Though believers say that the prophet Moses, Paul the Apostle, and God Himself are the main authors who wrote the Bible, the historical evidence is more complicated.

Given its immense reach and historical influence, it’s a bit surprising how little we really know about the Bible’s origins. In fact, we have only scattered answers to the fascinating questions of who wrote the Bible and when.

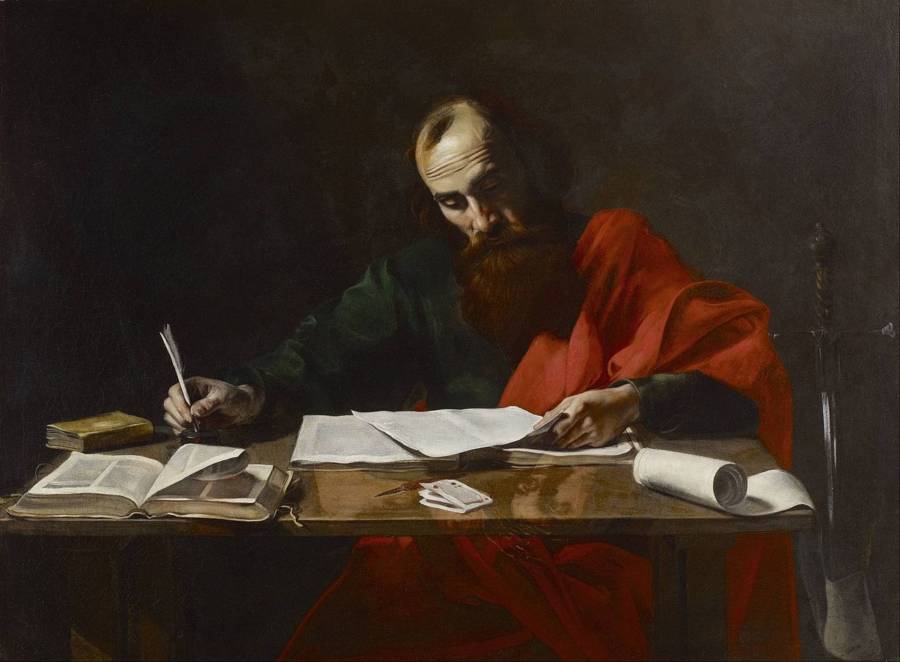

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of Paul the Apostle writing his epistles.

Experts aren’t completely without answers, however. Some books of the Bible were written in the clear light of history, and their authorship isn’t terribly controversial.

Other books can be reliably dated to a given period by either historical context clues — sort of the way no books written in the 1700s mention airplanes, for instance — and by their literary style, which develops over time.

Religious doctrine, meanwhile, holds that God himself is the author of or at least the inspiration for the entirety of the Bible, which was transcribed by a series of humble vessels. While the Pentateuch (the Old Testament) is credited to Moses and 13 of the New Testament’s books are attributed to Paul the Apostle, the full story of who wrote the Bible is much more complex.

Indeed, when digging into the actual historical evidence regarding who wrote the Bible, the story becomes longer and more complex than religious traditions let on.

- The Origins Of The Bible

- The Old Testament: Who Wrote It And When

- Who Wrote The Bible: The New Testament

The Origins Of The Bible

The Bible’s origins were not a specific moment in time but rather a long process that spanned more than a millennium from around 1200 B.C.E. to 100 C.E. In short, there’s no simple answer to the question of when the Bible was written.

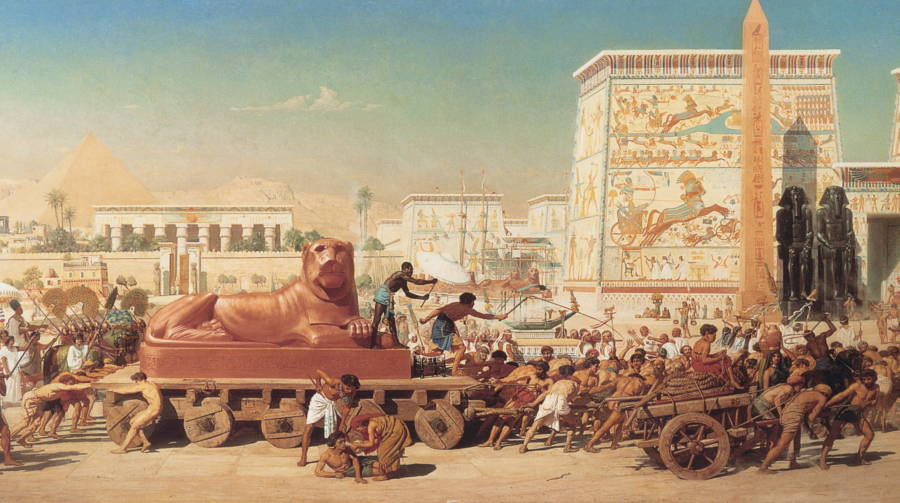

Its earliest texts arose from oral traditions within Hebrew communities, reflecting their experiences as nomadic tribes, slaves in Egypt, and eventually a settled nation in Canaan.

Historical Context Surrounding The Creation Of The Bible

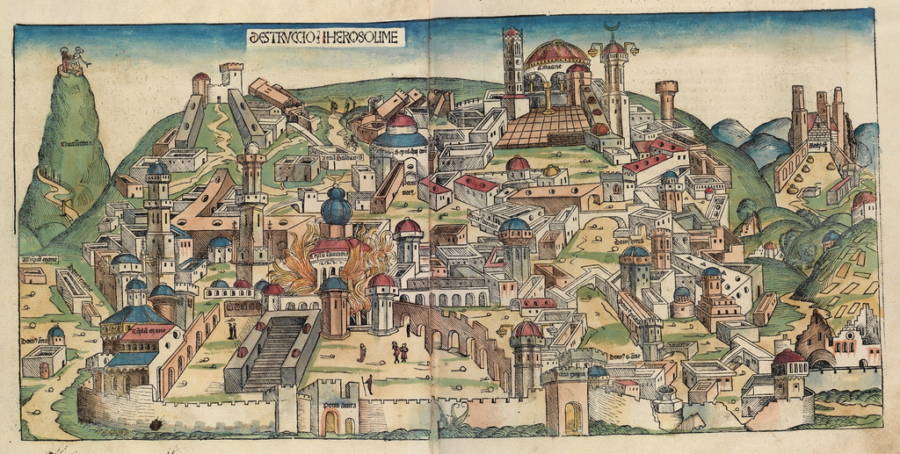

Wikimedia CommonsThe exile of the Jews from Canaan to Babylon in 597 B.C.E.

The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) developed in three main sections: the Torah, the Prophets, and the Writings. The Torah, or the Five Books of Moses, likely reached its final form during or after the Babylonian exile in the sixth century B.C.E., though it incorporates much older material.

The Prophets section includes both historical narratives and prophetic literature spanning several centuries. The Writings contain diverse materials like Psalms, Proverbs, and later works such as Daniel.

The Compilation Process: How The Bible Was Formed Over Time

The compilation of the Bible was gradual and complex. Jewish religious authorities didn’t formally canonize their scriptures until the Council of Jamnia around 90 C.E., though the core texts were widely accepted far earlier. This process essentially involved determining which texts were divinely inspired and authentically connected to their religious tradition.

The Christian Bible came about much later, incorporating the Hebrew scriptures as the Old Testament, and then adding the New Testament. Early Christian writings had circulated independently before later being collected and recognized as canonical. The New Testament’s final form wasn’t settled until the fourth century C.E., with various church councils debating which gospels, letters, and other writings to include.

Throughout the process, political upheavals, religious reforms, and theological debates influenced which texts survived and gained authority. In that way, the Bible represents not a single authored work but a carefully curated library reflecting centuries of religious thought and community experience. This also has the unfortunate effect of making it difficult to identify the specific people who helped to develop those ideas.

The Old Testament: Who Wrote It And When

Wikimedia CommonsMoses, widely known as one of the Bible’s main authors, as painted by Rembrandt.

According to both Jewish and Christian Dogma, the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy (the first five books of the Bible and the entirety of the Torah) were all written by Moses in about 1,300 B.C.E. There are a few issues with this, however, such as the lack of evidence that Moses ever existed and the fact that the end of Deuteronomy describes the “author” dying and being buried.

Scholars have developed their own take on who wrote the Bible’s first five books, mainly by using internal clues and writing style. Just as English speakers can roughly date a book that uses a lot of “thee’s” and “thou’s,” Bible scholars can contrast the styles of these early books to create profiles of the different authors.

Authorship And Composition Of The Old Testament

In each case, these writers are talked about as if they were a single person, but each author could just as easily be an entire school of people writing in a single style. These biblical “authors” include:

- E: “E” stands for Elohist, the name given to the author(s) who referred to God as “Elohim.” In addition to a fair bit of Exodus and a little bit of Numbers, the “E” author(s) are believed to be the ones who wrote the Bible’s first creation account in Genesis chapter one.

Interestingly, however, “Elohim” is plural, so chapter one originally stated that “Gods created the heavens and earth.” It’s believed that this hearkens back to a time when proto-Judaism was polytheistic, though it was almost certainly a one-deity religion by the 900s B.C.E., when “E” would have lived.

- J: “J” is believed to be the second author(s) of the first five books (much of Genesis and some of Exodus), including the creation account in Genesis chapter two (the detailed one where Adam is created first and there’s a serpent). This name comes from “Jahwe,” the German translation of “YHWH” or “Yahweh,” the name this author used for God.

At one time, J was thought to have lived close to the time of E, but there’s just no way that could be true. Some of the literary devices and turns of phrase that J uses could only have been picked up sometime after 600 B.C.E., during the Jewish captivity in Babylon.

For example, “Eve” first appears in J’s text when she is made from the rib of Adam. “Rib” is “ti” in Babylonian, and it’s associated with the goddess Tiamat, the mother deity. A lot of Babylonian mythology and astrology (including the stuff about Lucifer, the Morning Star) snuck into the Bible in this way via the captivity.

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of the destruction of Jerusalem under Babylonian rule.

- P: “P” stands for “Priestly,” and it almost certainly refers to a whole school of writers living in and around Jerusalem in the late sixth century B.C.E., immediately after the Babylonian captivity ended. These writers were effectively reinventing their peoples’ religion from fragmentary texts now lost.

P writers drafted almost all of the dietary and other kosher laws, emphasized the holiness of the Sabbath, wrote endlessly about Moses’ brother Aaron (the first priest in Jewish tradition) to the exclusion of Moses himself, and so on.

P seems to have written just a few verses of Genesis and Exodus, but virtually all of Leviticus and Numbers. P authors are distinguished from the other writers by their use of quite a lot of Aramaic words, mostly borrowed into Hebrew. In addition, some of the rules attributed to P are known to have been common among the Chaldeans of modern-day Iraq, whom the Hebrews must have known during their exile in Babylon, suggesting that the P texts were written after that period.

Wikimedia CommonsKing Josiah, ruler of Judah starting in 640 B.C.E.

- D: “D” is for “Deuteronomist,” which means: “guy who wrote Deuteronomy.” D was also, like the other four, originally attributed to Moses, but that’s only possible if Moses liked to write in the third person, could see the future, used language no one in his own time would have used, and knew where his own tomb would be (clearly, Moses was not who wrote the Bible at all).

D also takes little asides to indicate just how much time has passed between the events described and the time of his writing about them — “there were Canaanites in the land then,” “Israel has not had such a great prophet [as Moses] down to this very day” — once again disproving any notions that Moses was the one who wrote the Bible in any way.

Deuteronomy was actually written much later. The text first came to light in the tenth year of the reign of King Josiah of Judah, which was roughly 640 B.C.E. Josiah had inherited the throne from his father at age eight and ruled through the Prophet Jeremiah until he was of age.

Around 18, the King decided to seize full control of Judah, so he dispatched Jeremiah to the Assyrians with a mission to fetch home the remaining diaspora Hebrews. Then, he ordered a renovation of the Temple of Solomon, where Deuteronomy was supposedly found under the floor — or so Josiah’s story goes.

Purporting to be a book by Moses himself, this text was a near-perfect match for the cultural revolution that Josiah was leading at the time, suggesting that Josiah orchestrated this “discovery” to serve his own political and cultural ends.

The Historical Books Of The Old Testament

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of the story in which Joshua and Yahweh make the sun stand still during battle at Gibeon.

The next answers to the question of who wrote the Bible come from the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings, generally believed to have been written during the Babylonian captivity in the middle of the sixth century B.C.E. Traditionally believed to have been written by Joshua and Samuel themselves, they’re now often lumped in with Deuteronomy due to their similar style and language.

Nevertheless, there is a substantial gap between the “discovery” of Deuteronomy under Josiah in about 640 B.C.E. and the middle of the Babylonian captivity somewhere around 550 B.C.E. However, it’s possible that some of the youngest priests who were alive in the time of Josiah were still alive when Babylon hauled off the whole country as captives.

Whether it was these priests of the Deuteronomy era or their successors that wrote Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings, these texts represent a highly mythologized history of their newly dispossessed people thanks to the Babylonian captivity.

Wikimedia CommonsA rendering of the Jews forced into labor during their time in Egypt.

This history opens with the Hebrews getting a commission from God to leave their Egyptian captivity (which probably resonated with the contemporary readers who had the Babylonian captivity on their minds) and utterly dominate the Holy Land.

The next section covers the age of the great prophets, who were believed to be in daily contact with God, and who routinely humiliated the Canaanites’ deities with feats of strength and miracles.

Finally, the two books of Kings cover the “Golden Age” of Israel, under the kings Saul, David, and Solomon, centered around the tenth century B.C.E.

The intent of the authors here isn’t hard to parse: Throughout the books of Kings, the reader is assailed with endless warnings not to worship strange gods, or to take up the strangers’ ways — especially relevant for a people in the middle of the Babylonian captivity, freshly plunged into a foreign country and without a clear national identity of their own.

The Bible’s Prophetic Writings

Wikimedia CommonsThe prophet Isaiah, widely called one of the Bible’s authors.

The next texts to examine when investigating who wrote the Bible are those of the biblical prophets, an eclectic group who mostly traveled around the various Jewish communities to admonish people and lay curses and sometimes preach sermons about everybody’s shortcomings.

Some prophets lived way back before the “Golden Age” while others did their work during and after the Babylonian captivity. Later, many of books of the Bible attributed to these prophets were largely written by others and were fictionalized to the level of Aesop’s Fables by people living centuries after the events in the books were supposed to have happened, for example:

- Isaiah: Isaiah was one of the greater prophets of Israel, and the book of the Bible attributed to him is agreed to have been written in basically three parts: early, middle, and late.

Early, or “proto-” Isaiah texts may have been written close to the time when the man himself really lived, around the eighth century B.C.E., about the time when the Greeks were first writing down Homer’s stories. These writings run from chapters one to 39, and they’re all doom and judgment for sinful Israel.

When Israel actually did fall with the Babylonian conquest and captivity, the works attributed to Isaiah were dusted off and expanded into what’s now known as chapters 40-55 by the same people who wrote Deuteronomy and the historical texts. This part of the book is frankly the ravings of an outraged patriot about how all the lousy, savage foreigners will someday be made to pay for what they’ve done to Israel. This section is where the terms “voice in the wilderness” and “swords into ploughshares” come from.

Finally, the third part of the book of Isaiah was clearly written after the Babylonian captivity ended in 539 B.C.E. when the invading Persians permitted the Jews to return home. It’s not surprising then that his section of Isaiah is a burbling tribute to the Persian Cyrus the Great, who is identified as the Messiah himself for letting the Jews return to their home.

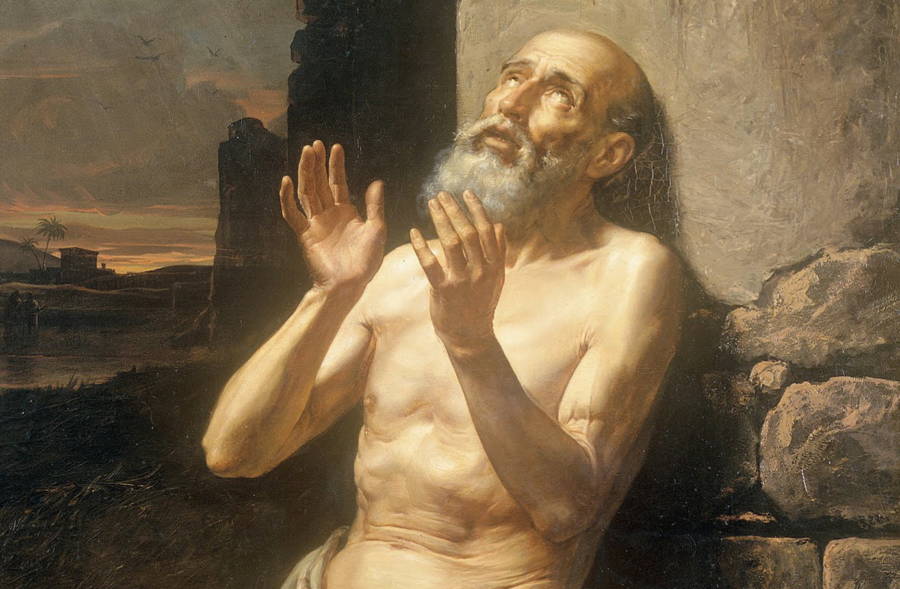

Wikimedia CommonsThe prophet Jeremiah, a nominal author of the Bible.

- Jeremiah: Jeremiah lived a century or so after Isaiah, immediately before the Babylonian captivity. The authorship of his book remains relatively unclear, even compared with other discussions as to who wrote the Bible.

He may have been one of the Deuteronomist writers, or he may have been one of the earliest “J” authors. His own book may have been written by him, or by a man named Baruch ben Neriah, whom he mentions as one of his scribes. Either way, the book of Jeremiah has a very similar style to Kings, and so it’s possible that either Jeremiah or Baruch simply wrote them all.

- Ezekiel: Ezekiel ben-Buzi was a priesthood member living in Babylon itself during the captivity.

There’s no way he wrote the whole book of Ezekiel himself, given the stylistic differences from one part to the next, but he may have written some. His students/acolytes/junior assistants may have written the rest. These also might have been the writers who survived Ezekiel to draft the P texts after the captivity.

History Of The Scripture’s Wisdom Literature

Wikimedia CommonsJob, the man at the center of one of the Bible’s most enduring stories.

The next section of the Bible — and the next investigation into who wrote the Bible — deals with what’s known as the wisdom literature. These books are the finished product of nearly a thousand years of development and heavy editing.

Unlike the histories, which are theoretically non-fiction accounts of stuff that happened, wisdom literature has been redacted over the centuries with an extremely casual attitude that has made it hard to pin down any single book to any single author. Some patterns, however, have emerged:

- Job: The book of Job is actually two scripts. In the middle, it’s a very ancient epic poem, like the E text. These two texts may be the oldest writings in the Bible.

On either side of that epic poem in the middle of Job are much more recent writings. It’s as if Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales were to be reissued today with an introduction and epilogue by Stephen King as if the whole thing were one long text.

Section one of Job contains a very modern narrative of setup and exposition, which was typical of the Western tradition and indicates that this part was written after Alexander the Great swept over Judah in 332 B.C.E. The happy ending of Job is also very much in this tradition.

Between these two sections, the list of misfortunes that Job endures, and his tumultuous confrontation with God, are written in a style that would have been around eight or nine centuries old when the beginning and ending were written.

- Psalms/Proverbs: Like Job, Psalms and Proverbs are also cobbled together from both older and newer sources. For example, some Psalms are written as if there’s a reigning king on the throne in Jerusalem, while others directly mention the Babylonian captivity, during which time there was of course no king on the throne of Jerusalem. Proverbs was likewise continuously updated until about the mid-second century B.C.E.

Wikimedia CommonsA rendering of the Greeks taking Persia.

- Ptolemaic Period: The Ptolemaic period began with the Greek conquest of Persia in the late fourth century B.C.E. Before then, the Jewish people had been doing very well under the Persians, and they were not happy about the Greek takeover.

Their main objection seems to have been cultural: Within a few decades of the conquest, Jewish men were flagrantly adopting Greek culture by dressing in togas and drinking wine in public places. Women were even teaching Greek to their children and donations were way down at temple.

The writings from this time are of a high technical quality, partly thanks to the hated Greek influence, but they also tend to be melancholy, likewise due to the hated Greek influence. Books from this period include Ruth, Esther, Lamentations, Ezra, Nehemiah, Lamentations, and Ecclesiastes.

Who Wrote The Bible: The New Testament

Finally, the question of who wrote the Bible turns to the texts dealing with Jesus and beyond: the New Testament.

Formation And Canonization

Wikimedia CommonsA depiction of Jesus delivering the Sermon on the Mount.

In the second century B.C.E. with the Greeks still in power, Jerusalem was run by fully Hellenized kings who considered it their mission to erase Jewish identity with full assimilation.

To that end, King Antiochus Epiphanes had a Greek gymnasium built across the street from the Second Temple and made it a legal requirement for Jerusalem’s men to visit it at least once. The thought of stripping nude in a public place blew the minds of Jerusalem’s faithful Jews, and they rose in bloody revolt to stop it.

In time, Hellenistic rule fell apart in the area and was replaced by the Romans. It was during this time, early in the first century A.D., that one of the Jews from Nazareth inspired a new religion, one that saw itself as a continuation of Jewish tradition, but with scriptures of its own:

The Gospel Accounts Of Jesus’ Life

The first Gospel to be written may have been Mark, which then inspired Matthew and Luke (John differs from the others). Alternatively, all three may have been based on a now-lost older book known to scholars as Q. Whatever the case, evidence suggests that Acts seems to have been written at the same time (the end of the first century A.D.) and by the same author as Mark.

Wikimedia CommonsPaul the Apostle, often cited as a major answer to the question of who wrote the Bible.

Mark, the shortest Gospel written around 65 to 70 C.E., likely targets Gentile Christians in Rome during a period of persecution. The author presents Jesus as the suffering Son of God, emphasizing action over lengthy discourses.

Mark’s narrative moves rapidly, frequently using the word “immediately” to create urgency and momentum. The Gospel focuses on Jesus’ mighty works — healings, exorcisms, and miracles — that demonstrate divine power while gradually revealing his identity. It emphasizes the “messianic secret” where Jesus often commands silence about his identity, suggesting that true understanding comes only through witnessing his death and resurrection.

Luke’s Gospel, meanwhile, was written around a decade later and addresses a broader Gentile audience, particularly those of higher social status. The author, who was like a well-educated Gentile companion of Paul, presents Jesus as the universal savior of humanity. Luke emphasizes God’s concern for marginalized groups more than other Gospels, its narrative beginning with elaborate birth accounts and ending with Jesus’ ascension.

It is by far the most comprehensive biographical account of Jesus’ life, from his birth to his death. It also introduced parables like the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son, focusing on mercy and reconciliation. Women too play prominent roles throughout Luke’s narrative.

Matthew’s Gospel, written around the same time as Luke’s, focuses more on addressing a Jewish-Christian audience familiar with Hebrew scriptures. The author presents Jesus as the promised Messiah who fulfills Old Testament prophecies, opening with a genealogy tracing Jesus back to Abraham and David.

Wikimedia CommonsA 17th-century illustration of Matthew the Apostle.

Matthew effectively reframes Jesus as the new Moses, organizing his teaching into five major discourses that parallel the Torah’s structure. The Gospel of Matthew includes numerous quotations from Hebrew scriptures, often introduced by saying “this was to fulfill what was spoken by the prophet.” Here, Jesus is portrayed as both fulfilling and transcending Jewish law, addressing tensions that emerged between Jewish traditions and Christian practices, emphasizing the church’s mission to “all nations.”

The Gospel of John, on the other hand, is dramatically different from the Synoptic Gospels in style, emphasis, and theological emphasis. The author presents Jesus as the divine Word, or Logos, who became flesh, targeting both Jewish and Gentile audiences in a sophisticated theological treatise.

Rather than parables, John records lengthy discourses where Jesus reveals his identity through “I am” statements — “I am the bread of life,” “I am the light of the world.”

John’s perspective focuses on Jesus’ divine nature and pre-existence, opening with the cosmic proclamation that “the Word was God.” It largely hones in on miracles that reveal Jesus’ glory rather than demonstrating compassion for human need, and present sharp dualistic contrasts like light vs. darkness, truth vs. falsehood, or life vs. death. The author primarily wrote for Christians facing persecution and expulsion from Jewish communities, presenting Jesus as confident, commanding, and clearly divine.

The Epistles And The Writings Of Paul

The Epistles are a series of letters, written to various early congregations in the eastern Mediterranean, by a single individual. Saul of Tarsus famously converted after an encounter with Jesus on the road to Damascus, after which he changed his name to Paul and became the single most enthusiastic missionary of the new religion. Along the way to his eventual martyrdom, Paul wrote Epistles of James, Peter, Johns, and Jude.

Paul authored 13 letters, including Romans, Corinthians, Galatians, and others, addressing specific congregational issues while developing core Christian theology. His letters tackle problems like division, sexual immorality, disputes over Jewish law, and questions about Christ’s return. His writings established foundational concepts including justification by faith, the church as Christ’s body, and Christian freedom from Mosaic law.

The General Epistles addressed a broader Christian audience and included elements of practical Christian living, warnings against false prophets, and encouraged perseverance through persecution. These writings were among some of the earliest Christian theological writings and reveal the transformation of Christianity from a Jewish sect to a universal religion. Unlike the Gospels, the Epistles provide direct theological instruction, making them crucial for understanding early Christian thought.

Apocalyptic Literature: The Book Of Revelation

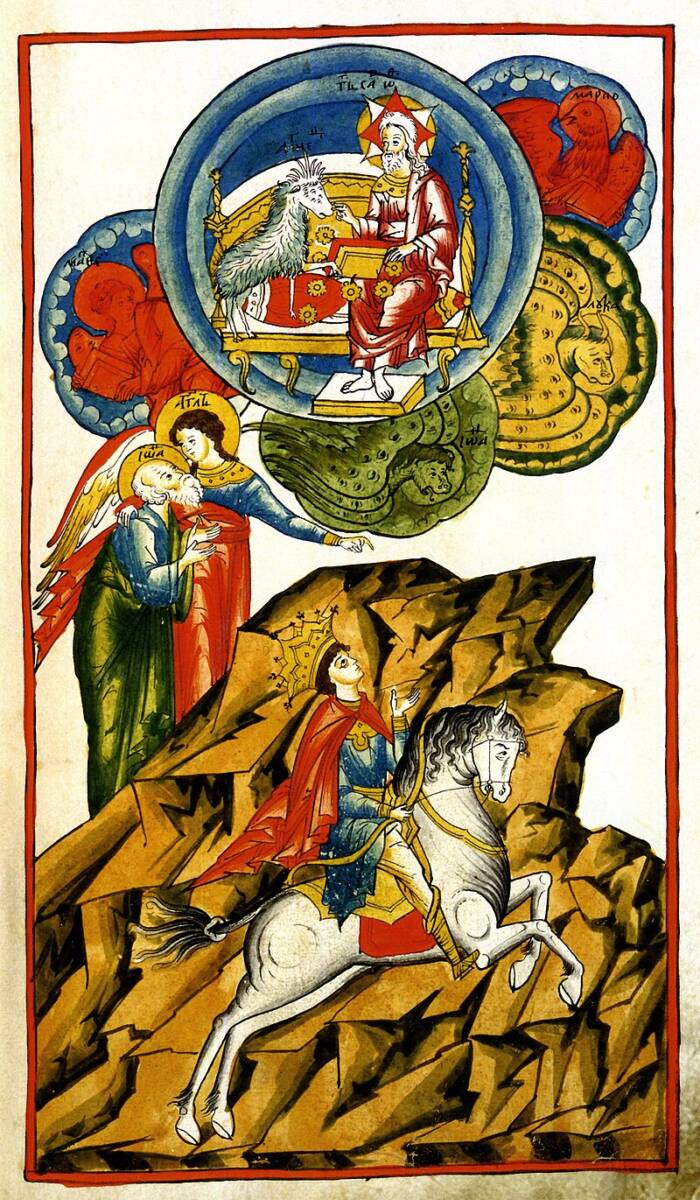

Wikimedia CommonsAmong the many striking and disturbing images in the Book of Revelation, the white horse remains one of the most well known.

The book of Revelation has traditionally been attributed to the Apostle John.

Unlike the other traditional attributions, this one wasn’t very far off in terms of actual historical authenticity, though this book was written a little late for someone who claimed to know Jesus personally. John, of Revelation fame, seems to have been a converted Jew who wrote his vision of the End Times on the Greek island of Patmos about 100 years after Jesus’ death at Golgotha.

Addressed to seven churches in Asia Minor during Roman persecution, Revelation uses symbolic imagery like beasts, seals, trumpets, and bowls to depict cosmic conflict between good and evil. The book presents Jesus as the victorious Lamb who defeats Satan and establishes God’s eternal kingdom.

Revelation’s highly symbolic language has generated diverse interpretations throughout history. Some view it as a prophecy about future end times, others as commentary on first-century Roman oppression, and others yet as timeless spiritual truths about God’s ultimate victory. The book offered hope to persecuted Christians, promising that despite their present suffering, God will judge evil and create “a new heaven and new earth.”

While the writings attributed to John actually do show some congruity between who wrote the Bible according to tradition and who wrote the Bible according to historical evidence, the question of Biblical authorship remains thorny, complex, and contested.

After this look at who wrote the Bible, read up on some of the most unusual religious rituals practiced around the world. Then, have a look at some of the strangest things that Scientologists actually believe.