Lost continents continue to be discovered as the technology to study our ever-shifting tectonic plates grows more advanced.

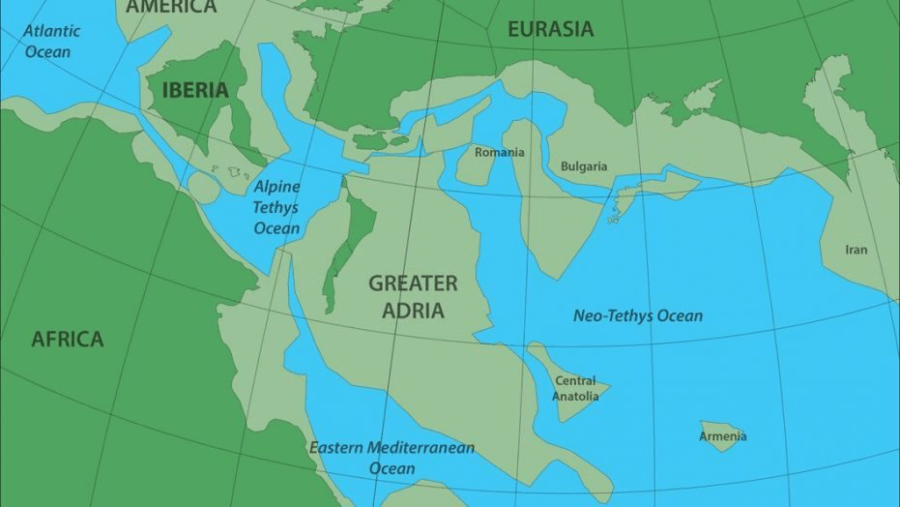

Douwe van HinsbergenGreater Adria, depicted as it’s theorized to have looked 140 million years ago. Dark green areas represent land above water, while light green areas are submerged.

Researchers have discovered a continent that’s been hidden beneath Southern Europe for around 140 million years. The landmass is as big as Greenland and formed many of Europe’s mountain ranges when it was buried.

According to CNN, a Utrecht University team found it while studying the Mediterranean region’s geology and how it evolved over time. Researching the evolution of mountain ranges allows experts to trace the evolution of continents.

“Most mountain chains that we investigated originated from a single continent that separated from North Africa more than 200 million years ago,” said Douwe van Hinsbergen, co-author of the study published in the Gondwana Research journal and a professor of global tectonics and paleography.

“The only remaining part of this continent is a strip that runs from Turin via the Adriatic Sea to the heel of the boot that forms Italy.”

The previously undiscovered landmass has since been dubbed Greater Adria for being located in a region geologists call Adria. Van Hinsbergen said countless people have already visited Greater Adria without an inkling.

“Forget Atlantis,” he said. “Without realizing it, vast numbers of tourists spend their holiday each year on the lost continent of Greater Adria.”

According to CBS News, the Dutch university team’s research suggests that a vast number of mountain ranges came about as a direct result of Greater Adria’s prehistoric split.

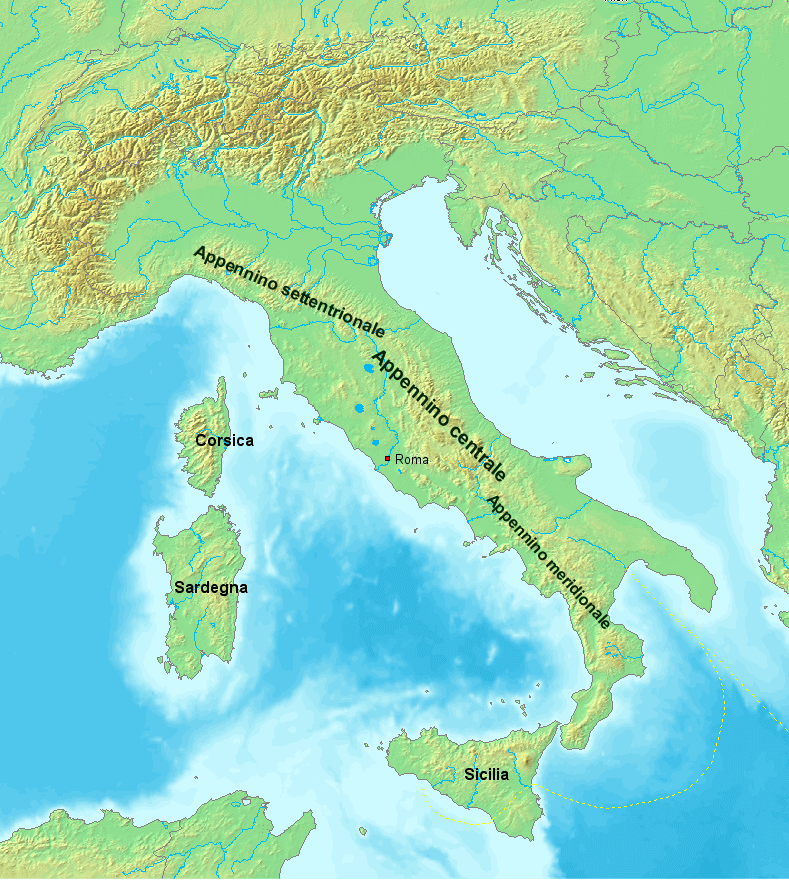

During the continent’s aquatic migration, much of the landmass was scraped off when it was forced under Southern Europe’s mantle. These removed masses then formed parts of the Alps, the Apennines, the Balkans, Greece, and Turkey.

Since plate tectonics work much differently in the Mediterranean than they do elsewhere, research was quite a challenge. In certain parts of the Earth, it’s believed tectonic plates don’t deform when moving alongside each other in places with substantial fault lines.

In Turkey and the Mediterranean, however, that theory doesn’t hold much weight.

“It is quite simply a geological mess,” said van Hinsbergen. “Everything is curved, broken and stacked. Compared to this, the Himalayas, for example, represent a rather simple system. There you can follow several large fault lines across a distance of more than 2,000 kilometers.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe Apennine mountains were formed when Greater Adria was forced beneath Southern Europe’s mantle. The Alps, the Balkans, Greece, and Turkey are believed to have resulted from this process as well.

Van Hinsbergen’s belief that the Mediterranean region is “geologically among the most complex” in the world is primarily the result of modern borders.

It “hosts more than 30 countries,” said Van Hinsbergen. “Each of these has its own geological survey, own maps and own ideas about the evolutionary history. Research often stops at the national borders.”

In order to reconstruct the evolution of these mountain ranges, Van Hinsbergen used software that allowed his team to look at tectonic plates across time.

“Our research provided a large number of insights, also about volcanism and earthquakes, that we are already applying elsewhere,” he said. “You can even predict, to a certain extent, what a given area will look like in the near future.”

They discovered that Greater Adria started forming into its own continent about 240 million years ago.

“From this mapping emerged the picture of Greater Adria, and several smaller continental blocks too, which now form parts of Romania, North Turkey or Armenia, for example,” said Van Hinsbergen.

Wikimedia CommonsAthanasius Kircher’s map of Atlantis from Mundus Subterraneus, 1669.

“The deformed remnants of the top few kilometers of the lost continent can still be seen in the mountain ranges,” said Van Hinsbergen.

“The rest of the piece of continental plate, which was about 100 kilometers thick, plunged under Southern Europe into the earth’s mantle, where we can still trace it with seismic waves up to a depth of 1,500 kilometers.”

Van Hinsbergen described the rocks scattered about by moving fault lines as “pieces of a broken plate,” according to LiveScience.

He called it a jigsaw puzzle — one he spent a decade putting back together. Though he’s moved on to similar work in the Pacific Ocean, he’s confident he’ll be back.

“I’ll probably return — probably in 5 or 10 years from now when a whole bunch of young students will demonstrate that parts are wrong,” he said. “Then I’ll come back and see if I can fix it.”

After learning about the lost continent of Greater Adria discovered buried beneath Southern Europe, read about ancient Pompeii porn holding the key to greater LGBT acceptance. Then, learn about the lost Mayan “megalopolis” being uncovered in the jungles of Guatemala.