After studying animal bones found at sites in Israel, Spain, and Africa that hold some of the earliest evidence of fire, scientists from Tel Aviv University concluded that our ancestors first used fire to preserve meat and ward off scavengers.

Tel Aviv UniversityResearcher Ran Barkai holds remains from a prehistoric elephant found at the La Polledrara site in Italy.

Fire is one of the oldest tools in humanity’s toolbox. It’s obviously both a fundamental source of heat and a time-tested way to cook food. But how and why exactly humans came to control fire is still a somewhat unclear picture.

New research from Tel Aviv University, however, proposes that humans didn’t learn how to control fire in order to cook food, but for another reason instead.

The study, published in Frontiers, suggests that fire was used by early humans to preserve meat from large animals such as elephants, hippopotamuses, and rhinoceroses for long periods of time.

Why Some Experts Think Prehistoric Humans First Controlled Fire To Preserve Meat

According to archeologists and study authors Miki Ben-Dor and Ran Barkai, humans would use the smoke from the fire to dry out the meat, therefore extending its shelf life. Fire may have also served as a way to protect the food from scavengers or other potential predators.

“The process of gathering fuel, igniting a fire, and maintaining it over time required significant effort, and they needed a compelling, energy-efficient motive to do so,” Ben-Dor said. “We have proposed a new hypothesis regarding that motive.”

Tel Aviv UniversityDeer bones that help support the researchers’ theory that prehistoric humans learned to control fire in order to smoke and preserve meat.

Ben-Dor and Barkai examined nine different prehistoric sites, including six in Africa, two in Israel, and one in Spain. All of these sites showed early uses of fire dating from 1.8 million to 800,000 years ago.

While these sites included remains of big game animals such as hippopotamuses and rhinoceroses, there was no evidence of roasted bones from meat being cooked via a fire.

“For early humans, fire use was not a given, and at most archaeological sites dated earlier than 400,000 years ago, there is no evidence of the use of fire,” Ben-Dor said. “Nevertheless, at a number of early sites there are clear signs that fire was used, but without burnt bones or evidence of meat roasting.”

This, again, suggests that fire was used not to cook or roast meat for immediate consumption, but instead to smoke the meat for future preservation.

According to Barkai, while fire was likely used initially only as a method of preservation, it was indeed eventually used for cooking as humans discovered they could use fire “at zero marginal energetic cost.”

This work is all part of a larger theory that Ben-Dor and Barkai are developing regarding early humans’ transition from hunting large game animals to smaller sources of food.

How Mastery Of Fire Fits Into The Bigger Picture Of Early Human Development

According to Ben-Dor, being able to preserve the meat of big game animals would’ve been crucial for early humans’ survival.

“From previous studies, we know that these animals were extremely important to early human diets and provided most of the necessary calories,” Ben-Dor said. “The meat and fat of a single elephant, for example, contain millions of calories, enough to feed a group of 20–30 people for a month or more.”

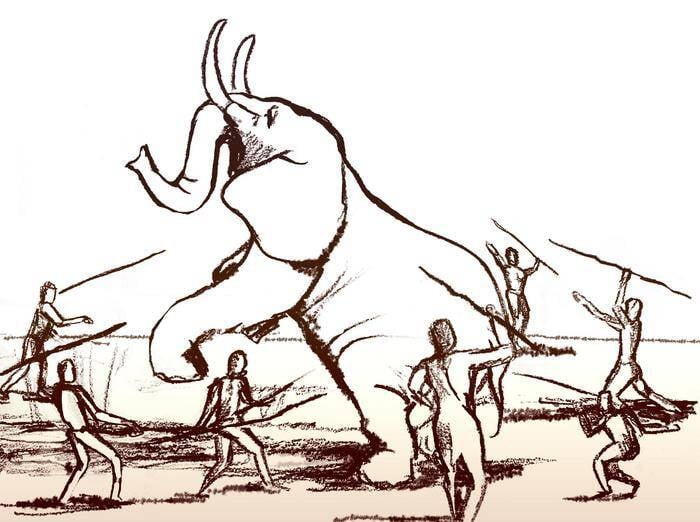

Dana Ackerfeld/Tel Aviv UniversityIllustration of prehistoric humans hunting an elephant with spears.

Essentially, it was advantageous for humans to rely on larger amounts of preserved meat as opposed to going out more frequently to hunt smaller animals.

When the populations of large animals began to decrease, the need to switch from large game hunting to small game hunting was likely a turning point for the use and development of fire as a tool.

The theory proposed in the study brings a new perspective to the prehistoric use of fire and how it fits into the larger picture of humans adjusting their eating patterns to account for the dwindling availability of large animals.

“The approach we propose fits well into a global theory we have been developing in recent years, which explains major prehistoric phenomena as adaptations to the hunting and consumption of large animals, followed by their gradual disappearance and the resulting need to derive adequate energy from the exploitation of smaller animals,” Barkai said.

After reading about this newly proposed theory on why humans started using fire, discover the story of how Neolithic parents fed their babies with animal-shaped bottles. Then, learn about the archaeologists in Norway that uncovered a 1,100-year-old boat grave of a Viking woman and her dog.