Mike Day was leading a raid against an al-Qaeda hideout in 2007 when he was shot more than two dozen times, and though he recovered physically, he eventually took his own life in 2023.

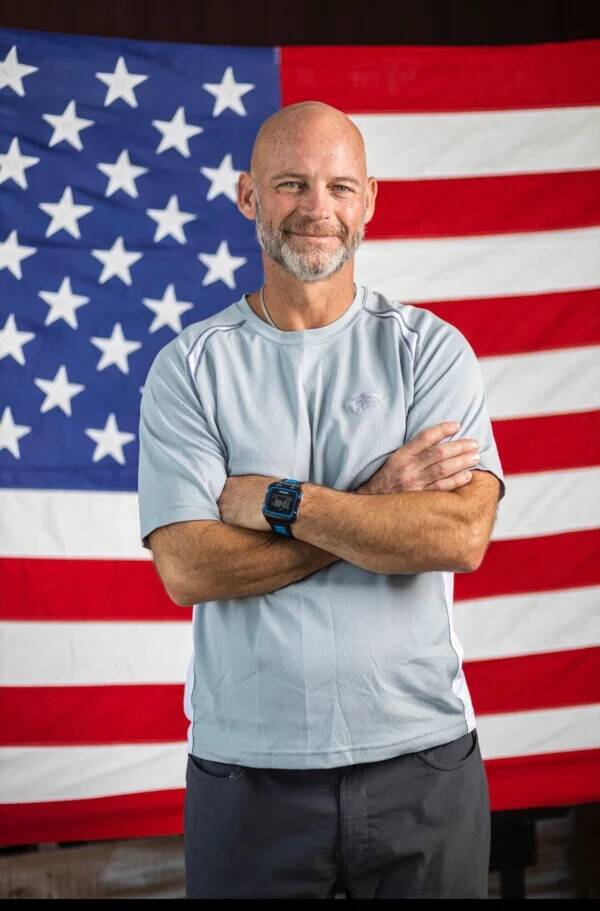

Altmeyer Funeral Homes & CrematoryDouglas “Mike” Day, a former Navy SEAL and author who worked as an advocate for veterans.

Mike Day was the first member of SEAL Team 4 through the door on April 6, 2007, when his unit raided an al-Qaeda cell in Iraq’s Anbar Province. As soon as he stepped inside, he faced a barrage of gunfire. Several shots even struck his rifle, knocking it from his hand.

Behind Day, Iraqi scouts providing backup were forced back into the hallway by the gunfire. One was killed immediately. Meanwhile, an insurgent charged Day with a grenade, but though Day quickly shot the insurgent, the grenade still went off. Day was knocked unconscious.

When his fellow Navy SEALs finally found Day, they were met with a gruesome sight. He didn’t realize it, but Day had been shot 27 times — 16 times in his body, and 11 times on body armor. The body armor should have only been able to absorb one bullet. Yet, somehow, he was alive.

Day’s physical recovery was grueling, and it took time, but he did recover. Afterward, Mike Day retired from the SEALs and began to focus on behavioral health and advocacy for fellow veterans. He even published a successful book in 2020 entitled Perfectly Wounded. By all metrics, Day had survived against impossible odds and managed to live a good life.

Sadly, though, Day had developed deeper scars than the ones the bullets had left. He came to believe that the world would be a better place without him in it, a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression that plagued him. And on March 27, 2023, Mike Day died of suicide.

This is his story.

Mike Day’s April 2007 Navy SEAL Mission

Mike Day enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1989 and, by 2007, was serving in the Iraq War as a U.S. Navy SEAL.

Wikimedia CommonsMike Day was part of Navy SEAL Team 8 in 2000.

Day was experienced. According to his memoir, Perfectly Wounded he had been on hundreds of missions with various Navy SEAL platoons. But SEAL Team 4, Foxtrot Platoon, stood out to him.

“We were at the top of the warrior food chain,” Day wrote. “Together we were lethal… We were a lethal war-fighting organism able to seek out, capture, and destroy the enemy, anywhere.”

Come April, SEAL Team 4 was preparing for the final mission of its deployment. It was a “turnover mission” to capture a high-value al-Qaeda member in Fallujah before handing over operations to the newly arrived and fresh-faced SEAL Team 10. For many of them, it would be their first ever mission — and Day knew it would be risky.

“In less than two weeks, our entire team would rotate back to the United States,” he reflected. “I knew that this mission was imminent, as our target was a hardcore [al-Qaeda] terrorist who led an effective cell of fighters. This particular terrorist group had shot down four of our medevac helicopters, killing everyone onboard; they had stripped our dead of their weapons, clothes, and gear.”

Day was selected to be the assault force commander on the mission. In all, there were 22 operators assigned to it, a mix of SEALs and Iraqi scouts. They were to infiltrate a single-story, walled compound in northeast Fallujah and find their target. For someone like Day, it was a routine assignment.

But the mission on April 6, 2007 would transform Mike Day’s life.

How Mike Day Was Shot 27 Times

United States Marine CorpsFallujah, Iraq, in 2004.

Mike Day’s team split into two groups: one to cover the outside, another to move inside and clear rooms. Day led the interior group, meaning he would be the first one into a room. Among his group of SEALs, this was a highly coveted honor: “We all want to be the first into the fight, and every SEAL is willing to accept the greater risk, especially for his buddy’s sake,” Day wrote.

But the second that Mike Day stepped through the door of a small room that day, it became clear that the mission of April 6, 2007, would be like no other.

“As I pivoted off my right foot to move down the left wall, I had the sensation that my body was being slammed with a dozen sledgehammers,” Day wrote. “…It was surreal, like something out of a movie: time slowed almost to a stop and everything happened in super slow motion, almost as if I were watching the scene unfold frame by frame.”

Four insurgents hiding in the room had opened fire on him. Their barrage of bullets caused Day to drop his rifle, while other bullets rocketed past him and into two Iraqi scouts standing in the hallway. As Day was struck by a hail of bullets, his first thoughts were of his family back home.

U.S. Air ForceAs he was being shot, Mike Day’s training as a U.S. Navy SEAL kicked in.

But his next thought was to complete the mission.

“After I realized that I actually was getting shot, my second thought was, ‘God get me home to my girls, and then extreme anger,” Day recalled in a 2014 interview. “Then I just went to work. It was muscle memory. I just did what I was trained to do.”

He grabbed his pistol and fired it at the insurgents. Day killed one of the men who had shot at him. Then he saw a second man, reaching for a grenade in his vest and pulling the pin. Day fired his pistol again and stopped the man in his tracks — but not the man’s grenade, which dropped from his hand, rolled toward Day, and detonated.

Everything went black.

When Mike Day regained consciousness a few minutes later, he sprung back into action. As the two remaining insurgents opened fire on Day’s fellow Navy SEALs, he started shooting at them. They turned and returned fire — but Day was able to kill them both.

He then tried to radio his team, but Day’s radio had been damaged during the firefight. Nearby, Day found the body of his fellow SEAL Joseph “Clark” Schwedler, and used his fallen comrade’s radio to contact the rest of his men.

Had he been delayed even a moment longer, the building would have been destroyed in a fire mission. Instead, the strike was called off, and the rest of the team moved in to find Day and the other survivors. From the look on their faces, he finally understood just how much damage he had sustained.

The Long And Difficult Road To Recovery

Mike Day/InstagramMike Day recovering in the hospital.

“I didn’t even know how bad I was hurting until they came in and I saw the looks on their faces,” Day told Coffee or Die magazine in a 2020 interview. “We all know that look.”

In addition to 16 bullet wounds directly on his body and 11 hits to his body armor, Day had also taken shrapnel from the grenade that knocked him out. Despite that, he was able to walk to the medical helicopter without any support.

“I wasn’t being macho, but I was afraid if they picked me up, it would just hurt more,” he told Coffee or Die.

Mike Day was transported to Baghdad where medics stabilized him overnight. The next day, he was flown to Germany for more treatment.

On the way, he suffered three cardiac arrests.

Wikimedia CommonsAdmiral Mike Mullen presenting Mike Day with the 2008 Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs Grateful Nation Award.

He was then transferred once again to Walter Reed National Military Center, where he remained for 16 more days while he recovered. The estimated recovery time was three to four months, but Day joked that he was “such a pain in the butt, they were ready for me to go.” Speaking more seriously, he attributed his survival to a desire to see his children again and his history of overcoming trauma.

“As a child, I didn’t know that trauma and resiliency would become my default programming, or how much it would shape my thoughts, beliefs, relationships, and behaviors,” Day said. “… My childhood was not exactly idyllic, but it’s what happened to me and I’m very grateful for all of it. The wounds of my childhood trauma served as the foundation of some truly excellent resiliency training.”

But though Mike Day’s body was healing, he still had a lot of recovery to do. And some of his wounds would prove to be more difficult to overcome than others.

Mike Day’s Retirement From The Military And Tragic Suicide

Mike Day retired from the Navy in 2010, after 21 years of service. He spent the next seven years as a wounded warrior advocate for the U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) as a non-medical case manager, though Day would instead refer to himself as a “case fixer.” Unable to leave behind his SEAL determination, Day went above and beyond for his clients. Sometimes, that meant taking a less-than-courteous tone with hospital staff or managers who he felt provided “insufficient care.”

“It was all worth it for the people whom I was privileged to represent,” he said. “Their wounds were so much worse than mine. They are the greatest examples of human resiliency that I have ever encountered. They motivated and humbled me; I was honored to be their care manager.”

Throughout his time as an advocate, however, Day was also grappling with his own mental health. He said his childhood trauma had made him resilient, but he also acknowledged that “compartmentalizing” was one of the ways he had coped. All too often, those compartments don’t remain shut forever. Coupled with the trauma he experienced in combat, the effect it started to take on his mental health was proving detrimental.

Mike Day/InstagramMike Day with his dog, Herja.

Day referred to the period between his advocacy efforts and the publication of his book as a “downward spiral” that culminated in hopelessness. Stress, trauma, and what he called “psychological deficits” turned into suicidal ideation and a desire to justify ending his life to his family — the same family that drove him to survive his experience in Iraq in the first place.

“I still felt trapped in a life layered with overwhelming stress, endless responsibilities, meaningless tasks, and toxic people, of whom I felt I was the most toxic,” Day explained in his memoirs. “It was all my fault. I felt I was my own worst enemy. This time there was a bullet in the chamber. I was beyond contemplation; my mind was made up.”

Mike Day was moments away from ending his life when he got a phone call from his boss, Scott Heintz, telling him to take time off work. Heintz told Day he would still pay him for the next three months, so long as Day took the time to “chill out” and recover from his burnout. It was a kind gesture, one that came at the perfect moment.

Mike Day started trying to focus on his own mental health. He met with physicians who focused on depression and its various causes — not just latent mental trauma, but physical causes like biochemistry, genetics, gut health, and environmental factors. Day was prescribed a regiment of probiotics, hormone therapy, and exercise to manage his depression.

After about two months, Day said it “felt like the black cloud that had been hovering over me for years was gone.” And when he published his book in 2020, Day concluded with an optimistic outlook and the feeling that, finally, he was in control of his life and mind. His story seemed to have a happy ending.

But on March 27, 2023, Mike Day died by suicide.

Mike Day/InstagramMike Day was just 47 years old at the time of his death.

The news was shocking. Devastating. Mike Day had survived so much, and yet his scars from war had proven to be too much for him to bear. Sadly, Day is one of many war veterans who die from suicide.

In December 2024, the Department of Veterans Affairs released the most recent National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. The report analyzed data from 2001 to 2022 — the most recent year for which data was available — showed that the rate of veteran suicides in the United States has only continued to increase.

In 2022 alone, there were 6,407 suicides among veterans — around 18 per day. On average, seven suicides per day were among veterans who received Veterans Health Administration care in 2021 or 2022.

There is no easy to solution to the suicide crisis among veterans. When it comes to Mike Day, the very least we can do is remember his bravery, both while fighting enemy combatants during his time as a Navy SEAL, and while battling his own personal demons after it.

After reading about Mike Day’s tragic story, read about the complicated legacy of Richard Marcinko, the founder of U.S. Navy SEAL Team Six. Then, read the sad story of Christine Chubbuck, the reporter who shot herself live on air.