Convicted murderer William Kemmler became the first person to be executed in the newly invented electric chair on August 6, 1890, at New York's Auburn State Prison — but it went terribly wrong.

FL Historical 36/Alamy Stock PhotoWilliam Kemmler, the first man to die by the electric chair.

On August 6, 1890, a crowd gathered at the state prison in Auburn, New York. It was a beautiful, bright summer day, but they had convened for a grisly occasion: to watch William Kemmler, a 30-year-old convicted murderer, become the first man to die by electric chair.

The electric chair was supposed to be a humane way to perform executions — more humane than hanging or a firing squad. But when the electric switch was flicked at 6:43 a.m., Kemmler started to strain against his binds. After 17 seconds, the crowd realized with horror that he still wasn’t dead. The current was stopped, then started again. Four minutes later, the crowd cried out as smoke began to rise from Kemmler’s body.

This time, William Kemmler was dead. But those who witnessed his execution were horrified at how he’d died. It hadn’t been humane; it had been horrific.

“I have seen many men hanged,” a doctor at the scene remarked, “and I must say there is nothing in the old method so revolting as the scene I have witnessed this morning. The execution was decidedly not reassuring as to the scientific value of electricity as a means of execution.”

The Life And Crimes Of William Kemmler

William Kemmler is known more for his death than for his life. A native of Philadelphia, he was born on May 9, 1860. Briefly married, he eventually left his first wife for a woman named Matilda “Tillie” Ziegler. The couple settled in Buffalo, New York, where Kemmler worked as a produce peddler.

On March 29, 1889, Kemmler and Ziegler started to argue. The argument escalated, and Kemmler, who’d just returned from a night of drinking, grabbed a hatchet. He struck Ziegler more than 25 times on the head, neck, and shoulders, then confessed to their neighbor that he’d killed her.

There was no doubt of Kemmler’s guilt. But when it came time to convict him, the judge decided to use a new execution method: the electric chair. The electric chair had been invented by Dr. Albert Southwick, a dentist who had come up with the idea after watching a drunkard die of electrocution from touching an electrical generator in Buffalo.

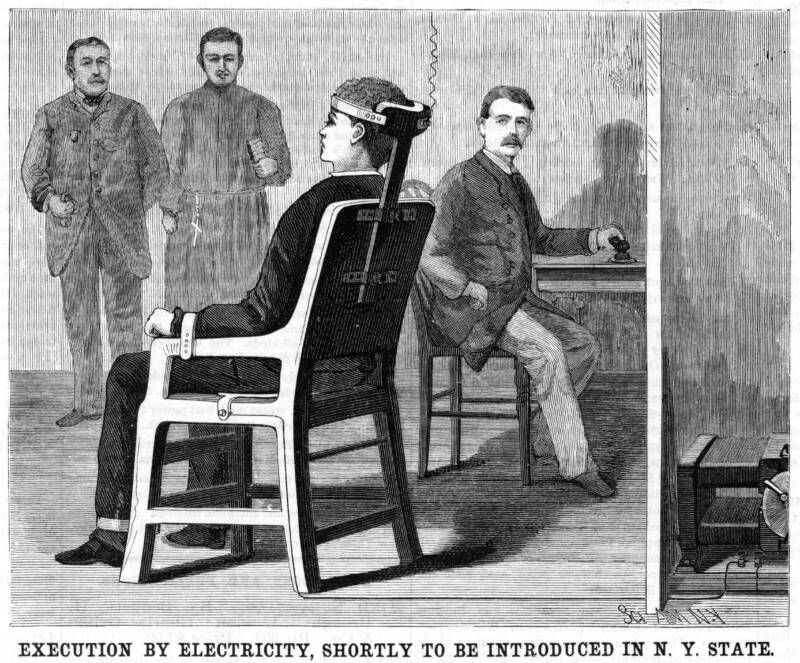

The Print Collector/Alamy Stock PhotoAn artist’s depiction of how the electric chair would look. 1890.

The man had seemingly died “painlessly,” and the electric chair thus seemed like a new, more humane method of execution.

“The sentence of the court,” the judge told Kemmler, according to court documents, “is that the defendant suffer the punishment of death, to be inflicted by the application of electricity, as provided by the Code of Criminal Procedure of the state of New York.”

“The Wretch Was Actually Tortured To Death”

The execution of William Kemmler took place on August 6, 1890. By all accounts, Kemmler was extremely calm, and so was the crowd that had come to witness his death. There seemed to be little doubt about the effectiveness of the electric chair — Thomas Edison, a pioneer in the development of electricity, had confidently stated that an electric current of 1,000 volts would kill someone instantly and painlessly.

“Gentlemen, I wish everyone all the good luck in the world,” Kemmler said once he entered the room. “I believe I am going to a good place. The papers have been saying a lot of stuff that ain’t so. That’s all I have to say.”

He remained calm as technicians guided him into the chair, and he even gently reminded the deputy sheriff that he’d forgotten to strap one of his arms into place. Then, Kemmler spoke his final words: “Well,” he told the crowd, “I want to do the best I can, and I can’t do any better than that.”

At 6:43 a.m., the executioner turned on the electric chair.

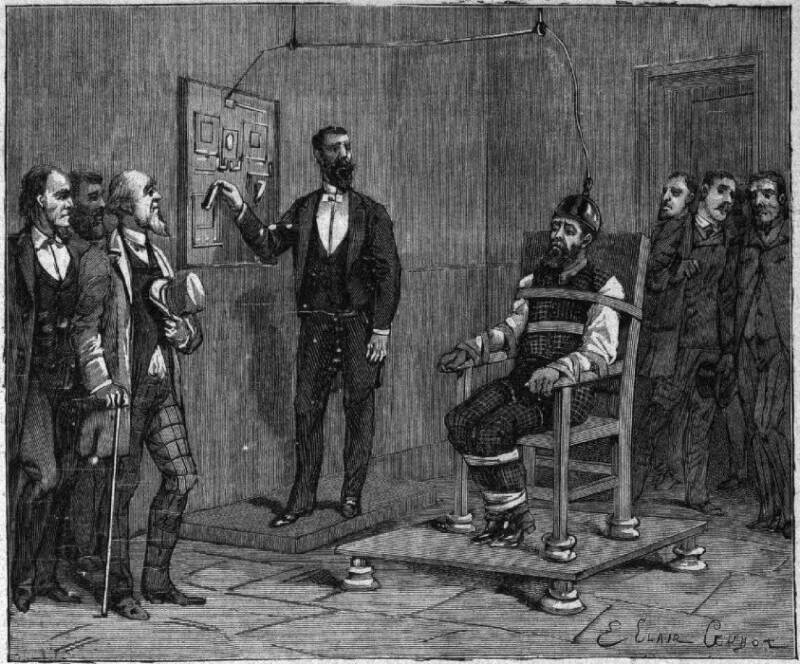

Public DomainA depiction of the execution of William Kemmler.

The crowd could see immediately that Kemmler was in agony. His face turned dark red, and his fingernails cut into his palms. He strained against his leather straps, and, as the deputy coroner of New York recalled, as reported by The Washington Post in 1990, “his shoulders slowly drew up as they sometimes do in the case of a man who is hanging.”

The executioner turned off the current 17 seconds later, and Southwick, who’d come to watch his invention in action, examined the body. Turning to the crowd, he triumphantly announced: “There! There is the culmination of 10 years’ work and study. We live in a higher civilization from this day.”

But William Kemmler wasn’t dead. The condemned man gasped and heaved; the crowd cried out, and one reporter fell into a dead faint. After a long pause, the current was restarted and left on for four minutes.

Then, at 6:51 a.m., the room began to fill with the smell of charred flesh, and the horrified witnesses noticed smoke rising from Kemmler’s back. Several people fainted or fell to the ground. The district attorney from Erie County, who had prosecuted the case, ran out of the room and collapsed in the hall.

William Kemmler was dead, but his death had been horrific.

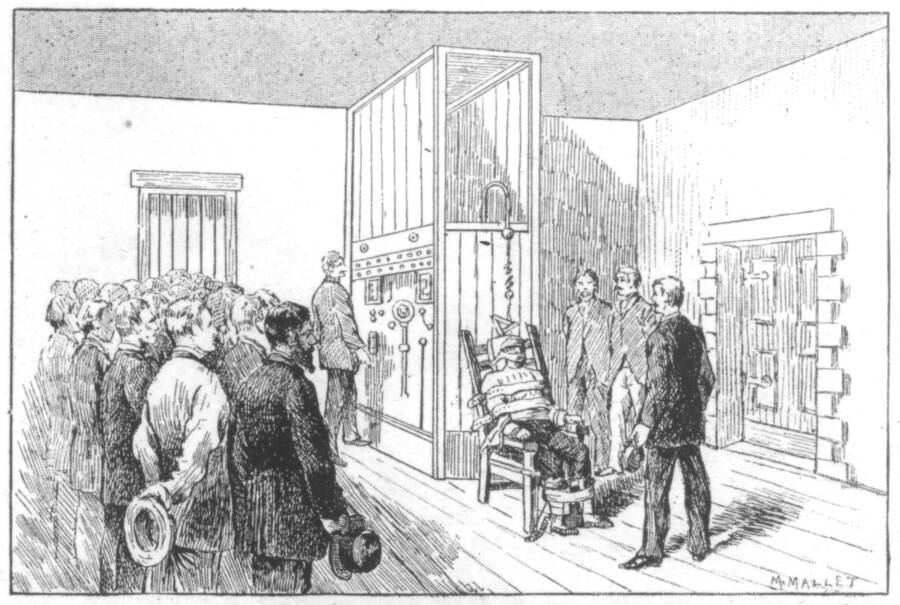

The Print Collector/Alamy Stock PhotoAnother depiction of William Kemmler’s execution by electric chair.

The witnesses to Kemmler’s execution by electric chair were “as miserable, as weak-kneed a lot of men as can be imagined,” The New York Times reported at the time. “They all seem to act as though they felt that they had taken part in a scene that would be told to the world as a public shame, a legal crime.”

The Chicago Tribune was even more scathing in its reporting of the execution. William Kemmler, the paper wrote, “was actually tortured to death with a refinement of cruelty that was unequalled in the dark ages.”

The Reaction To William Kemmler’s Death

Three hours after William Kemmler’s death, an autopsy suggested that he had fallen unconscious after the first electric shock and that he’d likely remained unconscious until he died. Thus, his death was seemingly more painless than it had appeared. The doctors also stated that Kemmler’s prolonged execution was either because the electrodes had not been properly placed or because there had been insufficient voltage or pressure.

The electric chair, in other words, was not the problem. They claimed that Kemmler’s botched execution had been due to human error.

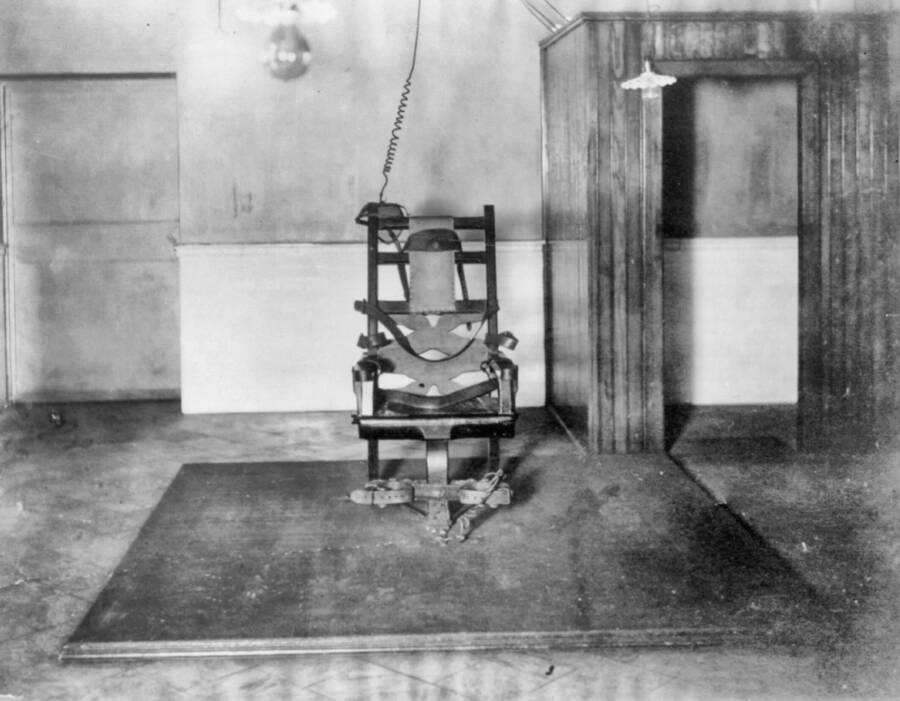

Niday Picture Library/Alamy Stock PhotoThe electric chair at Auburn State Prison. 1908.

Despite these findings, most people reacted with horror to Kemmler’s death. Some even called for the death penalty to be abolished entirely. Dr. George F. Shrady, editor of the Medical Record of New York and a witness to Kemmler’s execution, telegraphed an editorial to newspapers across the country.

“Although science has triumphed, the question of the humanity of the act is still an open one,” Shrady wrote. “We venture to predict that public opinion will soon banish the death chair, as it has done the rope, and imprisonment for life will be the only proper punishment meted out to a murderer…”

But Shrady was wrong: The electric chair continued to be used. On July 7, 1891, four men were electrocuted to death at a prison in New York. In 1899, the electric chair was used to execute a woman, Martha Place.

To date, more than 4,000 people have been executed in the electric chair. At its peak, 26 states used the electric chair as their preferred method of execution, though that number has fallen. Today, just one state — South Carolina — uses the electric chair as its primary means of execution. Eight other states — Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Tennessee — use it as an alternative. However, lethal injection, not the electric chair, has become the most standard method of execution in the United States.

As such, William Kemmler has been all but forgotten. The first man executed by electric chair was buried without ceremony in quicklime on the prison grounds. But those who witnessed his death never forgot what they saw.

“No one can depict in words the apparent horrible sufferings of that poor devil,” one witness said. “Everyone in the room lost their head. I would not think $1,000 an inducement for witnessing another electrocution.”

After reading about William Kemmler, discover the story of the breaking wheel, history’s most gruesome execution method. Or, go inside the grisly history of being hanged, drawn, and quartered.