Yigal Amir killed Yitzhak Rabin in November 1995 because he was opposed to Israel coming to a peace agreement with Palestine.

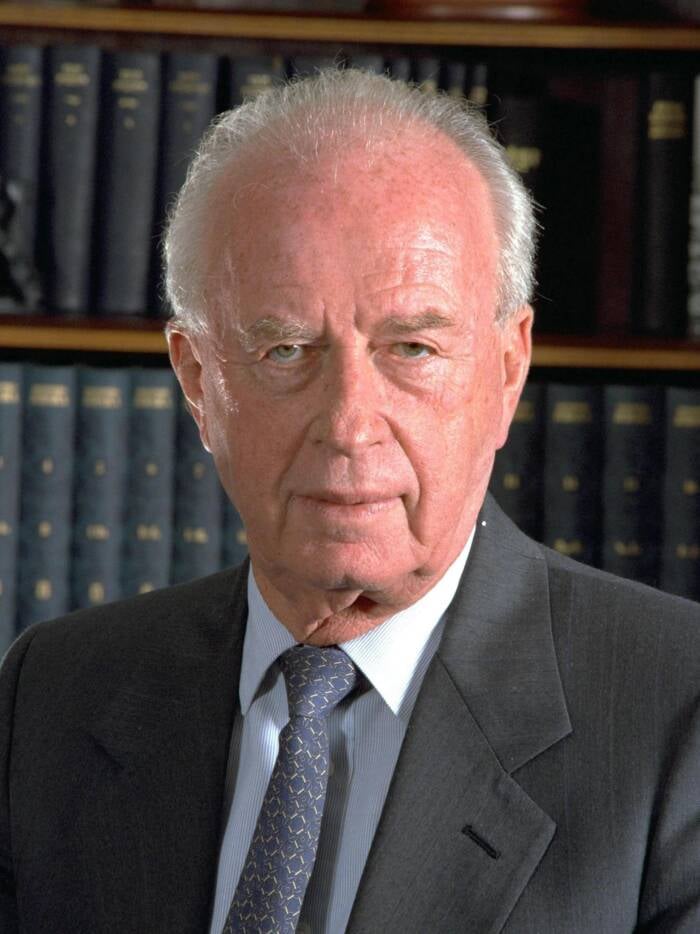

Israel Press and Photo Agency (I.P.P.A.)/Dan Hadani Collection, National Library of IsraelIsraeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin addressing the crowd in Tel Aviv’s Kings of Israel Square on Nov. 4, 1995.

The rally was ending. More than 100,000 people had gathered in Tel Aviv’s Kings of Israel Square on the evening of Nov. 4, 1995, their voices joining together as they sang songs of peace. The assassination of Yitzhak Rabin would soon shatter that sense of harmony.

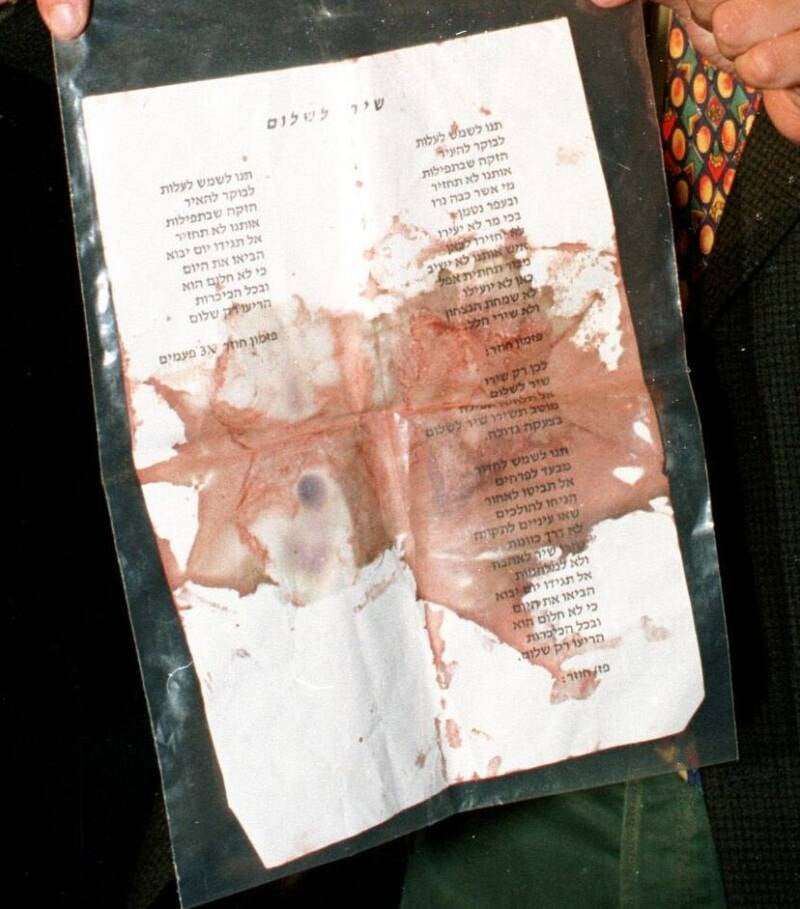

Prime Minister Rabin, a man who had spent his youth as a warrior, stood on stage swaying to the melody of “Shir LaShalom” — “A Song for Peace.” In his pocket, he carried the lyrics on a piece of paper that would soon become one of the most haunting relics of modern Israeli history.

Moments later, as Rabin descended the stairs toward his waiting car, three shots rang through the autumn night. The 73-year-old prime minister crumpled to the ground, mortally wounded not by an enemy soldier or a Palestinian militant, but by a fellow Israeli — a 25-year-old law student named Yigal Amir who believed he was saving his country by killing its leader.

Instead, Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination only further polarized Israeli politics and forced a reevaluation of peace talks with Palestine, the effects of which are still being felt 30 years later.

The Soldier Who Fought For Peace

National Photo Collection of IsraelMembers of the Israeli delegation to the 1949 Armistice Agreement talks: Commanders Yehoshafat Harkabi, Aryeh Simon, Yigael Yadin, and Yitzhak Rabin.

Born in Jerusalem in 1922 during the British Mandate, Rabin had grown up with the state of Israel itself. He was a product of the kibbutz movement, shaped by the ethos of practical Zionism and collective sacrifice. By age 26, he was commanding the Harel Brigade during Israel’s War of Independence. He then went on to serve in the Six-Day War of 1967 as the Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces.

Rabin was the quintessential Israeli general — tough, pragmatic, and seemingly unbreakable. His gravelly voice and blunt manner made him appear the antithesis of a visionary. Yet it was precisely this military credibility that would eventually give him the political capital to pursue what had once seemed impossible: genuine peace with Palestinians. Tragically, this also set the stage for the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin.

National Photo Collection of IsraelYitzhak Rabin believed peace should be achieved diplomatically, not through war.

“In the Arab-Israeli conflict, I don’t see a solution achievable by military means,” Rabin once said in a 1974 recording shared by The Jerusalem Post. “If there is any chance, it is only through political negotiation… But I’m exempt from addressing the issue, as we know the facts: no one is willing to talk to us about peace.”

But by the 1990s, Rabin’s tune was changing. Peace now seemed to be on the horizon, and his journey toward that goal began in earnest in 1992, when he returned to the prime minister’s office for his second term.

The First Intifada had dragged on for years, exhausting Israelis and Palestinians alike. Rabin, who had once ordered soldiers to break the bones of stone-throwing protesters, now saw the conflict’s futility with veteran eyes.

“You don’t make peace with friends,” he would famously say. “You make it with very unsavory enemies.”

The Oslo Accords Further Divide Israeli Politics

Public DomainYitzhak Rabin shaking hands with Yasser Arafat at the White House in 1993.

The Oslo Accords, signed on the White House lawn in September 1993, represented a seismic shift in Middle Eastern politics. The sight of Rabin shaking hands with Yasser Arafat, the longtime leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization, sent shock waves through Israel — shock waves that would set in motion the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin two years later.

During his remarks at the signing, as The New York Times reported at the time, Rabin had made his message of peace clear: “We who have fought against you, the Palestinians, we say to you today, in a loud and a clear voice: Enough of blood and tears! Enough!”

For his supporters, it was a courageous step toward ending decades of bloodshed. For his opponents, it was an unconscionable betrayal.

The Israeli right mobilized with unprecedented fury. Protests grew increasingly venomous. Demonstrators carried posters depicting Rabin in a Nazi SS uniform or dressed as Arafat.

At one particularly volatile rally, opposition leader Benjamin Netanyahu stood on a balcony overlooking a crowd burning pictures of the prime minister. The air crackled with apocalyptic rhetoric: Rabin was a traitor, a rodef (one who pursues another to kill them, whom Jewish law permits to be stopped by any means), a man trading Jewish blood for empty promises.

Religious nationalist rabbis issued statements questioning the Oslo process’s legitimacy. Some went further, invoking din rodef — an ancient concept that, in certain interpretations, could justify killing someone who endangered Jewish lives. While religious leaders stopped short of explicit calls for Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination, the atmosphere they created was electric with possibility.

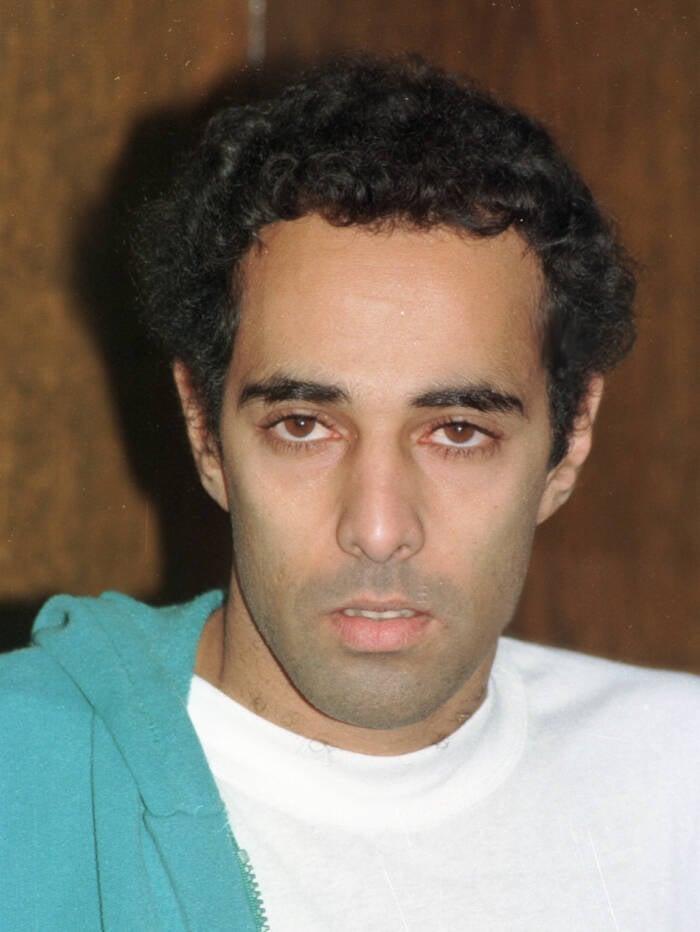

Gideon Markowiz, Israel Press and Photo Agency (I.P.P.A.)/Dan Hadani Collection, National Library of IsraelYigal Amir, Yitzhak Rabin’s assassin, in 1995.

Yigal Amir breathed this air deeply. A student at Bar-Ilan University, he was a product of the religious Zionist movement, a group that had traditionally combined devotion to both Jewish law and the Israeli state.

But Amir saw no contradiction between his faith and his plan to murder the prime minister.

In his mind, Rabin’s willingness to cede biblical territory to Palestinians constituted a mortal threat to Jewish lives. He believed he was acting in accordance with Jewish law, having consulted with rabbis and convinced himself that he had religious sanction for his deed. And so, on Nov. 4, 1995, Amir took action.

Three Shots In The Dark: The Assassination Of Yitzhak Rabin

Israel Press and Photo Agency (I.P.P.A.)/Dan Hadani Collection, National Library of IsraelThousands of supporters of the Oslo Accords gathered in Tel Aviv to hear Prime Minister Rabin speak on Nov. 4, 1995.

By 1995, security surrounding Rabin had grown lax. This was a product of both Israeli informality and a fatal miscalculation: the Shin Bet security service was focused on Palestinian threats, not Jewish ones.

Amir had stalked the prime minister for months leading up to the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, attending rallies and public events, probing for vulnerabilities. On the night of Nov. 4, he simply walked into the unsecured area where Rabin’s car was parked.

The peace rally had been a triumph. Rabin, who typically seemed uncomfortable with public displays of emotion, had been visibly moved by the crowd’s size and enthusiasm. In his final speech, he had spoken words that now echo with tragic irony:

“I have always believed that the majority of the people want peace and are ready to take risks for peace… Violence erodes the basis of Israeli democracy. It must be condemned and isolated. This is not the way of the State of Israel.”

Israel Press and Photo Agency (I.P.P.A.)/Dan Hadani Collection, National Library of IsraelThe bloodstained lyrics to “Shir LaShalom” that Rabin had in his pocket the night of his assassination.

As Rabin walked toward his waiting car following the rally, Amir approached from behind. He fired three shots, and two of them hit their mark. One bullet struck Rabin in the lower back, rupturing his spleen. The second ripped through his right lung. Rabin’s bodyguard, initially thinking firecrackers had gone off, realized too late what was happening.

By the time Rabin’s car reached Ichilov Hospital with Rabin bleeding in the back seat, the prime minister knew his wound was fatal. “It hurts,” he told his aide, “but it’s not terrible.”

Surgeons at the hospital worked frantically to save Rabin, but the damage was too extensive. At 11:10 p.m., Yitzhak Rabin was pronounced dead.

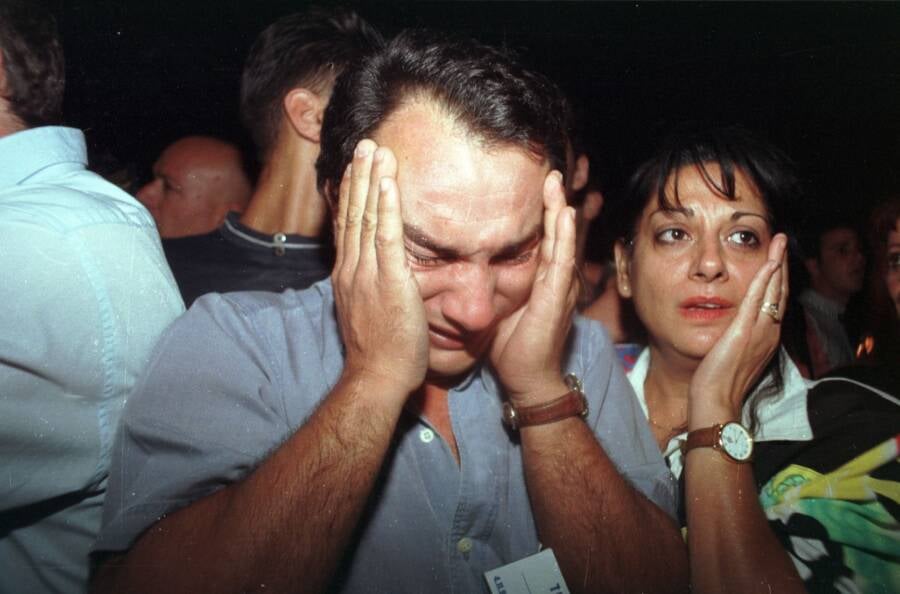

When President Ezer Weizman announced the news of the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin to the nation, many Israelis simply couldn’t process it. How could a man who had survived multiple wars be killed at a peace rally? How could the threat come not from outside, but from within?

The nation was in mourning — but not everyone was upset about Rabin’s death.

The Tumultuous Aftermath Of Yitzhak Rabin’s Assassination

Israel Press and Photo Agency (I.P.P.A.)/Dan Hadani Collection, National Library of IsraelPrime Minister Rabin’s supporters mourning his death shortly after it was announced.

Hundreds of thousands of people attended Rabin’s funeral, including Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, Jordan’s King Hussein, and U.S. President Bill Clinton, who delivered a heartbreaking eulogy in Hebrew: “Shalom, chaver” — “Goodbye, friend.”

King Hussein’s words cut even deeper. As recorded by the Yitzhak Rabin Center, the monarch solemnly stated, “You lived as a soldier, you died as a soldier for peace, and I believe it is time for all of us to come out, openly, and to speak our piece… We belong to the camp of peace. We believe in peace.”

For many Israelis, the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin represented a failure that transcended politics. The country had fought wars of survival against external enemies, but now it confronted an internal poison.

The Oslo peace process itself became a casualty of the assassination. Shimon Peres, who succeeded Rabin, lost the 1996 election to Netanyahu by less than one percentage point — a margin attributed partly to a wave of Hamas suicide bombings and partly to the political paralysis following Rabin’s death.

Yigal Amir, meanwhile, showed no remorse.

At his trial, he declared he had acted “for God, for the Torah of Israel, the people of Israel and the Land of Israel,” per the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. “I was forced to commit this act, [because] had I not, the damage to the people of Israel would have been irreversible.”

Amir received a life sentence plus six years, becoming a martyr to a small but significant fringe of Israeli society. Some religious nationalists visited him in prison. He eventually married, fathered a child through a conjugal visit, and continued to defend his actions.

Government Press Office/National Photo Collection of IsraelPrime Minister Rabin’s family at his funeral.

Nearly three decades later, the site of Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination — now renamed Rabin Square — remains a pilgrimage site for those who still believe in the possibility of peace. Every Nov. 4, thousands gather to remember what was lost that night. To many, Rabin was more than a leader — he was a path forward.

The peace process Rabin championed has long since collapsed. The optimism of the Oslo Accords has been replaced by walls, checkpoints, and intractable positions on both sides. The two-state solution that once seemed possible now feels even further out of reach.

The assassination of Yitzhak Rabin remains an eerie cautionary tale about the dangers of political incitement, the fragility of democratic norms, and the ease with which words can become violence.

After reading about Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination, learn about Harold Holt, the Australian prime minister who went for a swim and never came back. Or, read about the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and the Great Emancipator’s final days.