Researchers say North American raccoons who live in cities are beginning to look and act differently from their rural counterparts.

Joshua Cotten/UnsplashRaccoons in cities now have snouts that are 3.5 percent shorter than their rural cousins, a sign of domestication.

City folks across North America may have noticed that their resident raccoons are looking cuter than usual — and they wouldn’t be wrong.

The same process that saw wolves evolve into domesticated dogs appears to be playing out with America’s favorite “trash pandas,” according to new research from the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. One of the most noticeable signs of domestication is a shorter snout, a feature that was widely observed by researchers when they looked at nearly 20,000 images of raccoons from across the continental United States.

The new study was published in the online journal Frontiers in Zoology.

Human Trash Is A Key Factor In North American Raccoon Domestication

Domestication is sometimes thought to be an “unnatural” process initiated by humans, but that’s not necessarily the case. As researchers outlined in the study, domestication actually begins when animals become adapted to a new “environmental niche in the human environment” — essentially, when they begin to comfortably live among humans.

And one of the most impactful elements in that process is human trash.

“Trash is really the kickstarter,” said the study’s co-author Raffaela Lesch, an assistant professor of biology at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. “Wherever humans go, there is trash. Animals love our trash. It’s an easy source of food. All they have to do is endure our presence, not be aggressive, and then they can feast on anything we throw away.”

Rhododendrites/Wikimedia Commons“Trash pandas” are still wild animals for now, but they could potentially become pets someday.

Animals who follow this behavior have been rewarded in the past. Recent research suggests that dogs may have self-domesticated in much the same way, recognizing the benefits of working alongside humans to hunt and scavenge for food. Then, over thousands of years, humans selectively bred dogs with certain traits, leading to modern breeds like French bulldogs — which famously (and controversially) have extremely short noses.

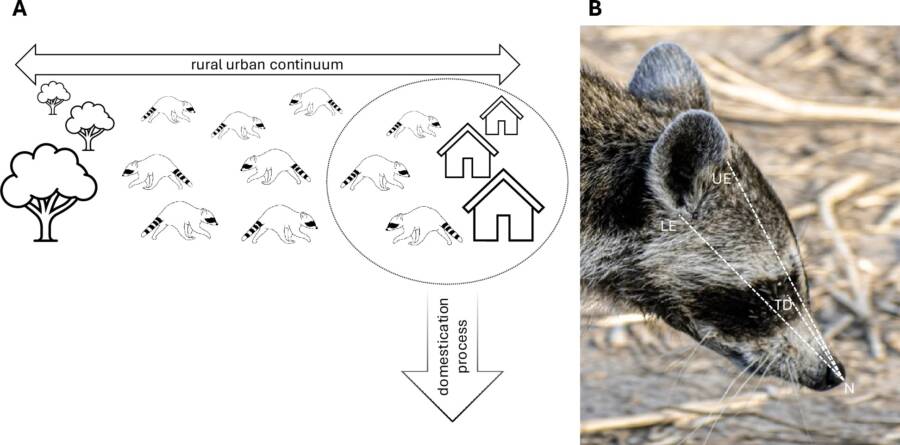

Short snouts are not the only signs of what scientists have dubbed “domestication syndrome,” though. As Scientific American noted, smaller heads, floppier ears, softer features, and white patches on fur are also signs of domestication that city raccoons are showing.

How This Study Relates To The Neural Crest Domestication Syndrome Hypothesis

According to the Neural Crest Domestication Syndrome (NCDS) hypothesis, an animal’s adrenal glands, which are formed by neural crest cells, can help predict how tame (or not tame) the animal will be. Since neural crest cells also help form the structure of the animal’s face, they’d hypothetically lead to a calmer animal and a “cuter” face with floppier ears and a shorter snout.

Though it’s a compelling theory, it’s still being actively researched.

Part of that research includes the new study published by Lesch and her 16 student co-authors. By observing, in real-time, whether raccoons were exhibiting signs of domestication, they could actively put that theory to the test. And it started in their classroom at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Lesch et al./Frontiers in ZoologyAn illustration showing the concept of comparing urban and rural raccoon populations.

“The idea behind biometry, where students learn how to code and use statistics, is a class that is difficult to teach,” Lesch said. “I wanted to teach this class in a way that students would have their own data that they collect and analyze. The benefit is that I didn’t have to push students to complete the work. They were intrinsically motivated because they cared.”

For the study, Lesch and her students analyzed nearly 20,000 photographs of raccoons from across the continental United States, thanks to the citizen science project iNaturalist.org. From their observations, they noticed that raccoons living in dense urban centers had snouts that were around 3.5 percent shorter than raccoons in more rural areas — similar to dogs.

These findings support the Neural Crest Domestication Syndrome (NCDS) hypothesis, but they don’t prove the theory entirely.

It’s just one step in the research process, but Lesch and her students want to take the work further. One student, Alanis Bradley, plans to base her Ph.D. research on validating the findings by 3D scanning various raccoon skulls, some dating as far back as the 1970s. Lesch and her colleagues also discussed expanding the research to other species like opossums.

“I’d love to take those next steps and see if our trash pandas in our backyard are really friendlier than those out in the countryside,” she said.

And who knows? If city raccoons domesticate themselves enough in the future, then perhaps one day having a pet raccoon could become a reality.

“It would be fitting and funny if our next domesticated species was raccoons,” Lesch said. “I feel like it would be funny if we called the domesticated version of the raccoon the trash panda.”

After reading about how raccoons are showing early signs of domestication, check out six odd animals that you actually can own as a pet. Or, read about the “plague” of beer-drinking raccoons that caused chaos across Germany.