On August 8, 1963, 15 men raided a postal train passing through a small English town, making off with the modern-day equivalent of $58 million in what’s known to this day as the Great Train Robbery.

During the early morning of August 8, 1963, a British postal train traveling from Scotland to England suddenly stopped at a red signal in a small village.

When the train’s co-engineer stepped out to investigate the issue, masked men attacked him and took control of the train. In total, 15 masked assailants cracked open the train’s car and stole £2.6 million — equivalent to $58 million today.

World History Archive/Alamy Stock PhotoThe train at the center of the Great Train Robbery at Railway Bridge in Ledburn, England.

The brash heist is now known as the Great Train Robbery, and it is still the largest train robbery in history.

The Night Of The Great Train Robbery

Around 3 a.m. on August 8, a British mail train traveling from Glasgow to London stopped at a red signal near Cheddington, England.

The co-engineer of the train, David Whitby, jumped from the lead car to investigate the signal that had delayed them. When he got close, he noticed a leather glove lying against the light. A six-volt battery also hung from the contraption.

Whitby went to make a call to the rail line to see what the issue was, but he noticed that someone had cut the phone lines. Confused at what he was seeing, Whitby started making his way back to the train but was quickly interrupted by a hand clamping down on his arm.

“If you shout, I will kill you,” a strange man told him, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Several masked men then emerged from the shadows, accompanying Whitby back to the lead car, where head engineer Jack Mills was waiting, unaware of the danger.

Thames Valley PolicePolice photograph of the glove used to cover the light stopping the train.

The masked men rushed into the car with a cudgel and began beating Mills over the head until he became unconscious.

The Great Train Robbery had begun.

How The Assailants Carried Out The Most Lucrative Robbery In History

After seizing control of the lead car, the men detached the first two cars from the 12-car train. Then, they realized they had a problem on their hands. The robber in their ranks assigned with learning to drive a train realized the mail locomotive was much more complex. They needed Mill.

Recognizing this issue, the men roused Mills from semi-consciousness and forced him to drive the train half a mile down the track as he bled. There, more masked men awaited the train’s arrival at Bridego Bridge in Ledburn.

More men emerged from the darkness, using iron tools to force the second car’s doors open. They subdued the staff inside and quickly formed a human chain, transporting bags of money from the train to their vehicles. In total, the men lugged 120 sacks of cash out of the train and into three vehicles: a military truck and two Range Rovers.

Thames Valley PoliceThe broken windows of the postal train.

The robbery of this train was no crime of opportunity. The weekend prior to the theft had been a bank holiday, resulting in a build-up of mail and cash-filled envelopes. The men knew that if they managed to pull it off, the robbery would be very lucrative.

Less than half an hour after stopping the train, the masked men made out with £2.6 million. Later, a guard patrolling the other 10 cars still stationary in Cheddington realized the gravity of the situation and called authorities.

For the authorities at Scotland Yard, the Great Train Robbery seemed like a nearly impossible crime to solve. After all, the men had worn masks, and very few witnesses were present. However, there was one clue as to where the thieves may have gone.

According to the British Transport Police, upon leaving the train, one masked man told the postal workers in the second car not to call police until 30 minutes after they’d left. This made authorities believe that the thieves likely had a local hideout.

The hunt was on.

A Gang Of Thieves On The Run

Thames Valley PoliceImage of the farmhouse the gang members hid in following the robbery.

Immediately following the Great Train Robbery, authorities began canvassing local neighborhoods, dredging up files on past offenders, and staking out several homes they deemed “suspicious.”

But this seemingly led nowhere.

Authorities started at square one, their first step being crime scene analysis. Given eyewitness testimony, authorities were confident that whoever planned this crime likely had an “insider” perspective of the mailing industry.

After all, the men knew when the train would come, which car contained the sacks of cash, how little security there was on the train, and the right place to stop the train.

While police worked on this theory, an important lead arose.

Days after the crime, a herdsman living roughly 20 miles from the scene telephoned the police after becoming suspicious of the nearby Leatherslade Farm. He’d seen men coming in and out of the home at bizarre hours following the robbery.

Police responded to this tip the next day and found a gold mine of clues in the farmhouse.

Even before they entered the home, authorities found 20 empty mailbags on the ground. The getaway vehicles involved in the crime sat covered in the yard.

Inside the home, police found sleeping bags, food provisions, and games. And while the robbers attempted to wipe their fingerprints from the home, police extracted several fingerprints from a game of Monopoly and a ketchup bottle.

With this new evidence, authorities slowly apprehended each robber one by one.

The Punishments For The Great Train Robbery

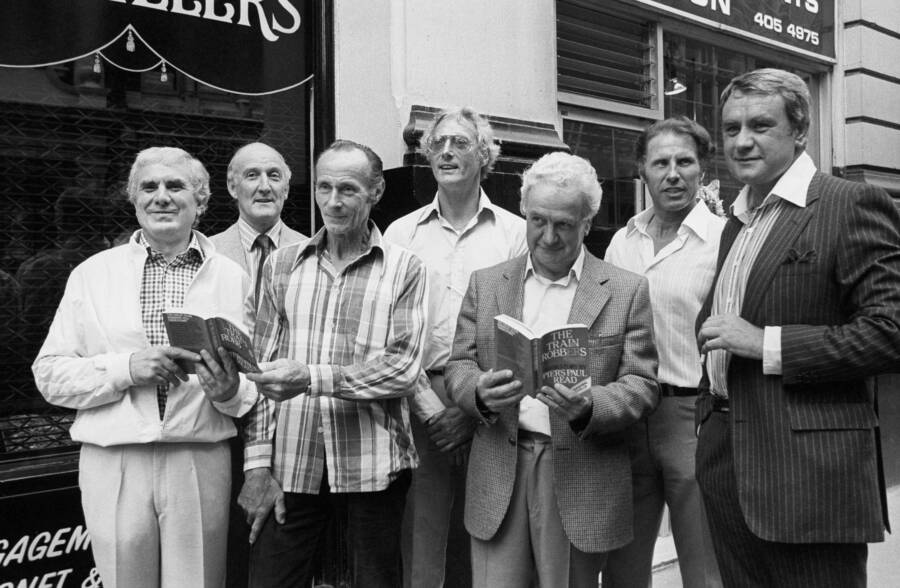

PA Images/Alamy Stock PhotoFrom left to right: Buster Edwards, Tommy Wisbey, Jim White, Bruce Reynolds, Roger Cordrey, Charles Wilson, and Jim Hussey, the seven men involved in the Great Train Robbery of 1963.

The first robber police apprehended for the Great Train Robbery was Roger Cordrey, a florist from Bournemouth. His landlord tipped off the police after he had given her rent payments three months in advance.

After police arrested Cordrey, they used knowledge of his associates to capture 12 more robbers: Gordon Goody, Charlie Wilson, Roy James, John Daly, Brian Field, Leonard Field, John Wheater, Ronnie Biggs, Tommy Wisbey, Jim Hussey, William Boal, and Bob Welch.

These men faced trial for the Great Train Robbery in 1964, with all but five receiving sentences of 30 years in prison. Interestingly, the court acquitted John Daly of the crime, citing insufficient evidence.

These harsh sentences led to prison escapes from both Charles Wilson and Ronny Biggs. In Wilson’s case, his associates helped him escape to Canada for a time before authorities located and extradited him back to England.

Ronny Biggs escaped prison in 1965 by scaling a wall and jumping into a furniture truck. He fled to France, then Australia, and finally Brazil. He managed to evade authorities until 2001 when, in poor health and aware he would be arrested, he came back to England for medical treatment and was imprisoned once more.

However, authorities did not arrest the ringleader of the operation until five years after the crime. Police arrested Bruce Reynolds, and a court sentenced him to ten years in prison. Authorities still do not know the identities of some members of the gang, including the postal service informant.

The conclusion of the Great Train Robbery of 1963 is a tragic one. Following the crime and incarcerations, several robbers went on to meet violent ends. According to Buckinghamshire Live, Buster Edwards committed suicide in the 1990s, Charles Wilson was shot to death by a hitman in Spain, and Brian Field died in a car crash with his wife and children.

For victims Jack Mills and David Whitby, the robbery also had lasting impacts. Mills never fully recovered from his injuries, suffering from headaches until his death in 1970.

David Whitby, traumatized by the events, died from a heart attack in 1972 at the age of 34.

And while the world’s largest train robbery is a fascinating story of robbers coming together to pull off a highly organized heist, one must remember the lasting impacts it had on the lives of those who experienced it.

After learning about the Great Train Robbery, discover the story of the Dalton Gang, a group of American outlaws in the West who robbed two banks at once. Then, read about the Lufthansa heist, when a group of mobsters stole $6 million from the JFK airport.