Found at the Nescot archaeological site in 2015, these largely corgi-like canines were believed to have been ritually killed in various ceremonies, likely in honor of deities such as Pluto, god of the underworld, and Hecate, goddess of witchcraft and the Moon.

Ellen GreeneA dog skull unearthed among the thousands of Roman-era canine bones discovered at the Nescot archaeological site in England.

Archaeological excavations at the former Animal Husbandry Center of Nescot College that were conducted in 2015 revealed a startling mystery: a Roman-era quarry pit filled with a staggering number of dog remains. In total, researchers found 5,436 bones belonging to at least 140 individual dogs — one of the largest assemblages of canine remains ever found in Roman Britain.

But for the better part of the past decade, no one knew exactly why these dogs had been buried here en masse. A recent study by Dr. Ellen Greene published in the International Journey of Paleopathology, however, may finally shed light on some of these mysteries while also raising further questions about the role of dogs in Roman and Romano-British religious practices.

Thousands Of Dog Bones From Roman-Era Sacrifices Found In England’s Nescot Quarry

Ellen GreeneThe dog bones found in the Nescot quarry largely came from corgi-like canines of small stature with short legs.

In 2015, archaeological excavations at England’s Nescot College in Ewell, Surrey revealed a roughly 13-foot oval shaft dating back to the late first or early second century C.E. Experts determined that the shaft had originated as a Roman quarry pit, but it was later repurposed into a deposit for various items including human remains, coins, gaming tokens, and pottery.

Furthermore, researchers identified three distinct phases of the shaft’s use. Phases one and two included a significant amount of animal remains, while the third phase saw a sharp decline in ritual deposits and seemingly saw a transition to more mundane use of the pit. However, the sheer number of dog bones that had been deposited during the first two phases left archaeologists shocked.

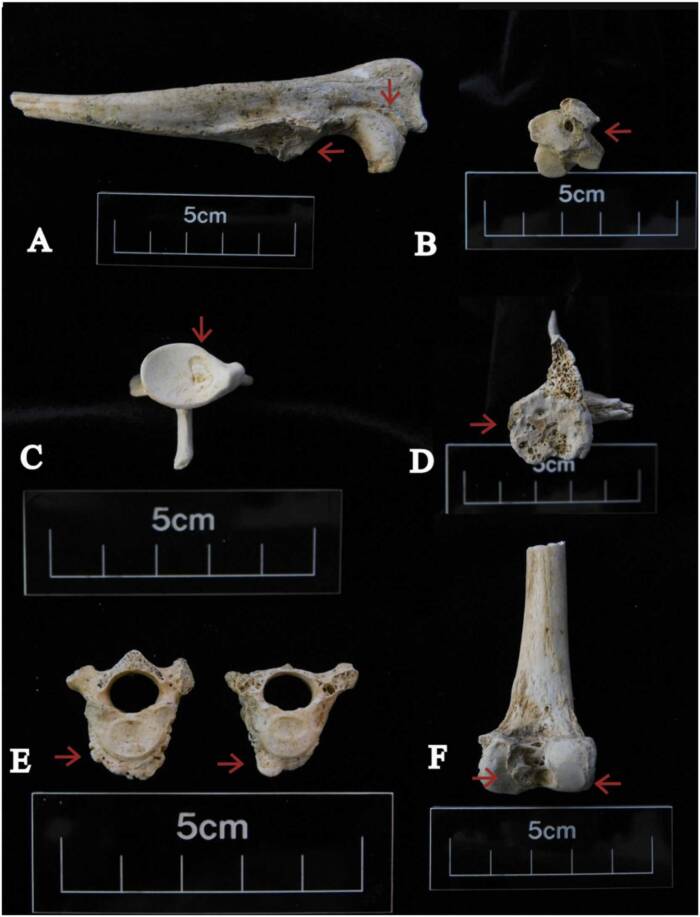

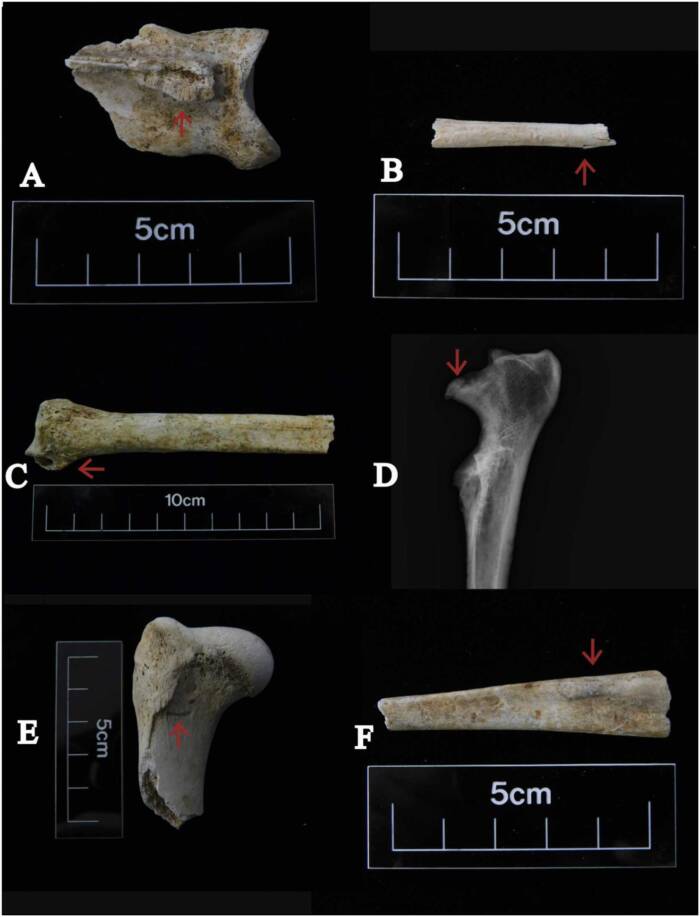

Of the 10,747 animal bones found in the Nescot shaft, more than half belonged to dogs. In total, there were 5,436 canine bones. One canine phallic bone that had been painted proved especially striking and unusual.

While dog sacrifices were not uncommon in the Roman era, the sheer amount found here was unprecedented — and as such, it presented a unique case study for researchers.

Dr. Ellen Greene certainly thought so, and now the results of her study have been published.

Analyzing The Remains Left Behind After The Ancient Nescot Dog Burials

While the dog breeds of today did not exist in the Roman era, previous research has shown that Romans had “toy dogs” and other specifically-curated breeds that resemble modern ones. Based on Greene’s analysis, the dogs buried at Nescot were mostly small breeds, though they were fairly diverse.

Some, the study notes, displayed chondrodysplasia, a genetic condition that results in disproportionately small limbs relative to body size, which would have resulted in dogs that somewhat resembled modern corgis. Other bones were similar to the modern Maltese, which aligns with historical records that indicate ancient Romans kept Maltese-like dogs.

The results also showed that many of the dogs had age-related conditions, meaning they had lived well into their later years. Additionally, the remains were largely free of any marks of trauma or butchery, suggesting they were not killed for food or fur. In all likelihood, these dogs had not been put through strenuous labor or subjected to mistreatment, but rather cared for with some degree of love and respect.

Ellen GreeneFindings were characteristic of other ritual dog sacrifices, though it’s unclear why there were so many at Nescot.

But the Nescot shaft was not simply a pet cemetery, at least according to Greene’s findings. The presence of human remains alongside the dogs implies that the shaft had, at one point, served a ceremonial or sacrificial purpose. This would make sense, given that ritually-sacrificed dogs in ancient Roman societies often displayed signs of having been well-cared-for.

“The Romans had specific rules about what types, colors, ages, and sexes of animals were appropriate for sacrifice to different gods,” Greene said. “It’s likely that these dogs were chosen based on such cultural criteria.”

This revelation does raise further questions, however. Dogs were associated with various deities in Roman mythology, and they played a central role in the daily lives of people in Roman Britain, particularly as hunters, herders, guardians, and companions. It remains unclear which deity these dogs were being sacrificed to, why small dogs were chosen for this sacrifice in particular, and whether the presence of human remains at the site could be an indicator of a more complex ritual.

Pre-Construct ArchaeologyThe ancient quarry shaft where the bones were discovered.

It is also unclear why the site lost its religious significance over time. What started as a site for ritual sacrifice eventually became a deposit for more mundane, discarded objects, and by the early second century C.E., all deposits ceased entirely.

“Despite the fact that dogs are found on the majority of Romano-British sites, very little can be said about the Nescot assemblage in terms of how it fits into the larger picture of the province because of the absence of adequate comparative data,” Greene concludes. “This problem is not limited to the dogs of Roman Britain however, and the standardization of pathological recording and reporting in zooarchaeology can only serve to strengthen the field as a whole.”

After reading about this study of ancient Roman dog sacrifices, read about some of history’s most famous dogs. Then, read about the collapse of the Roman Empire.