Though Massachusetts pardoned most accused witches in 1957 and 2001, Elizabeth Johnson Jr.'s name was left off the list.

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of a young woman thought to have “witch’s marks.”

In 1693, 22-year-old Elizabeth Johnson Jr. of Andover, Massachusetts, was accused of being a witch. For centuries, that accusation stood. Now, a group of 13- and 14-year-olds want to make sure Johnson finally gets justice.

“To right a wrong, it’s worth doing,” said Carrie LaPierre, who introduced Johnson’s story to her eighth-grade civics class at North Andover Middle School.

After researching Johnson’s case, LaPierre’s students began pushing for a pardon. The state of Massachusetts had offered pardons to accused witches before, in 1957 and 2001, but Johnson’s name was left off the list. The students want to change that.

They enlisted the help of state senator Diana DiZoglio to help them in their efforts. DiZoglio, impressed and inspired by the students, introduced legislation to clear Johnson’s name. Her legislation would amend the 1957 law to include Johnson.

“Why Elizabeth was not exonerated is unclear but no action was ever taken on her behalf by the General Assembly or the courts,” DiZoglio explained.

“Possibly because she was neither a wife nor a mother, she was not considered worthy of having her name cleared. And because she never had children, there is no group of descendants acting on her behalf.”

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of the Salem witch trials.

Over 300 years ago, Johnson was swept up in the hysteria of the Salem witch trials. Between 1692 and 1693, people living in and near Salem accused each other of practicing the “Devil’s magic.”

Many of them were subjected to impossible-to-pass “witches tests.” These included swim tests (if the accused floated she was guilty; if she drowned she was innocent, though dead) and forced recitation of prayers.

Johnson, and 28 members of her family, were accused of practicing witchcraft during this time. Authorities often pointed the finger at people considered “different.” Since Johnson’s own grandfather described her as “simplish” at best, it’s possible she had an intellectual disability.

But in the end, Johnson got lucky. Although she confessed to being a witch and was sentenced to hang, Massachusetts governor William Phips threw out her conviction as the hysteria surrounding possible witches died down.

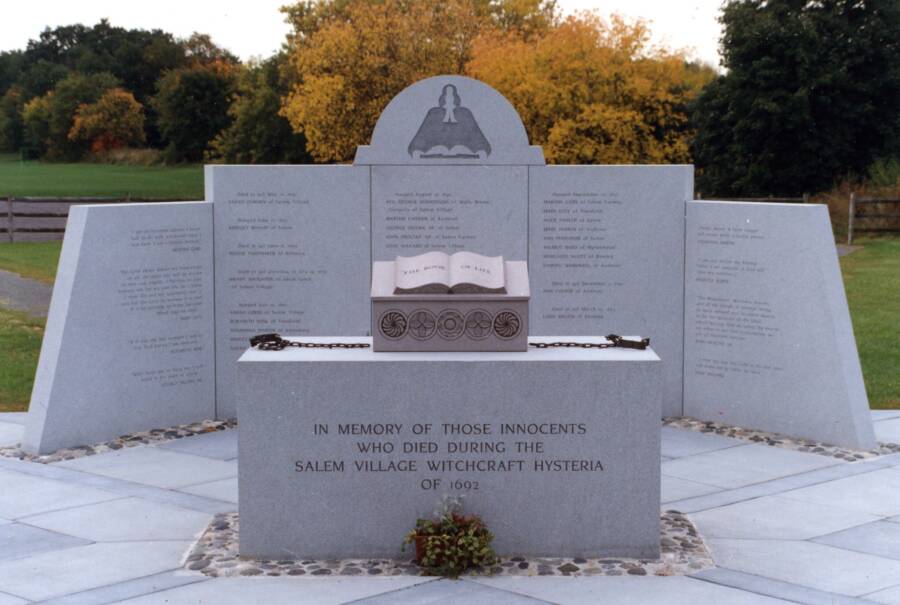

By the time the dust cleared, authorities had hanged 19 people for witchcraft and executed one man by crushing him with stones.

TwitterA memorial in Salem for those who died after being accused of witchcraft.

However, although authorities later admitted their wrongs and pardoned the accused witches, Johnson’s name has been stained by “witchcraft” for 328 years.

“It showed how superstitious people still were after the witch trials,” explained Artem Likhanov, a 14-year-old involved in the push to pardon Salem’s last witch.

“It’s not like after it ended people didn’t believe in witches anymore. They still thought she was a witch and they wouldn’t exonerate her.”

But, hopefully, the eighth-graders will change that. Though some were initially unenthusiastic about the project — with COVID-19 raging and the chaos surrounding the 2020 election they felt it lacked relevance. However, they soon became fired up in seeking justice for Johnson.

“They came around to the idea that it’s important that in some small way we could do this one thing,” LaPierre explained.

DiZoglio agrees. Though the pardon would be largely symbolic — Johnson is, after all, long dead — it would right a wrong, and bring justice to someone wrongly accused.

“It is important that we work to correct history,” DiZoglio noted.

“We will never be able to change what happened to these victims, but at the very least, we can set the record straight.”

After reading about Salem’s last witch and the push to pardon her, dive into the fascinating history of witches. Or, read about the Basque Country witch trials, which were much worse than Salem’s.