Although John Nash's career in mathematics was hampered by a paranoid schizophrenia diagnosis in 1959, he went on to win a Nobel Prize in economics in 1994 for his work on game theory.

Wikimedia CommonsJohn Forbes Nash Jr. revolutionized game theory, but his struggle with paranoid schizophrenia caused a substantial strain to his personal life.

John Nash was a brilliant mathematician who is best known for his contributions to game theory. However, his academic career was curtailed due to his struggle with paranoid schizophrenia, which caused him to experience delusions and erratic behavior that led to multiple lengthy hospitalizations.

To many in the academic world, Nash’s story was a true tragedy. The long battle with schizophrenia very nearly derailed his career, and those in his personal life grappled with his sudden changes in behavior. He became convinced that he was being recruited by secret organizations or receiving coded messages from extraterrestrials. The mental illness forced him to leave his position at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and he lived a shadowy life as he withdrew from formal academic work.

However, despite the circumstances, Nash eventually prevailed. Without relying on medication, he slowly began to recover — something not typical of a person with his diagnosis. By the 1980s, Nash had reemerged on the academic scene with a clarity of mind astonishing to those who had witnessed his decline. His remarkable story was eventually adapted into the 2001 film A Beautiful Mind, based on the biography of the same name by Sylvia Nasar.

John Nash’s return to academia earned him several prestigious awards as well, including a Nobel Prize in economics, further emphasizing just how impressive his recovery was.

But tragically, just days after receiving one of the highest honors in mathematics, the Abel Prize, 86-year-old Nash was killed in a car accident. It was a shocking end to what Princeton University called a “tragic but meaningful” life.

John Nash’s Early Life And Career

John Forbes Nash Jr. was born on June 13, 1928, in Bluefield, West Virginia, a small industrial town nestled in the Appalachian Mountains. His father was an electrical engineer and his mother was a former schoolteacher. They were both well-educated and came from families that placed an emphasis on higher education, and they did the same for their son.

From a young age, Nash displayed signs of a remarkable intellectual capacity. While his parents encouraged his curiosity and bookishness, they were also concerned that he kept himself too isolated from other children in the neighborhood. His younger sister Martha, on the other hand, was a much more social child.

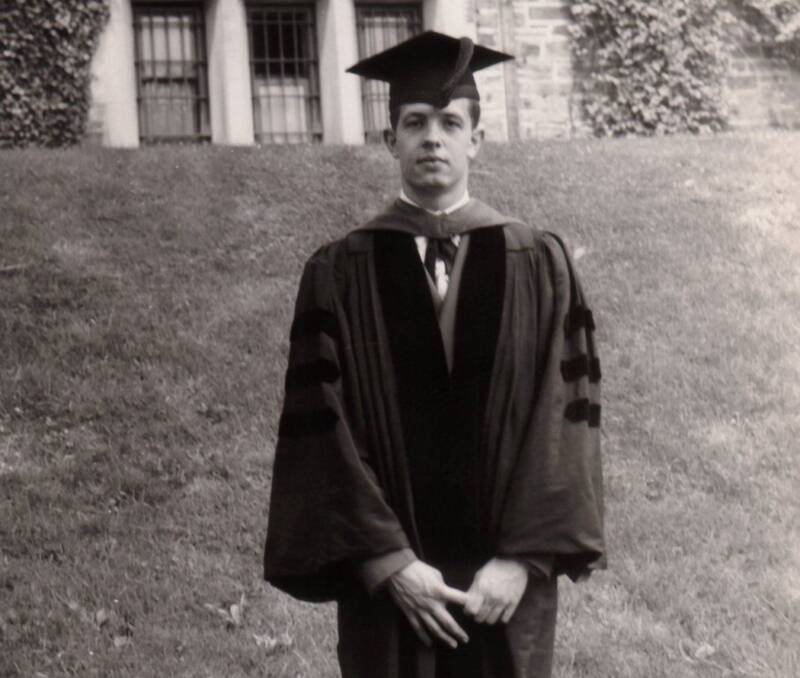

Martha Nash-Legg/Princeton University ArchiveJohn Nash at Princeton University.

“Johnny was always different,” Martha later recalled, according to Nasar’s biography. “[My parents] knew he was different. And they knew he was bright. He always wanted to do things his way. Mother insisted I do things for him, that I include him in my friendships. She wanted me to get him dates. She was right. But I wasn’t too keen on showing off my somewhat odd brother.”

Though he was no social butterfly, John Nash’s academic career left little doubt about his intelligence. At just 16 years old, he entered the Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University) to study chemical engineering. However, his prodigious talent for mathematics was impossible to ignore, and professors eventually convinced him to switch majors.

In 1948, he earned both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in math simultaneously — and then set his sights on Princeton University.

Princeton University And Early Mathematical Contributions

John Nash quickly established himself as an original thinker, though that came with its own eccentricities. For example, he famously wrote under “List of Interests” on his graduate school application simply: “Mathematics. Inventions.”

Martha Nash-LeggJohn Nash’s Princeton graduation photo.

In 1949, just one year into his graduate studies, Nash made a significant breakthrough in the mathematical field of real algebraic geometry. This eventually led him to draft a 27-page dissertation that introduced what would become known as the Nash Equilibrium, a concept that reshaped the field of game theory.

Up until then, game theory had largely been dominated by John von Neumann’s minimax theorem, focusing primarily on zero-sum games in which one player’s gain was another’s loss. Nash, however, extended this framework to non-cooperative games, demonstrating that even in competitive situations, there could exist a stable state where no player would benefit from changing their strategy unilaterally.

Put simply: If everyone in a situation is doing the best they can, given what everyone else is doing, nobody has an incentive to change. This is the core of the Nash Equilibrium.

Nash submitted this finalized theorem to the Annals of Mathematics in October 1951.

It was a deceptively simple idea, but it was incredibly versatile, too. The Nash Equilibrium could be applied to anything from economics to international relations to evolutionary biology and everyday decision-making. It revolutionized how scholars and policymakers thought about markets, negotiations, and behavior in complex systems.

Nash wasn’t a one-hit wonder, either. When he eventually began teaching at MIT in 1951, he continued to seek out high-profile mathematical problems to study. According to PBS, though, not everyone was fond of him. One woman who knew him at MIT called him “very brash, very boastful, very selfish, very egocentric. His colleagues did not like him especially, but they tolerated him because his mathematics was so brilliant.”

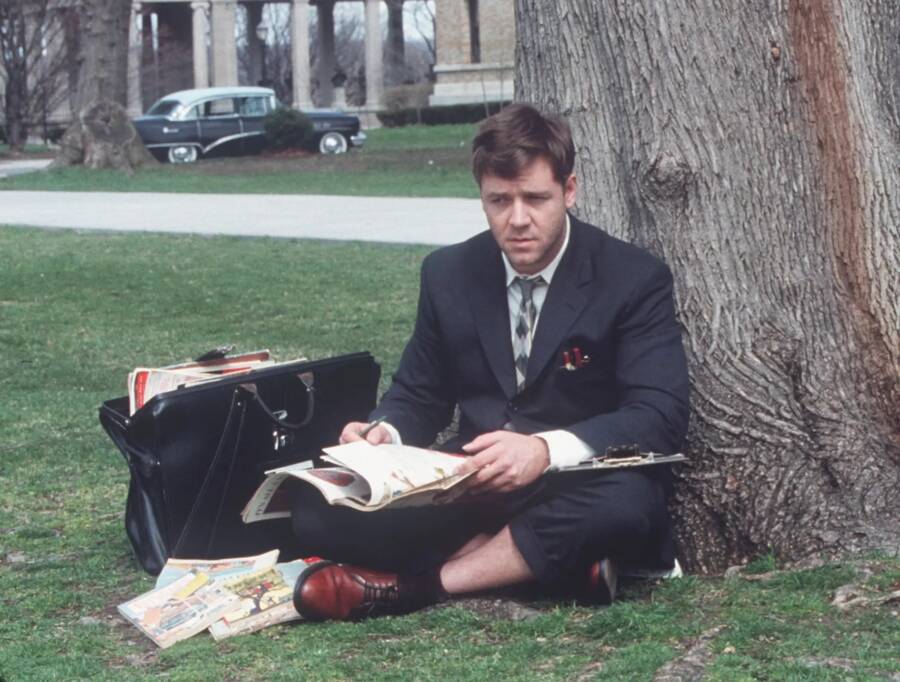

Universal PicturesRussell Crowe as John Nash in 2001’s A Beautiful Mind.

Throughout the rest of the 1950s, he made significant (though less publicly celebrated) contributions to differential geometry and partial differential equations, particularly through his work on isometric embedding theorems. By 1957, Nash was poised for a long and prosperous career. He had just married his wife, Alicia, and a year later, in July 1958, Fortune magazine named him one of the brightest mathematical minds in the world.

Still, Nash had yet to win any sort of coveted mathematical prize, and that weighed on him. Around the same time, Alicia became pregnant, and Nash began to worry he was already past his prime as an academic. Not to mention that he’d had another child with a woman named Eleanor Stier several years earlier, though he refused to put his name on the child’s birth certificate or provide financial support.

Then, in 1959, at the age of 30, Nash received a devastating diagnosis that would put his academic ascent on hold for more than 20 years.

John Nash’s Decades-Long Struggle With Schizophrenia

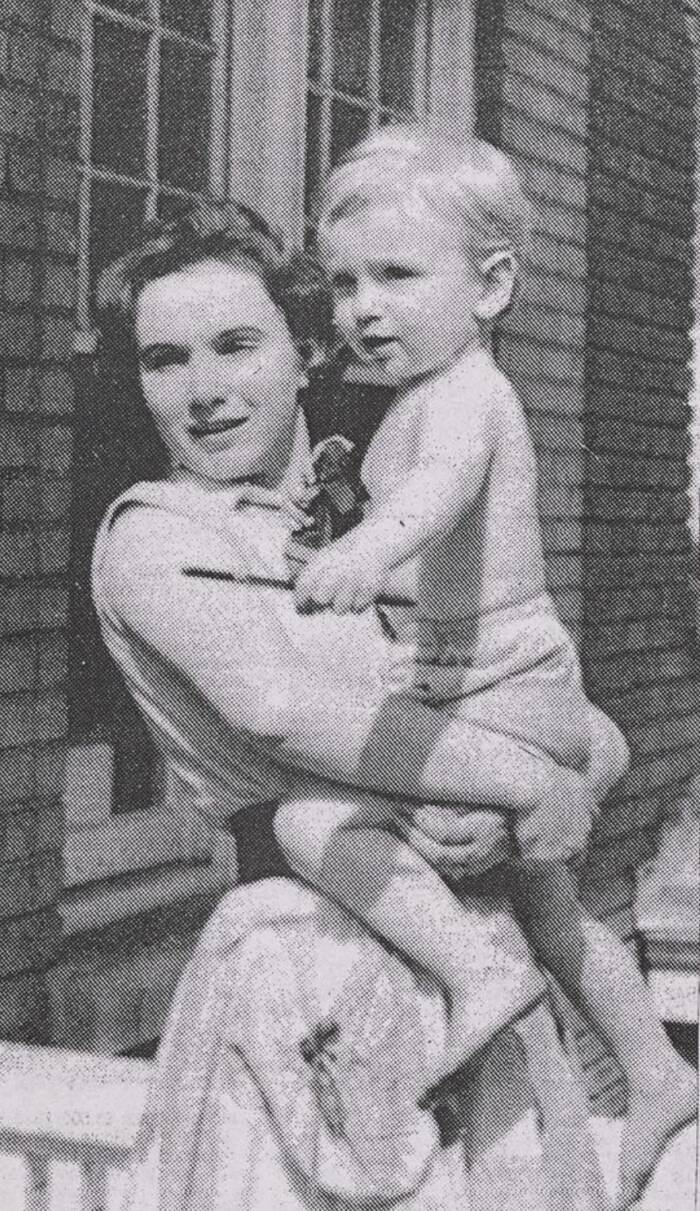

Martha Nash-LeggJohn and Alicia Nash after his schizophrenia diagnosis.

John Nash had become paranoid. Alicia would later describe him as erratic. He came to believe that any man wearing a red tie was part of some communist conspiracy against him and would send letters to embassies in Washington, D.C., to warn of an impending communist plot. He also claimed that extraterrestrials had been sending him coded messages.

But it was in early 1959, when Nash delivered an incomprehensible lecture at Columbia University, that his colleagues realized that something was seriously wrong.

Shortly after, in April, Nash was hospitalized for his condition for one month, during which doctors observed that he had been growing increasingly paranoid and suffering from delusions. Nash also started to become isolated, and in combination, these symptoms led to a diagnosis of schizophrenia. He was treated with antipsychotic medications and insulin shock therapy, but he later admitted that after leaving the hospital, he would only take his medication under pressure.

His mental illness worsened, and over the next nine years, it greatly impacted his career and personal relationships. In 1963, the strain of it caused him and Alicia to divorce. Alicia remained a supportive presence in his life, however, even allowing Nash to move back into her home in 1970 and referring to him as her “boarder.”

Martha Nash-Legg/Princeton University ArchivesAlica Nash with her son, John Charles Martin Nash, who would also later be diagnosed with schizophrenia.

“I spent times of the order of five to eight months in hospitals in New Jersey, always on an involuntary basis and always attempting a legal argument for release,” Nash wrote in 1994. “And it did happen that when I had been long enough hospitalized that I would finally renounce my delusional hypotheses and return to mathematical research.”

“But after my return to the dream-like delusional hypotheses in the later ’60s I became a person of delusionally influenced thinking but of relatively moderate behavior and thus tended to avoid hospitalization and the direct attention of psychiatrists,” Nash continued.

Then, shockingly, John Nash began to gradually recover. He stopped taking medication completely in the 1970s, and he was never again committed to a hospital. He lived at home and spent much of his free time wandering about the Princeton mathematics department, where he was known as the “Phantom of Fine Hall.”

“In those days, he was very present, but rarely said anything and just wandered benignly through Fine Hall. Nevertheless, we all knew that the mathematics he did was really spectacular,” said Princeton University’s David Gabai in an obituary for Nash. “It went beyond proving great results. He had a profound originality as if he somehow had insights into developing problems that no one had even thought about.”

Recovery, Later Years, And Death

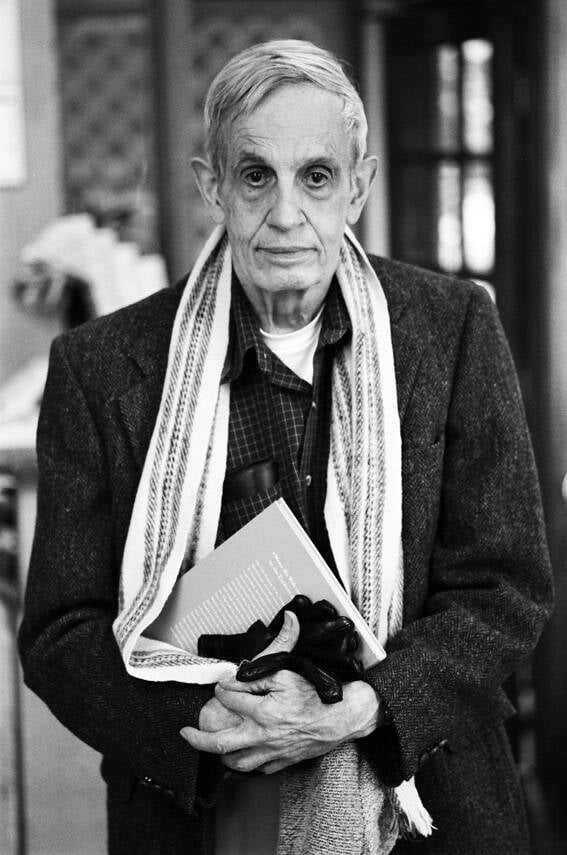

Denise Applewhite/Princeton University Office of CommunicationsJohn Nash in 1994, when he was awarded a Nobel Prize.

By the 1980s, John Nash had reclaimed his mind and begun to recover from his schizophrenia, a rare occurrence for someone with his diagnosis. He largely attributed his improvement to aging and a conscious decision to reject his delusional thoughts rather than medication.

“Thus further time passed,” he wrote. “Then gradually I began to intellectually reject some of the delusionally influenced lines of thinking which had been characteristic of my orientation. This began, most recognizably, with the rejection of politically oriented thinking as essentially a hopeless waste of intellectual effort. So at the present time I seem to be thinking rationally again in the style that is characteristic of scientists.”

Nash’s recovery challenged the understanding of schizophrenia at the time. Until then, it had been seen as a hopeless, degenerative condition, with most people believing that schizophrenics faced inevitable decline with no possibility of recovery. But when Nash returned to academic work and later received the Nobel Prize in economics in 1994, public perception about his condition began to shift.

It also emphasized the importance of support systems, as Alicia and the help she provided were instrumental in John’s recovery. Of course, that wasn’t the only reason he recovered. In fact, the conditions for his recovery became a point of fascination in the years that followed.

Wikimedia CommonsJohn Nash in 2011.

A Scientific American report from 2015 outlined a few of the key factors for Nash’s recovery, including the late onset of his symptoms, his age, his high intellectual functioning, and a supportive environment.

What Nash’s recovery showed was that schizophrenics are not doomed by their condition, and while not everyone with the diagnosis will recover, certain factors can contribute to an improvement. As difficult as it may be, providing support for schizophrenic individuals can be a major boon — and although John Nash still suffered from hallucinations later in life, his ability to “intellectually reject” them was a testament to his willpower.

Nash’s Nobel Prize receipt in 1994 was proof that recovery was possible, and when he was awarded the Abel Prize in 2015, there was no doubt about it. Unfortunately, on May 23, 2015, just days after receiving the accolade, John and Alicia Nash were ejected from a taxi after their driver lost control. Neither had been wearing a seatbelt, and they died in the accident.

John Nash was 86 years old.

After reading about John Nash and his remarkable recovery from schizophrenia, read about the tragic life of Kurt Gödel, the mathematician who starved himself out of paranoia. Then, learn about history’s 11 smartest people.