The man's body featured chilling postmortem alterations, including dislocated legs and a twisted torso, in order to prevent him from rising from the dead.

Milica NikolićBones of the unearthed “vampire” found at the Rašaška archaeological site, south of the Croatian capital of Zagreb.

Archaeologists examining a grave site in Croatia recently uncovered disturbing evidence of a “vampire” burial. Investigations revealed that the remains of the deceased had been deliberately moved, with two stones placed near the head and feet — a practice that was likely intended to prevent the man from rising from the grave.

The grave, believed to date back to sometime between the 13th and 16th centuries, was discovered last year at the archaeological site of Rašaška (or Račeša), an estate with links to the Templars and the Order of the Knights of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem.

The findings were published in a report titled Military Orders and Their Heritage, released ahead of a recent archaeological conference in Zagreb.

A Strange Grave Uncovered In Rašaška, Croatia Leaves Researchers Intrigued

Milica NikolićThe positioning of the remains suggests an atypical burial reserved for “problematic” members of society.

While examining the archaeological site in late 2024, researchers came across what could only be described as a strange burial. Whereas a typical medieval burial in the region would see the dead laid to rest on their backs, with arms at their sides or folded over their chests, this particular grave contained remains that had clearly been adjusted postmortem in some unsettling ways.

“What caught our attention during the excavation was the unusual position of the person,” the authors wrote in the study. The deceased’s chest was turned face down, their head was separated from the neck and buried nearly a foot away, and two large stones had been placed between the legs and under the head.

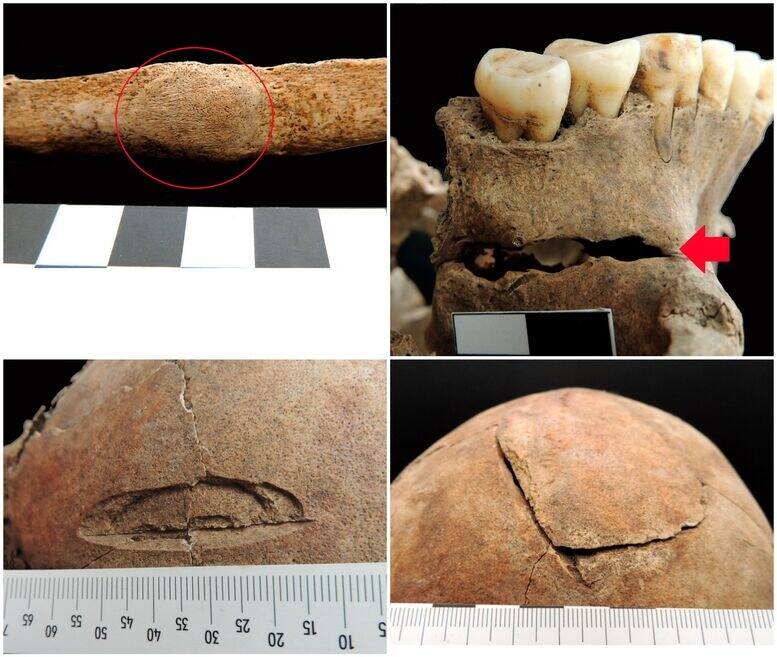

To piece together the reasons behind the peculiarities of this burial, Dr. Nataša Šarkić conducted an anthropological analysis on the remains. Initial observations noted that the remains had belonged to a middle-aged man, either in his 40s or 50s, whose body showed clear signs of heavy physical labor, particularly on their vertebrae and lower half. Šarkić also observed injuries on the skull that “were the result of interpersonal violence, and they had fatal consequences,” as the Serbian-language site Sve o Arheologiji (“All About Archaeology”) reported.

Nataša Šarkić The emptied “vampire” grave, with the large stones still in position.

Šarkić found that the body had initially been buried in a more traditional fashion, then later moved and placed in the strange manner in which it was found — a method that Šarkić said “was always reserved only for those who were in some way unfit in that society. That is, this can be considered a form of punishment.”

But why would a person be punished like this postmortem? To answer that question, researchers noted the historical context of medieval European beliefs about death — specifically the widespread fear of “vampires.”

Evidence Of A “Vampire” Burial Illustrates Medieval Concerns About The Dead Rising From The Grave

Nataša Šarkić Damage to the skull and skeleton of the deceased “vampire.”

Based on their observations, researchers believe that the person buried at Rašaška may have been a soldier or knight of some kind, given the signs of violence on his remains. If not, however, then he may have been a “problematic” person in society, one who defied cultural norms.

That would explain why the remains were tampered with later on. Medieval Slavs believed that a person’s soul did not immediately pass on to the afterlife when the body died. Rather, they believed that the soul would only depart once the body had rotted away, 40 days later. If that person was a sinner or suffered a violent death, however, it was believed that their body would not decompose and instead rise from the grave as a vampire.

Cutting off the head and placing stones to weigh the body down are actions that align with other anti-vampire measures observed in burials from medieval Europe. In Poland, for instance, archaeologists have uncovered numerous vampire burials featuring remains found with sickles over their necks, locks on their toes, or heavy stones atop their bodies.

Nataša Šarkić The “vampire” skull with a pebble in its mouth.

“A characteristic of vampires is their near indestructibility, and thus precautions were taken to prevent the transformation of the recently deceased into vampires,” the study’s authors wrote. “The most common way to do this was to destroy the corpse of those thought to be most at risk of becoming a vampire, specifically by driving a stake through the corpse’s heart. Based on superstition, other methods were also viable, including: burning the corpse; beheading the corpse and then burying the head between the feet or legs, behind the buttocks, or away from the body.”

Researchers also noted that these burials were not limited exclusively to “sinners” or murder victims. Often, those buried in an atypical fashion simply did not fit into society for one reason or another, and that includes those who were disabled or diseased.

This discovery is a macabre illustration of the dark attitudes toward marginalized members of society during the Middle Ages, people whose differences sometimes resulted in them being labeled vampires, making it impossible for them to attain dignity in society even after death.

After reading about this medieval vampire grave in Croatia, learn about nine alleged real-life vampires throughout history. Then, learn about how Count Orlok helped transform the modern vampire myth.