While smallpox blankets may be a popularly accepted truth in American history, there is just one recorded case of colonists giving disease-infected blankets to Indigenous Americans.

The arrival of white settlers in North America devastated Indigenous populations. Over the centuries, the colonists warred with Indigenous Americans, gobbled up their land, and forced them onto reservations. But did they also deliberately infect Indigenous Americans with smallpox blankets?

Though the story of the blankets infected with smallpox looms large in American history, with one doctor calling it “bioterrorism,” the truth is complicated. There is just one recorded case of colonists using smallpox blankets to deliberately spread disease among Indigenous Americans in 1763.

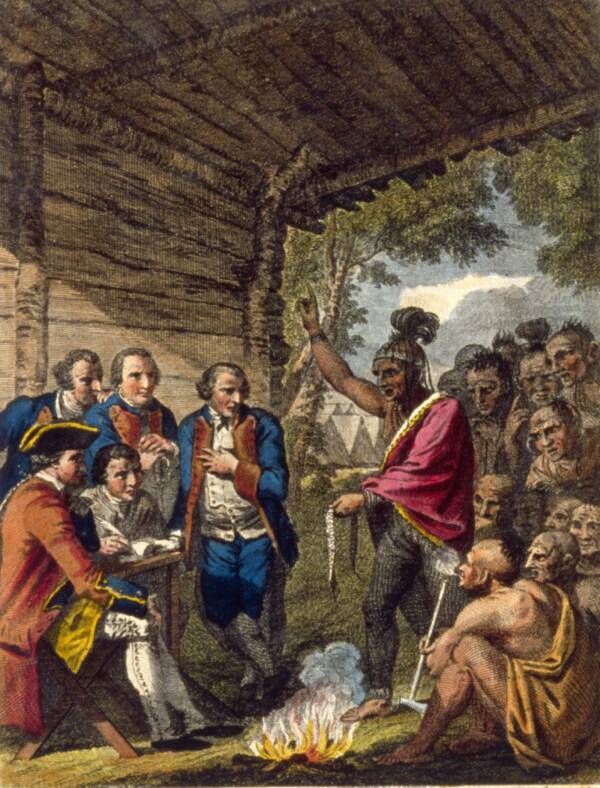

MPI/Getty ImagesA depiction of a confrontation between Pontiac, an Ottawa chief, and Colonel Henry Bouquet, a British soldier who suggested using blankets to spread smallpox to Indigenous Americans.

That said, it’s indisputable that smallpox ravaged America’s indigenous people in the 18th century — and beyond.

Not only did Indigenous Americans suffer from subsequent waves of the disease, but the scourge of smallpox also molded how Indigenous Americans view the federal government today.

This is the true story about the alleged use of smallpox blankets — and the dark history surrounding it.

How Colonists Used Smallpox Blankets Against Native Americans In 1763

The only recorded incident of smallpox blankets used as weapons happened in Pennsylvania in the late spring and early summer of 1763. Then, Delaware, Shawnee, and Mingo warriors, led by Ottowa Chief Pontiac, besieged Fort Pitt in present-day Pittsburgh.

Though the warriors perhaps didn’t know it, smallpox had broken out within the fort’s walls. And on June 24, 1763, the fort’s commanders decided to try and use the disease to their advantage.

The fort’s 22-year-old commander, Captain Simeon Ecuyer, gave Indigenous Americans warriors several items infected with smallpox following unsuccessful peace talks.

Public DomainSir Jeffrey Amherst’s legacy is tied to smallpox blankets, although his role in their use is convoluted.

“We gave them two blankets and a handkerchief out of the smallpox hospital,” Captain William Trent, a militia captain, wrote in his journal. “I hope it will have the desired effect.”

Though Ecuyer and Trent seemed to have acted independently, their superiors had the same idea. Ecuyer’s superior, Colonel Henry Bouquet, told his superior, Sir Jeffery Amherst, about Fort Pitt’s smallpox outbreak on June 23. And Amherst mused in his July 7 response about harnessing the disease to fight back against the Indigenous Americans.

“Could it not be contrived to Send the Small Pox among those Disaffected Tribes of Indians?” Amherst wrote to Bouquet. “We must, on this occasion, Use Every Stratagem in our power to Reduce them.”

Bouquet agreed. On July 13, he replied, “I will try to inoculate the bastards with some blankets that may fall into their hands, and take care not to get the disease myself.”

Amherst responded a few days later, saying that Bouquet should try using the infected blankets “as well as try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execreble [sic] Race.”

Wikimedia CommonsIn 1763, British soldiers Jeffrey Amherst, Thomas Gage, and William Trent conspired to use smallpox blankets against Delaware and Shawnee tribesmen at Fort Pitt (pictured here).

However, it’s unclear if Bouquet instructed Ecuyer to use smallpox blankets a second time or if the original blankets impacted the Delaware warriors.

Sme 60 to 80 Indigenous Americans got sick and died around this time, but it’s possible they were infected by smallpox already circulating in the region. They could have also caught the disease after taking items from settlers who they killed and abducted.

But less than 100 years later, a more devastating wave of smallpox decimated Indigenous American tribes, killing as many as 150,000 in the Midwest. Did smallpox blankets have something to do with it?

Did Americans Use Smallpox As A Biological Weapon?

At the end of the 20th century, a historian named Ward L. Churchill claimed that the smallpox epidemic of 1837-1838, which wiped out tens of thousands of Indigenous Americans in North Dakota, had been started by the U.S. Army.

“The blankets had been gathered from a military infirmary in St. Louis, where troops infected with the disease were quarantined,” Churchill wrote in his 1997 book A Little Matter of Genocide.

Captain Samual Eastman/National Library of MedicineAn 1857 depiction of a Indigenous American medicine man caring for a member of his tribe.

“Although the medical practice of the day required the precise opposite procedure, Army doctors ordered the Mandans [tribe] to disperse once they exhibited signs of the infection. The result was a pandemic among the Plains Indian nations which claimed at least 125,000 lives.”

In other words, Churchill asserted that the U.S. government had used smallpox blankets intentionally to perpetrate a genocide of Indigenous Americans. But is it true?

Simply put, no. Churchill’s claim about the U.S. Army was later found to be fabricated, according to Salon. But smallpox did devastate Indigenous Americans in the 1830s.

The epidemic started when a steamboat called St. Peter’s stopped at Fort Clark, North Dakota, along the Missouri River. The boat had infected passengers, and the disease soon spread throughout the nearby tribes.

But contrary to Churchill’s claim, U.S. government officials actually sought to stem the epidemic. Thomas Brown, an assistant professor of sociology at Lamar University who helped discredit Churchill’s research, explained in a 2006 paper published by the University of Michigan that an Indian Bureau subagent named Joshua Pilcher, who was on the boat, suggested an aggressive vaccination program to combat the disease.

Though he worried that Indigenous Americans would distrust vaccines and blame them for otherwise unrelated deaths, Pilcher wrote to his superior, “If furnishd with the means, I will cheerfully risk an experiment which may preserve the lives of fifteen or twenty thousand Indians.”

Pilcher’s colleague, William Fulkerson, similarly warned that “the small pox has broke out in this country and is sweeping all before it — unless it be checked in its mad career I would not be surprised if it wiped the Mandan and Rickaree [Arikara] Tribes of Indians clean from the face of the earth.”

Regardless of how the epidemic had started, it devastated Indigenous Americans. Suspicious that European settlers had spread the disease intentionally but unable to stop its scourge, they often turned to desperate means to prevent its spread. History Net reports that people flung themselves off cliffs, killed themselves or their families, and impaled themselves with arrows.

In the end, the epidemic killed tens of thousands. But it also did more than that. Rumors of smallpox blankets also planted a seed of distrust among Indigenous Americans toward the federal government that remains to this day.

How The Smallpox Blankets Myth Endures To This Day

Stories about smallpox blankets — both true and false — are important in our own time. As The Washington Post pointed out, COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Indigenous Americans can be traced to events like smallpox.

Government Accountability OfficeToday, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Indian Health Service is responsible for providing public medical, dental, and preventative care to federally-recognized tribes.

The use of smallpox blankets, an Oglala Lakota doctor told the paper, was “the first documented case of bioterrorism with the purpose of killing American Indians.”

Similarly, many Indigenous Americans felt far from reassured when Anthony Fauci, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director, promised Americans that the “calvary” was coming to save them from the coronavirus upon the development of vaccines.

In the end, although it’s undeniable that smallpox devastated Indigenous Americans, white settlers often turned to much more vicious methods to clear indigenous people out of their lands. They burned their homes, massacred their people, and didn’t follow their own treaties.

In that way, the story of smallpox — and smallpox blankets — is just a small part of the larger legacy of white settlement in North America. Though infected blankets were possibly used just once, white colonists relied on other violent ways to conquer the continent.

After reading about the fact and fiction surrounding smallpox blankets, delve into the tragic story of the Trail of Tears. Or, look through these stunning photos of Indigenous Americans taken by Edward Curtis.