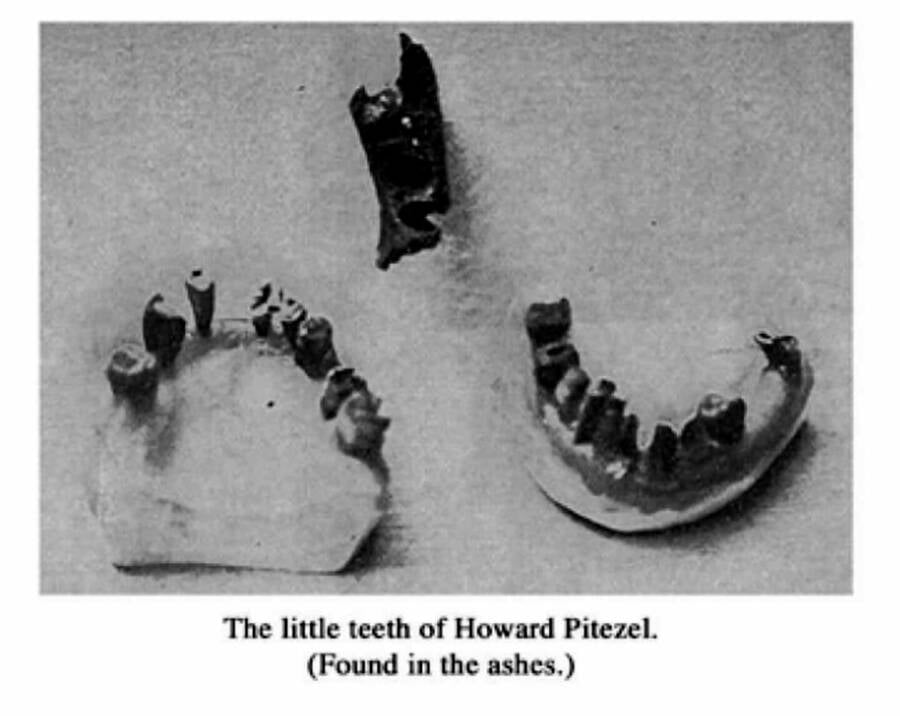

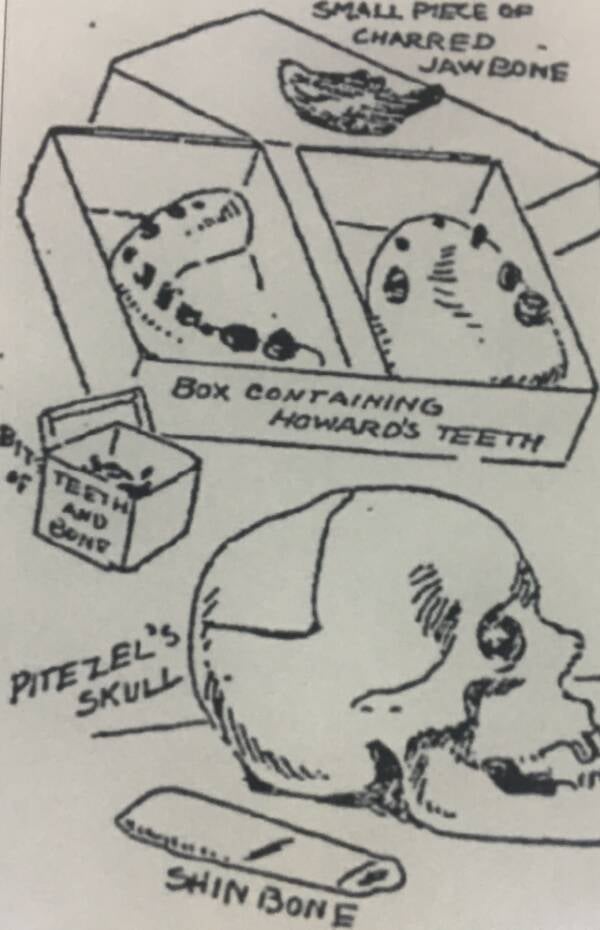

MurderpediaThe jaw bones and teeth of Howard Pitezel, discovered after H. H. Holmes’ arrest.

In Englewood, the Chicago police and dozens of reporters flooded into Holmes’ basement, accidentally causing an explosion when one worker’s candle set off fumes from an old fuel tank.

Geyer and Gary then tracked down a house Holmes had rented in Toronto. Upon entering the basement, they discovered a soft patch of earth on the dirt floor and started digging.

At the bottom of the shallow pit was a trunk that matched Carrie Pitezel’s description of the one she’d packed before the children had left St. Louis. Inside were the naked, rotting corpses of Alice and Nellie Pitezel.

When Holmes heard of the discovery, he is supposed to have said, “Well I suppose they’ll hang me for this.”

In Chicago, newly invigorated police and reporters began discovering all manner of incredible things while searching H. H. Holmes’ basement.

A tank of strange chemicals — later proved to be crude gasoline — was clearly a vat for stripping the flesh from skeletons, they said, while the strange furnace with its molding kiln surely must have been a crematorium. A scratched-up bench with some stains became a dissection table and a stained piece of rope found in Patrick Quinlan’s toolbox was obviously a noose used to hang victims in the dummy elevator shaft — regardless of Quinlan’s insistence that there was nothing sinister about it.

Public DomainNewspaper illustrator’s depiction of Holmes murdering Alice and Nelly Pitezel. Circa 1890s.

This isn’t to say that the investigation found nothing. Digging down into the basement floor eventually did uncover a stash of human bones preserved with quicklime.

They probably belonged to a child of about eight to 10 years old, investigators determined, but they had decayed so badly it was hard to identify them further.

Considering that this was the age of the missing Pearl Conner, investigators initially felt certain that they had found evidence against Holmes that would stick, though he claimed there was an innocent explanation: He had simply buried a rotting cadaver.

Meanwhile, a review of the contents of the basement stove uncovered bits of fabric and a watch chain, the latter of which was identified as having belonged to Minnie Williams.

Also in the stove, investigators found what were believed to be heavily-burnt human bones, but upon inspection were bits of fired clay and the remnants of turkey.

But regardless of what the truth was, the fantastical stories quickly took hold and didn’t let go.

Chicago lost its collective mind. Suddenly, dozens of people claimed they had either worked for Holmes, been approached by him to take out life insurance, or narrowly avoided death during stays at the Wallace Street building.

In one of the more striking examples, a man named Myron Chappell told police he had worked with Holmes articulating skeletons for sale to medical schools, strongly implying that he had helped dispose of all the supposed bodies.

Although often repeated as truth today, this story quickly fell apart back in 1895.

According to Chappell’s own son, his father was drunk and insane, but the Chicago police department dismissed such concerns and took the testimony seriously. And when it came out that Chappell was in fact lying, police were so embarrassed by this and other setbacks, they stopped interviewing further witnesses or investigating other sites where H. H. Holmes may have operated.

ClickAmericanaA 1937 newspaper illustration of what the H. H. Holmes crime scene investigation may have looked like.

In fact, in Chicago, the police never found enough evidence to charge Holmes in any crime despite searching the “castle” from top to bottom. In Ohio, however, Geyer and Gary finally found something substantial in their search for Howard Pitezel.

One neighbor recalled seeing a moving truck arrive at the vacant house next door occupied by a boy, a man, and an enormous stove. After she asked their neighbors what the new arrivals could possibly want with such a large oven, Holmes arrived at her front door to say he had decided not to take the house after all and that she could keep the stove if she wanted it.

Apparently suspicious of his neighbor’s attention, Holmes had abandoned his plan in Ohio. In Indianapolis, he had run into no such problems.

After locating the house Holmes had rented there, Geyer and Gary discovered that Holmes had had an identical stove installed during his brief stay. Inspecting the inside, they found scraps of clothing, burned photographs, several human teeth, and the top of a skull belonging to a pre-pubescent boy.

Public DomainNewspaper sketch of Ben Pitezel’s skull and Howard Pitezel’s skull fragments, kept in a prosecutor’s office.

These fragments would join Ben Pitezel’s skull in a box beneath the desk of Holmes’ lead prosecutor.

With no doubt that H. H. Holmes had murdered the three Pitezel children, his trial took place in Philadelphia.

Executing A Boogeyman

From prison, H. H. Holmes had written and published his memoir, Holmes’ Own Story, through outside agents in the attempt to garner sympathy and aid in his defense. While this and his newfound infamy in the press made jury selection more difficult, Holmes’ case was further compromised when the judge ruled that his trial would start as soon as possible.

MurderpediaH. H. Holmes wrote his own account of the murders in an attempt to garner support during his trial.

The prosecution had spent the better part of a year gathering witnesses from around the country, but the defense would have less than a month to prepare.

To make matters worse, his lawyers soon quit and Holmes agreed to act as his own attorney. But much to the amazement of court attendees, he was rather good at it, perhaps thanks to all the practice he’d had being sued in Chicago.

Although his attorneys would eventually return, several things nevertheless doomed Holmes. More damning even than the actual evidence marshaled against him were the emotional appeals played out before the jury.

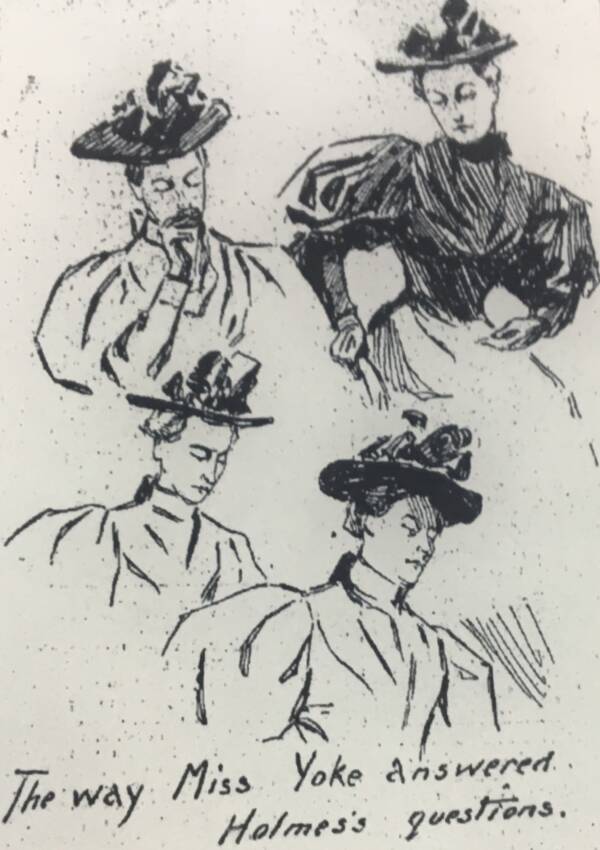

A weakened, traumatized Carrie Pitezel’s testimony, for example, brought the entire courtroom to tears. Georgiana Yoke, found by the judge to not be Holmes’ legal wife, coldly testified against him, causing H. H. Holmes to break down sobbing in open court before half-heartedly cross-examining her himself.

Public DomainGeorgiana Yoke sketched during her testimony by an artist from the New York World.

In one small victory, Holmes’ lawyers successfully argued that the case at hand centered only on the question of whether or not he had killed Ben Pitezel in Philadelphia, and not what had happened to the Pitezel children or anyone in Chicago.

Despite this, and the fact that the evidence of Ben Pitezel’s murder was circumstantial at best, the jury quickly convicted Holmes and he was soon sentenced to hang.

Although the story may have started in Chicago, William Randolph Hearst’s papers and others like the New York World wrote the H. H. Holmes legend as most of us know it today.

This largely began with the 1895 article, “The Castle of a Modern Bluebeard,” which included for the first time mentions of Holmes stalking his victims on the grounds of the World’s Fair, and also provided maps of each floor of the Englewood building, labeling rooms with names like “Torture Chamber.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe execution of H. H. Holmes as sketched by a newspaper artist.

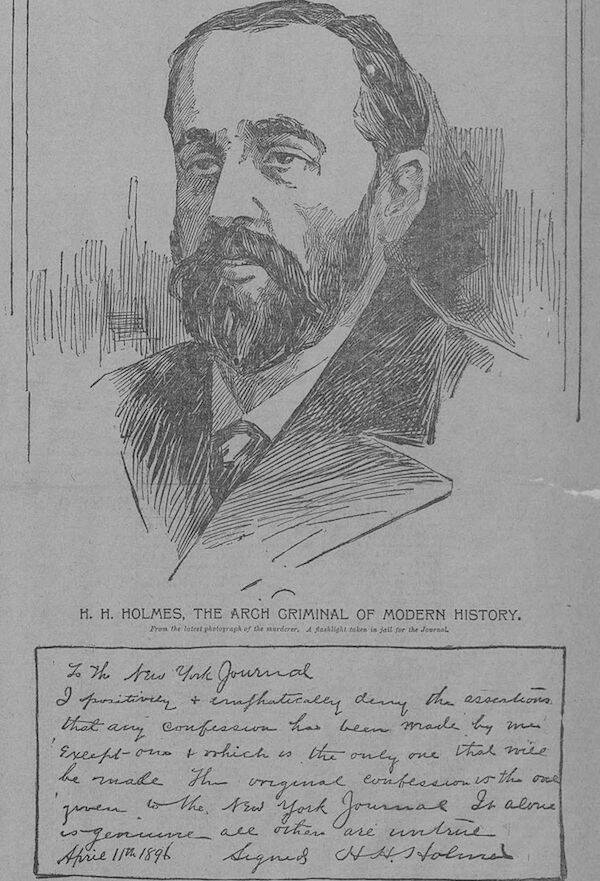

With this first article proving enormously popular and soon being reprinted around the country, the New York World built a relationship with Holmes, first allowing him to send them columns throughout his trial and then, after his conviction, paying as much as $7,500 for his full confession.

It seems likely that the World and the Philadelphia Inquirer split the cost to secure exclusive rights, but various “knock-off” versions appeared in the national press, including the account in the Philadelphia North American that added the now-infamous “quote,” “I was born with the devil in me.”

However, H. H. Holmes’ “confession” makes little sense. Although he claimed to kill 27 people, several of those he named were still alive — and he even got one of his purported victim’s names wrong.

It was suggested that Holmes was lying to secure money for his wives and children, but it is more likely that he was building a war chest in the hopes of filing an appeal.

Regardless, he quickly exhausted his options, including a failed insanity defense, and on May 7, 1896 — a little more than a week before his 35th birthday — he was hanged at Philadelphia’s Moyamensing Prison.

The Legend Of H. H. Holmes, The White City Devil

The story of H. H. Holmes lingered in the public consciousness for a while after his own demise but died off by the turn of the 20th century.

In the 1930s, following another World’s Fair in Chicago, one reporter recounted Holmes’ story, drawing heavily from the likes of Holmes’ own demonstrably false confession and the sensationalist reporting of the New York World.

Although the author mused that Holmes would only be in his 70s had he survived, he seemingly never realized how many other figures from the case were still available for interviewing, including police detectives who had worked the case, Holmes’ old tenants, and three of his wives. No such figures, people who could have shed light on what actually happened as opposed to parroting the myths, were ever interviewed.

In another inaccuracy from Devil in the White City, Larson claimed that the Wallace Street building burned to the ground in 1895, though it was actually still standing when this reporter was writing his article. Soon after, it was demolished to make way for a post office.

FlickrPost Office at 63rd and Wallace in Englewood, as it appears today, partially occupying the site of the so-called “murder castle.”

Then, in 1940, crime writer and lay historian Herbert Asbury got hold of the Holmes story in his book, Gem of the Prairie: An Informal History of the Chicago Underworld.

He too emphasized the 1893 World’s Fair as Holmes’ stalking ground, invented torture devices supposedly found in Holmes’ basement, and stated that hundreds of Chicago tourists had gone missing, many of whom stayed at Holmes’ World’s Fair hotel.

In the absence of more reliable records, the Asbury account and the New York World report became the building blocks for the modern Holmes legend.

Over the course of the 20th century, that legend evolved with the modern understanding of psychopathy, leading to the description of Holmes as a psychosexually motivated serial killer.

Authors like Larson continue to speculate about whether he had tortured animals as a child. In fact, Holmes notably loved animals, even raising a chicken in his prison cell while awaiting trial and execution.

In light of the actual facts, how much of the H. H. Holmes legend truly holds up?

Given the absence of any other suspects, it seems certain that Holmes killed Ben Pitezel and his three children, even if he denied it on the scaffold. Holmes admitted to killing Julia by accident in a botched abortion before murdering her daughter Pearl to cover up the first crime.

How exactly he killed these people is uncertain. Julia and Pearl’s bodies were never definitively identified. Bottles of cyanide and wolfsbane were found at the Indianapolis property where Howard Pitizel’s remains were discovered.

Public DomainNewspaper illustration of Holmes’ victims, including the fictional “Ms. Emily Van Tassel”. Circa 1890s.

And, although it is often claimed that Holmes suffocated Nelly and Alice by running a pipe from the gas line into the sealed trunk, the Toronto house they were buried under was not outfitted with gas.

But, apart from the confession, Holmes never admitted to killing Minnie or Nannie Williams or Emeline Cigrand, and police never even proved the three were dead.

Apart from Minnie’s watch chain and the story of the heavy trunk, the best evidence that could be provided on these points was the supposed footprint located inside the third-floor vault. Seemingly left by someone struggling and kicking to avoid suffocating, this print has provided fodder for many imaginations and is given a whole scene of its own in Devil in the White City.

While various authors have concluded that this print was left by either Nannie or Emeline in their final moments, Emeline had already gone missing before the vault was installed and Holmes left for Texas only three weeks after putting it in.

To make matters worse, many, like building resident Henry Darrow — who turned the “castle” into a dime museum for curious Chicagoans — admitted that they could not see this footprint at all. In all likelihood, it was an optical illusion if it ever actually existed at all.

Wikimedia CommonsHolmes, with prison beard, depicted alongside one of the reprinted versions of his confession. April 1896.

While Occam’s razor would suggest that Holmes probably killed Cigrand and the Williams sisters, the only murders we can be more or less certain of are the Conners and the Pitezels.

With that in mind, the psychopath described by the White City Devil myth seems misplaced, leaving us instead with a very different sort of criminal psychology more in step with modern notions about depraved killers and their twisted motives.

In fact, none of the H. H. Holmes murders were crimes of passion at all.

Instead, they were crimes of convenience and desperation, born of Holmes’ desire to remove witnesses and anyone who knew too much about what he had been up to — which, of course, consisted of crimes like fraud and forgery. The fact he likely tried to kill Mrs. Pitezel with nitroglycerine to silence her as well only lends more support to this theory.

This leaves us, then, with a final uncomfortable question.

Which is worse: Is H. H. Holmes the monster of our collective imagination who clinically murdered hundreds for his own amusement, or is he the kind of devil who murders children and tries to kill entire families to cover up for something as banal as insurance fraud?

For more on the legend of H. H. Holmes, take a look inside the White City Devil’s so-called “murder castle”. Then, discover the theory stating that H. H. Holmes was also Jack the Ripper.