Mickey Finn's scam inspired Chicago restaurant workers to rebel against stingy tippers by poisoning their food and would later be immortalized with the nefarious phrase "slip a Mickey."

Early 1900s Chicago was likely not a city in which you’d want to go out drinking That’s because pickpocket-turned-bar owner Mickey Finn was scamming gullible customers by spiking their drinks with an illegal drug he got from a witch doctor.

His association with the drug later inspired the manufacturing of another illegal substance, appropriately called “Mickey Finn,” that was used by vengeful waiters so often that it begat a food poisoning epidemic across Chicago.

Not to mention, this scheme is said to be the origin of the nefarious phrase to “slip a Mickey.”

The Seedy Origins Of Mickey Finn

Not much is known about Michael “Mickey” Finn except that he was born in Indiana in 1871 to Irish immigrant parents and grew up on the streets. He survived by making a not-so-honest living as a pickpocket and thief, typically going after drunken bar patrons who were easy to rob.

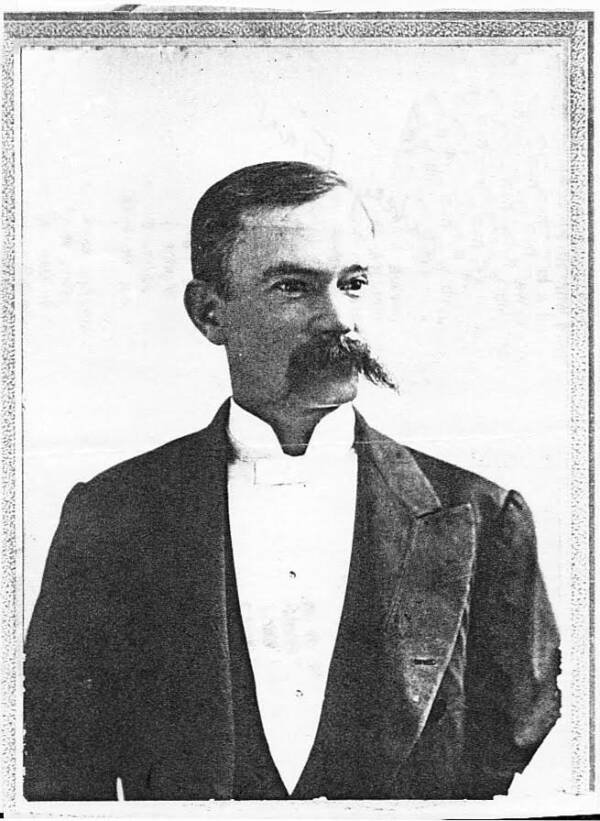

Wikimedia CommonsAmerican writer Ernest Jarrold was best known for his charming Irish character, Mickey. Rowdy and troublesome Finn was likely called “Mickey” ironically.

His nickname “Mickey” is believed to have been taken from the scampy Irish fictional character created by late 19th Century writer Ernest Jarrold. But even these points are subjects mostly of speculation, what is known about Finn, however, was that he made his way to Chicago, Illinois, and began working in the Windy City’s seedy Levee district as a barkeeper.

According to crime writer Herbert Asbury’s 1940 book Gem of the Prairie: An Informal History of the Chicago Underworld, Finn truly made his mark at the 1893 World Columbian Exposition and soon afterward took up a job at Toronto Jim’s in the city’s “Whiskey Row.” But his trouble-making ways caught up to him there when he socked a customer with a bung-starter — the mallet bartenders use to whack loose keg beers — so hard that his eye popped out.

Needless to say, Finn found himself out of a job after that stunt.

But he persevered and around 1896, opened his own saloon, the Lone Star Café and Palm Garden, in the heart of Chicago’s Levee District. He ran the business with his wife, Kate Roses.

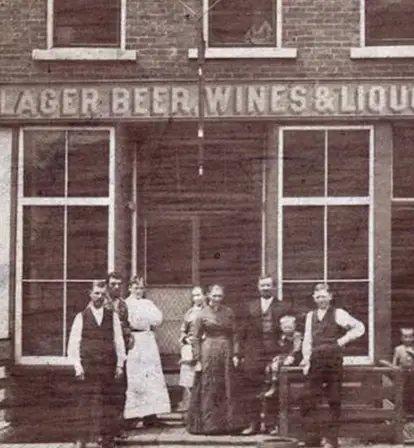

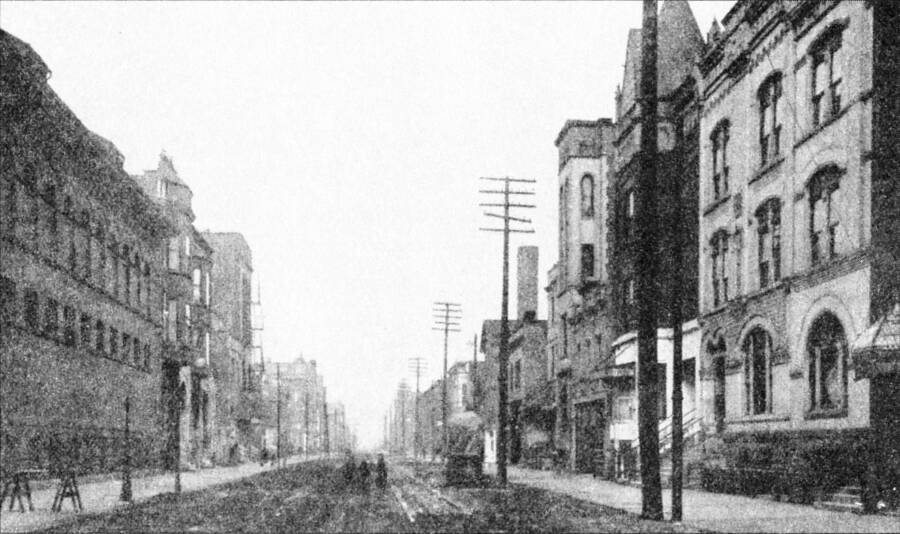

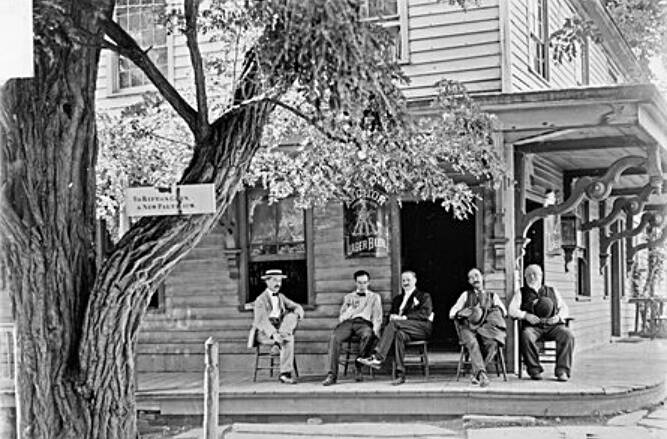

Wikimedia CommonsThe Levee Distrct was like Chicago’s own red-light district from the 1880s until 1912.

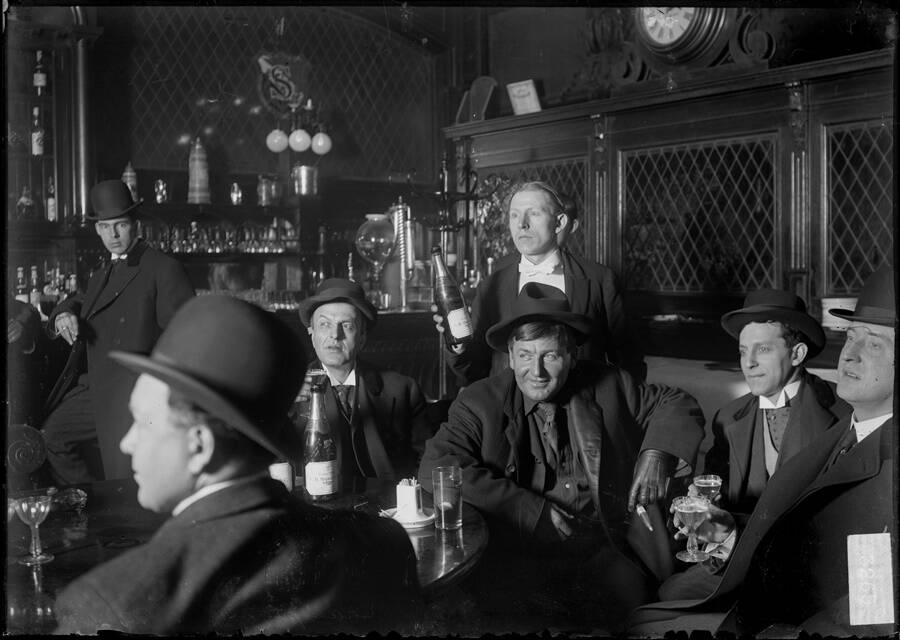

Finn’s saloon was a “black-and-tan bar,” a term used to describe establishments where black, white, and immigrant patrons mingled. But this wasn’t because of some progressive ethic, rather, these types of venues were considered lower-class than other bars in wealthier neighborhoods.

The modest venue served only beer and whiskey and was staffed by “house girls” managed by Roses. Many of the girls were street prostitutes with unsavory names like Isabel “the Dummy” Fyffe and Mary “Gold Tooth” Thornton, whose jobs were to flirt with patrons and encourage them to buy more drinks. Gold Tooth would later provide testimony that supplemented Asbury’s novel.

But running a straight business wasn’t enough for the couple; they wanted more. So Finn hatched a plan to steal from his most heavy-pocketed customers.

Slipping Them All A Mickey Finn

Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection/Chicago History Museum/Getty ImagesBack then, saloons that served a mix of clientele were deemed lower-brow establishments.

Mickey Finn’s scheme was simple. He invented an eponymous cocktail called the “Mickey Finn Special” that he promoted on the saloon’s sign. It was a pricey drink — meant to lure those with enough cash in their pockets worth robbing — with no mention of what was in it.

The special drink, in fact, was a mix of alcohol, Tabasco, snuff-soaked water, and a white liquid that could knock out an adult man in seconds.

The milk-white substance was allegedly chloral hydrate, a sedative that was first produced in the 1830s and was supplied to Finn by a drug dealer-slash-voodoo doctor who went by the moniker Dr. Hall.

After a customer passed out from the drink, Mickey Finn’s bar team would wait until the venue was empty before dragging the unconscious patron into one of the back “operating rooms.” The customer would then be stripped of their possessions and the girls and Finn’s barkeep would each get a percentage of the loot.

PixabayThe drug Finn used in his robbery scheme was believed to be chloral hydrate, a sedative cooked up in the 1830s.

After, they’d throw the victim out into the alley, penniless and none the wiser as to what happened to him.

It was an almost fail-proof crime. To divert public suspicion, Finn gave bribes to local authorities. But regardless of how careful he was, he could never prevent the loose lips of Gold Tooth and Dummy from ratting him out.

In December 1903, Gold Tooth and the Dummy confessed to Chicago police, who arrested Finn and closed up his shady business for good.

According to a Chicago Daily Tribune report of Finn’s indictment published on Dec. 16, 1903, Gold Tooth gave the court incriminating testimony of Finn’s drug-robbery operation:

“I worked for Finn a year and a half and in that time I saw a dozen men given ‘dope’ by Finn and his bartender. The work was done in two little rooms adjoining the palm garden in back of the saloon.”

Gold Tooth’s testimony was enough to arrest Mickey Finn and launch an investigation that put the saloon out of business.

Chicago History MuseumMen outside a saloon in Chicago. After reports of the dopings began to circulate, police began to suspect Mickey Finn’s scheme.

Though it would be the last Chicago would hear of Mickey Finn (he moved out of town after his business shuttered), unfortunately, it wouldn’t be the last of these kinds of crimes in the Windy City.

The Food Chicago Food Poisoning Epidemic

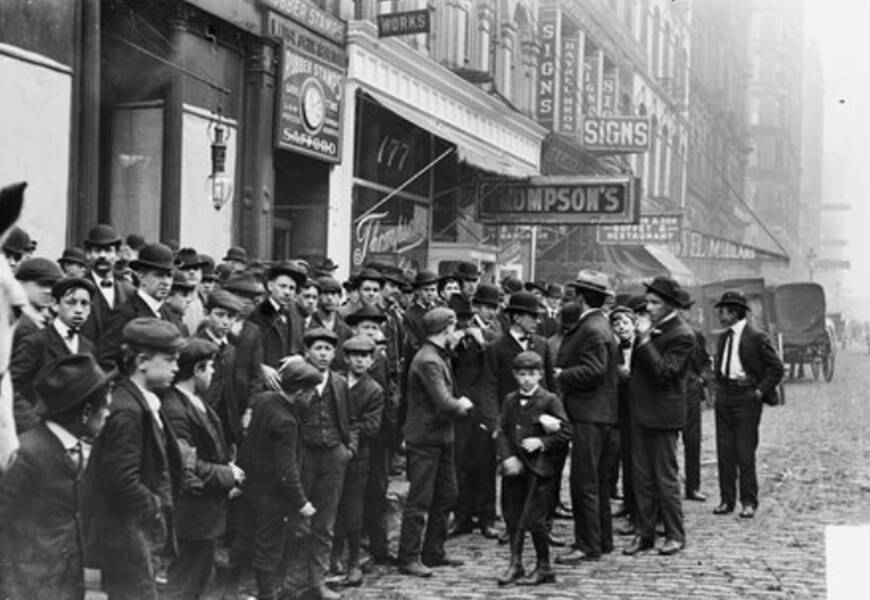

Chicago History MuseumThe waiter’s strike of 1903 occurted the same year that Mickey Finn was arrested.

In the summer of 1918, police launched a major raid at the offices of Chicago’s waiter’s union. They rounded up more than 100 servers working in the local restaurant industry on suspicion of food poisoning.

The raid was unlike anything that the city had seen before and it came after the swanky Hotel Sherman hired an undercover detective to investigate an alarming amount of food poisonings among the hotel’s well-to-do patrons.

What the detective discovered was astonishing: the city’s waiters had been purchasing 20-cent packets of an illegal powdery substance that, if ingested, would cause violent gastronomical problems. The drug was later found to be “tartar emetic,” a concoction produced by W. Stuart Wood, a pseudo pharmacist who manufactured the drug with his wife.

Wood named the drug “Mickey Finn powder” as a tribute to the conniving saloon owner who was arrested just 15 years earlier. Many believe that this was the origins of the saying “slip a Mickey” as a reference to being drugged or knocked unconscious by a spiked beverage or meal.

Chicago History MuseumThe Sherman Hotel hired a detective to investigate after an alarming number of diners became ill.

The drug bust at the waiters’ union explained the cause behind countless reports of food poisoning that had occurred across Chicago in previous weeks.

Customers at restaurants, clubs, and hotels in the city were getting sick, shaking and vomiting uncontrollably after consuming what authorities suspected was food laced with some sort of drug. Police confiscated envelopes filled with the Mickey Finn powder adorned with a written warning on them:

“One of these powders may be given in beer, tea, coffee, soup or any other liquid. Never give more than one powder a day. These powders are to be used by adults only.”

Among those arrested in the raid were two men who worked the union headquarters’ bar, along with the president of the subsidiary bartenders union, officials from the waiters and Cooks unions, and, of course, Wood, who was the mastermind behind the powder drug.

According to a report by the Tribune, the customers that had fallen ill during the food poisoning epidemic were mostly “prominent Chicagoans” who hadn’t tipped their waiters generously.

Drugs, Poison, And Revenge In Chicago’s Restaurants And Bars

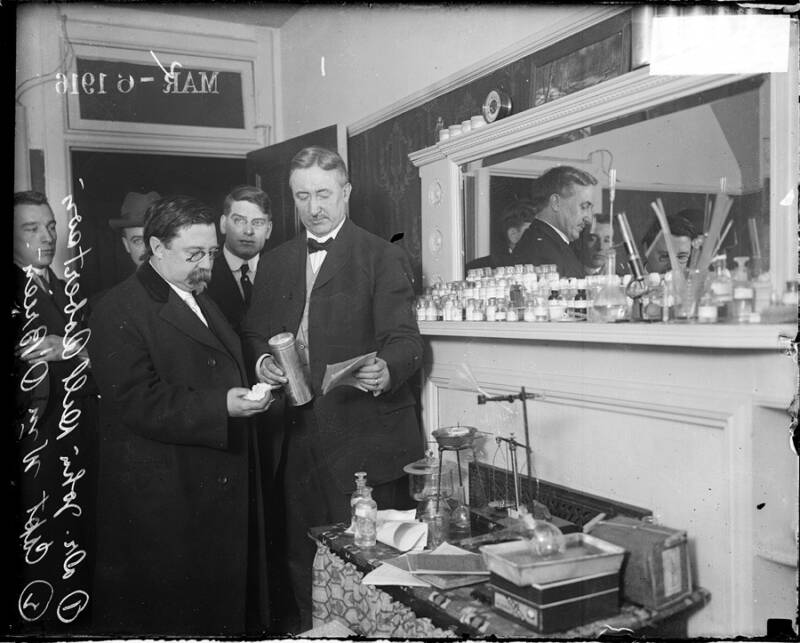

Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection/Chicago History Museum/Getty ImagesCaptain William O’Brien and Dr. John Robertson examine poison phials in the room of Jean Crones, the anarchist who poisoned 300 elite guests.

Even before Chicago waiters plotted against stingy tippers, another bout of mass food poisoning occurred during a swanky event at the University Club, where dozens of the city’s elite including the mayor and the governor had gathered and become gravely ill, two years prior in 1916.

More than 100 guests at the soiree, held in honor of Chicago’s new archbishop George Mundelein, became sick after consuming chicken soup at the event. It turned out that the food had been spiked with arsenic by Nestor Dondoglio, an Italian anarchist who advocated for class revolt and had only meant to poison Mundelein himself.

Dondoglio had disguised himself as an assistant chef named Jean Crones and slipped in among the kitchen staff unnoticed before carrying out his revenge against the city’s influential crowd.

After both these incidents of food poisoning, Chicago’s food industry descended into fear and chaos.

The city’s public was on high alert. Food tasters were hired for the city’s St. Patrick’s Day festivities as waiters across Chicago continued to strike and, in some cases, still poisoned stingy restaurant tippers.

Though separated by decades, Dondoglio’s, the waiters, and Finn’s stunt all sought to revolt against Chicago’s rich. Later, drugs and poison would escalate from a means for punishment to a method for murder.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesCartoon depicting a man suffering from food poisoning, a trend which kicked off in the fallout of Mickey Finn’s own scheme.

In 1923, Chicago storekeeper Tillie Klimek — nicknamed the “Poison Widow” — made headlines after she was convicted of killing her third husband by poisoning his meals. Later, she was linked to the murders of at least 14 other people and animals.

Similarly, in 1931, a woman in Chicago’s Rogers Park was suspected of using flypaper to poison her husband’s drinks when she believed he was having an affair. Then in 1942, a couple died of cyanide poisoning at the famed L’Aiglon in River North, and later it came out that the woman in the couple was a mistress.

While this trend of mass poisoning bloomed in 1920s and ’30s Chicago, these days pulling off such a crime would be virtually impossible.

“The truth is it’s generally not easy now to [poison] on a wide scale,” said food safety specialist Benjamin Chapman of the Department of Agricultural and Human Sciences at North Carolina State University.

He added: “Cases of intentional poisoning tend to be small — and often a flavor or a taste will tip people off something’s wrong. Using our food systems to poison is just not the most efficient, effective way to get at people.”

Mickey Finns have since transformed into knock-out drugs made out of clonidine. The drug continues to be the go-to method for scammers and thieves.

So, next time you’re out drinking, be mindful of your drink and make sure nobody slips you a Mickey.

Now that you’ve learned about Mickey Finn and the origins of the term “slip a Mickey,” discover the true tale of the Angels of Mons, the World War I myth that captivated Britain. Then, meet Emma Lazarus, the courageous Jewish poet behind the poem on the Statue of Liberty.